Hiatus hernia

Notes

Overview

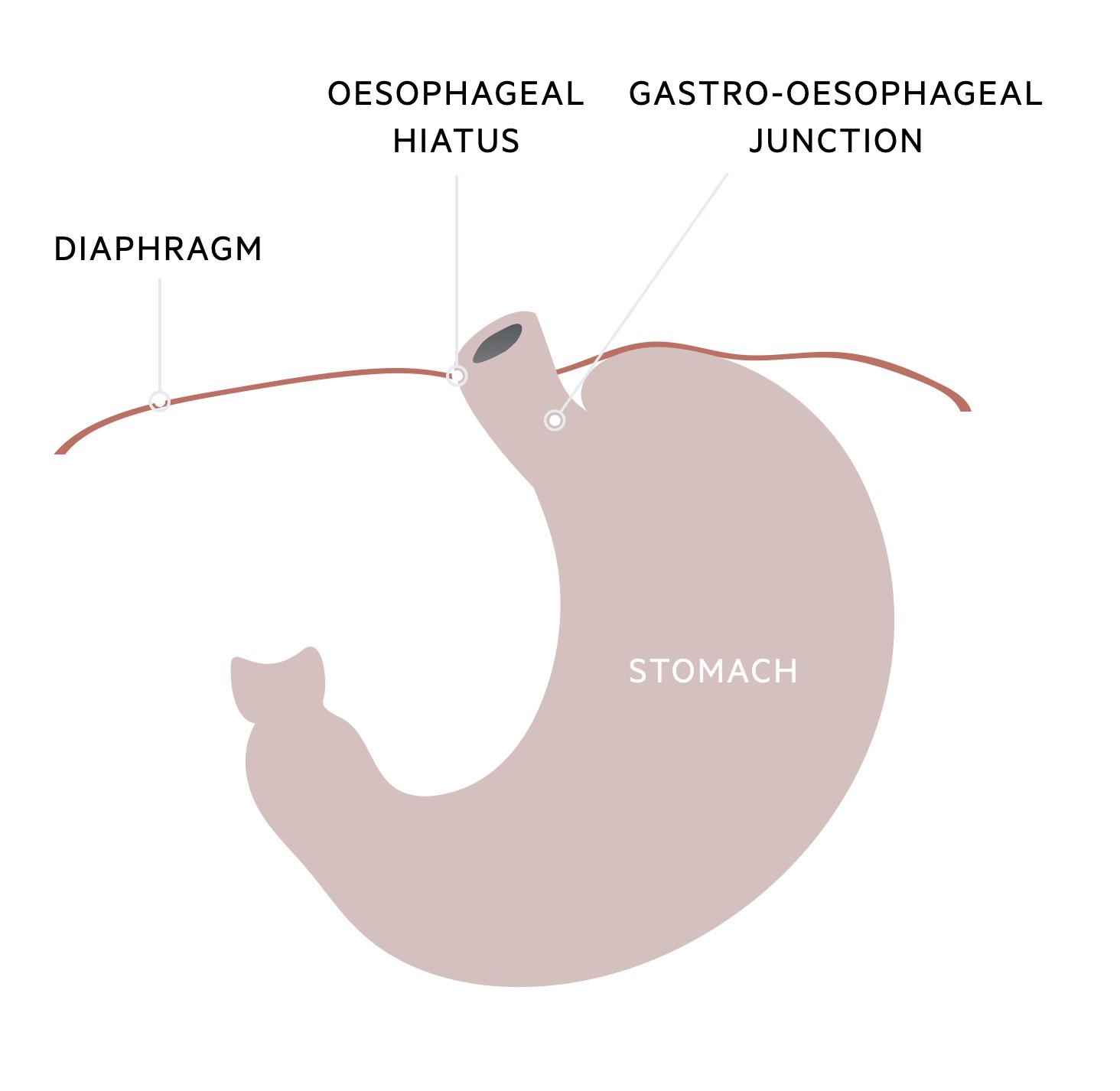

A hiatus hernia refers to the herniation of part of the stomach through the diaphragmatic oesophageal hiatus.

Hiatus hernia is an extremely common anatomical abnormality. It refers to the herniation of part of the stomach through an opening in the diaphragm known as the oesophageal hiatus. This opening functions to allow the oesophagus to pass through the diaphragm into the abdominal cavity.

The majority of hiatal hernias are asymptomatic and found incidentally during endoscopy or imaging (e.g. CT or barium swallow). They may be associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux due to disruption of the lower oesophageal sphincter. Management depends on the type of hiatal hernia and associated symptoms.

Epidemiology

There is a huge variation in the prevalence of hiatus hernia.

Hiatal hernias are usually identified as an incidental finding when endoscopy or imaging is being performed for another reason. Traditional risk factors for hiatus hernia include older age, male sex, and obesity. In one study, the prevalence of hiatus hernia was 9.9% among 3200 patients undergoing CT imaging. This number varies greatly depending on the study.

Classification

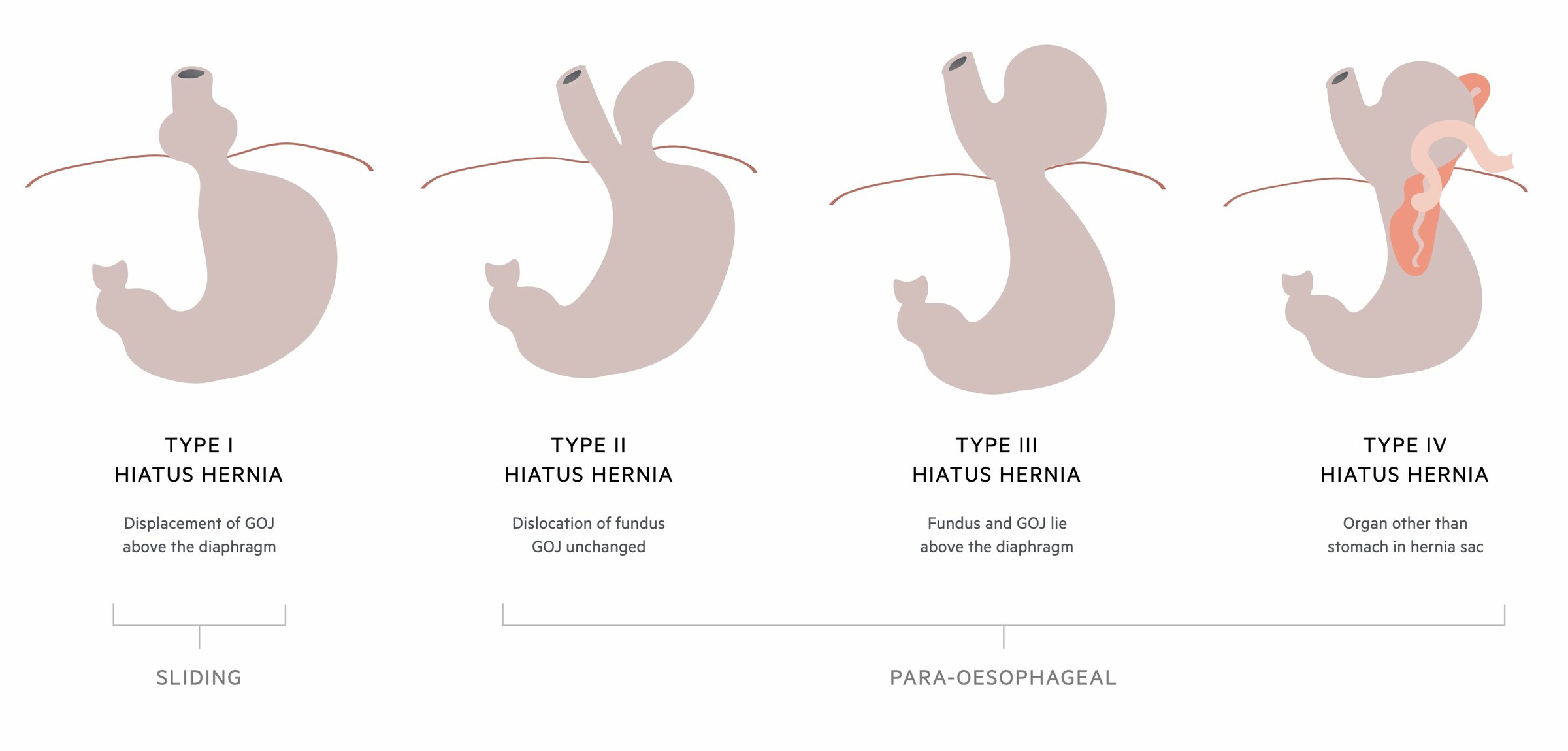

Hiatal hernias can be divided into four main types.

There are four types of hiatus hernia.

- Type I (sliding): displacement of the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ) above the diaphragm. Account for >95% of hiatal hernias and usually asymptomatic

- Type II (para-oesophageal): herniation of the gastric fundus through a defect in the phrenoesophageal membrane. The GOJ remains below the diaphragm. The least common type of para-oesophageal hernia

- Type III (para-oesophageal): a combination of type I and II hernias. Both the gastric fundus and GOJ herniate through the oesophageal hiatus and lie above the diaphragm. The most common type of para-oesophageal hernia

- Type IV (para-oesophageal): characterised by the presence of other organs within the hernial sac above the diaphragm (e.g. large bowel, small bowel). Usually, there is significant displacement of the stomach above the diaphragm due to a large defect in the phrenoesophageal membrane. As the stomach herniates through it may twist on its longitudinal or horizontal axis leading to a gastric volvulus

NOTE: para-oesophageal hernias are sometimes referred to as ‘rolling’ hiatus hernias.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

A hiatus hernia is commonly associated with loss of the normal gastro-oesophageal junction.

The oesophagus joins the stomach at the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ), which is usually demarcated by the z-line otherwise known as the squamocolumnar junction. The lower end of the oesophagus is tightly bound to the diaphragm by the phrenoesophageal membrane. Food that enters the stomach must pass through the GOJ, which is maintained by two sphincters:

- Lower oesophageal sphincter

- Crus of the diaphragm

The lower oesophageal sphincter is a complex valvular structure that helps to prevent reflux of stomach contents into the tubular oesophagus. It is a high-pressure zone approximately 2 cm in length. The top margin is just inferior to the z-line. This sphincter, alongside the Crus of the diaphragm, helps to prevent reflux of gastric content into the oesophagus, especially during increases in intra-abdominal pressure.

Several risk factors increase the risk of developing a hiatus hernia, which includes;

- Obesity

- Pregnancy

- Trauma

- Previous gastro-oesophageal surgery

- Increasing age

- Congenital defects

These factors may contribute to the development of a hiatal hernia through widening of the oesophageal hiatus, increased laxity of the phrenoesophageal membrane and shortening of the oesophagus that pulls the stomach upwards. As the integrity of the GOJ is lost, pathological reflux of gastric contents can occur leading to symptoms of heartburn. In fact, > 50% of patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux will have a type I hiatus hernia.

Clinical features

Patients with a small type I hiatus hernia are commonly asymptomatic.

Patients with a hiatus hernia are frequently asymptomatic, especially with small type I hiatal hernias. If symptomatic, patients commonly experience heartburn due to loss of the normal sphincter function of the gastro-oesophageal junction. As the hernia enlarges, patients are more likely to experience symptoms.

Signs and symptoms

- Asymptomatic

- Heartburn

- Regurgitation

- Dysphagia

- Epigastric pain

- Post-prandial fullness

- Nausea

- Retching

NOTE: patients with para-oesophageal hernias are less likely to experience reflux and more at risk of mechanical complications such as gastric volvulus leading to dysphagia, post-prandial pain and distension

Diagnosis & investigations

The diagnosis of hiatus hernia is commonly made on imaging or during upper GI endoscopy.

A hiatus hernia is usually an incidental finding during the work-up of a patient with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. The diagnosis can be made during upper GI endoscopy, barium swallow, high-resolution manometry, or imaging (e.g. x-ray, CT).

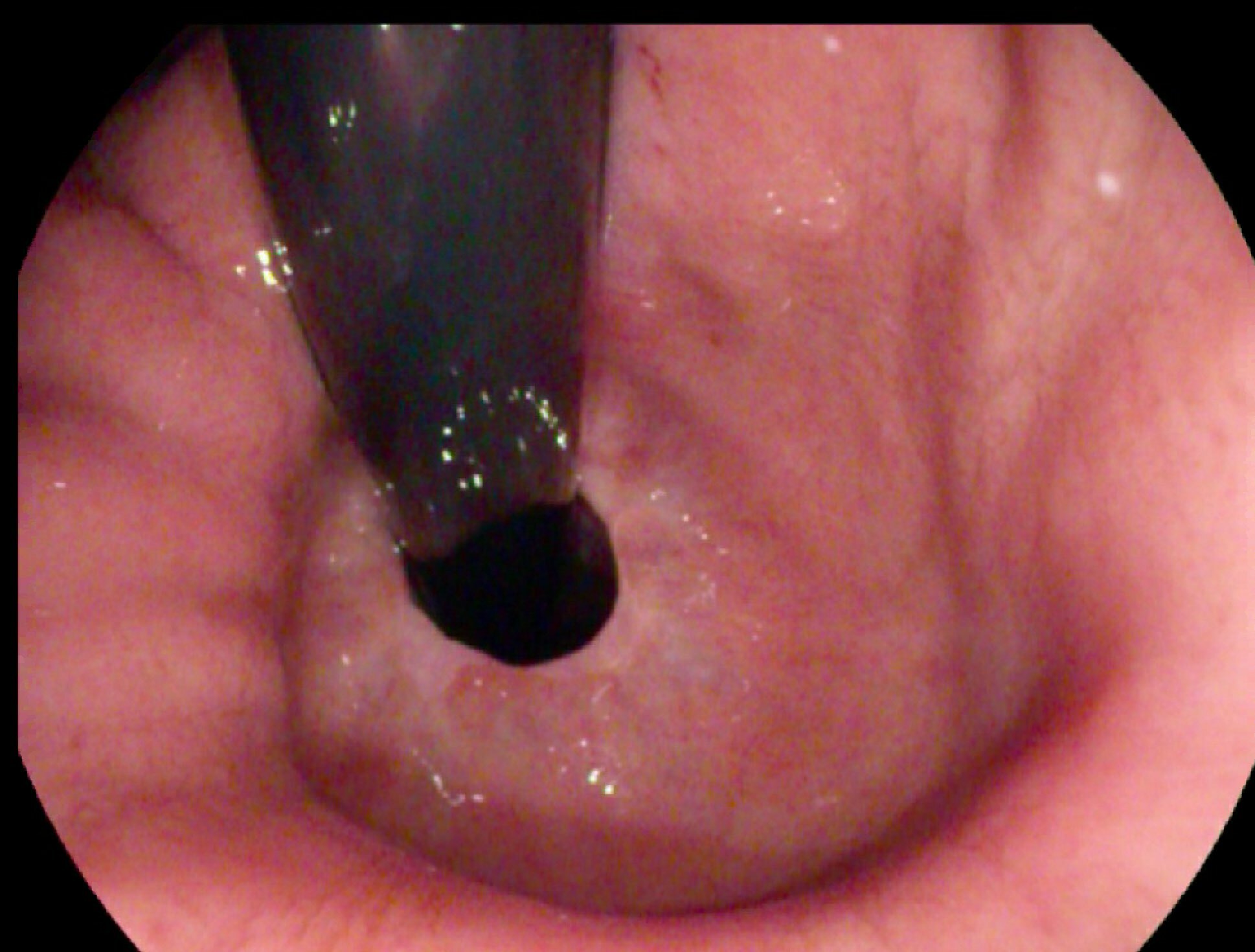

Upper GI endoscopy

A type I (sliding) hiatus hernia is observed as a >2 cm separation between the z-line and the diaphragmatic impression. A para-oesophageal hernia may be observed as a portion of the stomach herniating through the diaphragm adjacent to the endoscope.

Sliding hiatus hernia is seen on retroflexion

Barium swallow

This involves swallowing barium contrast and observing it travel down the tubular oesophagus and into the stomach. A >2 cm separation between the Z-line (identified by an area known as the B ring) and the diaphragmatic hiatus is consistent with a sliding hiatus hernia. Para-oesophageal hernias will be seen as a displacement of part of the stomach above the diaphragm with or without displacement of the GOJ (depends on type).

Type II hiatus hernia on barium swallow (grey star shows herniated fundus)

Image courtesy of Hellerhoff, Wikimedia commons

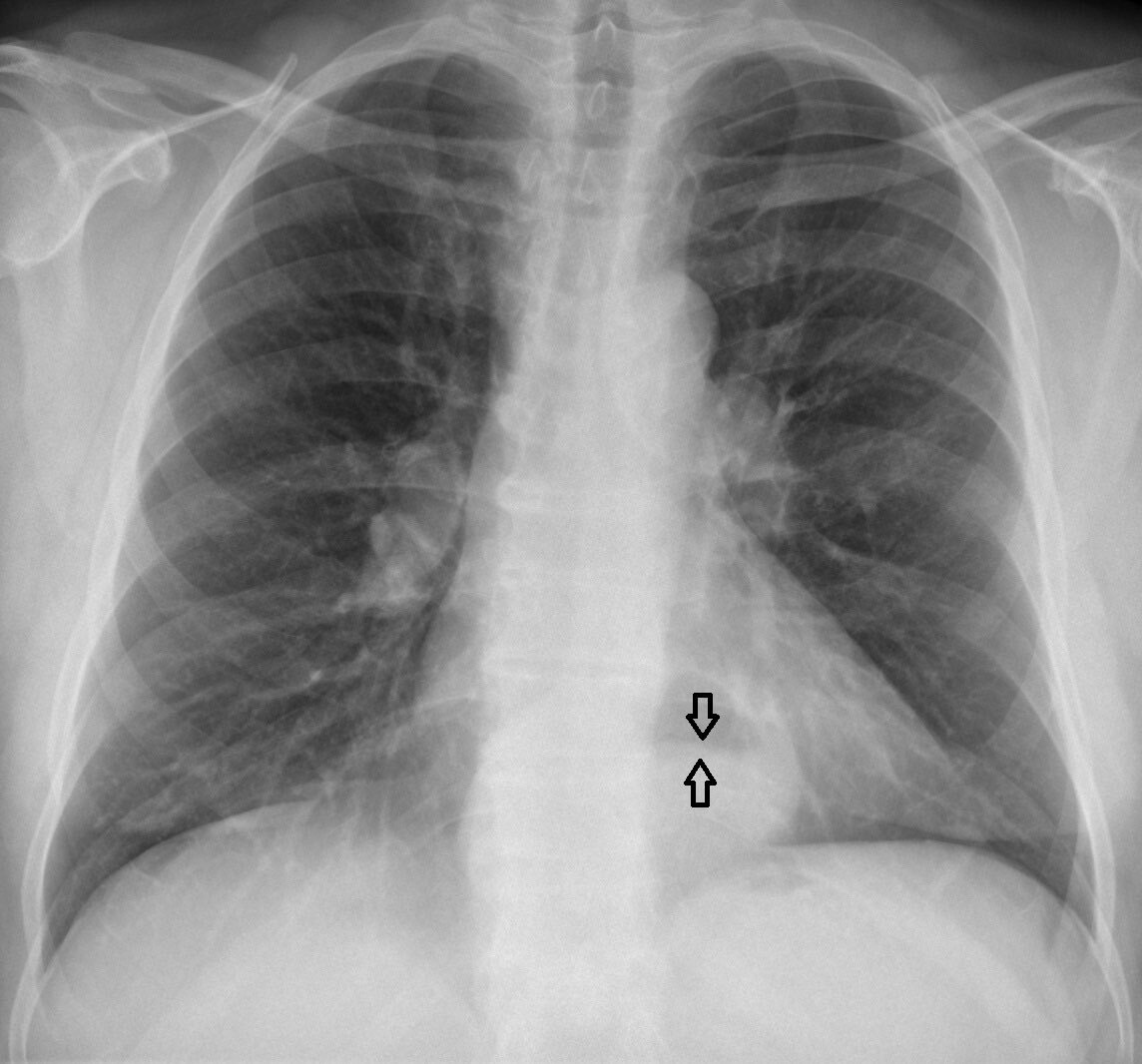

X-ray

Hiatal hernias may be seen on chest x-ray as a retrocardiac mass with or without an air-fluid level. Very large hiatal hernias may give strange appearances on X-rays due to air-fluid levels.

Type I hiatus hernia on chest x-ray (arrows show air-fluid level)

Image courtesy of Hellerhoff, labeled by Mikael Häggström, Wikimedia commons

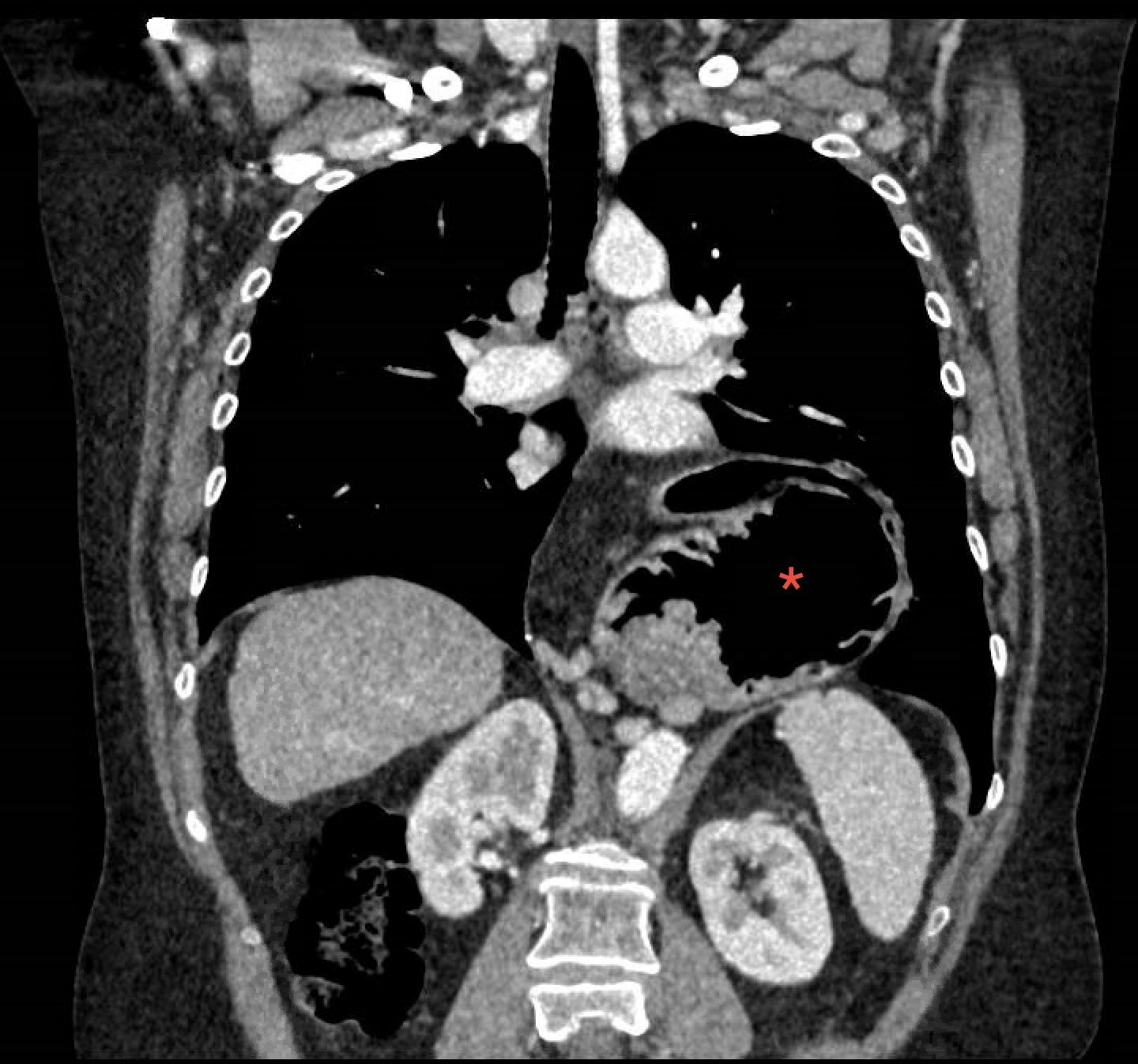

Computed tomography

CT is not conventionally completed for a hiatus hernia unless there is a suspected complication (e.g. gastric volvulus). A hiatus hernia will appear as a retrocardiac mass with or without an air-fluid level.

Large type III hiatus hernia on CT (red arrow) that is twisted on its axis

Management

The majority of hiatal hernias do not require any intervention.

The management of a hiatus hernia depends on the type and any associated complications. As a general rule, asymptomatic type I hiatal hernias do not require any intervention. Patients with symptomatic type I hiatal hernias require management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, which includes proton pump inhibitors and in highly selected cases surgery.

In patients with para-oesophageal hernias (Type II-IV), surgical intervention is typically recommended if they are symptomatic or develop complications (e.g. gastric volvulus, strangulation). There are various approaches for surgical repair that can be used (e.g. transabdominal or transthoracic para-oesophageal hernia repair).

Complications

Complications of a type I hiatus hernia are rare and typically related to the degree of reflux.

Complications in patients with a type I hiatus hernia are rare. If they do occur, they are typically related to the degree of reflux and can include erosive oesophagitis, stricture formation, and Barrett’s oesophagus.

Complications are more likely to occur in patients with para-oesophageal hernias. These may include:

- Gastric volvulus

- Strangulated hernia

- Uncontrolled bleeding

- Respiratory compromise

- Gastric outlet obstruction

- Perforation

Last updated: August 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback