Addison's disease

Notes

Introduction

Addison’s disease (primary adrenal insufficiency) is caused by destruction or dysfunction of the adrenal cortex.

The adrenal glands sit atop each kidney, they are an important endocrine organ responsible for the release of catecholamines (adrenaline, noradrenaline), glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids and sex hormones.

Adrenal insufficiency occurs when there is a reduction of glucocorticoid +/- mineralocorticoid production such that normal physiology is interrupted:

- Primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison's disease): caused by destruction or dysfunction of the adrenal cortex. This is the focus of this note.

- Secondary adrenal insufficiency: caused by a reduction in adrenocorticotropic hormone release. May be seen as part of panhypopituitarism, an isolated deficiency, following brain injury or secondary to medications.

- Tertiary adrenal insufficiency: caused by a reduction in corticotropin-releasing hormone, most commonly seen following chronic glucocorticoid steroid use.

Loss of normal glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid function leads to dehydration, weight loss, abdominal pain, nausea & vomiting and mood disturbance. In women features of androgen deficiency - including loss of libido and hair loss in the axilla/pubic region - may be seen. This rarely affects men where the testes are the primary site of androgen production.

On occasion, patients can present with an 'Addisonian crisis', which refers to a medical emergency caused by profound glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid deficiency that may be triggered by intercurrent illness.

The adrenal gland

The adrenal gland is divided into two functionally distinct components, an outer cortex and an inner medulla.

Also termed the 'suprarenal' gland, the adrenal gland sits atop each kidney. The shape can distinguish laterality with the right gland a pyramidal shape whilst the left is more semilunar.

Adrenal cortex

The adrenal cortex is the outermost aspect of the adrenal gland. It is composed of three layers:

- Zona Glomerulosa: mineralocorticoids - aldosterone is the key mineralocorticoid, release primarily controlled by the renin-angiotensin system (described below).

- Zona Fasciculata: glucocorticoids - release controlled by hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (described below).

- Zona Reticularis: androgens - produces dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA).

In men the testes produce the majority of androgens, as such deficiency of adrenal production does not tend to cause symptoms. However, in women where the other site of production is the ovaries, absence of adrenal androgens may lead to symptoms (see 'Clinical features' below),

Adrenal medulla

The innermost aspect of the adrenal gland, composed of a single layer. Responsible for the production of three hormones:

- Adrenaline

- Noradrenaline

- Dopamine

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

Cortisol secretion is controlled by the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis.

1. Corticotropin-releasing hormone

Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is released by the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. It is transported via the hypophyseal portal system to the anterior pituitary where it stimulates the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

2. Adrenocorticotropic hormone

ACTH, released from the corticotrophs of the anterior pituitary, stimulates the release of cortisol.

The precursor of ACTH is POMC, this is also the precursor of beta-melanocyte-stimulating hormone. In addition, ACTH may be cleaved to form alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone. As a result ACTH excess results in hyperpigmentation (resulting from melanocyte stimulation), particularly affecting the oral mucosa and palmar creases.

ACTH excess is a feature of both Addison's disease (primary adrenocortical insufficiency) and ACTH dependent Cushing's syndrome.

3. Cortisol

Cortisol is released from the adrenal cortex in response to ACTH. It exerts negative feedback on the release of both ACTH and CRH.

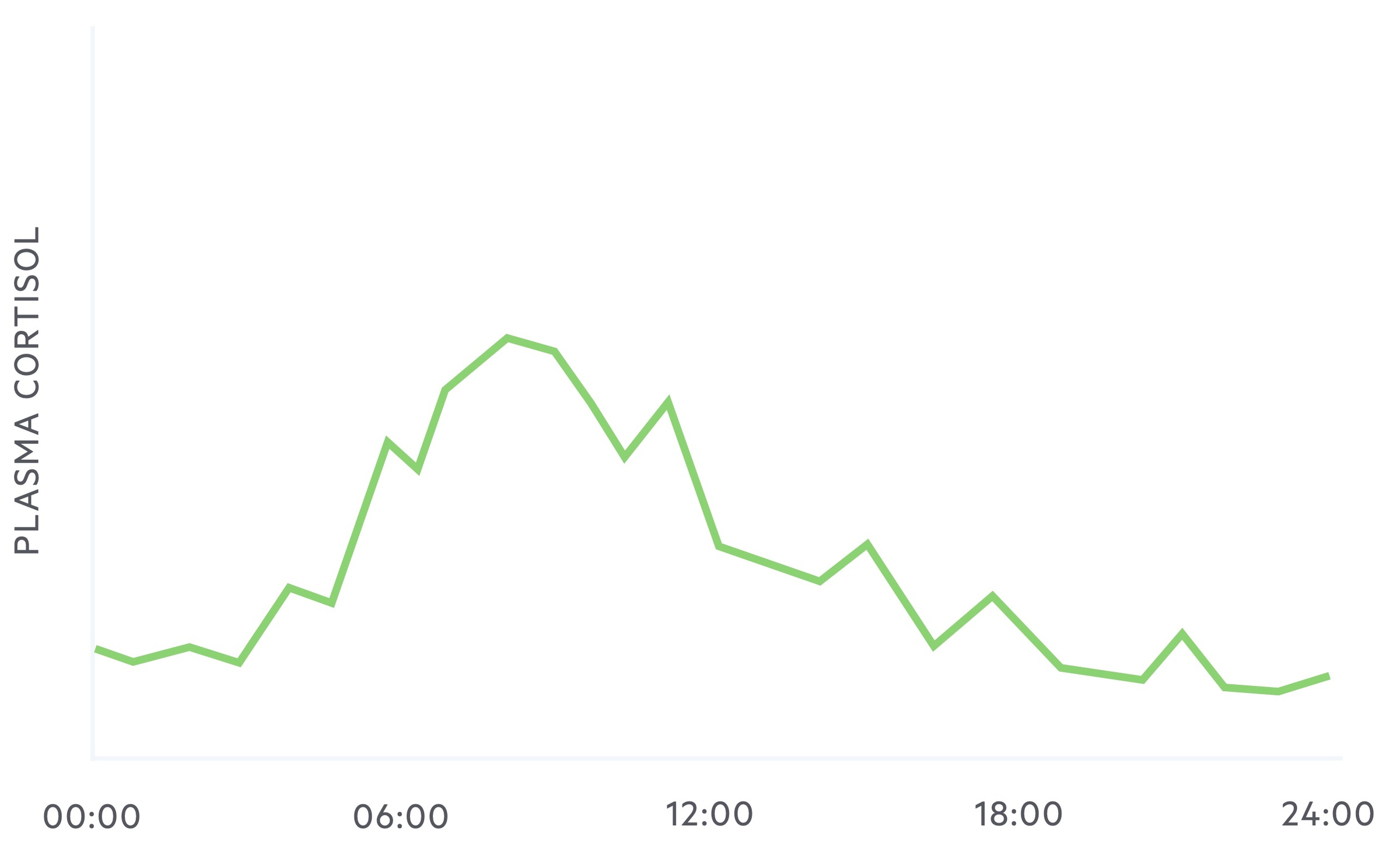

Cortisol exhibits diurnal variation, that is to say, the plasma concentration of cortisol levels vary during a 24 hour period.

It reaches a zenith (highest point) at around 8 am and a nadir (lowest point) at around midnight to 1am.

Renin-angiotensin system

Aldosterone release is primarily controlled by the renin-angiotensin system.

1. Renin

Renin, a proteolytic enzyme, is released by granular cells of the juxtaglomerular apparatus in response to:

- Renal artery hypotension

- Sympathetic stimulation

- Reduced sodium levels in the distal tubal

In the blood renin cleaves angiotensinogen into angiotensin I.

2. Angiotensin

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), found primarily in the vascular endothelium of the lungs, cleaves angiotensin I to give angiotensin II.

Angiotensin II has multiple functions:

- Stimulates adrenal cortex to release aldosterone

- Causes vasoconstriction

- Increases sodium reabsorption

- Stimulates the release of anti-diuretic hormone (ADH)

- Increases sympathetic permissiveness

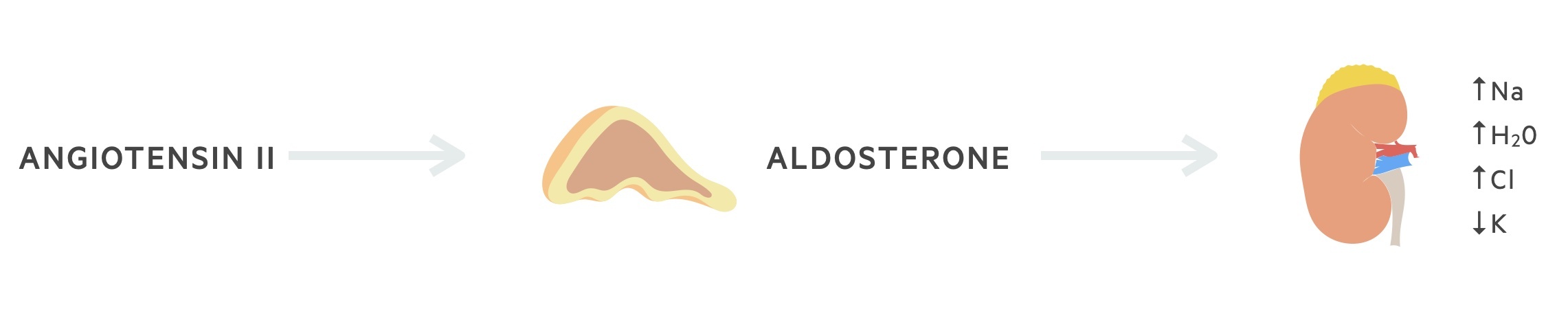

3. Aldosterone

Aldosterone is a mineralocorticoid released from the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal cortex. It is released in response to:

- Angiotensin II (primary stimulus)

- ACTH

- Potassium levels

Its primary action is to increase the number of epithelial sodium channels in the distal tubule. This results in sodium and water reabsorption and potassium excretion.

Aetiology

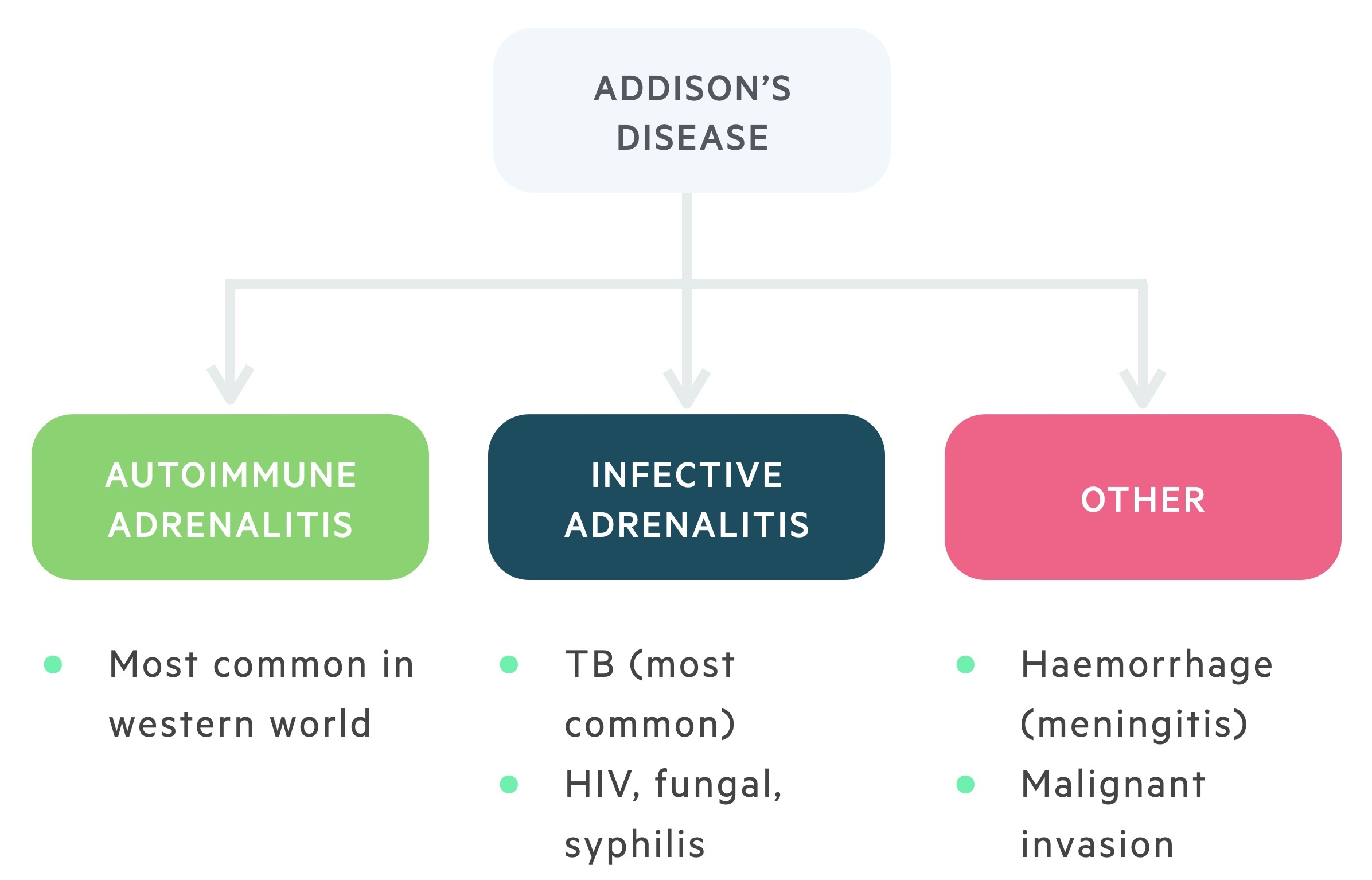

Worldwide, the most common cause of adrenal insufficiency is tuberculosis.

Autoimmune adrenalitis

The most common cause of adrenocortical insufficiency in the western world is the autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex. This is more common in women.

It is suggested that autoantibodies target enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of steroids. One of the main targets for autoimmune destruction is the enzyme 21-hydroxylase.

Infective adrenalitis

Though rare in the UK, tuberculosis induced infective adrenalitis is the most common cause of adrenocortical insufficiency worldwide. This is the setting in which Thomas Addison first described the condition.

Other infective causes include HIV (and associated opportunistic infections), disseminated fungal infection and syphilis.

Other (rare)

The remaining causes of Addison's disease are uncommon. In Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome adrenal haemorrhage occurs secondary to septicaemia.

Infiltrative disease as a result of malignant metastasis or amyloid deposits may cause adrenal insufficiency. Bilateral adrenalectomy is an iatrogenic cause of Addison's disease.

Clinical features

Addison’s disease is often diagnosed late due to its non-specific presentation.

Addison's disease may present with an acute Addisonian crisis or (more commonly) with chronic disease.

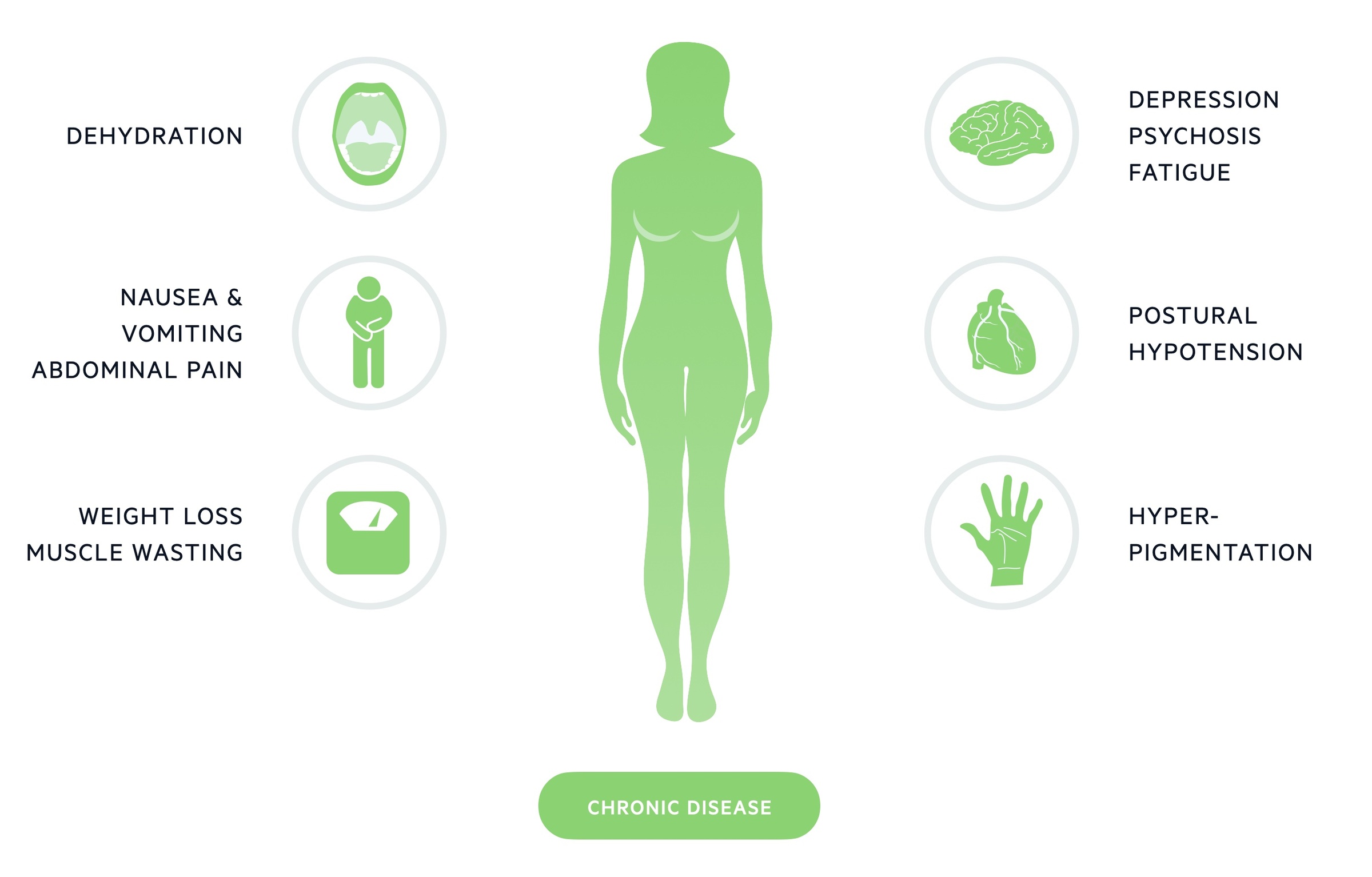

Chronic disease

The majority of cases present with a chronic, insidious onset. Features may be vague and non-specific with patients complaining of fatigue, anorexia and abdominal pain.

In women features of androgen deficiency may be seen (this is rarely seen in men where the testes provide the majority of androgen production). This may include:

- Loss of libido

- Loss of hair in axillary/pubic regions

A clinician may detect muscle wasting, examine for postural hypotension and note hyperpigmentation (particularly the mucous membranes and palmer creases).

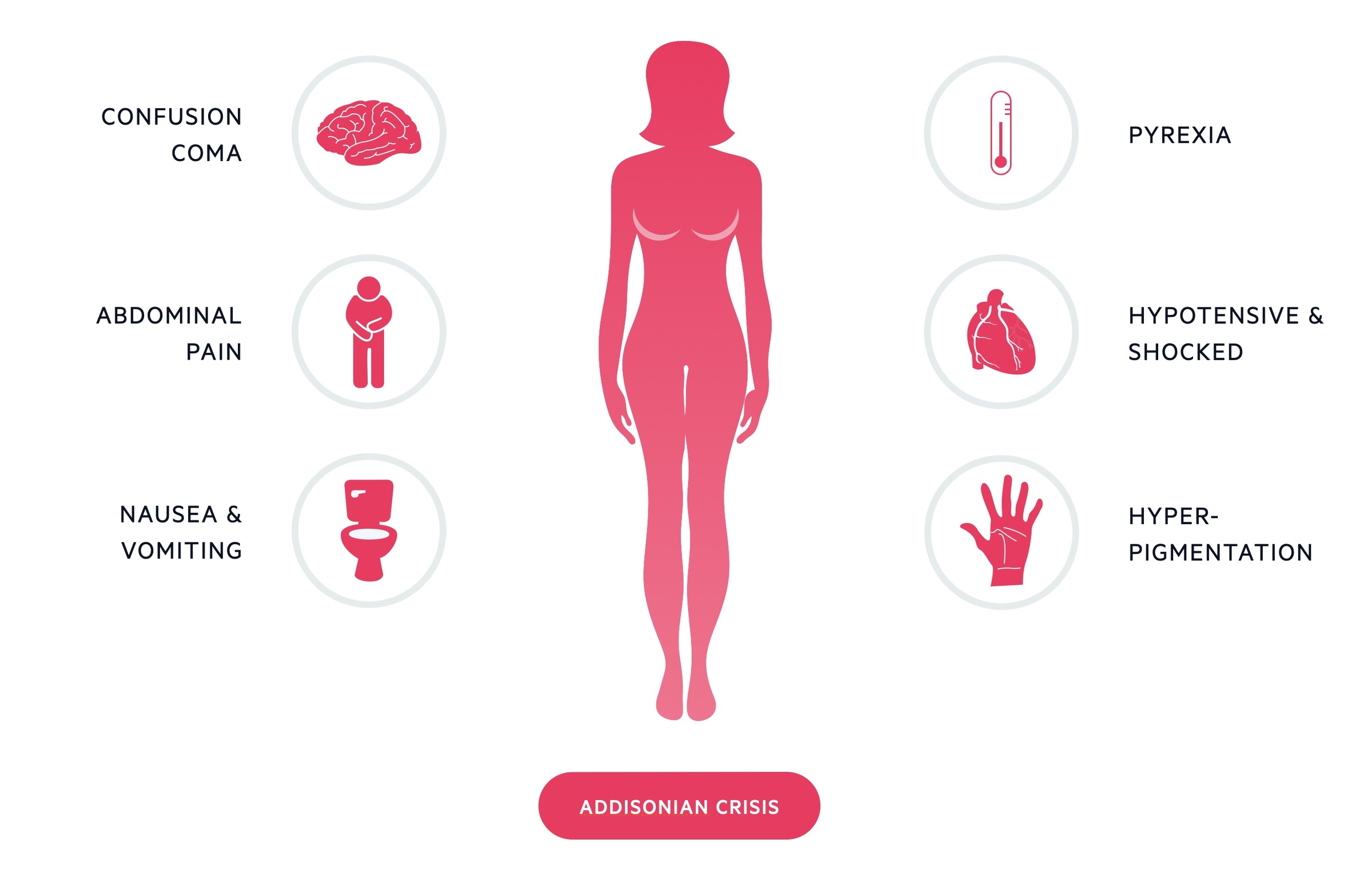

Addisonian crisis

An Addisonian crisis is a potentially life-threatening presentation of Addison’s disease. It is caused by a significant deficiency in glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids. It is most commonly seen in tertiary adrenal insufficiency (termed an 'adrenal crisis') as a result of the sudden withdrawal of exogenous steroids.

In Addison's disease it may occur following an acute decompensation where an additional stress (e.g. infection) results in an exacerbation of a pre-existing deficiency. Bilateral adrenal gland haemorrhage can also result in a crisis.

It presents with symptoms of profound glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid deficiency. These include dehydration, hypotension and confusion. Blood tests may reveal hyponatraemia, hyperkalaemia and hypoglycaemia.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Addison’s may utilise both blood tests and stimulation tests.

1. Blood tests

Biochemistry can be indicative. A deficiency in mineralocorticoids (aldosterone) may lead to hyponatraemia (seen in up to 90%) and hyperkalaemia (seen in around 30-50% of cases).

Serum cortisol, measured at 8-9 am (when it should be highest in those with routine sleeping patterns) may be used as a screening tool. It should be noted this does not distinguish between types of adrenal insufficiency (i.e. primary, secondary, tertiary). In addition there is not clear 'cut-off' that can conclusively determine whether or not someone has adrenal insufficiency.

- < 100 nmol/L: adrenal insufficiency very likely

- 100–500 nmol/L: adrenal insufficiency possible

- > 500 nmol/L: adrenal insufficiency unlikely

A plasma ACTH level may help distinguish between primary and secondary/tertiary adrenal insufficiency:

- High: indicative of Addison's disease (primary adrenal insufficiency)

- Normal: inconclusive

- Low: indicative of secondary/tertiary adrenal insufficiency

2. Short synacthen test

This test involves the IV administration of 250 mcg of tetracosactide, a synthetic analogue of ACTH. Cortisol is measured at three time points: 0 (i.e. immediately before), 30 and 60 minutes following administration. The test is carried out in the morning, normally commencing at 8 am.

The baseline reading of cortisol should be >180-190 nanomol/L. Serum cortisol > 500–550 nanomol/L either before or following the ACTH is considered normal.

Management

The management of adrenal insufficiency involves replacement of deficient hormones.

Glucocorticoid replacement

Glucocorticoids are replaced with hydrocortisone, 15-30 mg/day given in divided doses.

An example regime may be 10 mg in the morning, 5 mg at noon and 5 mg in the evening. Regimes should follow the pattern of work in shift workers (i.e 10 mg dose on waking regardless of time of day).

Mineralocorticoid replacement

Mineralocorticoids are replaced with fludrocortisone, typically around 50-300 mcg per day.

Fludrocortisone is typically used, which has mineralocorticoid activity 125 times that of hydrocortisone. The dose of fludrocortisone can be adjusted to levels of exercise and metabolism.

Androgen replacement

This is an area where our understanding and the evidence base is developing. There is some evidence that DHEA replacement in certain settings improves mood and quality of life in women.

Generally caution is advised until there is more long-term safety data. It may be considered by specialists in women with adequate glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement with significant ongoing mood or quality of life disturbance.

Patient education

Patients must understand that treatment for Addison’s disease is (for the majority) lifelong. Intercurrent illness requires adjustment of the glucocorticoid dose. For example, a temperature > 37.5oC should prompt a doubling of dose.

Patients should be able to promptly identify an Addisonian crisis as well as carry a steroid card and MediAlert identification.

Addisonian crisis

An Addisonian crisis is a medical emergency requiring prompt recognition and treatment.

It is managed with IV hydrocortisone (100mg) and IV fluid rehydration. Cardiac, electrolyte and blood sugar monitoring should be arranged.

100mg of hydrocortisone has sufficient mineralocorticoid activity and acutely fludrocortisone is not necessary. Following initial resuscitation, a hydrocortisone/dextrose infusion may be given with a target of 400mg of hydrocortisone over a 24 hour period. This will need to be reduced over the coming days, specialist input should be sought.

Last updated: November 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback