Transfusion reactions

Notes

Overview

Transfusion Reactions are a spectrum of reactions to blood components.

Transfusion reactions can vary from mild fever to life-threatening, systemic reactions.

Definitions

“Blood Product”

An umbrella term which includes both:

- Blood Components

- Plasma Derivatives (i.e. products manufactured from pooled plasma donations)

Plasma derivatives include many substances such as albumin, clotting factors, and immunoglobulins.

“Blood Component”

A more specific description, which refers to specific parts (or ‘components’) of whole blood (e.g. red cells, pooled platelets, fresh frozen plasma, and cryoprecipitate).

In this article, we will look at reactions to blood components, otherwise known as 'transfusion reactions'.

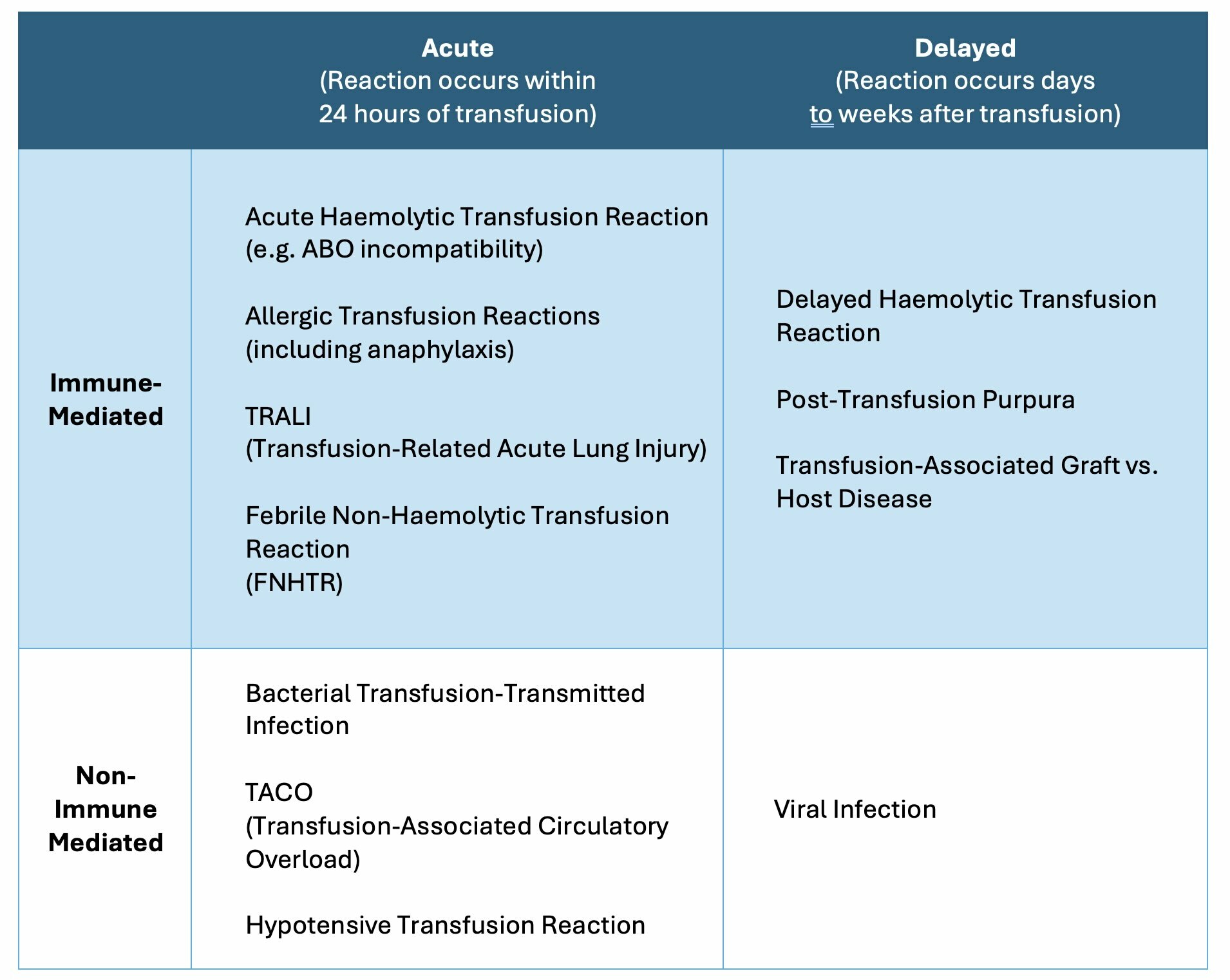

Classification

Transfusion reactions can be classified into different groups.

The different types of transfusion reactions are usually classified in two ways:

- Whether the reaction is Acute or Delayed

- Whether the reaction is Immune-Mediated or Non-Immune Mediated

Acute transfusion reactions

In the hospital setting, as a non-specialist healthcare professional, you are more likely to encounter acute transfusion reactions.

In the following sections, we will discuss the aetiology, pathophysiology, clinical features, and management of acute transfusion reactions. Acute transfusion reactions can be fatal without rapid assessment and management so all healthcare professionals must understand how to recognise and manage these types of reactions.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

The most serious type of Transfusion Reaction is due to the transfusion of ABO-incompatible red cells.

There are several types of acute transfusion reactions and each have different underlying mechanisms.

Acute haemolytic transfusion reaction

The most serious type of Acute Haemolytic Transfusion Reaction is due to the transfusion of ABO-incompatible red cells.

All patients possess antibodies to A and B red cell antigens which are not usually present in their own blood. For example, a patient with Type O blood will possess antibodies to both A and B red cell antigens. As one example, if a patient with Type O blood is given a transfusion of Type A blood, there will be rapid antibody-mediated destruction of the transfused red cells. This destruction takes place within blood vessels, and is termed ‘intravascular haemolysis’. Transfusion of as little as 30ml of Group A red blood cells to a Group O patient has been fatal.

Acute Haemolytic Transfusion Reactions are usually the result of error(s), resulting in the wrong patient receiving the wrong blood.

Allergic Transfusion Reactions (Including Anaphylaxis)

Allergic transfusion reactions are type 1 hypersensitivity reactions – this means they involve IgE antibodies interacting with antigens. This can happen in one of two ways:

- Soluble antigens in the donated blood component are targeted by recipient IgE antibodies.

- IgE antibodies in the donated blood component target antigens in the recipient.

Allergic transfusion reactions vary widely in severity. They range from mild allergy symptoms (pruritis, hives, urticaria, or localized angioedema) up to full-blown anaphylaxis (with wheeze, hypotension and systemic angioedema).

TRALI (Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury)

In TRALI, antibodies in the donor blood component react with the patient’s neutrophils, monocytes, or pulmonary endothelium. This reaction leads to inflammatory cells being sequestered in the lungs. Due to pulmonary sequestration, plasma leaks out of capillaries into alveolar spaces, causing non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema (i.e. pulmonary oedema in the absence of cardia failure).

Febrile Non-Haemolytic Transfusion Reactions (FNHTRs)

The cause of FNHTRs isn’t fully understood.

It is likely that white cells present in the transfused products cause a reaction – possibly by the release of cytokines. This theory is supported by the fact that ‘leucodepletion’ (i.e. the removal of white blood cells from donated blood components) leads to a reduction in the incidence of FNHTR.

Bacterial Transfusion: Transmitted Infection

Bacteria which have gained access to blood components can be transfused to patients. Once transfused, the range of patient responses can vary from mild infective features (e.g. fever) to septic shock. Platelets are particularly prone to bacterial growth since they are stored at room temperature, rather than being cooled during storage like the other blood components.

TACO (Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload)

TACO is essentially the development of fluid overload due to the administration of intravascular volume, in this case, blood components. There are certain risk factors that put patients at an increased risk of fluid overload:

- Elderly

- Heart failure

- Renal failure

- Low albumin concentration

- Pre-existing positive fluid balance

Hypotensive Transfusion Reaction

Vasoactive substances in the donor blood (e.g. bradykinins) cause vasodilation and hypotension in recipients. Patients taking ACE inhibitors are at a higher risk.

Epidemiology

Less serious transfusion reactions are more common (e.g. mild allergic and febrile non-haemolytic transfusion reactions).

When looking at the incidence of different types of acute transfusion reactions, we know that less serious transfusion reactions are more common than serious reactions.

- Mild Allergic and Febrile Non-Haemolytic Transfusion Reactions: ~1% of transfusions.

- TRALI: <1 in 10,000 transfusions.

- Anaphylaxis: <1 in 20,000 transfusions.

- Acute Haemolytic Transfusion Reactions: ~1 in 75,000 transfusions.

- Bacterial transfusion-transmitted infection is exceptionally rare in the UK; there was only 1 confirmed case between 2011 and 2020.

When comparing the different blood components, platelets are most likely to cause a transfusion reaction (1:10,000 transfusions). This includes being the leading cause of Allergy and Bacterial Transfusion-Transmitted Infection. Acute Haemolytic Transfusion Reactions are almost always due to Red Blood Cell transfusions.

Initial presentation & management

One of the critical aspects of any acute transfusion reaction is stopping the infusion and urgently assessing the patient.

There is a significant overlap between the signs and symptoms of all the causes of acute transfusion reactions. Signs and symptoms of an acute reaction might include any of the following:

- Airway: Stridor (laryngeal oedema)

- Breathing: Wheeze (bronchospasm), Hypoxia, Tachypnoea

- Circulation: Hypotension, Tachycardia, Hypertension

- Disability: Fever, Chills, Rigor, Pain (bone, muscle, chest, abdominal)

- Exposure: Nausea, Malaise

If a patient is receiving, or has recently received, a blood component and develops any of the above symptoms, you should presume they are undergoing a severe reaction until this has been excluded. Your approach needs to involve assessing them urgently, resuscitating them as necessary, and simultaneously forming a more specific diagnosis.

Your first steps should be as follows:

- STOP THE TRANSFUSION

- Maintain venous access with 0.9% saline

- Complete an ABCDE assessment: includes a full set of observations. Treat abnormalities in ABCDE as you work through each section.

- Re-check patient details against blood details: has the patient been given the right blood?

- Re-check the blood bag itself: is there any discolouration or clotting within the bag?

If a patient is receiving a transfusion and develops one of the above symptoms, your first step should almost always be to stop the transfusion. The only situation when you might continue a transfusion in the presence of life-threatening ABC changes is in cases of massive haemorrhage. In this scenario, the cause of hypotension might be hypovolaemia, rather than a transfusion reaction, and so continuing the blood transfusion may be lifesaving. This will be a decision made by a senior.

Workup

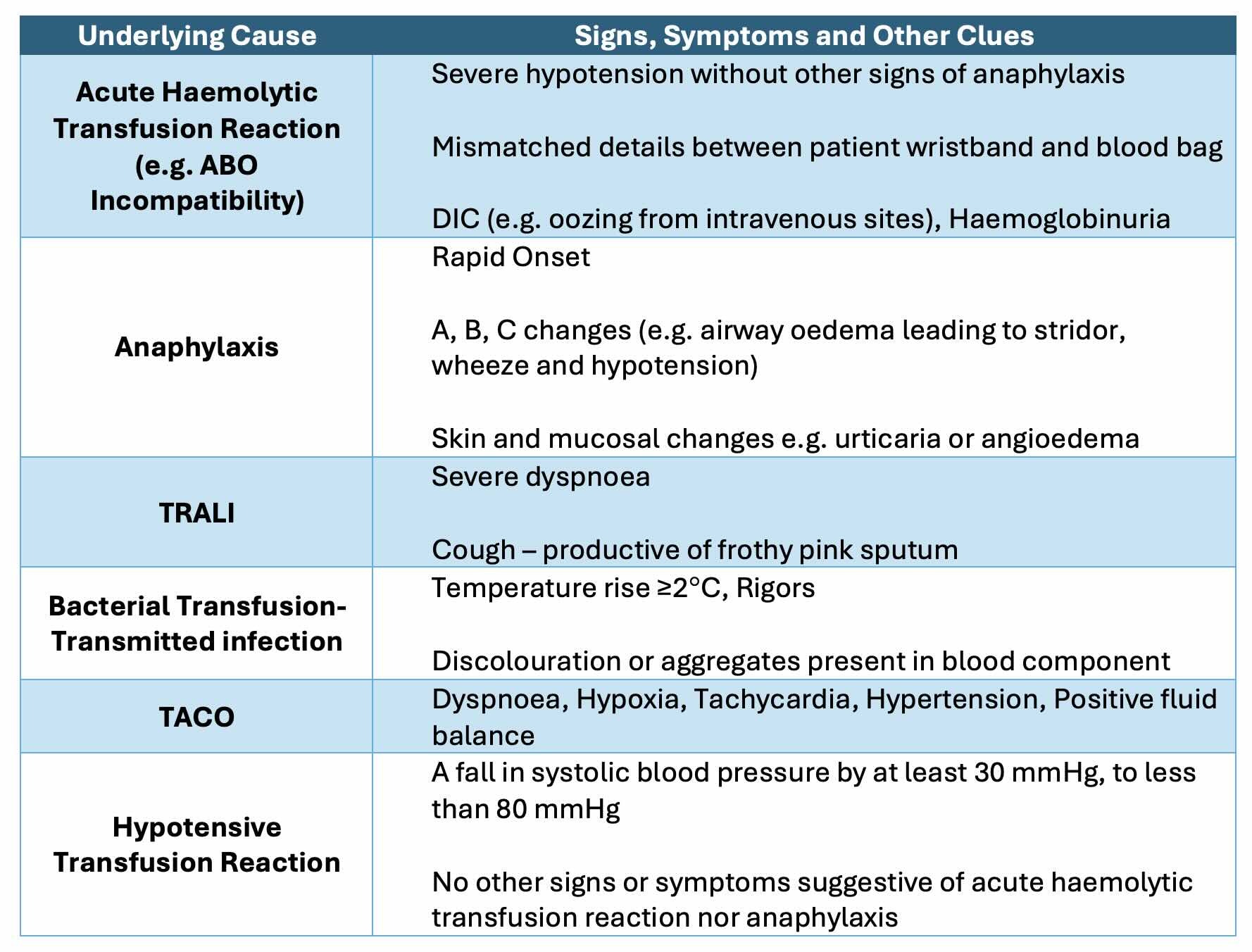

Your clinical assessment can point you toward a specific underlying cause.

In the acute assessment and management of a patient with an acute transfusion reaction, certain signs and symptoms can suggest a specific cause. The table below discusses some of the key clinical features of each acute transfusion reaction.

Management

The ongoing management of an acute transfusion reaction depends on the underlying cause.

After initial assessment, treatment, and resuscitation, ongoing management depends on the underlying cause. Below, we discuss the key aspects of management for each cause of an acute transfusion reaction.

Acute Haemolytic Transfusion Reaction

In an acute haemolytic transfusion reaction, the transfusion must not be restarted. The management is mainly supportive, often with aggressive intravenous fluid. The intensive care team should be involved immediately and the transfusion laboratory should be notified as soon as possible. This is because if the wrong blood has been given to this patient, there is a possibility that there has been a mix-up, and so a second patient might also be at risk of receiving a wrong blood component.

Additional blood tests should be taken and usually guided by the transfusion laboratory, but might include:

- Tests for intravascular haemolysis: serum haptoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), unconjugated bilirubin

- Tests for disseminated intravascular coagulation: clotting screen

- Repeat ABO compatibility tests

Allergic Transfusion Reactions

If the allergic reaction resembles anaphylaxis, do not restart the transfusion, and follow the UK Resuscitation Council's anaphylaxis guidelines. You can find more information on our Note on Anaphylaxis.

If the allergic reaction is mild (i.e. pruritis or urticaria only), the transfusion can be continued after senior review and symptomatic treatment can be given (e.g. antihistamine for pruritis).

TRALI (Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury)

In TRALI, the transfusion should not be restarted and the patient will require supportive treatment with oxygen. In severe cases, the patient may require non-invasive or invasive airway support due to the extent of non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Intensive care should be informed immediately due to the risk of deterioration and the potential need for airway support.

Febrile Non-Haemolytic Transfusion Reactions (FNHTRs)

A febrile non-haemolytic transfusion reaction is usually considered a diagnosis of exclusion once all other acute transfusion reactions have been ruled out. It is vital to ensure there are no ABC changes other than fever +/- chills. If the only signs are fever and/or chills, the transfusion can be continued after senior review and symptomatic treatment (e.g. paracetamol).

Bacterial Transfusion-Transmitted Infection

In a bacterial transfusion-transmitted infection, you must not restart the transfusion. Blood cultures should be taken from the patient and then start broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. The choice of antibiotics will usually by the trust guidance for neutropenic sepsis. The blood bag should be sealed and returned to the transfusion laboratory for further investigation.

Contact the blood transfusion centre so that any associated components, which are likely to also be infected, can be removed from circulation.

TACO (Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload)

In TACO, the patient is likely to be breathless, hypoxic, and by definition, fluid overload. It is important not to restart the transfusion, to provide oxygen therapy according to saturations and to administer diuretics. In severe cases, intensive care support may be needed.

Hypotensive Transfusion Reaction

This is another diagnosis of exclusion. You must ensure there are no ABC changes other than hypotension. In general, the transfusion should not be restarted. A re-trial of transfusion may occur at a later data once the patient has been optimised (e.g. stopping ACE inhibitors if required) after senior review.

Delayed transfusion reactions

You are less likely to encounter delayed transfusion reactions as a junior healthcare professional year doctor.

Here, we will cover the following three types of Delayed Transfusion Reactions:

- Delayed Haemolytic Transfusion Reaction

- Post-Transfusion Purpura

- Transfusion Associated Graft vs. Host Disease

NOTE: We will subsequently discuss the risk of viral infection following transfusion of a blood component.

Delayed haemolytic transfusion reaction

A delayed haemolytic transfusion reaction occurs in patients who have previously generated antibodies to a foreign red blood cell antigen.

To understand delayed haemolytic transfusion reactions, we need to briefly discuss blood groups.

Blood groups

Red blood cells possess a variety of antigens on their surface. Interindividual genetic variation in these antigens gives rise to the blood groups. You will most likely have heard of two of the most clinically important blood groups, the ABO and Rhesus groups. In fact, there are at least 45 blood groups, including antigens in the following blood groups:

- ABO

- Rhesus

- Kell

- Kidd

- Duffy

Pathophysiology

Delayed Haemolytic Transfusion Reactions occur in patients who have previously generated antibodies to a foreign red blood cell antigen. This sensitisation usually occurs after a previous blood transfusion or pregnancy

For example, a patient with Kidd phenotype Jk(A+B-) is transfused a unit of red blood cells with Kidd phenotype Jk(A-B+). The patient will develop antibodies to the foreign JkB antigen present on the surface of transfused red blood cells. If, in the future, the sensitised patient receives another unit of red blood cells which express the JkB antigen, the antibodies they have developed previously will attack the red blood cells, leading to haemolysis

In pregnancy, a pregnant patient who is Rhesus Antigen D negative can carry a fetus which is Rhesus Antigen D positive. If any fetal blood enters the maternal circulation, the mother will generate antibodies to the Rhesus D Antigen. In the future, if the sensitised mother becomes pregnant again with a fetus which is positive for Rhesus D Antigen, then there will be a risk of Rhesus Disease (aka Haemolytic Disease of the Newborn). In the future, if the sensitised mother receives a blood transfusion with Rhesus antigen-positive red blood cells, there is a risk of a transfusion reaction.

It is difficult to identify many of these sensitised patients pre-transfusion. This is because the levels of antibodies present to the various antigens (e.g. Kidd or Rhesus) can fall to undetectable levels after sensitisation. However, on re-exposure to the offending antigen, antibody production is increased, leading to a boost in the patient's antibody levels. These antibodies lead to haemolysis. Unlike in Acute Haemolytic Transfusion Reactions, the haemolysis in Delayed reactions tends to be extravascular.

Presentation

Symptoms are usually mild, and may include:

- Falling haemoglobin levels (or a failure of haemoglobin levels to increase appropriately following transfusion)

- Fever

- Symptoms of haemolysis: jaundice and haemoglobinuria

Management

The management of a delayed haemolytic transfusion reaction is largely supportive. Since the antibodies are likely to fall to undetectable levels again soon after the exposure, they must be identified as soon as possible:

- Liaise with the transfusion laboratory to carry out testing for which antibodies the patient has developed.

- Once you have identified which abnormal antibodies the patient has, this should be recorded on an ‘Antibody Card’ for the patient, and added to a central Blood Services database, to help avoid transfusing blood to which the patient might react in the future.

Overall, patients with a delayed haemolytic transfusion reaction usually do very well.

Post-transfusion purpura

Post-transfusion purpura is rare and characterised by thrombocytopaenia and the development of a purpuric rash.

Post-Transfusion purpura is a rare post-transfusion complication that is often seen in multiparous females and characterised by severe thrombocytopaenia and purpura on the skin around 3-12 days post-transfusion.

Aetiology

The cause of Post-Transfusion Purpura isn’t fully understood.

It is suspected that a patient develops antibodies to a platelet antigen (HPA-1a). Most often this is an HPA-1a negative female patient who has carried an HPA-1a positive fetus in pregnancy. It could also occur if a patient who is HPA-1a negative is transfused platelets from a donor who is HPA-1a positive. If the patient has been sensitised, when/if a red blood cell transfusion is subsequently given it somehow reactivates the patient’s antibodies to the HPA-1a antigen. Even though the patient is HPA-1a negative (i.e. their platelets lack the HPA-1a antigen), somehow the platelets are damaged by the resurgence in HPA-1a antibodies leading to platelet destruction and thrombocytopaenia.

Presentation

The condition is more common in female patients and usually develops 3-12 days after a transfusion. It is characterised by the presence of purpura, which are small, 4-10 mm, patches of extravasated blood from small vessels in the skin. On laboratory testing there is usually profound thrombocytopaenia. It can potentially lead to more life-threatening bleeding episodes.

Management

The treatment is largely supportive, but patients often require treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) which is typically associated with a good response. Over the proceeding weeks, the platelet count will recover.

Transfusion-Associated Graft vs. Host Disease

Transfusion-Associated Graft vs. Host Disease occurs when white blood cells in a blood component ‘engraft’ (i.e. take up residence) in the recipient.

Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease, known as 'TA-GVHD', is a rare complication of blood transfusions. It occurs when lymphocytes in donor blood 'attack' the recipient's tissue.

Aetiology

TA-GVHD occurs when white blood cells in a blood component ‘engraft’ (i.e. take up residence) in the recipient. From here, the transplanted white blood cells will attack the recipient’s own tissue, which they perceive as foreign.

Certain patients are more at risk for white blood cell engraftment. These patients usually have impaired cell-mediated immunity, and so are unable to reject the foreign white blood cells. This included:

- Immunocompromised patients: Primary immunodeficiency, Haematological malignancy, Certain immunosuppressive drugs

- Fetuses receiving intrauterine transfusions

- Neonates receiving transfusions.

The transplanted white blood cells tend to target specific tissues, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), intestinal epithelium, and skin. This helps explain some of the clinical features (see below).

Presentation

The features of TA-GVHD usually develop 7-15 days after a transfusion and include features of:

- Rash

- Fever

- Diarrhoea

- Deranged LFTs

- Bone marrow aplasia and pancytopenia

Management

Treatment options for TA-GVHD are limited, so the key to management is prevention of the condition. Any patient with impaired cell-mediated immunity should receive irradiated blood components. The irradiation inactivates any white blood cells in blood components before they are transfused, meaning they are unable to attach to the recipient’s own tissues.

Unfortunately, once developed TA-GVHD' is usually fatal (75-90% mortality rate).

Viral infection

The risk of transmission of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C via transfusion is now extremely small.

The risk of viral infection used to be higher following blood transfusion. This was because conventional screening tests were based on the detection of viral antibodies in donor blood. This meant a risk of transmission if blood was donated during the window period of a virus (i.e. soon after infection, and before the donor had developed antibodies to the virus). Nowadays blood samples are also tested for viral antigens and for the presence of viral nucleic acids, which can detect the presence of a virus even during the window period.

It is estimated that the risk of transmission is now low.

- Hepatitis B: <1 in 1.2 million donations

- Hepatitis C: <1 in 28 million donations

- HIV: <1 in 7 million donations

Last updated: July 2024

References:

Joint United Kingdom (UK) Blood Transfusion and Tissue Transplantation Services Professional Advisory Committee

British Society for Haematology Guidelines: Guideline on the investigation and management of acute transfusion reactions

Handbook of Transfusion Medicine, 5th Edition, Dr Derek Norfolk, United Kingdom Blood Services

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback