Acromegaly

Notes

Overview

Acromegaly is a condition caused by an excess of growth hormone (GH) most commonly related to a pituitary adenoma.

It tends to present with macrognathia, frontal bossing and enlargement of hands and feet. Presentation may also be related to the aetiology - e.g. mass effect of a pituitary adenoma resulting in visual field defects and headache. It is associated with a number of systemic conditions (e.g. cardiovascular disease, diabetes).

The condition is thought to be rare though the true prevalence is hard to establish. Recent studies estimate a prevalence of up to 1 in 1000 individuals in patients who were randomly screened.

Diagnosis is made with IGF-1 measurements, oral glucose tolerance test and imaging of the pituitary. Treatment may be with surgery, radiotherapy or pharmacological management.

NOTE: Gigantism is a related condition that occurs in childhood due to GH excess prior to epiphyseal fusion - it is very rare. Untreated patients have rapid growth and very tall adult stature.

Physiology

Growth hormone, also termed somatotropin, is a peptide hormone that is produced and released by somatotropic cells within the anterior pituitary.

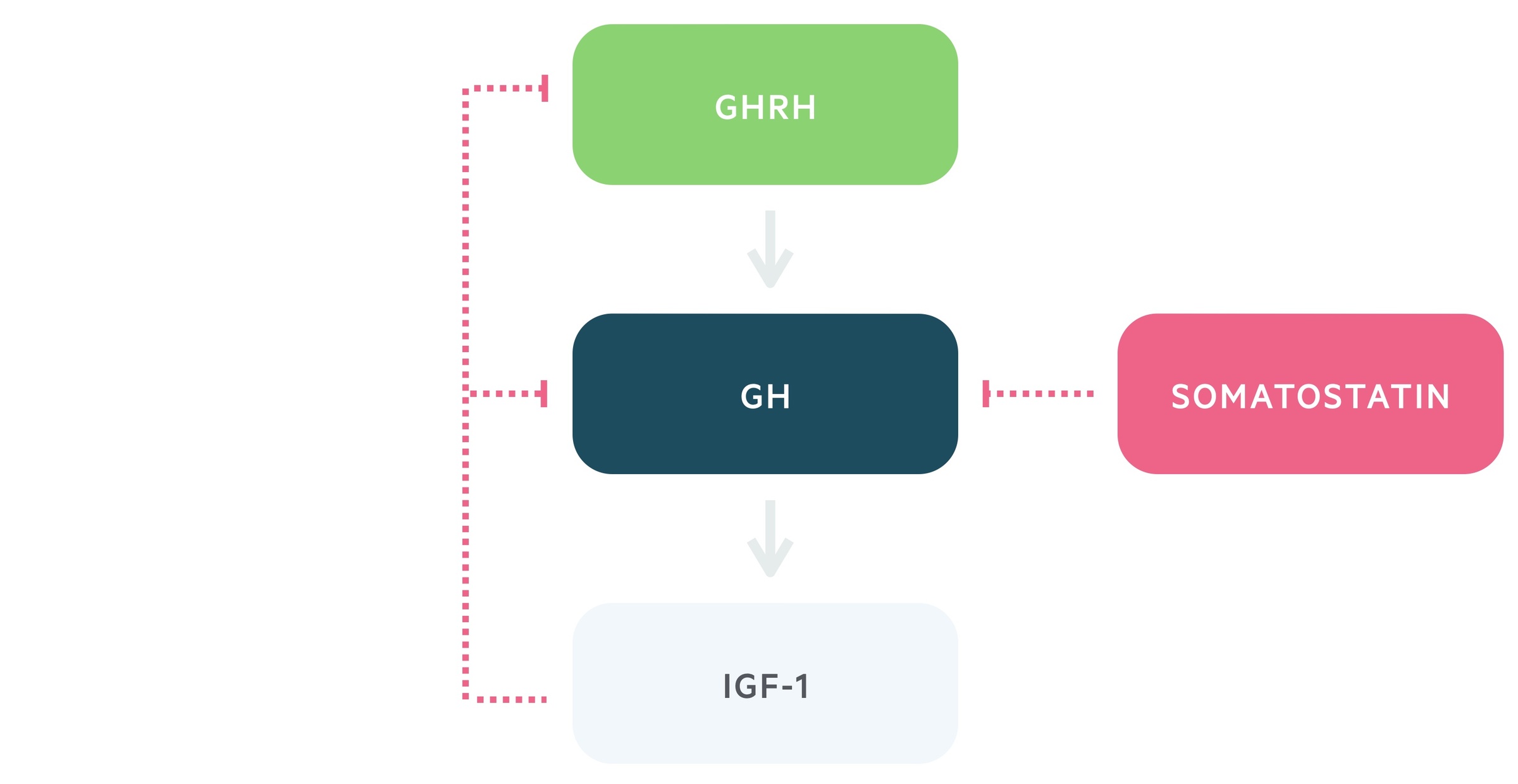

1. Growth hormone releasing hormone

Growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH) is released from the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus.

It is transported via the hypophyseal portal system to the anterior pituitary. Here it stimulates the release of growth hormone.

2. Growth hormone

Growth hormone (GH) is released from the somatotropic cells of the anterior pituitary in response to GHRH.

It stimulates the release of insulin-like growth factor -1 (IGF-1). Growth hormone exhibits pulsatile secretion and levels may vary widely during the day. In general, IGF-1 has steadier levels.

3. Insulin-like growth factor -1

IGF-1 is produced and released by the liver. It has widespread growth promoting effects.

This axis features negative feedback, in which IGF-1 and GH release leads to the inhibition of GHRH and stimulation of somatostatin release. Somatostatin is a negative regulator of growth hormone secretion.

Aetiology

Pituitary adenomas account for > 90% of cases of acromegaly.

Pituitary Adenoma

Growth hormone secreting somatotroph adenomas are the commonest cause of acromegaly. When this occurs in childhood prior to fusion of the epiphyseal growth plates pituitary gigantism is seen.

Other (rare)

Other causes of acromegaly are very rare. They are related to excess secretion of GHRH or GH:

- Ectopic release of GH: May be seen in neuroendocrine tumours.

- Ectopic release of GHRH: Related to tumours including carcinoid and small cell lung cancer.

- Excess hypothalamic release of GHRH: Related to hypothalamic tumours.

Clinical features

Acromegaly typically has an insidious onset and is often diagnosed late.

Clinical features may be related to:

- Excess growth hormone secretion

- Mass effects of a pituitary adenoma

Rarely features will reflect the less common causes of acromegaly such as carcinoid and lung cancer.

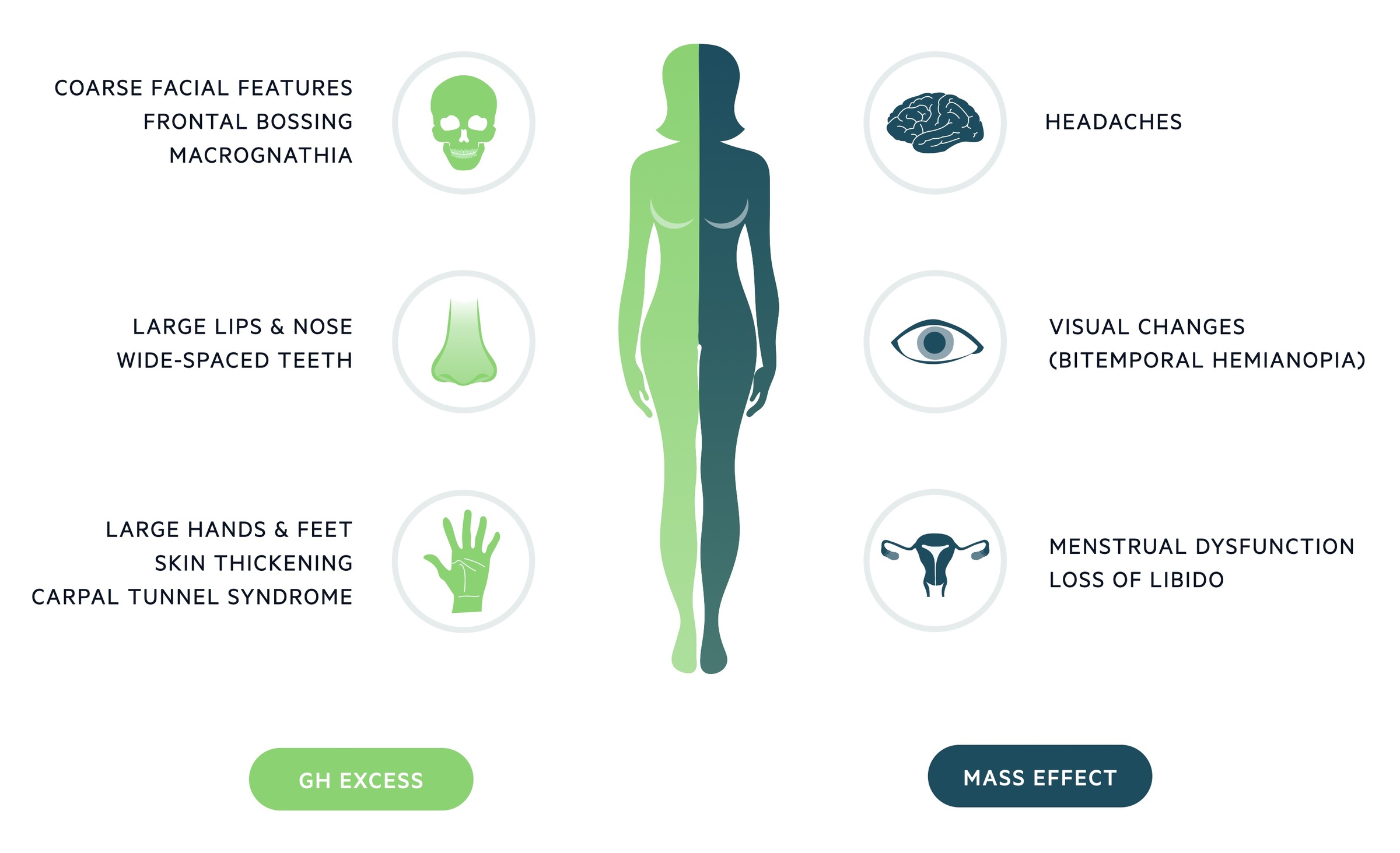

Growth hormone excess

Acromegaly leads to enlargement of hands, feet, lips and nose. Examination should look for wide spaced teeth, prognathism and frontal bossing. Men may note a deepening of their voice and some patients develop carpal tunnel syndrome.

As the condition, by definition, occurs following fusion of the epiphyseal growth plates, the strikingly tall stature that characterises gigantism is not seen.

GH and IGF-1 excess has systemic effects leading to a increased risk of a number of conditions:

- Cardiovascular disease: There is an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and its complications. This includes hypertension, cardiomyopathy, left ventricular hypertrophy and heart failure.

- Insulin resistance: Acromegaly results in increased insulin resistance and a risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

- Obstructive sleep apnea: There is an increased incidence of OSA in those with acromegaly.

- Organomegaly: There may be enlargement of visceral organs including the liver, kidneys, heart, prostate and lungs.

- Colonic pathology: There appears to be an increased risk of colorectal cancer and diverticulosis.

- Thyroid gland: Enlargement of the thyroid gland is common and may be either a diffuse enlargement or multinodular in nature. There may be an increased incidence of thyroid cancer.

- Headache: This may be related to mass effect from a pituitary adenoma or as a result of GH excess itself.

Mass effects

Macroadenomas may result in mass effects. Headaches are commonly seen. Mass effects may also result in visual changes and abnormal pituitary function.

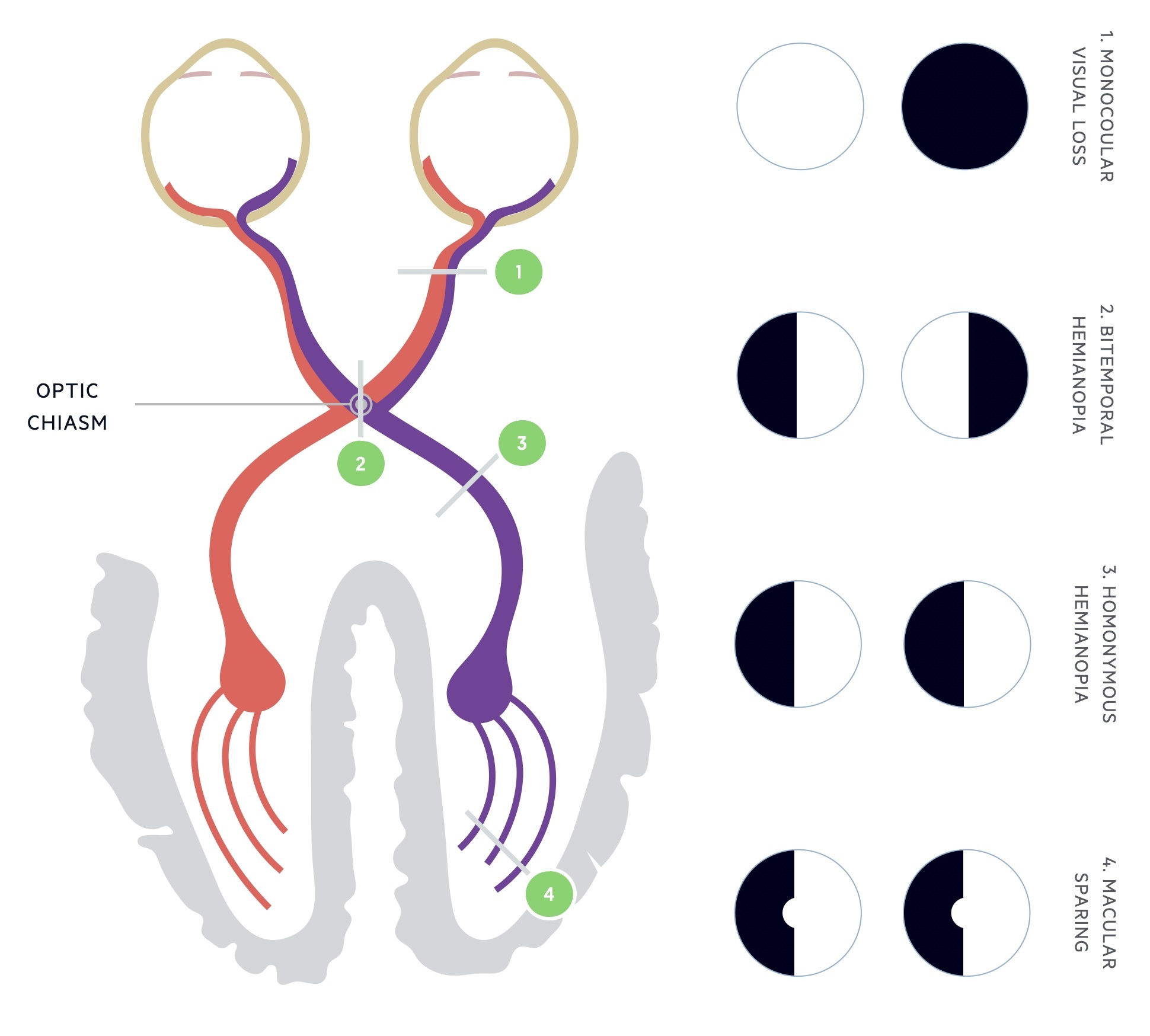

Visual loss: Visual changes develop in up to 10% of patients. Suprasellar extension of a macroadenoma can lead to direct pressure on the optic chiasm. The defect is classically bitemporal hemianopia.

Pituitary function: A macroadenoma may impair the ability of the rest of the pituitary to function. In women menstrual dysfunction is seen, whilst men can be affected by erectile dysfunction. In up to 30% of patients concomitant hyperprolactinaemia is seen. Features of hyperprolactinaemia include galactorrhea, dysmenorrhoea, hypogonadism and infertility.

Diagnosis

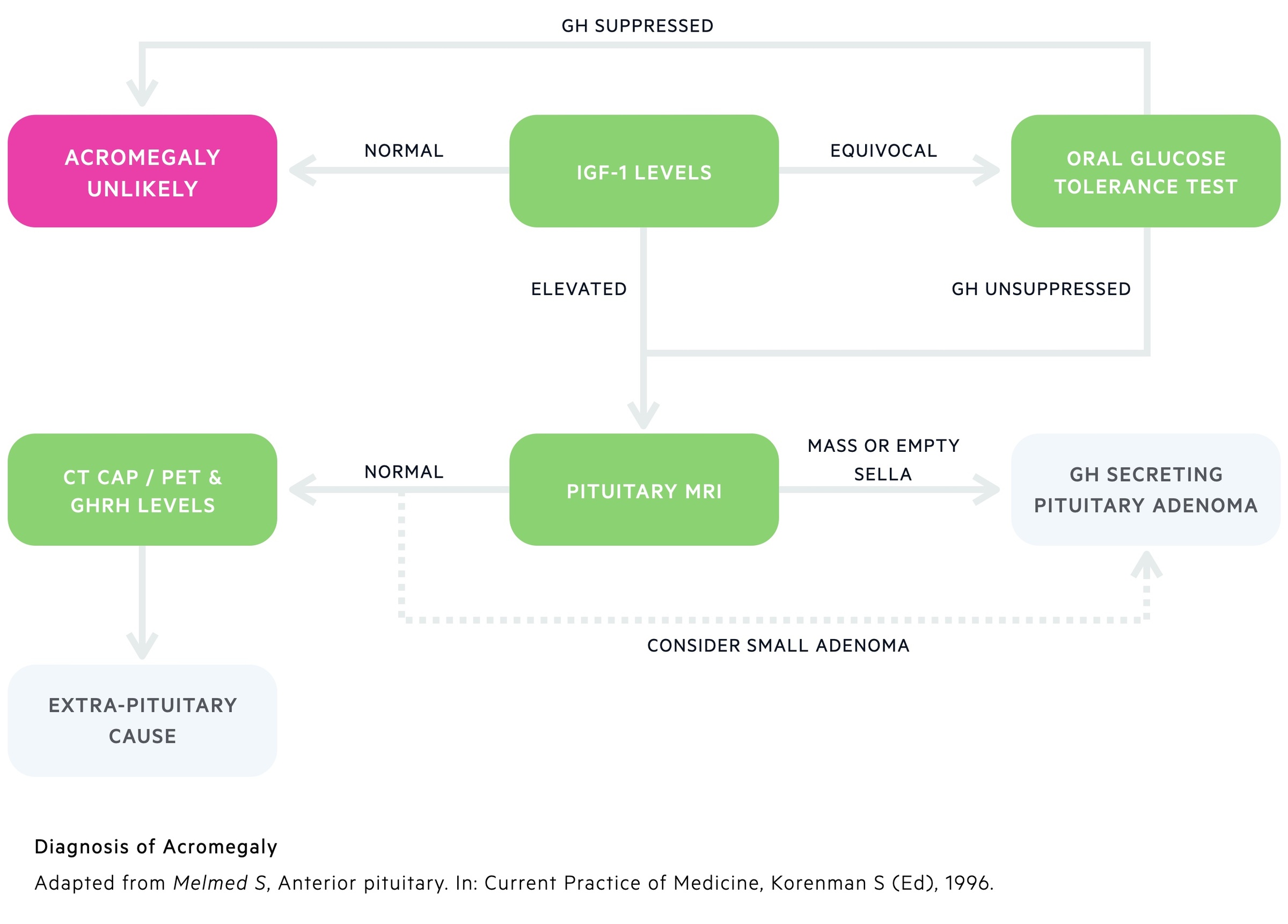

Diagnosis requires biochemical confirmation of GH excess.

The diagnosis of acromegaly is a biochemical one and does not require the classically described phenotypic appearance. Imaging is then used to confirm the underlying aetiology.

Biochemical testing

1. IGF-1 Levels: Whilst GH shows a great deal of variation depending on the time of day and various stressors, IGF-1 has remarkably constant levels. The vast majority of patients with acromegaly will have raised serum IGF-1 that reflects periods of excess GH. Levels guide further investigations:

- High: Essentially confirms diagnosis - can move on to imaging investigations.

- Equivocal: Carry out oral glucose tolerance test.

- Normal: Acromegaly unlikely.

2. Oral glucose tolerance test: This is a highly specific diagnostic test. The patient is given 100g of glucose orally. Serum GH can be measured before and after glucose stimulation. In healthy individuals, GH release is suppressed following the administration of exogenous glucose. In patients with acromegaly, GH levels are unsuppressed.

Pituitary MRI

As mentioned above a somatotroph pituitary adenoma is the most common cause of acromegaly. An MRI of the pituitary can both confirm the diagnosis and guide surgical management. Small adenomas cannot always be seen and extra-pituitary causes may need excluding with further investigations.

Rarely other causes may be found including hypothalamus tumours and pituitary carcinoma.

Further investigations

In patients with suspected extra-pituitary causes a number of investigations may be arranged:

- GHRH levels: Elevated levels indicate excess production from a hypothalamus tumour or ectopic source.

- CT chest, abdomen and pelvis: Used to look for evidence of tumours that may lead to acromegaly through GH or GHRH production (e.g. small cell lung cancer, carcinoid).

- Octreoscan & DOTATATE PET: Further scans that can be used to locate tumours that may produce GH/GHRH.

Management

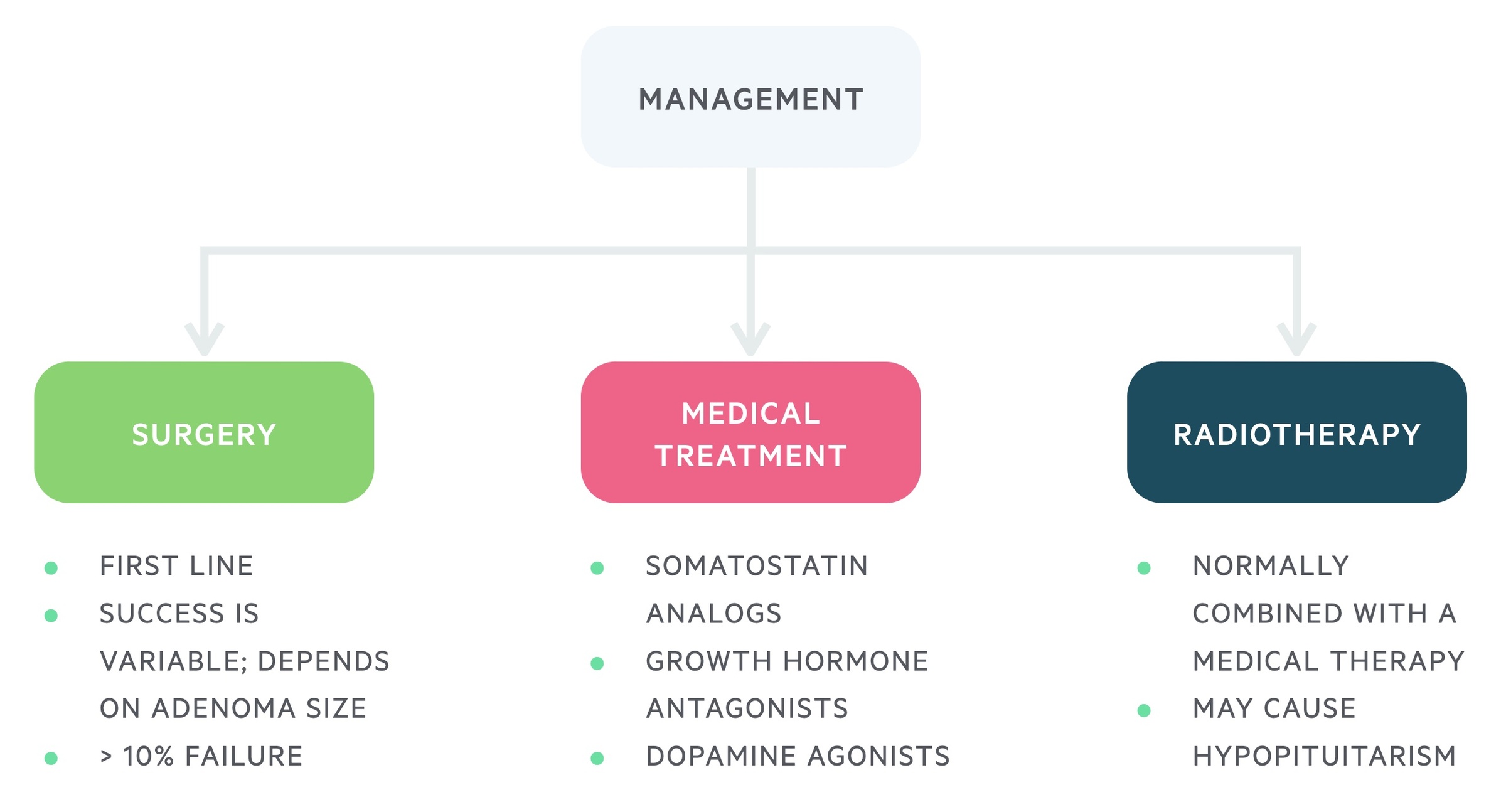

The management of GH secreting pituitary adenomas may involve a number of modalities; surgical, medical and radiotherapy.

Surgery

Transsphenoidal surgery is typically first-line therapy. Success rates are variable, dependent on both the size and location of the adenoma. Microadenomas tend to have better results than macroadenomas.

Early cure is seen in around 80-90% of microadenomas but may be below 50% for macroadenomas.

Medical

Medical treatments may be used in patients who are not operative candidates or where surgery fails to achieve biochemical cure.

The options include:

- Somatostatin analogs (e.g. Octreotide): given as a monthly injection it reduces the release of GH and may cause shrinkage of tumours.

- Growth hormone antagonists (e.g. Pegvisomant): given as daily injection, lowers IGF-1 levels.

- Dopamine agonists (e.g. Bromocriptine): can reduce the release of GH, though they are only effective for a small proportion. Advantage is they can be given as a tablet.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is generally reserved for cases where surgery and medical management fails. It is rarely used as a primary therapy. The biochemical response to radiotherapy can be slow, taking years.

Risks include the development hypopituitarism; therefore, it is generally avoided in those of reproductive age.

Cancer screening

Patients with acromegaly appear to be at increased risk of colorectal cancer and may have an increased risk of thyroid cancer.

Guidance varies country by country based upon the available evidence. There also appears to be an increased risk of other gastro-intestinal malignancies.

Colorectal cancer

Patients may be offered colonoscopy and regular screening from the age of 40. The ongoing frequency of colonoscopy is determined by the findings at index exam and the ongoing acromegaly disease activity (based on 2010 BSG Guidelines)

Thyroid cancer

Routine screening for thyroid cancer is not generally advised. It is unclear if the risk of thyroid cancer is increased or if as a result of the increase in benign nodular disease in acromegaly more cancers are picked up.

Patient presenting with palpable nodularities should be referred for triple assessment (see our Thyroid lumps notes for more details) on an urgent two-week wait basis.

Prognosis

Acromegaly appears to be associated with an increased mortality.

Much of this risk is related to the obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular complications. Studies have reported average survival reduction of up to 10 years in patients with acromegaly.

Evidence suggests that this risk is significantly reduced in patients who demonstrate biochemical cure following surgical management.

Last updated: April 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback