Primary hyperparathyroidism

Notes

Overview

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is characterised by excess production of parathyroid hormone (PTH) by one or more parathyroid glands resulting in elevated serum calcium.

The condition is most commonly related to a parathyroid adenoma (80-85% of cases) or parathyroid hyperplasia. Rarely it is related to a parathyroid carcinoma.

PTH is a key hormone involved in calcium and phosphate homeostasis, its excess leads to elevated serum calcium. PHPT is the most common cause of hypercalcaemia in the general population.

Parathyroidectomy offers excellent chance of cure in patients who meet the indications for surgery.

Types of hyperparathyroidism

Although this note focuses on primary hyperparathyroidism, it is worth considering it within overall context of PTH excess.

- Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT): characterised by excess production of PTH by one or more parathyroid glands causing elevated serum calcium. Caused by parathyroid adenoma (most common), hyperplasia and carcinoma (rare)

- Secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT): characterised by excess PTH production secondary to low serum calcium, typically due to chronic kidney disease or vitamin D deficiency.

- Tertiary hyperparathyroidism (THPT): characterised by autonomous PTH excess due to parathyroid hyperplasia in response to longstanding secondary hyperparathyroidism - seen in patients with chronic kidney disease. Like PHPT and unlike SHPT this is associated with hypercalcaemia.

Epidemiology

Primary hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause of hypercalcaemia in the general population.

PHPT and malignant hypercalcaemia together account for the majority of cases of hypercalcaemia. Malignant disease is the most common cause of hypercalcaemia in the inpatient population.

The prevalence is estimated to be between 1 and 4 per 1000 of the general population. Its incidence increases with age, in particular affecting post-menopausal women.

Pathology

PHPT is most commonly caused by a parathyroid adenoma.

- Parathyroid adenoma: approximately 80-85% of cases. These are autonomous nodes that produce PTH hormone but do not respond to normal feedback mechanisms. Occasionally double adenomas are seen (3-5%).

- Parathyroid hyperplasia: around 15-20% of cases are caused by multi-gland hyperplasia.

- Parathyroid cancer: around 1% of cases. Difficult to diagnoses but may be suspected in patients with greatly elevated PTH and calcium or occasionally based on imaging findings.

Primary hyperparathyroidism may occur as part of an identifiable genetic disorder such as multiple endocrine neoplasia which is characterised by primary hyperparathyroidism, pituitary adenomas and pancreatic tumours. There are a number of other rare familial forms. Genetic testing is indicated where onset and features are indicative of an underlying cause.

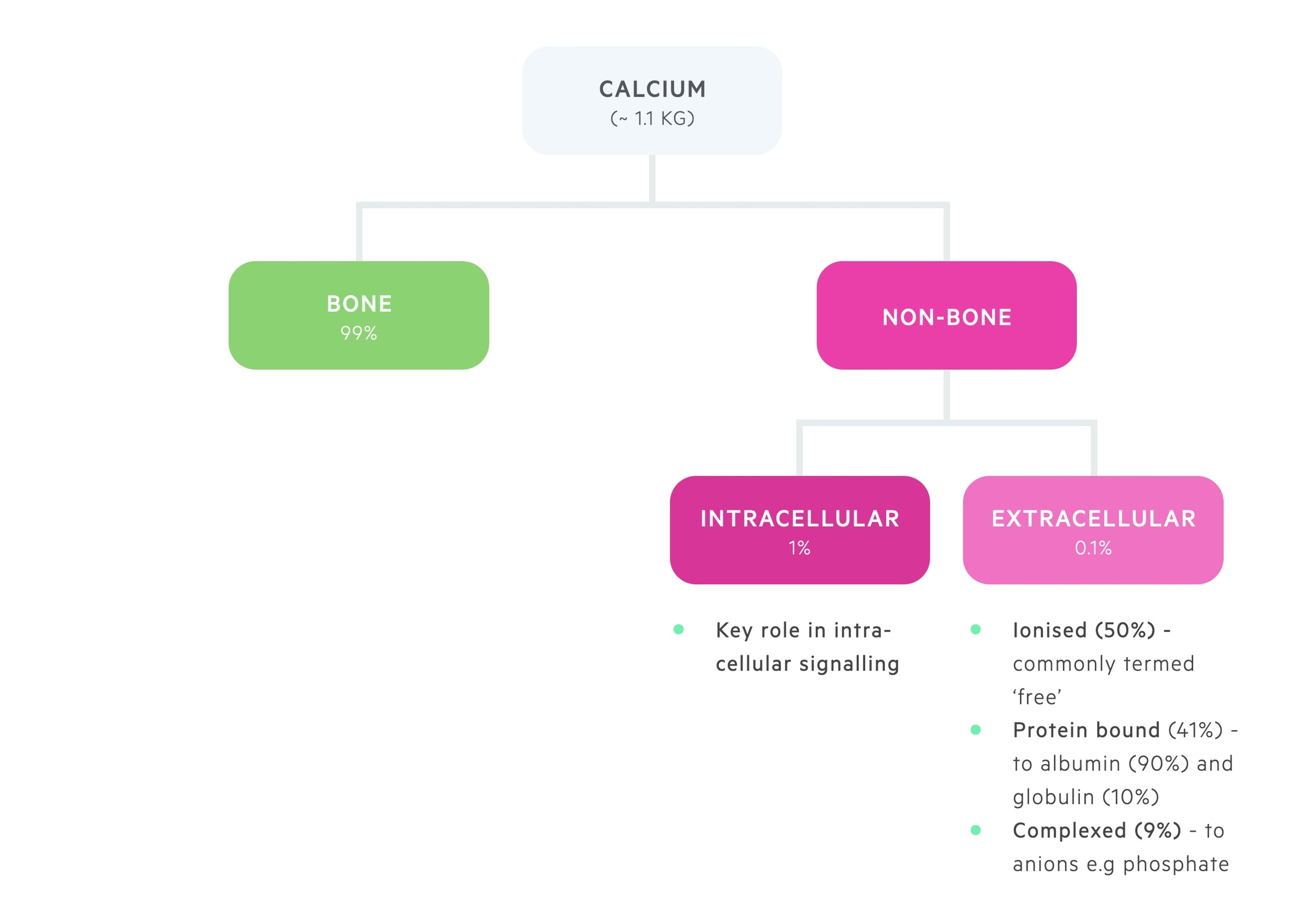

Calcium physiology

Calcium is distributed between bone and the intra- and extra-cellular compartments.

The majority of body calcium, 99%, is stored in bone.

1% of total body calcium is found within the intracellular compartment. Here it plays a key role in intracellular signalling.

0.1% of total body calcium is found within the extracellular pool, this is divided into:

- Ionised (50%): metabolically active, or ‘ionised’, free pool of calcium.

- Bound (41%): bound to albumin (90%) and globulin (10%).

- Complexed (9%): forms complexes with phosphate and citrate.

The balance between stored calcium and the extracellular pool of calcium is a closely regulated process. It is controlled by the interaction of three hormones; parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D and calcitonin.

Decreased extracellular calcium is detected by the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) on the parathyroid gland. The parathyroid glands respond to the fall in serum calcium by releasing PTH. PTH stimulates the resorption of calcium from bone, activation of vitamin D (leads to calcium absorption from enterocytes) and increased renal tubular reabsorption of calcium.

Conversely, a rise in extracellular calcium detected by the CaSR has the opposite effect. It leads to a reduction in the release of PTH and stimulates the release of calcitonin. This combined effect helps decrease bone resorption and promotes calcium excretion in the kidneys.

Serum calcium

Normal serum calcium levels range from 2.2-2.6 mmol/L. Levels > 2.6 mmol/L are defined as hypercalcaemia. Depending on the level of serum calcium, hypercalcaemia can be graded:

- Mild: 2.6-3.0 mmol/L

- Moderate: 3.0-3.5 mmol/L

- Severe: > 3.5 mmol/L

The proportion of extracellular calcium that is ionised or 'free' is dependent on the amount bound to albumin. Serum calcium must be 'corrected' with reference to albumin levels. Typically 0.1 mmol/L is added to the level for every 4 g/L below 40 g/L the albumin is, with a subtraction if it is above 40 g/L.

Interestingly, protein binding of calcium is altered by pH. Acidosis leads to a decrease in calcium binding with albumin and alkalosis an increase.

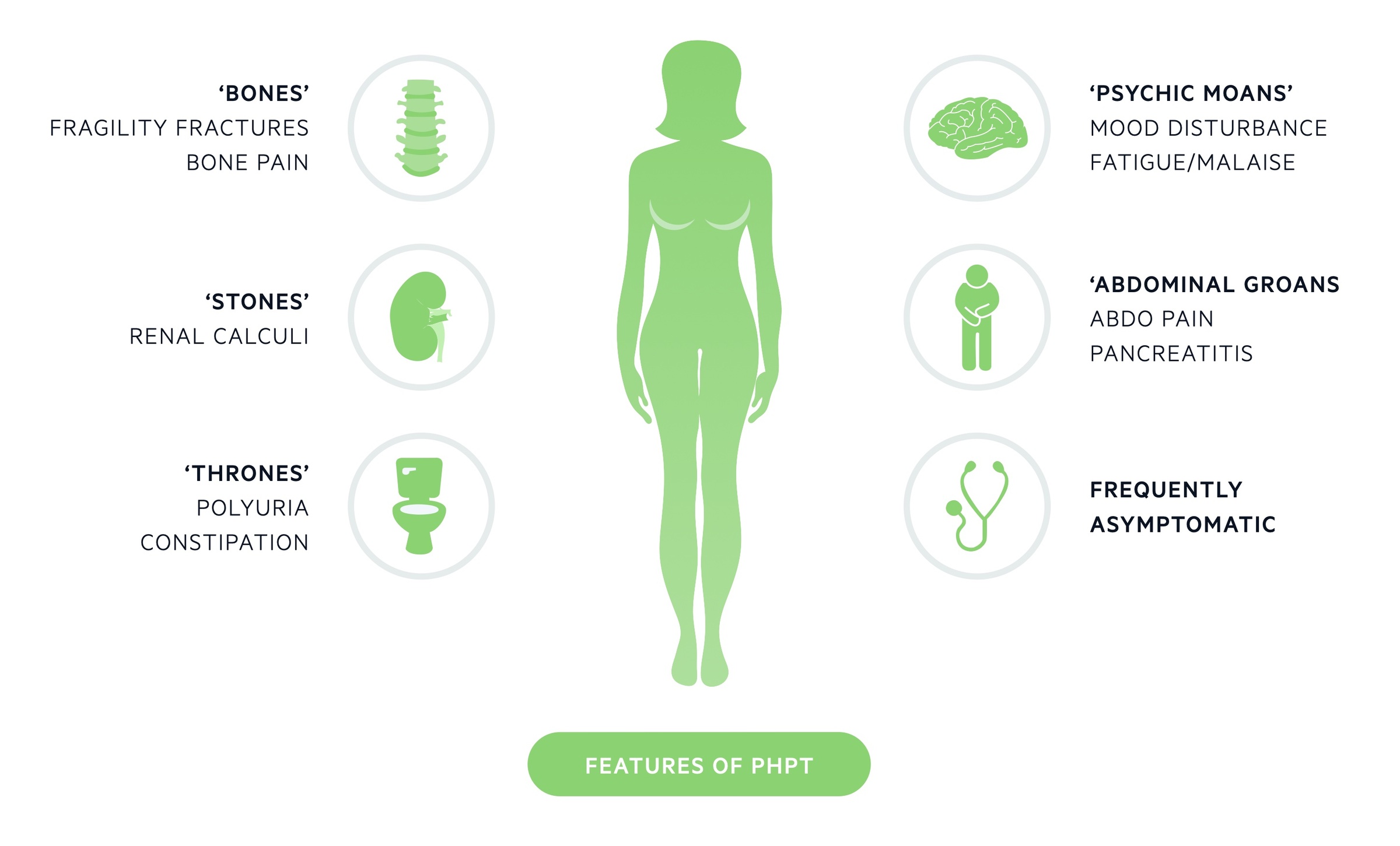

Clinical features

PHPT is most commonly asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally during blood tests.

In ‘developed’ countries where access to medical tests is more readily available, an estimated 80% of diagnosed cases are asymptomatic.

Clinical features, when present, may reflect both the hypercalcaemia and the raised PTH. In those who are symptomatic the classic phrase ‘bones, stones, thrones, abdominal groans, and psychic moans’ can act as an aide-mémoire.

- Bones - osteitis fibrosa cystica (classical though rare), fragility fractures

- Stones - renal calculi

- Thrones - polyuria, constipation

- Abdominal groans - abdominal pain, N&V, pancreatitis

- Psychic moans - mood disturbance, depression, fatigue, psychosis

As discussed in the diagnosis section below, symptoms, when present, are often vague and non-specific - a high index of suspicion is needed.

Symptoms

- Fatigue

- Myalgia

- Mood changes

- Depression

- Insomnia

- Polydipsia

- Polyuria

- Constipation

- Fragility fracture

- Renal colic

Signs

- Dehydration (skin turgor, dry mucous membranes)

- Hypertension

- Confusion (severe disease)

Specific manifestations

Renal calculi: relatively common in those with symptomatic presentations. Typically calcium oxalate stones though may be calcium phosphate.

Osteitis fibrosa cystica: this condition is characterised increased bone turnover and subperiosteal bone resorption secondary to elevated PTH. Patients experience bone pain and X-rays may reveal osteoclastic brown tumours and salt and pepper appearance of the skull.It is rarely seen today, likely in part due to more effective treatment and the increasing proportion of patients being diagnosed with mild or asymptomatic disease.

Parathyroid crisis: rarely seen, affects patients with markedly elevated serum calcium (> 3.8 mmol/L) and results in acute confusion or coma. Other features include abdominal pain, bone pain, renal calculi and renal impairment.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PHPT relies on the demonstration of raised calcium in the presence of a raised or inappropriately normal PTH.

Albumin-adjusted serum calcium

NICE guidelines 132 (2019) advise testing albumin-adjusted serum calcium for anyone with the following features:

- Symptoms of hypercalcaemia including:

- Thirst

- Frequent or excessive urination

- Constipation

- Osteoporosis or a previous fragility fracture

- A renal stone

- An incidental finding of elevated albumin-adjusted serum calcium (2.6 mmol/litre or above)

The guidelines also advise you consider albumin-adjusted serum calcium for people with chronic non-differentiated symptoms (e.g. fatigue, mild confusion, bone, muscle or joint pain, anxiety, depression, irritability, low mood, apathy, insomnia, frequent urination, increased thirst and digestive problems).

Finally they advise a repeat albumin-adjusted serum calcium measurement if the first measurement is either:

- 2.6 mmol/litre or above or

- 2.5 mmol/litre or above and features of primary hyperparathyroidism are present

Parathyroid hormone

NICE guidelines 132 (2019) advise parathyroid hormone (PTH) measurement is indicated in those whose albumin-adjusted serum calcium level is either:

- 2.6 mmol/litre or above on at least 2 separate occasions or

- 2.5 mmol/litre or above on at least 2 separate occasions and primary hyperparathyroidism is suspected

At the time the PTH is sent a repeat albumin-adjusted serum calcium should be measured. The majority of patients with PHPT (around 80-90%) will have an elevated PTH above the upper limit of normal. Approximately 10-20% will have a PTH in the upper half of the normal range.

Alternative diagnoses - including malignant hypercalcaemia must be considered in those with hypercalcaemia and a suppressed PTH.

Excluding FHH

Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia or FHH is an autosomal dominant condition caused by a mutation to calcium-sensing receptors (CaSR). CaSRs play an important role in calcium regulation:

- Parathyroid gland: CaSRs enable the parathyroid gland to sense changes to calcium levels and respond appropriately.

- Kidneys: CaSRs have a number of complex functions that appear to increase calcium excretion in the urine when serum levels are raised.

FHH normally causes a mildly elevated calcium with a PTH that is either mildly elevated or at the upper limit of normal. As such it is excellent at biochemically mimicking PHPT. It can be distinguished by looking for the hypocalciuria that is present in FHH but absent in PHPT.

NICE guidelines 132 (2019) advise one of the following tests to exclude FHH:

- 24-hour urinary calcium excretion

- Random renal calcium:creatinine excretion ratio

- Random calcium:creatinine clearance ratio

Pre-op localisation

Following diagnosis, localisation of the pathological parathyroid gland(s) is required in those considering surgery.

Patients with biochemically confirmed PHPT who are planning to undergo surgery require pre-operative localisation studies.

The aim is to localise the parathyroid adenoma or glands that are causing disease to help guide targeted operative management.

USS

First line imaging consists of an ultrasound scan (USS) of the neck which may identify abnormal parathyroid glands.

In addition it is able to identify thyroid pathology that may influence both pre-operative and operative considerations. USS is always, to a degree, operator dependent but the sensitivity is approximately 60-70%.

Technetium-99 sestamibi

This is a study involving ionizing radiation termed sestamibi for short. It involves the injection of technetium-99m radiolabelled sesta (6) -methoxyisobutylisonitrile (MIBI) which is taken up by parathyroid tissue. Images are taken at multiple time intervals and pathology is demonstrated in around 80% of cases.

The scan may be augmented in a number of ways including performing it in combination with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

Additional localisation techniques

Knowledge of this goes somewhat beyond what is expected at an undergraduate level. The truth is localisation of parathyroid disease can be very challenging in a relatively small proportion of patients.

There are a number of additional tests that with time may become more routinely used. Currently they tend to be restricted to patients in whom first-line techniques have failed or in the re-operative setting (i.e. the first procedure failed to cure PHPT).

- Four-dimensional CT (4DCT): this involves three-dimensional CT with the added ‘dimension’ of monitoring the perfusion of contrast over time. It is excellent at localising adenomas particularly in those with recurrent or persistent PHPT after previous surgery. Its use is somewhat limited by the very high radiation burden - far higher than sestamibi - as such it must be used with caution, particularly in younger patients.

- 18F PET-CT: has successfully been used to identify abnormal parathyroid glands. Early studies indicate excellent results but its role has not been firmly established.

- Selective venous sampling: this is an invasive procedure that requires a highly skilled and experienced interventional radiologist. Can help to localise a gland that is producing excess PTH. Typically reserved for the re-operative setting where other localisation strategies have failed.

Management

Surgery is the only curative therapy for PHPT.

Operative management

Referral for surgery

NICE guidelines 132 advise referral to a surgeon experienced in parathyroid surgery for a discussion regarding surgical management in the following circumstances:

- Symptoms of hypercalcaemia such as thirst, frequent or excessive urination, or constipation or

- End-organ disease (renal stones, fragility fractures or osteoporosis) or

- An albumin-adjusted serum calcium level of 2.85 mmol/litre or above

They also advise that any patient with confirmed PHPT can be considered for referral to an appropriate surgeon. One of the classical indications for surgery, not explicitly mentioned by NICE, is patients under the age of 50. Surgery is also indicated if there is any indication of parathyroid cancer (detection and management not covered here in detail).

Surgical options

A choice of a targeted approach or 4 gland exploration (direct visualisation of each gland to aid diagnosis) may be considered depending on the results of pre-operative localisation studies (see chapter above).

Many centres utilise intra-operative PTH monitoring to help confirm the removal of the causative tissue. Post-operatively the PTH and serum calcium are normally measured that night and the following morning with further checks in clinic.

Complications

- Hypocalcaemia: this is common. In patients with an adenoma, suppression of the unaffected glands may take some time to resolve. At times, if all glands have been explored, accidental damage or de-vascularisation may have occurred of remaining glands. In most patients it resolves though supplements may be required in the short term. In a smaller proportion long-term supplements may be needed.

- Recurrence: this may affect up to 5% of patients. Depending on the first procedure - targeted vs 4 gland exploration - and the findings at surgery (all glands visualised or suspicion of a missing ectopic gland) help guide further management.

- Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy: There is a risk of damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which when unilateral results in a hoarse voice - this is rare affecting less than 1% in experienced hands. If bilateral injury occurs (very rare) vocal cord paralysis and stridor can occur necessitating a tracheostomy.

Non-operative management

In patients who decline surgery or are unsuitable, calcimimetics (e.g. cinacalcet) may be trialled. NICE guidelines 132 advise restricting use to those with:

- 2.85 mmol/litre or above with symptoms of hypercalcaemia or

- 3.0 mmol/litre or above with or without symptoms of hypercalcaemia

Calcimimetics do not represent a cure, are ineffective in a significant minority and may cause a number of adverse effects.

Patients should receive a holistic review. Hypertension should be appropriately managed and bone health reviewed with osteoporosis treated if indicated.

Last updated: April 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback