Chronic myeloid leukaemia

Notes

Introduction

Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) is a clonal myeloproliferative neoplasm characterised by abnormal clonal expansion of cells of the myeloid lineage.

Leukaemia

Leukaemia refers to a group of malignancies that arise in the bone marrow. They are relatively rare but together are the 12th most common cancer in the UK, responsible for around 4,700 deaths a year.

There are four main types:

- Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)

- Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL)

- Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL)

Presentation, prognosis and management all depend on the type and subtype of leukaemia.

Chronic myeloid leukaemia

The condition is characterised genetically by the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome, an abnormal chromosome 22 that results in a constitutively activated tyrosine kinase.

The expansion of abnormal granulocytes leads to the replacement of normal myeloid tissues. Survival has improved dramatically with the introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Epidemiology

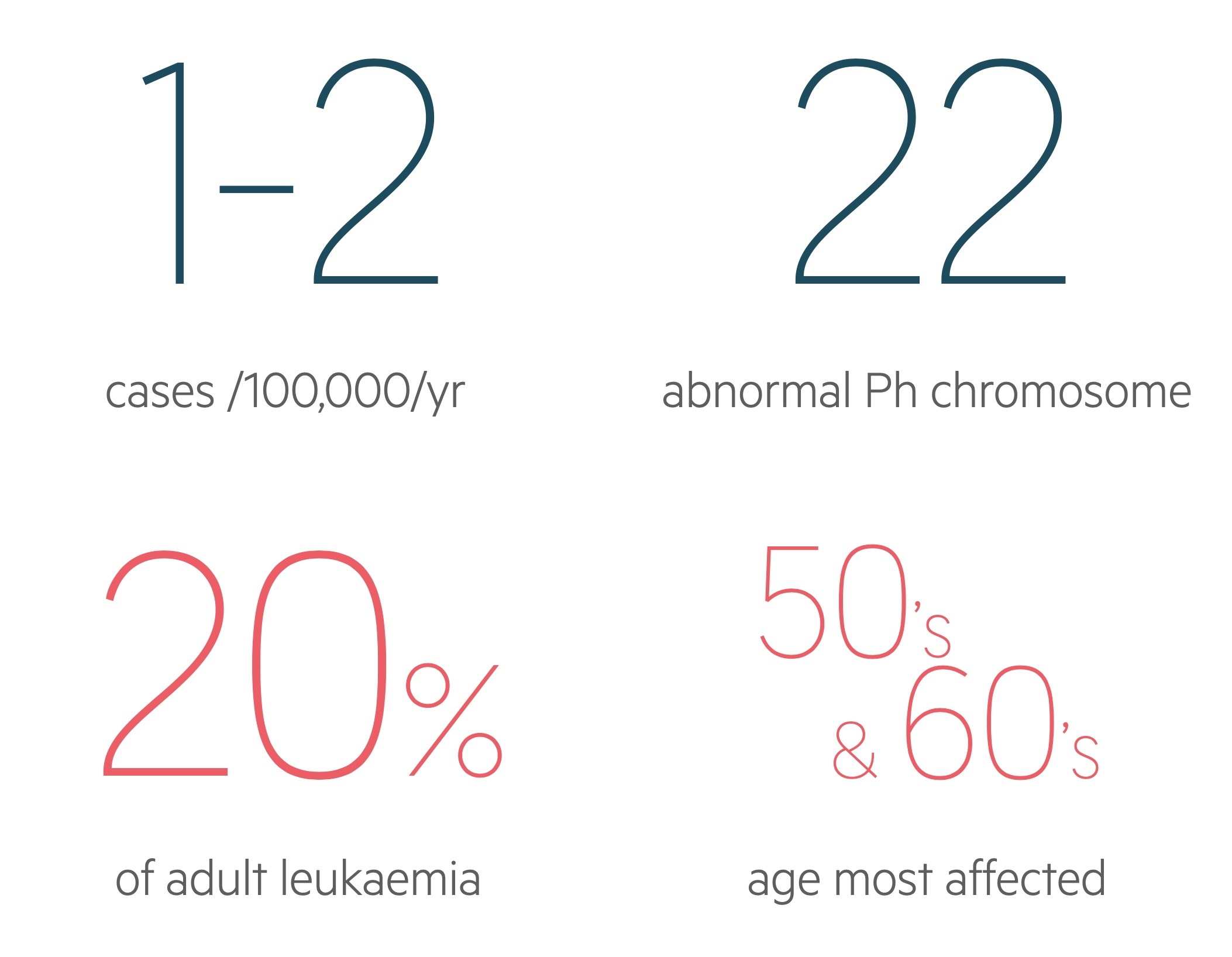

CML has an annual incidence of 1-2 cases per 100,000.

The condition is slightly more common in men. It can occur at any age, is rare in children, and often presents in the 50’s and 60’s in the western world.

It accounts for around 15-20% of leukaemia cases in adults

Genetics

The hallmark cytogenetic finding in CML is the Ph chromosome.

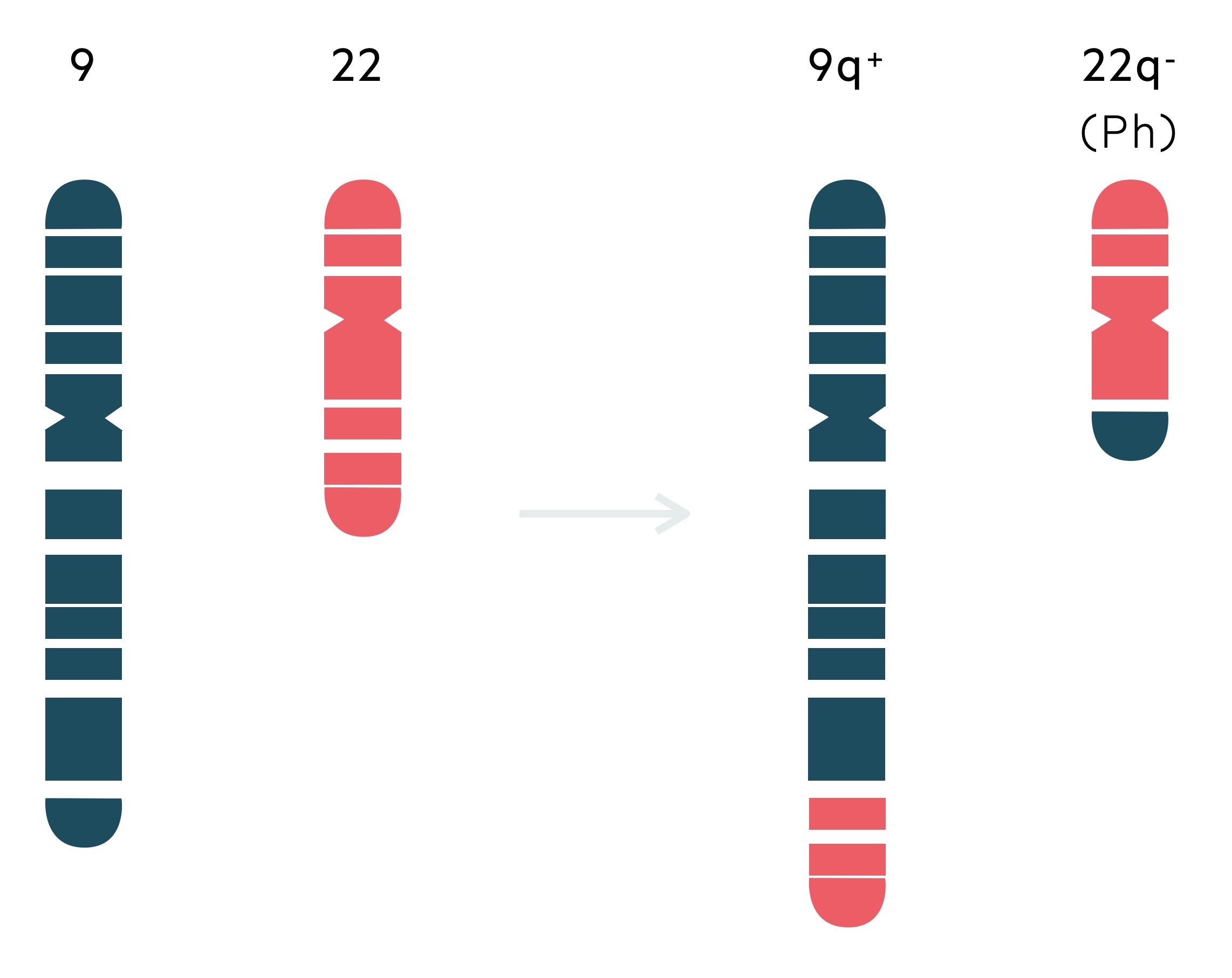

The Ph chromosome was as first identified by David Hungerford and Peter Nowell in 1959, by observing a short chromosome 22 in two patients with CML. It was not until the 1970's that Janet Rowley, a geneticist, demonstrated the abnormality was secondary to a reciprocal translocation.

A reciprocal translocation refers to a rearrangement where parts of two chromosomes are exchanged. The Ph chromosome, an abnormal chromosome 22, results from a reciprocal translocation between chromosome 9 and chromosome 22 - t(9;22)(q34;q11). Cytogenetic analysis identifies the Ph chromosome in 95% of patients with CML at diagnosis.

The abnormal chromosome 22 is characterised by the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene that encodes for the BCR-ABL1 protein - a constitutively activated tyrosine kinase.

NOTE: Ph chromosome is not found via conventional means in around 5% of cases. This may result from variant or cryptic translocations.

Clinical features

CML often presents with non-specific symptoms like fatigue, weight loss and night sweats.

Around 20-40% are asymptomatic and picked up incidentally during investigations (FBC) for other reasons. Splenomegaly is common, seen in at least 40- 50% of patients at diagnosis (and more in some research cohorts). Symptoms most commonly result from overall disease burden, anaemia and splenomegaly. This results features like fatigue, weight loss, abdominal discomfort and early satiety.

Other symptoms may be caused by thrombocytopenia or leucostasis but these are far less common. Features indicative of tissue infiltration (outside the spleen and liver) like bone pain, lymphadenopathy, skin infiltration and extramedullary masses are rare and seen in advanced phase disease.

Symptoms

- Fatigue

- Weight loss

- Night sweats

- Anaemia:

- Fatigue

- Breathlessness

- Angina

- Thrombocytopenia:

- Petechiae

- Nose bleeds

- Bruising

- Splenomegaly:

- Early satiety

- Abdominal pain

- Bone pain

- Leucostasis:

- Headache

- Breathlessness

- Visual changes

- Priapism

Signs

- Splenomegaly

- Hepatomegaly

- Lymphadenopathy

- Leucostasis:

- Altered mental state

- Priapism

Diagnosis & investigations

Cytogenetics allows the identification of Ph chromosome in around 95% of patients with CML.

Diagnosis is typically straightforward and consists of demonstrating characteristic blood counts and differential (excessive granulocytosis with typical left shift) and the presence of Ph chromosome.

As mentioned above, Ph chromosome is not identified on cytogenetics in around 5%. In these patients fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH) or quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) can be used to confirm the presence of BCR-ABL1 fusion.

Bloods

FBC: White cell count (WCC) are elevated in almost all patients with the differential showing marked neutrophilia. Basophils are almost always raised and eosinophils are commonly elevated. Half of patients will have a WCC above 100 x 10⁹/L. Anaemia and thrombocytosis are also often seen.

Blood film: Immature and mature myeloid cells are seen in CML. The proportion of blasts and basophils help to categorise the phase of disease.

Further tests are indicated for numerous reasons. Recording baseline organ function and identifying cardiovascular risk factors is indicated. LDH, urate and potassium can be useful markers of cell turnover.

- Renal function

- Liver function test

- Bone profile

- Magnesium

- LDH & urate

- Metabolic profile (lipids, HbA1c)

- Blood borne virus screen

Identifying Ph chromosome

Metaphase cytogenetics can be used to identify the abnormal chromosome 22. FISH or RT-qPCR can be used to confirm the presence of BCR-ABL1 fusion.

Bone marrow aspirate +/- trephine

Allows review of percentages of blasts, promyelocytes, basophils and other haematological cell types for staging of phase as well as material for cytogenetics. The proportion of blasts and basophils help to categorise the phase of disease.

The marrow tends to be hypercellular with myeloid hyperplasia in chronic phase disease (see Phase chapter below for more).

Phases

CML tends to follow three phases: chronic, accelerated and blast crisis.

1. Chronic phase

The vast majority (> 85%) present in the chronic phase of disease. Clinical features are typically non-specific and include fatigue, weight loss and night sweats. Prior to advanced treatment options this phase would tend to last 3-5 years.

2. Accelerated phase

In the accelerated phase symptoms and features become more apparent and severe. Disease is more difficult to treat and outcomes worse. Untreated this phase lasts around 6-18 months, though in some patients there is no identifiable accelerated stage.

It has various definitions the main being from European LeukemiaNet (ELN) and the World Health Organisation. Below is the ELN definition:

- Blasts in blood or marrow 15–29%, or blasts plus promyelocytes in blood or marrow >30%, with blasts <30%

- Basophils in blood ≥20%

- Persistent thrombocytopenia (<100 × 109/L) unrelated to therapy

- Clonal chromosome abnormalities in Ph+ cells, major route, on treatment

3. Blast crisis

This phase resembles an acute leukaemia with the rapid expansion of blasts. Without treatment survival is typically a few months. It is defined by ELN as:

- Blasts in blood or marrow ≥30%

- Extramedullary blast proliferation, apart from spleen

Management

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI's) are central to the treatment of CML.

The treatment of CML (as is the case with all haematological malignancies) is enormously complex and dependent on phase at diagnosis, exact BCR-ABL1 mutations and patient factors amongst other considerations.

At an undergraduate level a general understanding of the treatment options is sufficient - those interested in more detail see our further reading section. There are three major classes of treatment:

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors: these drugs have completely transformed the management of CML. They directly inhibit tyrosine kinase - blocking the enzyme created by the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene.

- Intensive chemotherapy: typically reserved for patients with blastic transformation - treatment is based on that which is given for AML. Significant side-effects and patients must be fit for such therapy.

- Allogenic stem cell transplantation: may be used in chronic phase patients who have failed other treatment options or for patients with advanced phase disease.

The introduction of TKI’s have revolutionised the treatment of CML. It forms the first-line therapy for essentially all new cases of CML. There are three TKI’s approved for first-line therapy:

- Imatinib: a first-generation TKI. Still commonly used, a standard dose is a single 400mg tablet daily. Side effects include nausea & vomiting, oedema, cramps, rashes, GI symptoms, headache and fatigue.

- Dasatinib: a second-generation TKI that has activity against a number of imatinib resistant BCR-ABL1 variants. General side effects are similar to those described above for imatinib. Can cause pleuro-pulmonary toxicity - and is generally avoided in those with pre-existing pleural, pulmonary or pericardial disease.

- Nilotinib: a second-generation TKI that has activity against a number of imatinib resistant BCR-ABL1 variants. Side effects include cytopenias, headache, nausea, change in bowel habit, rash, pruritus, fatigue and derangement of LFTs. There is a significant increase in cardiovascular events and it may cause prolonged QT.

Chronic phase

Emergency cytoreduction may be needed in patients with very elevated WCC at diagnosis (e.g. > 100 ×109/L). Good oral hydration and allopurinol may be needed to reduce the risk of tumour lysis syndrome.

Three TKI’s are approved for first-line treatment of chronic phase CML; imatinib, dasatinib and nilotinib. Patients who demonstrate treatment failure with or are not tolerant of first-line therapies, are normally offered an alternative first or second-line TKI. Second generation TKI’s - dasatinib, nilotinib or bosutinib - are used. Another TKI - ponatinib (a third generation TKI) - may be used in patients with specific mutations.

Allogenic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT) may be considered in patients who have failed initial treatment options - typically due to treatment resistance or intolerance.

Advanced phase

Treatment is more challenging in patients in accelerated phase or blast crisis. Ideally all patients should be treated as part of a clinical trial.

Management depends on whether patients are in the accelerated phase or have undergone blastic transformation and whether this occurred de-novo or during treatment for chronic phase disease. In general it involves a second generation TKI with or without intensive chemotherapy.

Allo-SCT offers potential cure in appropriate patients and may be used following the above management or as initial therapy (particularly if CML progresses during treatment for chronic phase disease).

Prognosis

Patients with newly-diagnosed chronic phase CML and access to the advanced healthcare have a near-normal life-expectancy.

The prevalence of CML is increasing as survival continues to improve. Those with treatment resistant or advanced phase disease still have poorer outcomes. As TKI's are relatively new many long-term studies are still returning results.

Figures from Cancer Research UK show:

- Ages of 15-64: 90% 5-year survival

- 65 and older: 40% 5-year survival

Co-morbidities and toxic treatment effects are now increasingly relevant and require optimisation of modifiable risk factors and treatment regimens to optimise outcomes.

Further reading

For those interested in further detail on the diagnosis and management of CML see the links below.

- European LeukemiaNet: Recommendations for treating chronic myeloid leukemia, 2020

- European Society for Medical Oncology: Chronic myeloid leukaemia: ESMO Clinical PracticeGuidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up, 2019

- Pan-London Haemato-Oncology Clinical Guidelines: Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia, 2020

Last updated: July 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback