Pulmonary stenosis

Notes

Overview

Pulmonary stenosis occurs when there is narrowing of the pulmonary valve or the area just above or below it.

Pulmonary stenosis refers to narrowing around the area of the pulmonary valve, which leads to restriction of blood flow from the right ventricle of the heart to the pulmonary artery.

Typically, pulmonary stenosis may be:

- Congenital (i.e. present from birth), OR

- Adult-onset.

It is vital to differentiate severe and critical cogenital pulmonary stenosis from mild-to-moderate. This is because severe and critical congenital pulmonary stenosis is an acute onset, life-threatening condition which usually presents in the neonatal period. Due to the quite marked differences in presentation, investigation, and management, we will discuss severe and critical cogenital separately to mild-to-moderate congenital and adult-onset.

Epidemiology

Approximately 95% of cases of pulmonary stenosis are congenital.

Pulmonary stenosis is primarily a paediatric condition, since 95% of cases are congenital. It occurs in ~1 in 1500 live births.

Aetiology

The cause of pulmonary stenosis may be congenital or acquired.

Congenital

These account for approximately 95% of cases:

- Sporadic: Most cases of congenital PS are sporadic i.e. not caused by a known genetic defect.

- Congenital syndrome: A minority of cases will present as part of congenital syndrome (e.g. Noonan Syndrome).

Acquired

These account for approximately 5% of cases:

- Carcinoid heart disease* (the most common acquired cause of PS).

- Rheumatic heart disease

- Infective endocarditis

* Carcinoid syndrome involves the release of vasoactive substances from a tumour (usually of the gastrointestinal tract). It is possible that serotonin release from such a tumour leads to fibrous changes of the pulmonary valve, leading to regurgitation, stenosis, or both).

Pathophysiology

Most patients with mild-to-moderate congenital pulmonary stenosis or adult-onset will remain asymptomatic.

Most patients with mild-to-moderate congenital pulmonary stenosis or adult-onset will remain asymptomatic. For example, one study found that 96% of patients required no interventions for their PS after a 10 year follow up. However, in severe and critical pulmonary stenosis, the presentation is usually acute, life-threatening, and in the early neonatal period.

Here, we will discuss both presentations of pulmonary stenosis separately.

Severe and critical congenital pulmonary stenosis

The majority of patients with pulmonary stenosis are born with a tricuspid valve. In other words, a valve with the normal number of leaflets. However, the leaflets are more fibrosed, thickened or fused.

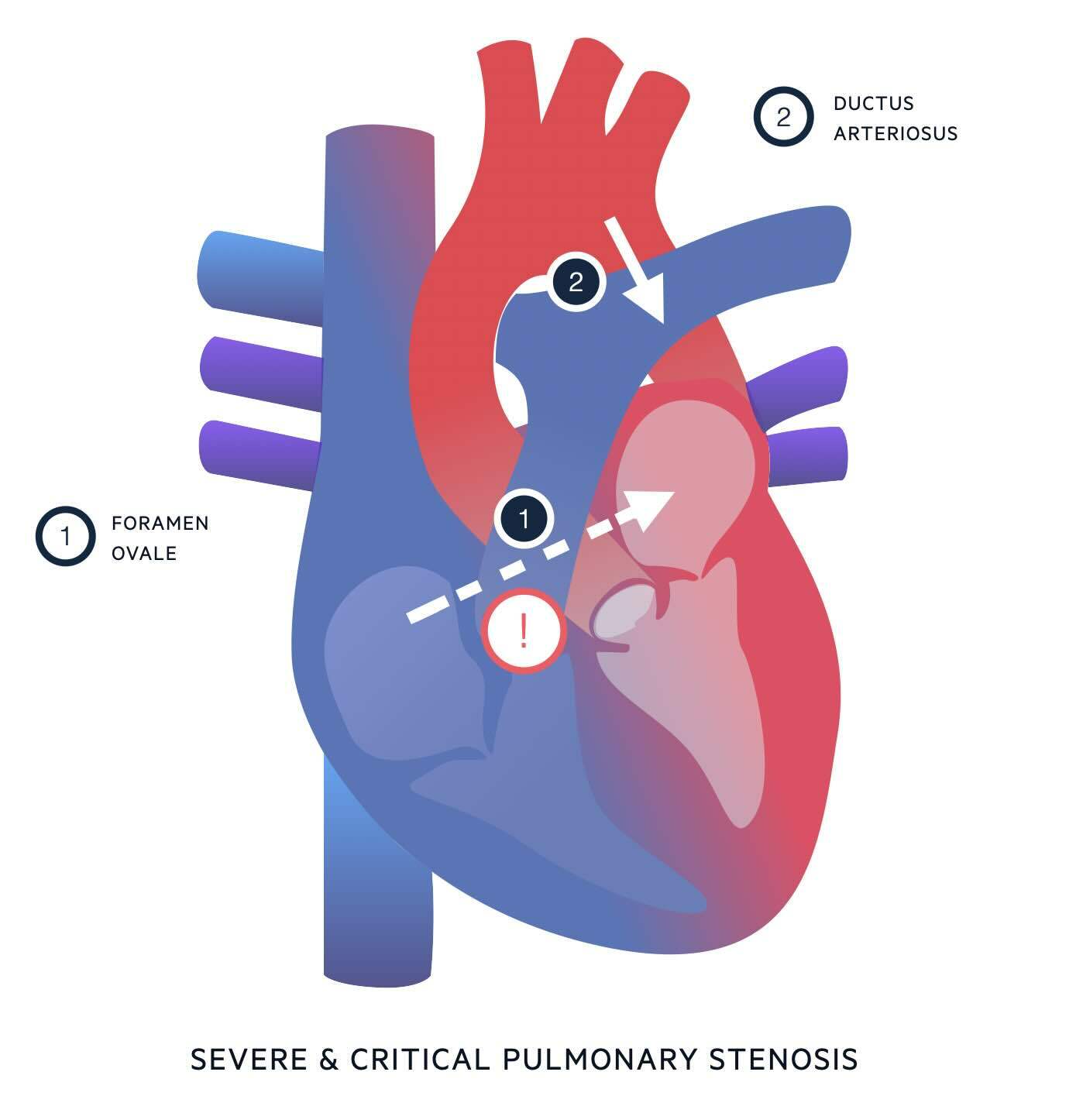

Understanding the anatomy of pulmonary stenosis will help you understand the clinical features and treatment. In severe and critical PS, outflow from the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery is severely impaired. In the absence of an atrial septal defect or ventricular septal defect, there are only two ways blood can move from the right side of the heart to the left; via the foramen ovale or a patent ductus arteriosus.

- Via the foramen ovale.

- The foramen ovale is an opening between the atria which – in the foetal circulation - allows blood to move from right atrium to left atrium, bypassing the lungs.

- The foramen ovale usually undergoes functional closure in minutes to hours after birth, and subsequent permanent fusion over time.

- In severe and critical PS, if a degree of tricuspid regurgitation is present, some blood may be able to flow backwards from the right ventricle into the right atrium.

- This will raise the right atrial pressure, leading to a right to left shunt through the foramen ovale.

- This right to left shunt may help keep the foramen ovale open.

- Right to left blood flow through the foramen ovale is useful for allowing mixing of blood from the right and left sides of the heart, but does not contribute to pulmonary blood flow.

- Via the ductus arteriosus.

- The ductus arteriosus is a vascular connection between the pulmonary artery and the distal arch of the aorta.

- In the foetal circulation, it allows blood being pumped out of the right ventricle to bypass the high-resistance circulation of the foetal lungs, by taking a shortcut from the pulmonary artery to the aorta.

- The ductus arteriosus usually closes within 24 hours after birth, partly due to reduced prostaglandin production.

- In severe and critical PS, the ductus arteriosus is the only way for blood to be pumped around the pulmonary circulation. In this case, the flow of blood through the ductus is reversed from what is normal in the foetal circulation i.e. blood flows from the aorta into the pulmonary artery and around the lungs.

Mild-to-moderate congenital and adult-onset pulmonary stenosis

Initially, infants and children with mild and moderate PS are asymptomatic. Most patients will remain asymptomatic. For example, one study found that 96% of patients required no interventions for their PS after a 10 year follow up.

In a minority of patients, the pulmonary valve undergoes gradual fibrous thickening (+/- calcification). As this fibrosis progresses, the valve becomes stiffer, meaning the degree of pulmonary stenosis becomes more severe.

This results in 3 issues:

- Reduced blood flow into the pulmonary artery: To begin with, blood flow to the lungs via the stenotic valve may be adequate at rest, and it may only be during exertion – when patients need to increase their pulmonary blood flow – that the stenosis becomes limiting. With time, the stenosis may limit blood flow at rest.

- Right ventricle has to work harder: this is to pump blood through the stenotic pulmonary valve. As a result, the right ventricle hypertrophies to cope with the increased work. Eventually this leads to right ventricular dysfunction and right-sided heart failure.

- Increased end-diastolic volume and pressue: Since the right ventricle ejects less blood during systole, more blood will be left in the right ventricle at the start of diastole. This increased end-diastolic volume (and therefore increased right ventricular end-diastolic pressure) resists ventricular filling from the right atrium during diastole. This leads to blood being diverted backwards via the vena cava.

Clinical features

Severe and critical congenital pulmonary stenosis usually presents in the early neonatal period.

Severe and critical congenital pulmonary stenosis

The presentation of pulmonary stenosis in the neonatal period is mainly explained by the right-to-left shunt through the foramen ovale.

This allows deoxygenated blood to enter the systemic circulation, leading to:

- Low peripheral oxygen saturations

- Cyanosis

Due to the cyanosis, this is considered a medical emergency. Resuscitation is appropriate either before – or in parallel to – diagnostic workup. Neonatal resuscitation is beyond the scope of this topic, but generally follows an ABCDE approach.

The key part of the acute management in severe and critical pulmonary stenosis is starting prostaglandins:

- We saw in Pathophysiology that blood flow through the pulmonary circulation relies entirely on the patent ductus arteriosus. This is why critical PS is also known as a “duct-dependent congenital heart defect”.

- It is therefore imperative that we keep the ductus arteriosus open.

- An infusion of prostaglandins (PGE1) will achieve this.

Mild-to-moderate congenital pulmonary stenosis and adult-onset

The typical features on history include:

- Exertional dyspnoea (due to an inability to increase pulmonary blood flow in response to exercise)

- Chest pain

- Fatigue

- Painful hepatomegaly (due to right heart failure)

Note that mild pulmonary stenosis causes no symptoms. If a patient with mild pulmonary stenosis presents with symptoms of right-heart failure, you should look for other causes for their symptoms.

On examination, typical findings of pulmonary stenosis include:

- Parasternal heave (if right ventricular hypertrophy is present)

- Palpable thrill (i.e. a palpable reflection of the murmur, usually felt over pulmonary area)

- Murmur: typically ejection systolic, loudest in pulmonary area (second intercostal space, left sternal edge), loudest on inspiration ('RILE')

- Prominent A-waves: seen in the jugular venous pressure (JVP)

- Features of right-sided heart failure: raised JVP, peripheral oedema, hepatomegaly

Investigations & diagnosis

Echocardiography is the main diagnostic tool.

Echocardiography is the main diagnostic tool for pulmonary stenosis; it can both diagnose and grade pulmonary stenosis (see ‘Classification’ below). This is for both neonates with critical pulmonary stenosis and in mild-to-moderate or adult-onset cases.

Patients may undergo other tests during their workup, such as chest x-ray and ECG. The following results on these tests might point towards PS:

- Chest x-ray: Enlarged right atrium and/or ventricle.

- Electrocariogram (ECG): Features of right ventricular hypertrophy e.g. right axis deviation, P-pulmonale

Classification

Grading pulmonary stenosis is based on the echocardiography.

On echocardiography, the estimated pressure gradient across the pulmonary valve is used to determine the grade. This differentiates the severity of pulmonary stenosis into mild, moderate, or severe.

- MILD: < 40 mmHg

- MODERATE: 40-60 mmHg

- SEVERE: > 60 mmHg

NOTE: Different guidelines use different cut-off values for each category, but most sources quote values close to these.

Management

Neonates with severe or critical PS require urgent intervention.

Severe and critical congenital pulmonary stenosis

Any neonate with suspected severe or critical pulmonary stenosis requires urgent resuscitation, which should included starting a prostaglandin infusion to maintain a patent ductus arteriosus.

Once stable, patients will undergo surgical intervention.

The exact type of surgery depends on the morphology of each patient’s pulmonary stenosis:

- Balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty: More common. In this procedure, the native pulmonary valve is dilated using a balloon.

- Surgical valvotomy.

The long-term prognosis for patients who undergo both balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty and surgical valvotomy is excellent.

Mild-to-moderate congenital and adult-onsent pulmonary stenosis

The management depends on the severity of stenosis and whether patients are symptomatic or asymptomatic.

- MILD: Cardiology follow-up with ECHO and ECG every 5 years

- MODERATE: Regular cardiology follow-up unless symptomatic in which case intervention may be considered. Balloon valvuloplasty preferred. In asymptomatic patients, the need for intervention is less conclusive.

- SEVERE: Invasive treatment generally recommended regardless of symptoms. Balloon valvuloplasty preferred.

Patients with mild pulmonary stenosis may never require intervention, and have a normal life expectancy. Patients who undergo balloon valvotomy tend to do well. After reopening the valve, the pressure across it reduces over several months. With more time (i.e. months to years) right ventricular hypertrophy may start to reverse.

Last updated: September 2024

References:

-

UpToDate. Pulmonic stenosis in infants and children: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis

-

UpToDate. Pulmonic stenosis in infants and children: Management and outcome.

-

UpToDate. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of pulmonic stenosis.

-

Sharma, R. et al. Pulmonary valve stenosis. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 17 May 2024) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-57547

-

Morgan M, et al. Patent foramen ovale. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 17 May 2024) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-31984

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback