Study designs

Notes

Overview

The reporting of medical findings originally focussed on the description of individual patients with an unusual presentation.

This would be a novel or rarely used method of treatment, or an unexpected outcome. Some reports described several such cases treated by the same practitioner. The 20th century saw the development of larger scale studies that involved (for example) the collection of the views of individual patients, the inspection of patient medical records, following patients over time using standardised record keeping, or performing comparisons of patients receiving different treatments.

Recent years have seen the development of medical literature databases on the Internet, facilitating systematic reviews.

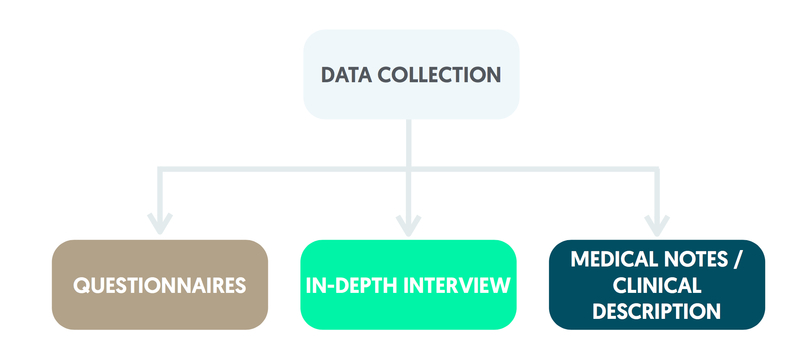

Data collection

Methods that are used in the collection of data include questionnaires, in-depth interviews, clinical measurements, medical notes and detailed clinical descriptions.

With most questionnaires, the focus is on closed questions that have a short list of responses. A single response may be requested although some questions allow two or more responses to be selected.

For a Likert scale, responses are ordered (e.g. strongly agree, agree, indifferent, disagree, strongly disagree). A visual analogue scale allows a patient to mark the point on a horizontal line that describes their level of pain where the left and right extremes of the line represent no pain and the highest level of pain imaginable respectively. Open questions, usually just a few at the end of a questionnaire, allow the patient to response in their own words.

Data from closed questions can be analysed by frequency counting, cross tabulation and statistical methods. Responses to open questions are listed and frequently made comments are highlighted.

Patient views can be explored in detail using in-depth interviews. A transcript of the discussion is created, which is analysed by looking for recurrent themes emerging from the interviews. In-depth interviews can take around an hour to conduct whereas a questionnaire might only take 5 or 10 minutes, so best use of staff time needs to be considered carefully at the planning stage. It is not necessarily true that questionnaires are better than interviews; the appropriate method needs to be selected. For studies that involve patient follow-up, a member of the research team may take routine clinical measurements. Medical notes are another useful source of information.

Types of study

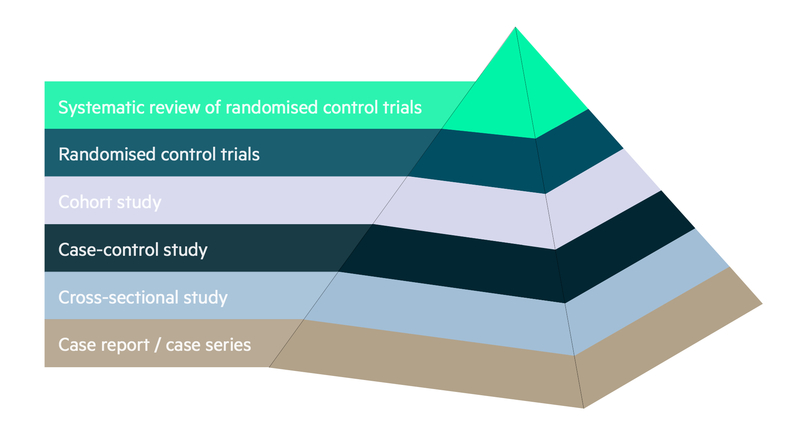

A number of study designs can be found within the medical literature. These can range from simple case reports and case series to more complex randomised controlled studies and systematic reviews. The relative merits of each study design are discussed below.

The consensus regarding the quality of the information that each study design is able to produce is summarised in the hierarchy of evidence diagram below:

Case report & case series

A case report consists of a description of an individual patient.

For published reports, the patient is generally unusual in terms of symptoms, signs, diagnosis, treatment, and/or outcome. For a case series, patients with a common characteristic such as diagnosis or method of treatment are identified from the clinic workload. Each patient is described although not in as much detail as for a case report. Information might be summarised using frequencies.

Case reports and case series cannot be generalised to other settings. However, this research can be conducted within the routine funding of the clinic.

Cross-sectional study

In a cross-sectional study, a sample of individuals is identified and information is collected often with participant completed questionnaires.

The complete sample can be summarised using basic methods of data presentation. Groups within the sample can be compared, e.g. males and females, and patterns identified. However, individual observations relate to a single time point only so it is not possible to explore cause and effect.

This type of study is commonly used for the provision of official statistics. In the United Kingdom, studies include the Health Survey for England and the Adult Dental Health Survey.

Case-control study

In a case-control study, a sample of individuals are identified and divided into those with a particular characteristic and those without it.

Information is collected from medical records and / or patient recollection. The two groups are then compared using the information obtained. For instance, a group of patients diagnosed with lung cancer might be compared with another group who do not have a lung cancer diagnosis.

Medical records and patient recollection are more likely to show a history of smoking in the lung cancer group, indicating a possible association. Although case-control studies are relatively inexpensive to conduct, both medical records and patient recollection can be incomplete or inaccurate.

Retrospective cohort study

For a retrospective cohort study, a sample of records of individuals is obtained from a data source.

These records are then followed to a point in the more recent past noting down the information available.

Prospective cohort study

In prospective cohort studies, a sample of individuals are recruited and followed up prospectively.

Information on individuals is obtained at the start of the study (sometimes called the baseline) and then collected at subsequent time points. At the completion of the study, individuals are compared in terms of their outcomes.

Prospective cohort studies can be expensive to conduct in terms of both money and staff time but the information collected over time can be used to demonstrate cause-and-effect relationships. For example, the British Doctors Study showed a link between tobacco smoking and a subsequent higher risk of lung cancer.

Prospective cohort studies are an important source of official statistics. Larger studies in the United Kingdom include the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, the National Child Development Study and the Whitehall studies of civil servants.

Randomised controlled trials

Randomised controlled trials are widely used to compare treatments, generally a new method relative to standard care.

In the simplest randomised design, a sample of individuals is obtained and each participant is independently allocated to either the new treatment or standard care based on the toss of a coin (head: new treatment; tail: standard care) creating the ‘treatment’ and ‘control’ groups.

Each participant receives the treatment allocated and is followed up. Once the study has been completed the groups are compared for differences in outcome.

Groups formed using randomisation are similar in terms of explanatory variables such as age, gender, baseline weight, baseline blood pressure, etc. The groups can be compared on a like-with-like basis.

If a randomised controlled trial incorporates double blinding, the medical staff and participating patients are unaware of the group to which they have been allocated. Withholding knowledge of the allocations from those involved in the study can considerably reduce measurement bias with subjective variables. Blinding is possible in a comparison of drugs if they can be administered as tablets with the same size, colour and taste. Blinding is not practical if the interventions are visibly different as in a comparison of two types of surgical procedure.

Randomised crossover trials

In randomised crossover trials, participants in the sample take each of two treatments (say A and B) in an order determined by randomisation.

After completion of the first treatment, an intervening (wash-out) period is used to minimise any residual treatment effects. Patients then receive the second treatment. Once all patients have received both A and B, the two treatments are compared on outcomes.

The benefit of the randomised crossover design is that the same patients receive both treatments. Randomised crossover trials are useful for investigating medical conditions such as chronic asthma for which both complete recovery and death are unlikely.

Some issues, such as smoking, should not be investigated using a randomised design, as it is clearly unethical to allocate individuals to either smoke or refrain from smoking tobacco. A more appropriate design would be a cohort study for which participants are simply observed.

Systematic review

A systematic (literature) review can be performed by a search of Internet databases (e.g. Cochrane library, EMBASE, and MEDLINE) with keywords relevant to the area of interest.

This produces a list of publications that the investigators can reduce down to those that they see as relevant. A technique known as meta-analysis can be employed to conduct an overall numerical evaluation of the findings.

Last updated: September 2017

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback