Anaemia overview

Notes

Definition

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines anaemia by the following haemoglobin (Hb) concentrations:

- Males < 130 g/L (130-175 g/L)

- Females < 120 g/L (120-155 g/L)*

* In pregnancy, a Hb < 110 g/L is diagnostic.

Strictly speaking, anaemia is defined as a reduction in circulating red blood cell mass. However, in clinical practice, anaemia is defined by more measurable variables such as:

- Red blood cell (RBC) count

- Haemoglobin (Hb) concentration

- Haematocrit

Hb concentration is commonly used in the assessment of anaemia. It is important to understand that anaemia is a manifestation of an underlying problem, not a diagnosis in itself. Its recognition warrants further investigation to establish the underlying cause.

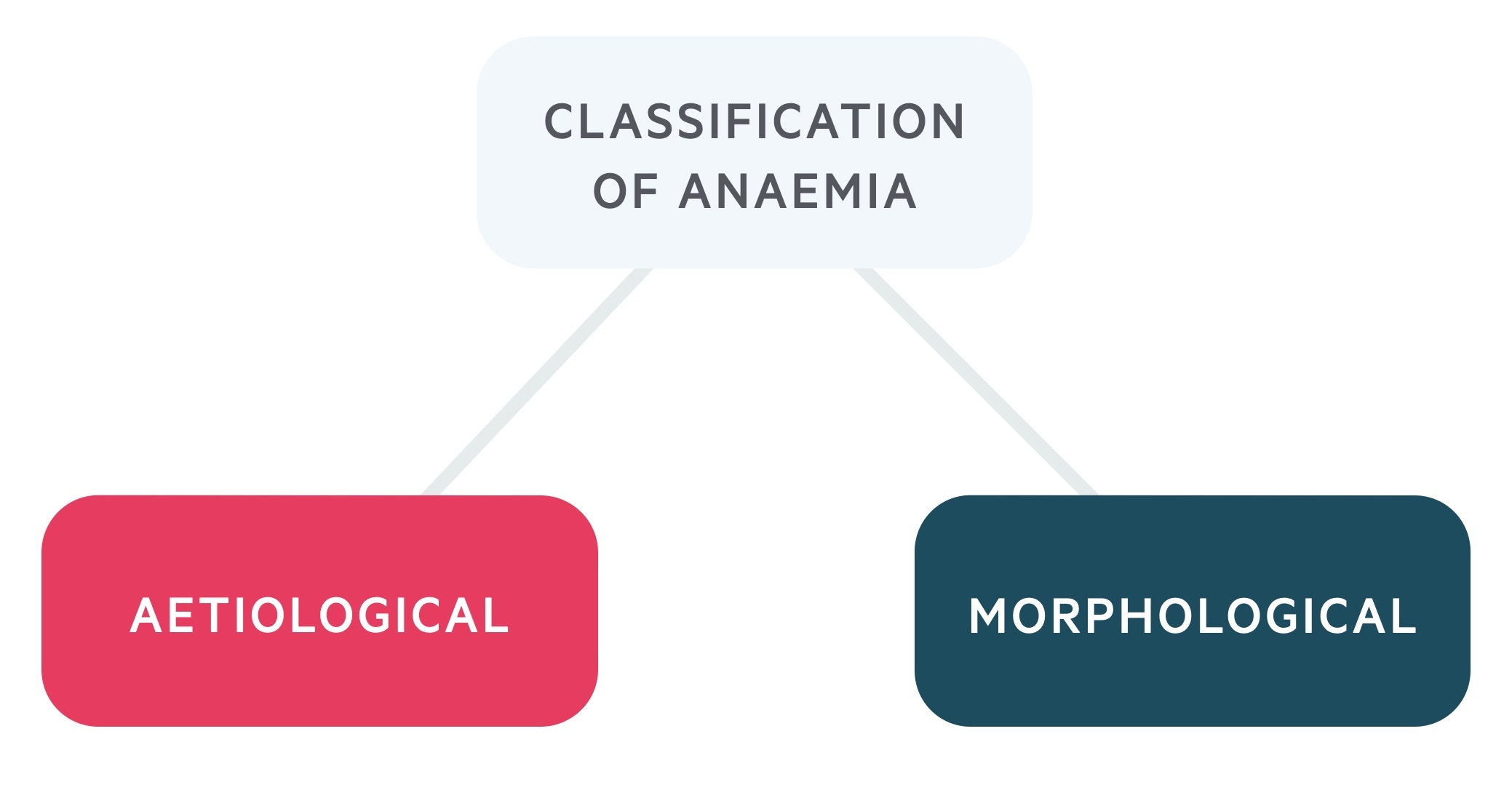

Classification

Causes of anaemia can be classified based upon aetiology or morphology.

Aetiological

The aetiological approach addresses the underlying mechanism leading to the reduction in Hb concentration.

Aetiologically, causes can be arranged into three groups:

- Decreased RBC production

- Increased RBC destruction

- Blood loss

Morphological

The morphological approach categorises anaemia based on the size of RBCs (e.g. the mean corpuscular volume).

This approach arranges anaemia into three groups:

- Microcytic (small RBCs)

- Normocytic (normal sized RBCs)

- Macrocytic (large RBCs)

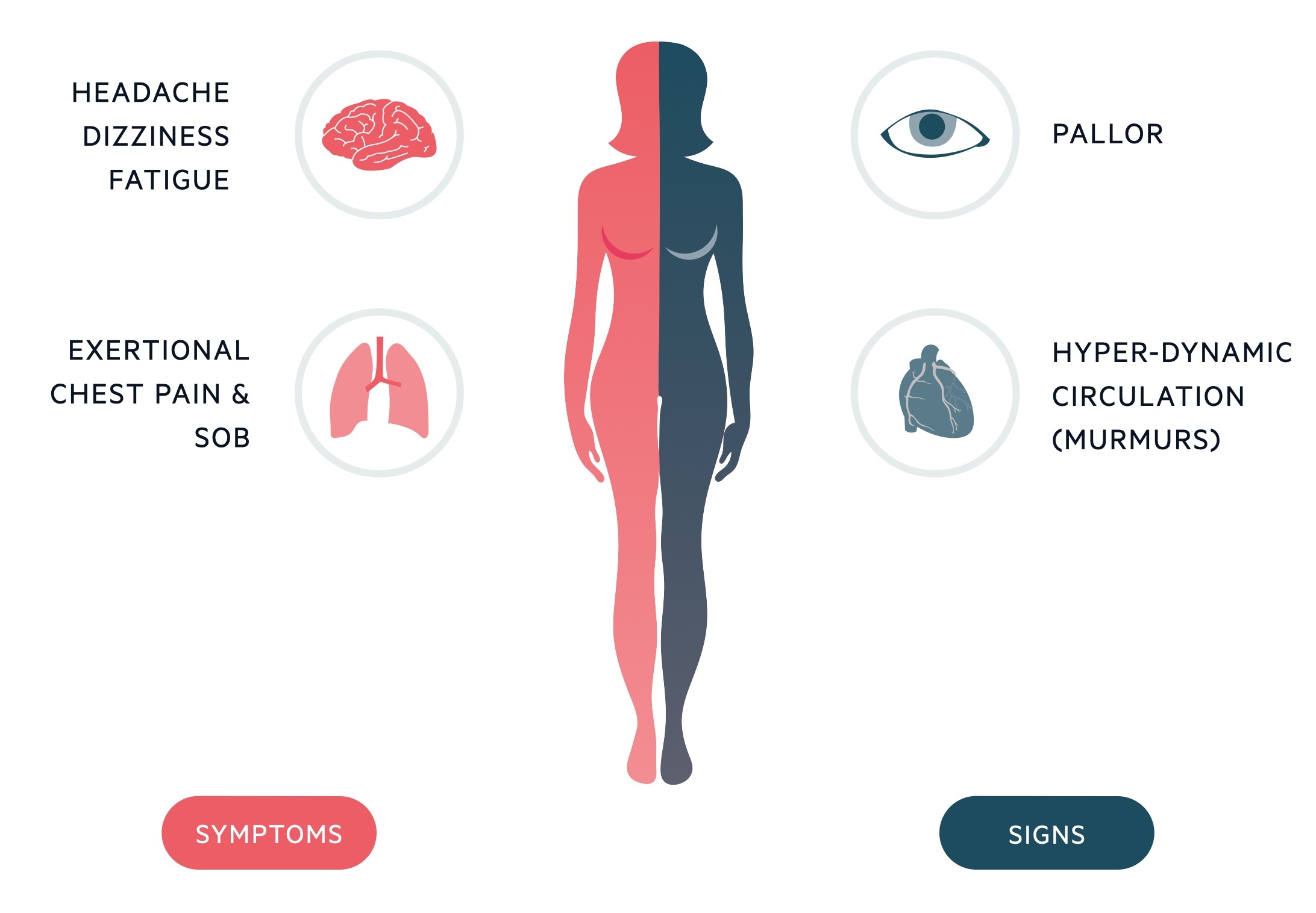

Clinical features

Clinical features are dependent on the absolute degree of anaemia & rate of decline in Hb concentration.

Patients with a sudden drop in Hb will generally be more symptomatic than patients with a gradual decline in Hb concentration.

The clinical features associated with anaemia reflect a reduction in oxygen delivery. In cases of acute blood loss, the signs and symptoms of hypovolaemic shock may be present.

Symptoms

- Dyspnoea

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Syncope

- Confusion

- Palpitations

- Angina

Signs

- Bounding pulse

- Postural hypotension

- Tachycardia

- Conjunctival pallor

- Shock

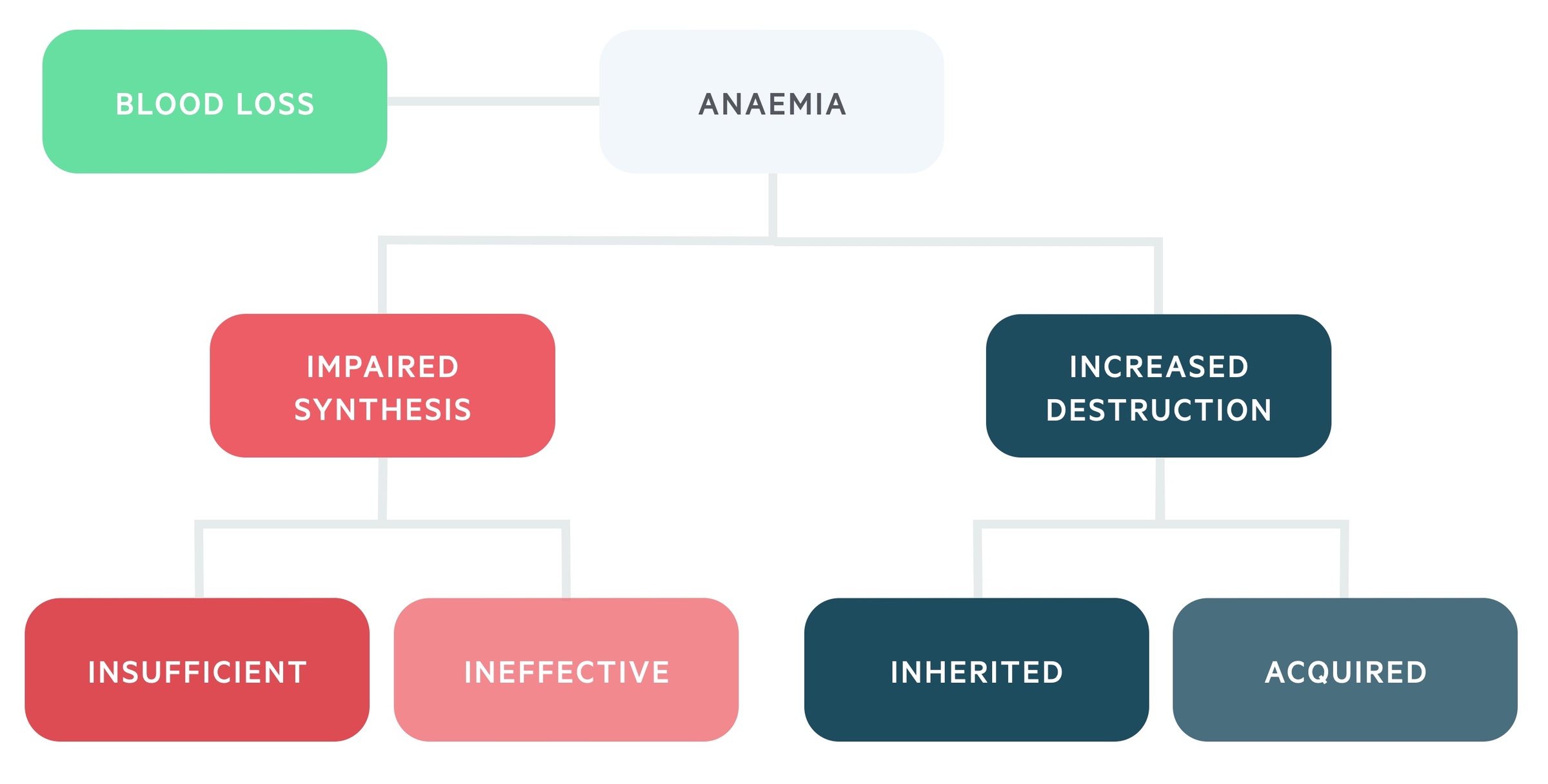

Aetiological classification

Classifies the causes of anaemia based upon the underlying mechanisms.

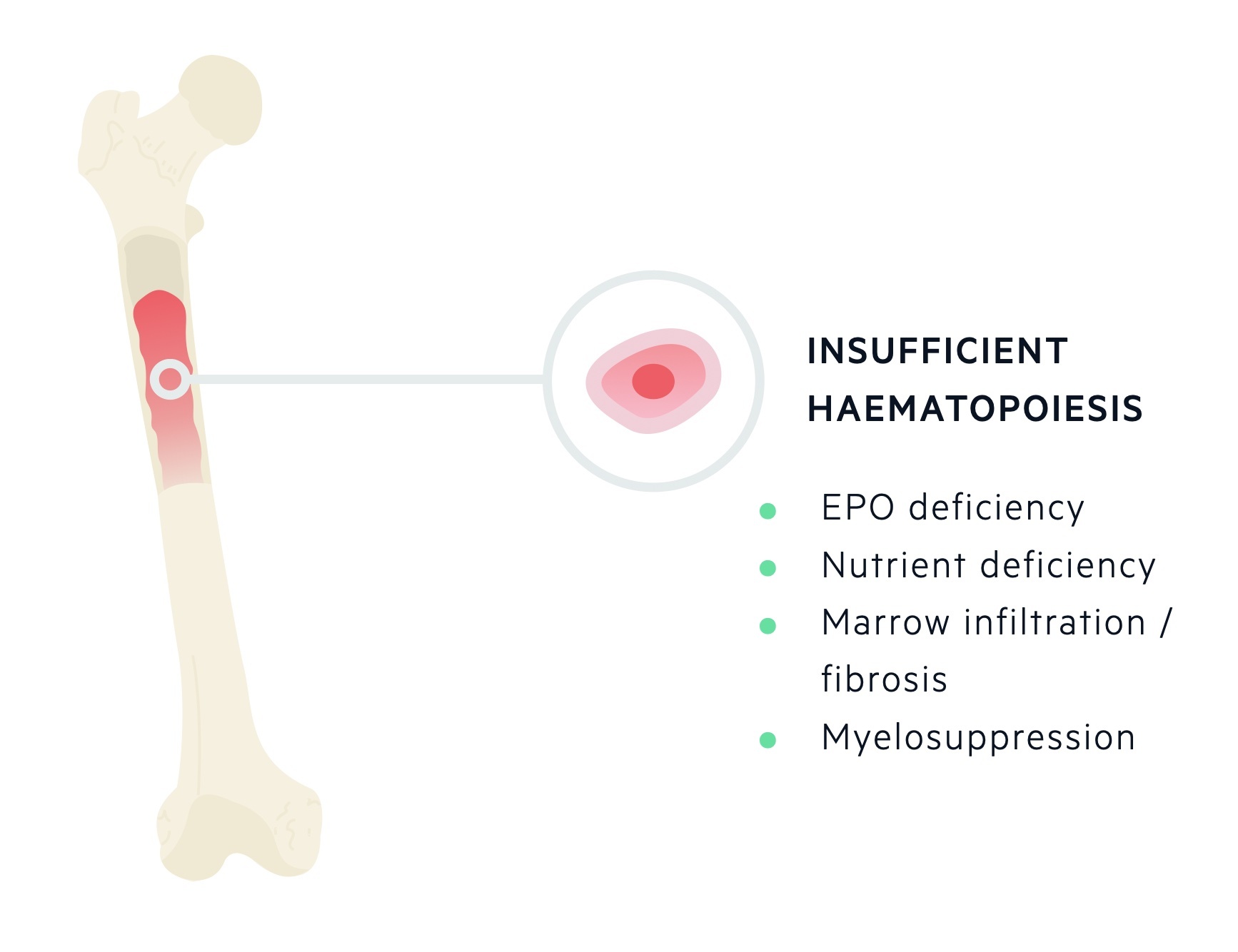

Impaired synthesis

Anaemia will develop if the rate of RBC production does not adequately meet the bodies requirements.

A decrease in RBC production can occur due to two main mechanisms:

- Insufficient production of RBCs

- Ineffective production of RBCs

Insufficient production of RBCs occurs when the normal erythropoietic process is reduced or inhibited. This may be due to a lack of required nutrients (e.g. iron), reduced hormonal influence (e.g. low EPO, hypothyroid), bone marrow suppression or bone marrow infiltration.

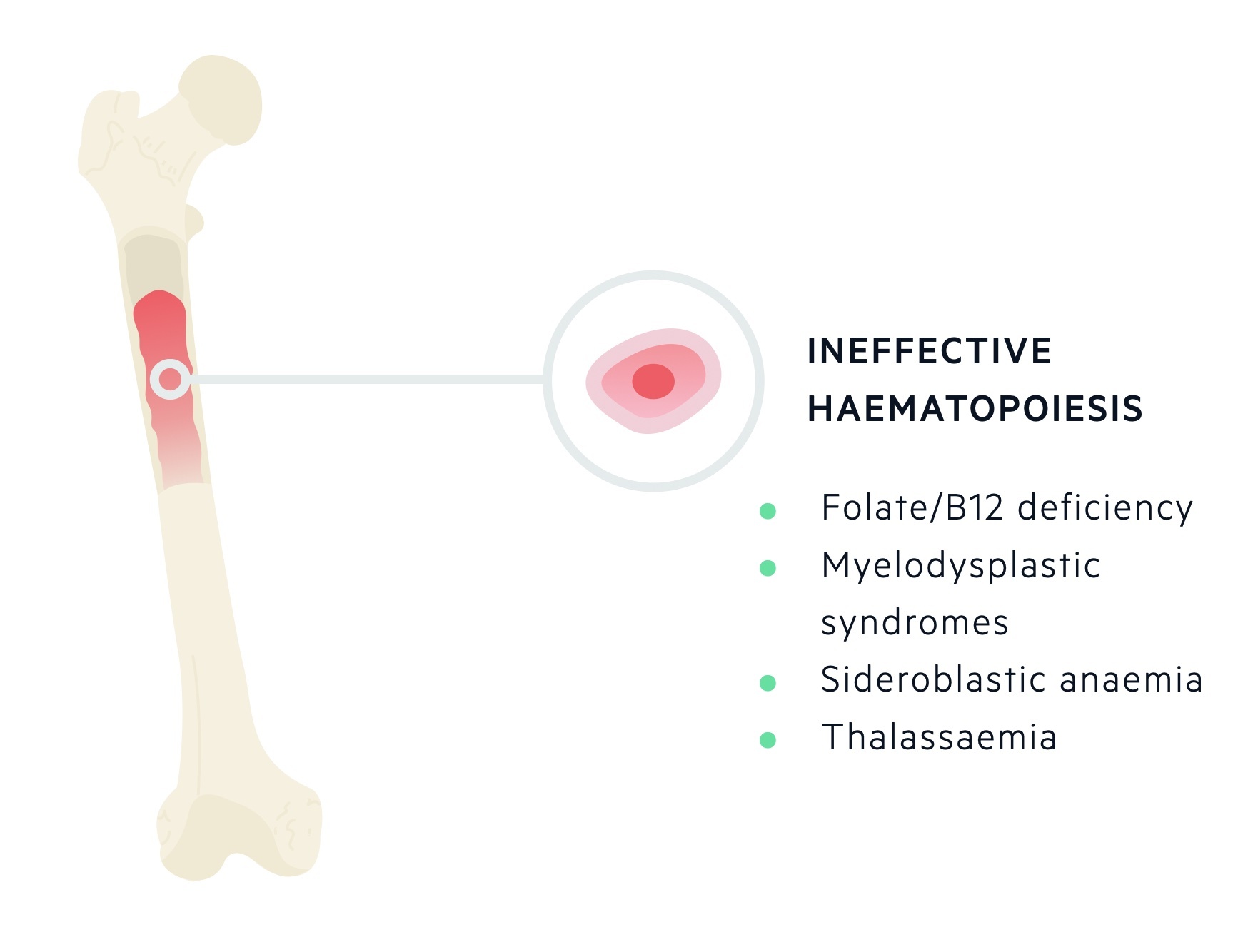

Ineffective production of RBCs occurs due to abnormal erythropoiesis. There is a marked increase in the erythroid cell line in the bone marrow, but erythroid precursors do not mature properly and subsequently undergo apoptosis. Conditions that lead to ineffective erythropoiesis include megaloblastic anaemias (e.g. folate and B12 deficiency), thalassaemias, myelodysplastic syndromes and sideroblastic anaemia.

Increased destruction

Haemolysis refers to the destruction of red blood cells, which is broadly defined as a reduction in the lifespan of RBCs below 100 days (normal 110-120 days).

If RBC production in the bone marrow cannot keep pace with the level of haemolysis, then haemolytic anaemia with ensue. The haemolytic anaemias can be divided into inherited and acquired.

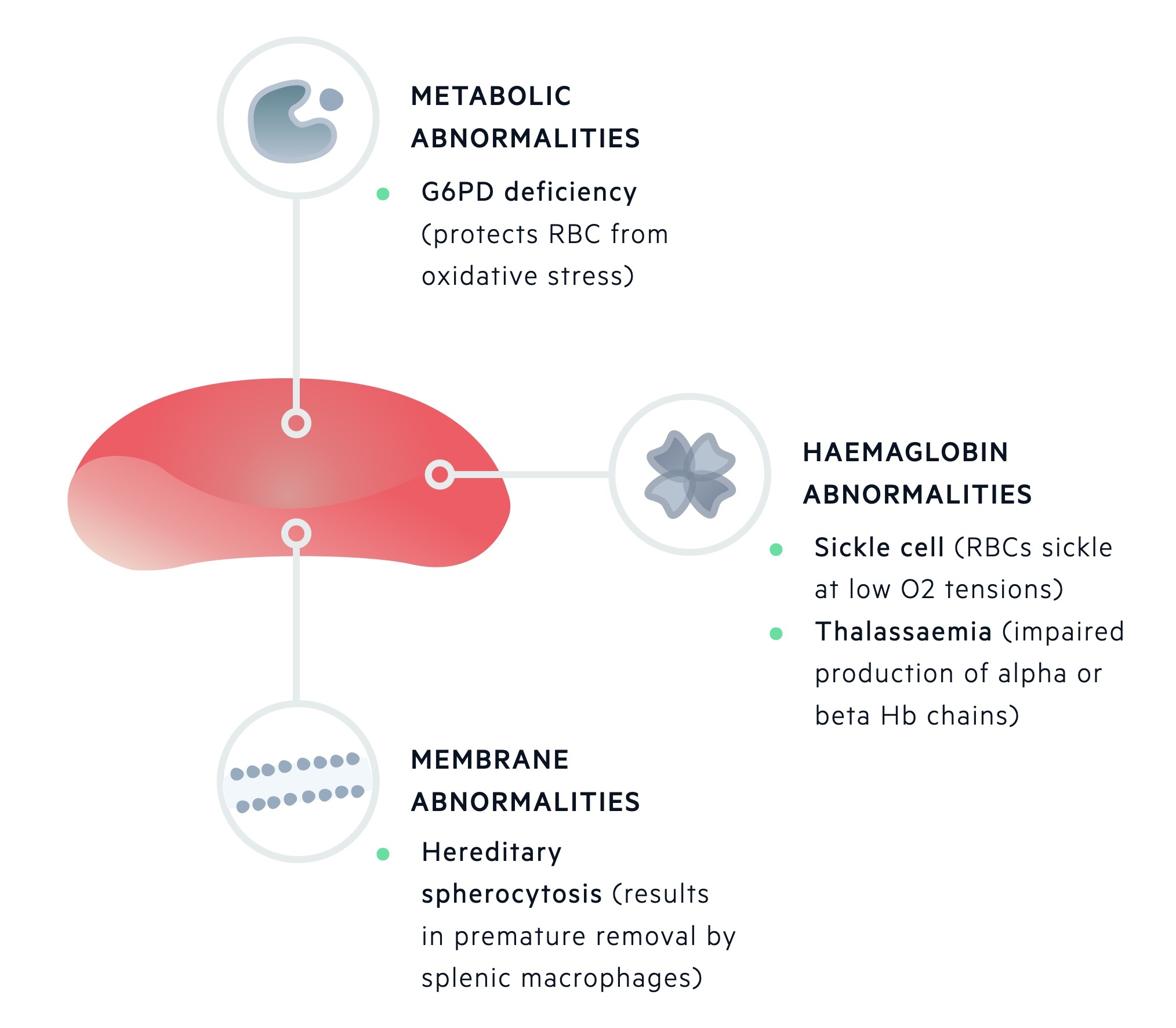

Inherited haemolytic anaemias can be further classified based on the site of inherited defect:

- Membrane abnormalities (e.g. hereditary spherocytosis)

- Metabolic deficiencies (e.g. G6PD deficiency)

- Haemoglobin abnormalities (e.g. alpha-thalassaemia, beta-thalassaemia, sickle cell disease)

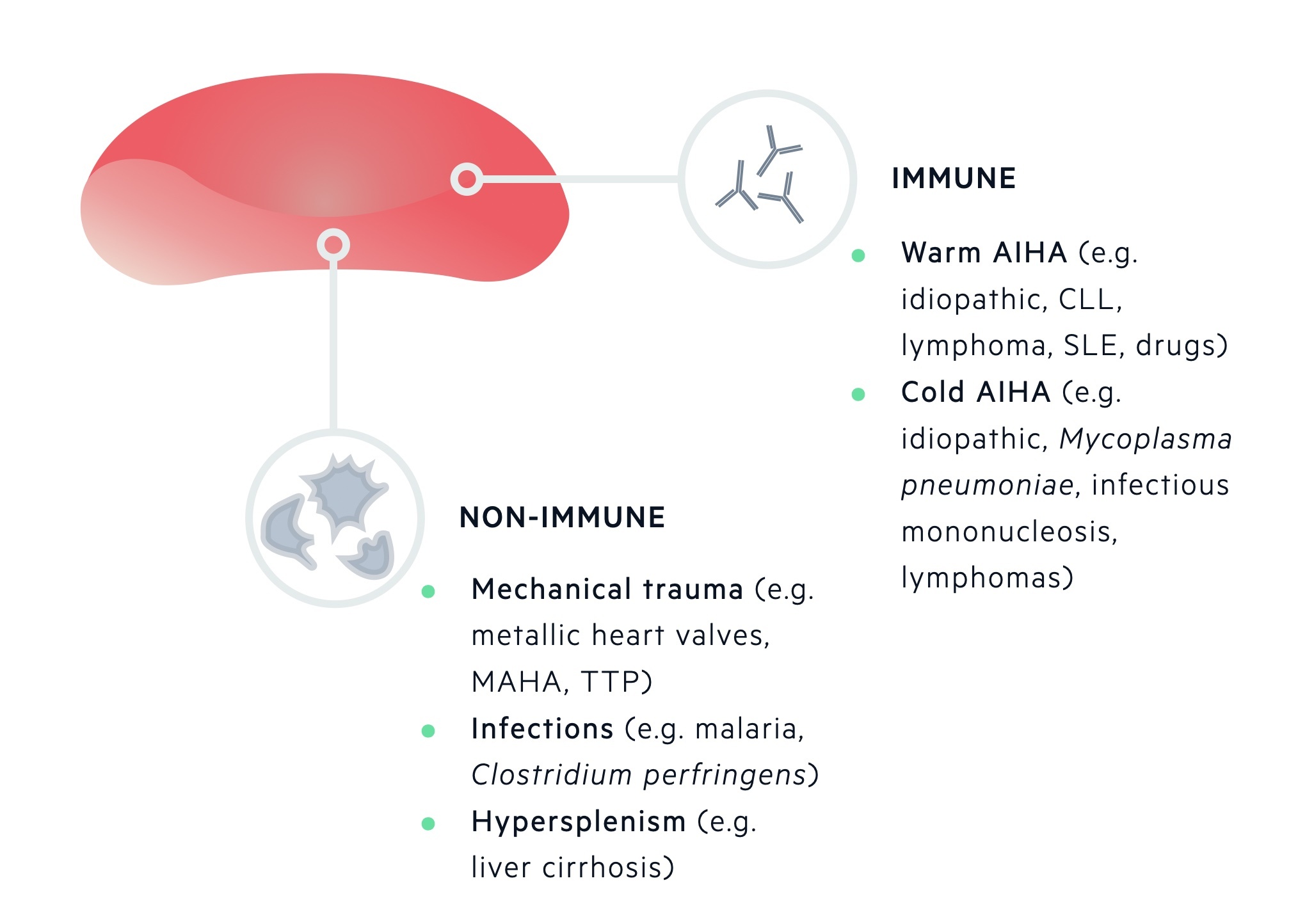

Acquired haemolytic anaemias can be divided into immune and non-immune:

- Immune (e.g. warm and cold autoimmune haemolytic anaemia)

- Non-immune (e.g. mechanical trauma, hypersplenism, infections, drugs)

Blood loss

Blood loss is a common cause of anaemia, it may be obvious (e.g. trauma, haematemesis) or occult (e.g. gastrointestinal malignancy).

Erythrocytes form a major store of iron within the body. This means a loss of erythrocytes could lead to the development iron deficiency anaemia (IDA). Consequently, IDA commonly reflects blood loss from an unidentified source that requires further investigation.

Two common sources of blood loss include menstruation in young females and gastrointestinal bleeding in older populations.

Morphological classification

Classifies the causes of anaemia based upon the mean corpuscular volume (MCV).

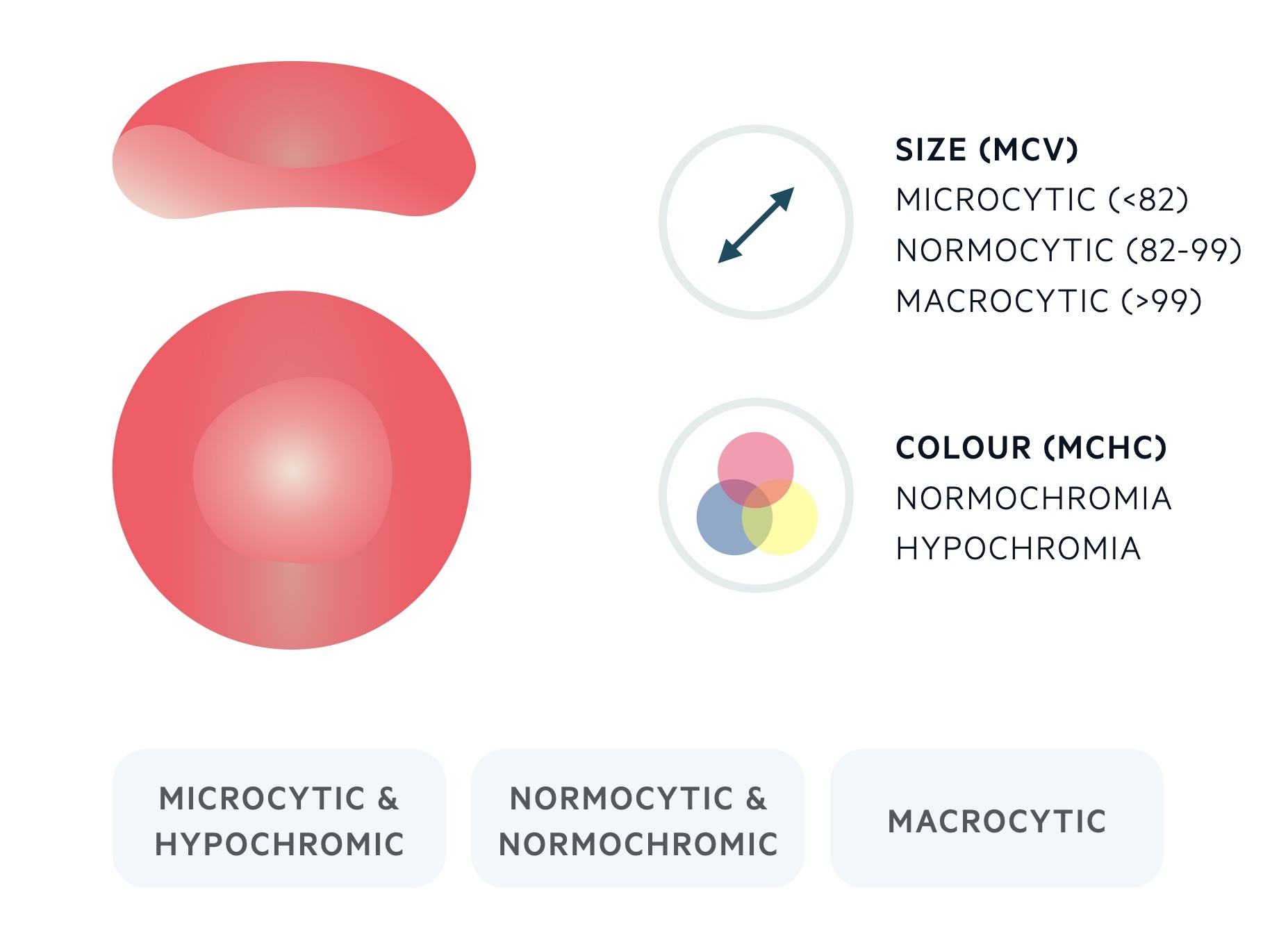

The MCV is a measure of the average volume of a RBC. The MCV is measured in femtolitres (fL) and usually resides between 82 and 99. RBCs that are > 99 fL are referred to as macrocytes, RBCs that are < 82 fL are referred to as microcytes. A normal RBC is approximately 7 microns in diameter.

Microcytic

Anaemia is described as microcytic when the MCV is < 82 fL.

Microcytic anaemia is commonly associated with a reduction in the mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC), which leads to the appearance of pale (hypochromic) RBCs.

The most common cause of microcytic anaemia is iron-deficiency anaemia (IDA). This may be evaluated with iron studies (transferrin and serum iron) and serum ferritin.

Other important causes of microcytic anaemia include:

- Anaemia of chronic disease (predominantly causes normocytic anaemia)

- Thalassaemia

- Other haemoglobinopathies

- Lead poisoning

- Sideroblastic anaemia

Normocytic

Anaemia is described as normocytic when the MCV is within normal limits (82-99 fL).

The causes of normocytic anaemia are extremely broad and it may reflect the early stages of either a microcytic or macrocytic anaemia.

Anaemia may be the first manifestation of a systemic disorder. One of the most common causes of a normocytic anaemia is ‘anaemia of chronic disease’.

Other common causes of a normocytic anaemia include blood loss, renal disease, cancer-associated anaemia and pregnancy.

Macrocytic

Anaemia is described as macrocytic when the MCV is > 99 fL.

There are numerous causes of a macrocytic anaemia, but it is commonly secondary to folate and/or B12 deficiency. Folate and B12 deficiency cause a megaloblastic (immature) macrocytic anaemia and abnormal nucleic acid metabolism.

Drugs that interfere with nucleic acid metabolism may also cause a macrocytic anaemia (e.g. methotrexate).

Other important causes of a macrocytic anaemia include:

- Alcohol abuse

- Liver disease

- Hypothyroidism

- Haematological malignancies

- Reticulocytosis

Last updated: October 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback