Mitral regurgitation

Notes

Overview

Mitral regurgitation refers to an incompetence of the valve that may occur due to abnormalities to the valve leaflets, subvalvular apparatus or left ventricle.

Regurgitation refers to a ‘leaking’ of blood through the valve during ventricular systole. It can be classified as primary or secondary:

- Primary: refers to pathology affecting components of the valve itself. Degenerative disease is the most common cause.

- Secondary: refers to regurgitation as a result of changes to left ventricular geometry. This results in distortion of the subvalvular apparatus and valve leaflets. Dilated and ischaemic cardiomyopathies are the most common cause.

It may also be classified into acute and chronic disease based on the speed of onset and severity of regurgitation. Mitral regurgitation is the second most common indication for valvular surgery (the most common being aortic stenosis).

Anatomy

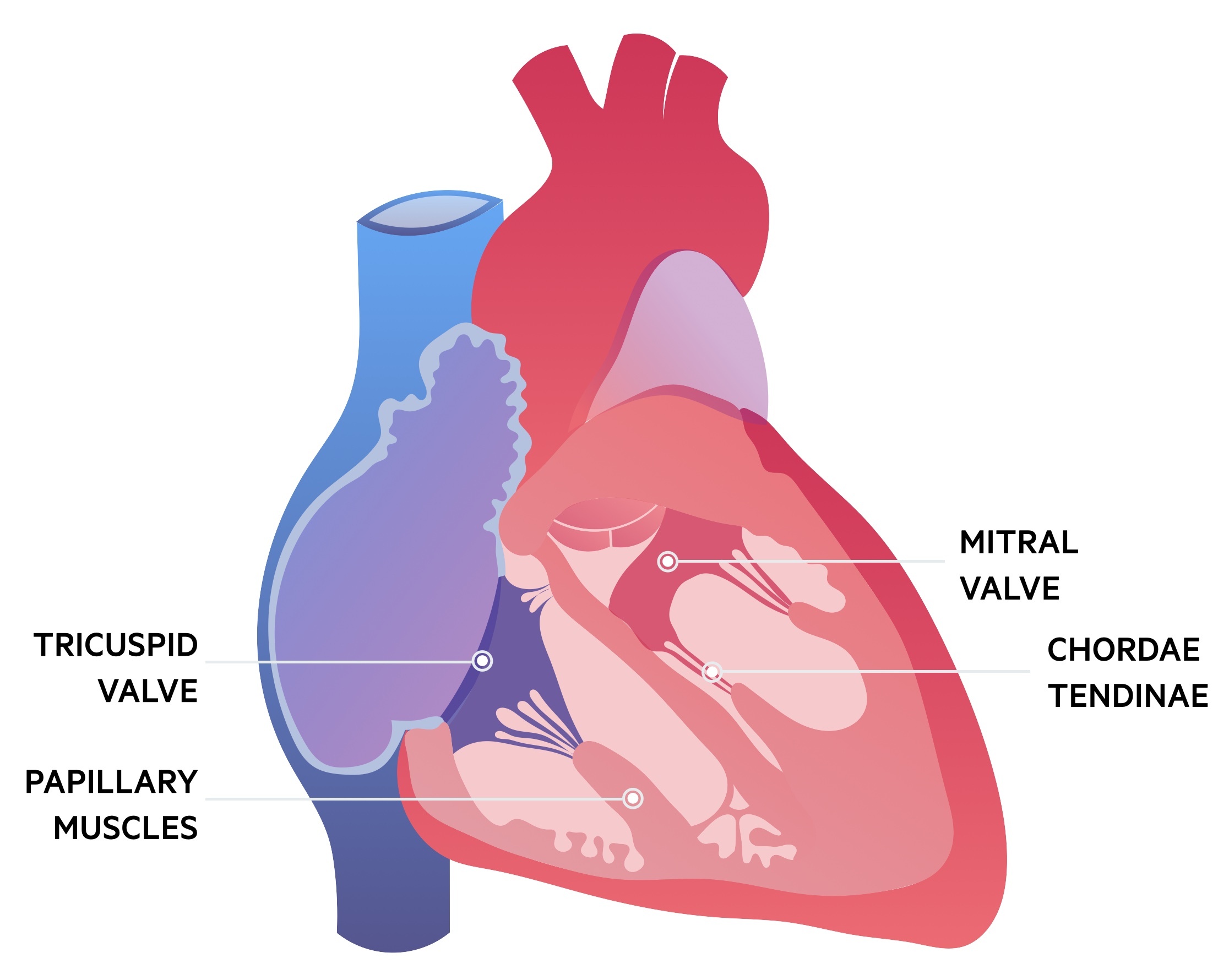

The mitral valve is termed (somewhat erroneously) a bicuspid valve and sits between the left atrium and ventricle.

The term atrioventricular valve complex refers to the entirety of the valve and its supporting apparatus. It consists of the orifice, valve leaflets, chordae tendineae, papillary muscles and the ventricle itself.

There are two valve leaflets, anterior and posterior. The posterior leaflet is divided by indentations into three scallops (P1, P2, P3). The corresponding areas on the anterior leaflet may also be divided to reflect the posterior scallops (A1, A2, A3). The normal cross-sectional area of the mitral valve orifice is 4-6 cm2.

Each leaflet is attached to chordae tendineae, which are string-like structures that connect leaflets to papillary muscles. Two papillary muscles support the mitral valve and arise from the ventricular wall.

Pathology affecting any of these structures may lead to valvular dysfunction. In normal physiology the mitral valve opens to allow left ventricular filling and closes during ventricular contraction.

Aetiology

The cause of MR may be divided into acute and chronic cases.

Chronic MR

Trivial MR is a relatively common finding on echocardiogram. In those with more significant incompetence heart failure can result and surgical intervention may be needed.

Primary MR: degenerative valve disease is the most common cause. Other causes include:

- Infective endocarditis

- Rheumatic heart disease

- Congenital anomalies

- Medications (e.g. ergotamine, bromocriptine, pergolide)

Secondary MR: ischaemic MR may result in chronic MR following a myocardial infarction (more commonly than acute ischaemic MR). The ischaemic insult leads to left ventriclar remodelling and dysfunction impairing the valves ability to close. Other causes include cardiomyopathy (dilated and hypertrophic).

Acute MR

Acute disease typically results from primary forms of MR. It can occur following myocardial ischaemia/infarction with secondary papillary muscle rupture and valvular incompetence.

Non-ischaemic forms include ruptured chordae tendineae and valvular disease secondary to infective endocarditis and rheumatic heart disease.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of acute and chronic MR differ as in chronic disease compensatory mechanisms have time to develop.

Chronic MR

MR results in a backflow of blood during ventricular systole from the left ventricle into the left atrium. This reduces the ejection fraction as part is flowing backwards and raises the atrial pressure.

In chronic MR there is gradual worsening of the regurgitant fraction that initially allows for compensatory mechanisms to occur. Eventually failure may result and the patient enters a decompensated state:

- Compensated state: in the setting of mitral regurgitation the left ventricle and atrium dilate. The compliant and dilated left ventricle undergoes eccentric hypertrophy and is able to maintain a larger stroke volume and as such ejection fraction. The compliant and dilated left atrium prevents rises in atrial and therefore pulmonary pressures.

- Decompensated state: eventually such changes cannot maintain normal cardiac function and the remodelling becomes increasingly pathological. The heart fails, ejection fraction falls and pulmonary pressures rise.

Acute MR

In acute MR there are fast and significant changes to flow without time for any adaptation or remodelling to occur as is seen in chronic MR.

The new regurgitation causes increased pressure within a non-compliant left atrium. As result of the lack of compliance this is reflected in rises in pressure in the pulmonary circulation. This pulmonary hypertension may cause pulmonary oedema to develop.

The ejection fraction falls precipitously as blood is ejected back across the regurgitant valve instead of forward though the aortic valve. A tachycardic response may be raised to help compensate for the reduced ejection fraction in an attempt to return the cardiac output to normal. This is rarely sufficient and cardiogenic shock can occur.

Clinical features

The clinical features of MR include the signs and symptoms of heart failure and a pansystolic murmur.

Acute vs Chronic

Acute MR: characterised by the rapid development of heart failure with inadequate cardiac output and flash pulmonary oedema. Patients may be shocked and breathless, the condition is potentially life-threatening, and can necessitate emergency surgery.

Chronic MR: may be asymptomatic for many years until heart failure results in symptoms developing. Symptoms tend to involve dyspnoea and orthopnoea that results from pulmonary hypertension. Fatigue and malaise are common. As right-sided heart failure develops patients may notice swelling of their ankles (peripheral oedema).

Signs of MR

- Palpation: the apex beat may be displaced laterally. A systolic thrill may be felt in severe disease.

- Murmur: a pansystolic murmur is characteristic.

- Heart sounds: S1 (first heart sound) may be soft due to incomplete closure. An additional heart sound, S3, may be heard caused by rapid filling of a dilated ventricle.

- Signs of heart failure: auscultation may note bi-basal crackles and examination demonstrate peripheral oedema.

Investigations

Echocardiogram allows for the confirmation of an incompetent valve, assessment of the severity and identification the underlying cause.

CXR

In chronic MR evidence of left atrial and ventricular enlargement is often seen. In acute MR cardiomegaly is normally absent (unless there was pre-existing pathology) and signs of pulmonary oedema are seen. On the CXR left atrial enlargement can be seen with the tell-tale sign of a 'double right heart border' cause by the large left atrium.

Dilated left atrium and left ventricle in a patient with chronic MR

Image courtesy of Dr Vincent Tatco, Radiopaedia

ECG

In acute MR the ECG may be entirely normal or reflect a recent myocardial infarction. In chronic MR changes can include p-mitrale - a broad, notched p-wave with a negative component in V1 - (reflecting left atrial enlargement) and signs of left ventricular hypertrophy. Arrhythmia's, most commonly atrial fibrillation, are sometimes present.

Echocardiogram

Echo is the diagnostic modality of choice. Allows visualisation of the incompetent valve and can confirm the underlying aetiology. Left atrial and ventricular enlargement may be seen in chronic MR.

Other

A number of additional investigations may be ordered depending on the clinical context.

- Exercise testing: cardiopulmonary exercise testing may be used to assess a patients overall functional capacity. Exercise echocardiography is used to demonstrate changes in MR during exercise.

- Cardiac MRI: may be used when echocardiogram is inadequate.

- Cardiac catheterisation: an invasive investigation typically used for evaluation of the coronary vessels prior to valvular surgery. Right sided catheterisation can be used to confirm pulmonary hypertension.

Managing primary MR

Primary MR may be managed with medical therapies or surgical intervention.

Acute MR

Patients with acute MR are normally profoundly unwell - the condition characterised by shock and flash pulmonary oedema. Management follows two stages:

- Medical stabilisation: The aim is to stabilise the patient and allow for pre-operative optimisation. Sodium nitroprusside can be used to reduce afterload and thereby reduce MR. Patients with hypotension may require inotropic agents and an intra-aortic balloon pump.

- Surgery: Timing of surgery depends on the patients clinical state and the underlying aetiology. In infective endocarditis and chordal rupture, repair is generally preferred. When secondary to papillary muscle rupture, replacement is typically required.

Chronic MR

- Medical therapy: In patients with chronic MR and heart failure, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers and spironolactone may all be considered. Cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) is used when appropriate.

- Surgical therapy: Surgery is considered in symptomatic patients with a LVEF > 30%. It is also considered in other patients (both symptomatic and asymptomatic) based on a complicated set of criteria. Other surgical measures include ventricular assist devices, cardiac restraint devices and heart transplantation.

Managing secondary MR

In secondary MR there is less conclusive evidence showing improved survival following mitral valve intervention.

Secondary MR is associated with increased mortality though at present there is less evidence showing surgical intervention improves outcomes. The management should be guided by MDT with key input from both heart failure and electrophysiology specialists. Medical therapy should follow heart failure management. CRT should be considered when appropriate.

The indications for surgery are complex and in some cases have a relatively limited evidence base. In patients undergoing CABG with LVEF > 30% with severe secondary MR, it should be considered. It is also discussed with patients with ongoing symptoms despite optimal medical therapy (including CRT if indicated).

Last updated: June 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback