Autoimmune hepatitis

Notes

Overview

Autoimmune hepatitis is a chronic inflammatory liver disorder that can lead to cirrhosis, liver failure and death.

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is one of the major inflammatory disorders of the liver. It classically causes a chronic relapsing hepatitis that, if untreated, can lead to cirrhosis, liver failure and death.

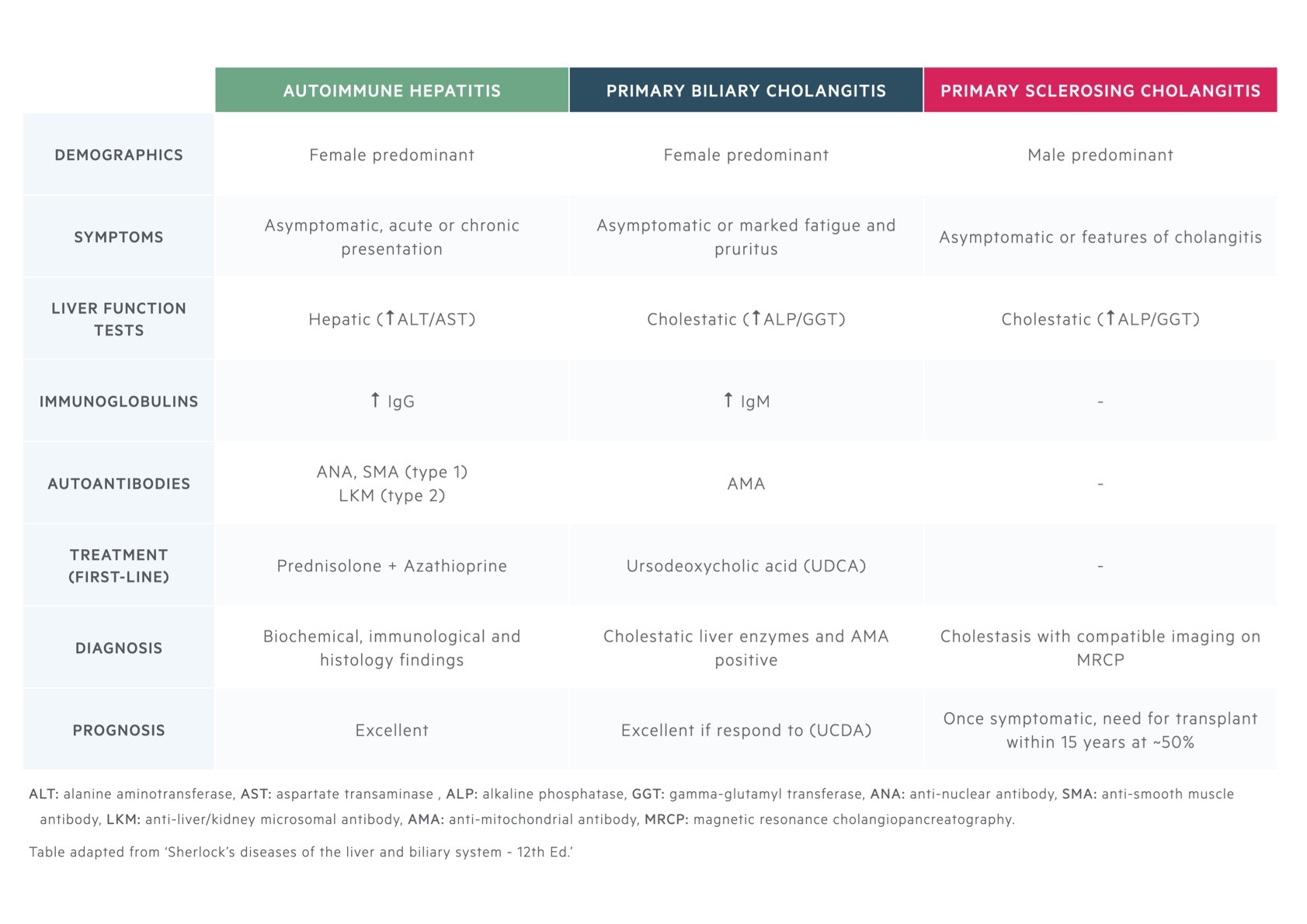

There is a wide spectrum of clinical presentation and the condition may overlap with other liver diseases including primary biliary cholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Epidemiology

AIH may occur at any age and predominantly affects woman.

The prevalence of AIH varies depending on geographical region. In Europe, it ranges from 10-17 per 100,000 population. The disease is seen more commonly in women, but the frequency depends on subtype. There is a 4:1 female predominance in type 1 AIH and 9-10:1 female predominance in type 2 AIH.

Traditionally, AIH was thought to occur predominantly in young woman. However, it may be seen across all ages and ethnicities.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

The exact cause of AIH is unknown.

AIH is characterised by typical immunological features including elevated serum immunoglobulin levels (IgG) and circulating autoantibodies. However, the exact cause of AIH remains unknown.

The disease is thought to develop due to an environmental trigger in a genetically predisposed individual. This leads to the immune system recognising self-antigens (i.e. autoimmunity) with subsequent inflammation and organ damage (i.e. cirrhosis). There are several factors to consider including the immune system, genetics, precipitants and autoantibodies.

Immune system

AIH is thought to develop due to an abnormality in a subset of T lymphocytes known as T regulatory cells (Treg). Treg cells are important for maintaining tolerance to self-antigens and restricting the immune response to target antigens (substance that produces an immune response). If this response is dysfunctional it can lead to autoimmune attack and organ damage.

Genetic determinants

A number of genetic factors have been identified as possible predisposing factors for development of AIH. These are broadly divided into human leucocyte antigen (HLA) and non-HLA loci.

- HLA loci: refer to proteins encoded by the major histocompatibility genes that are involved in cell recognition and antigen processing by the immune system. Divided into class I (A, B, C) and class II (DP, DQ, DR). Specific genotypes (i.e. alleles) of the serotypes HLA-DR3 and DR4 have been implicated in AIH.

- Non-HLA loci: regions associated with the immunoglobulin heavy chains and T cell receptor have been implicated in AIH.

Other genes involved in immunoregulation have been implicated in development of autoimmune diseases such as AIH. These include T cell receptor CTLA-4 and the transcription factor autoimmune regulatory type 1 (AIRE-1). AIRE-1 regulates clonal deletion of autoreactive T cells (i.e. cells that attack self-antigens) that is implicated in autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1 (APS1)

Precipitants

The majority of AIH cases have no readily identifiable precipitant. Precipitants may include herbal chemicals, drugs or viral infections. Several viruses have been implicated in triggering AIH including hepatitis A and human herpes viruses (e.g. herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr).

Drugs and herbal chemicals are major causes of liver injury, including both hepatocellular and cholestatic liver injury. Several drugs may precipitate an autoimmune-like hepatitis including minocycline, nitrofurantoin, methyldopa, halothane, Anti-TNF biologics and many others. Administration of interferon therapy may induce or unmask autoimmune hepatitis.

Histological changes

Liver biopsy forms a core component of the diagnosis of AIH. It enables exclusion of alternative pathologies and to assess the degree of fibrosis. There are common histological features in keeping with AIH, which include:

- Interface hepatitis: inflammation and fibrosis at the lobular-portal interface (between lobules of hepatocytes & portal tracts).

- Lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates: infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells into the portal tracts and extending to the lobules.

- Hepatocyte necrosis: death of hepatocytes, usually in periportal areas. Necrosis extending between terminal venules and portal tracts may be seen, which is termed ‘bridging necrosis’.

- Hepatic Rosette formation: gland-like formations (Pseudoacini) that develop due to chronic inflammation.

Autoantibodies

Certain circulating autoantibodies are characteristic of AIH.

Autoantibodies refer to antibodies that target self-antigens. They can be found in many autoimmune diseases with different disease specificity, including AIH.

Autoantibodies seen in AIH:

- Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA): antibodies targeted against nuclear proteins and/or DNA. Non-specific, seen in other autoimmune diseases.

- Anti-smooth muscle antibody (SMA): antibodies targeted against actin, tubulin and other proteins.

- Anti-liver/kidney microsomal antibody (LKM): antibodies targeted against mitochondrial enzymes.

- Anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA): strongly associated with primary biliary cholangitis. Seen in 20% of AIH.

- Anti-soluble liver and pancreas antigen (SLA/LP): antibodies that target a tRNA-associated protein. Seen in 75% of type 1 AIH.

While circulating autoantibodies form the hallmark of AIH, there is little evidence to support their role in the pathogenesis.

Disease classification

Autoimmune hepatitis is classically divided into type 1 and type 2 AIH.

There are different disease subtypes of AIH, which have differences in clinical and serological features. These are usually classified according to autoantibody profiles.

Disease subtypes

- AIH type 1

- AIH type 2

- Seronegative AIH

AIH type 1

This is the predominant form of AIH. It is characterised by ANA and SMA antibodies. The peak incidence is between 16-30 years, and affects women in >70% of cases. Acute presentations are rare, approximately 25% have cirrhosis at diagnosis and there is an overall better response to treatment.

AIH type 2

This form is more commonly seen in children with an average age of presentation of 10 years. Similar to AIH type 1, there is a female predominance, but it is associated with LKM antibodies. Overall, this form has a more aggressive picture with 80% developing cirrhosis and it is more likely to be treatment resistant.

Seronegative

Up to 20% of patients with typical features of AIH will be autoantibody negative.

NOTE: a third type of AIH is occasionally described in association with anti-SLA/LP antibodies. This is because these antibodies were originally identified in seronegative patients. However, 75% of these patients are also ANA and SMA positive.

Clinical features

Patients with AIH may be asymptomatic and the diagnosis picked up incidentally on blood tests.

There is a wide spectrum of presentation in AIH

- Asymptomatic

- Acute hepatitis

- Chronic liver disease (cirrhosis)

- Acute liver failure

Asymptomatic

Patients may be diagnosed incidentally on abnormal liver imaging or persistently abnormal blood tests. An estimated 25% of patients with AIH are asymptomatic at diagnosis.

Acute hepatitis

An acute hepatitis can occur in up to 40% of patients. Type 2 AIH is more likely to present acutely.

- Anorexia

- Nausea

- Coryzal symptoms

- Jaundice

- Right upper quadrant pain

- Hepatomegaly

Chronic liver disease

Approximately 30% of patients will have cirrhosis at presentation, which suggests clinically silent hepatitis prior to diagnosis. Clinical features may be non-specific and be present for months or years.

- Non-specific features: anorexia, nausea, weight loss, amenorrhoea, arthralgia or arthritis, acne, unexplained fever

- Stigmata of chronic liver disease: hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, palmar erythema, spider naevi

- Complications of cirrhosis (i.e. decompensation): ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice, GI bleeding

For more information see Chronic liver disease notes

Acute liver failure

AIH rarely presents with acute liver failure. This is characterised by jaundice, confusion and coagulopathy in the absence of underlying liver disease. Patients are very sick and need urgent transfer to a transplant centre.

Association with other autoimmune disease

In an estimated 30-50% of patients, AIH is associated with another autoimmune disease. The most commonly implicated causes include:

- Primary biliary cirrhosis

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Coeliac disease

- Thyroiditis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Other connective tissue diseases

Diagnosis

There are no specific clinical or biochemical markers to enable a simple diagnosis of AIH.

Unfortunately, there is no single diagnostic test that enables a confident diagnosis of AIH. This has led to the use of scoring systems to aid the diagnosis. Despite these tools, diagnosis can still be difficult in atypical cases. This may warrant a trial of treatment.

Scoring systems

In the early 1990s, the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) developed a scoring system designed as a research tool to aid the diagnosis of AIH. This took into account clinical, biochemical, immunological and histological data to come to a definite or probable diagnosis.

Components of the score include:

- Gender

- Liver enzymes

- Serum globulins and/or IgG levels

- Autoantibodies

- Hepatitis viral markers

- Alcohol intake

- Liver histology

- Genetic factors or other autoimmune disease

- Response to treatment

This scoring system was later revised and can be used in clinical practice. Variables are given a weighted score with a definite diagnosis given to a total score > 15 and probable diagnosis to a total score between 10-15. A simplified version of this score has since been developed. A post treatment score can also be calculated in patients given a trial of steroids.

Investigations

Investigations are crucial to confirm the diagnosis, assess for other causes and determine the degree of liver disease.

A full clinical assessment, basic biochemical tests, non-invasive liver screen and imaging are needed as part of assessment. A liver biopsy if often completed as part of the assessment to help confirm the diagnosis.

Routine bloods

In acute hepatitis, transaminases (ALT/AST) are often in the thousands. In chronic disease, they may be mildly elevated.

- Full blood count

- Urea & electrolytes

- Liver function tests

- Clotting profile

Non-invasive liver screen

A non-invasive liver screen refers to screening questions, biochemical tests and imaging to assess patients with suspected liver disease. As part of a non-invasive liver screen, autoantibodies are checked including ANA, SMA, LKM and immunoglobulins.

AIH is characterised by positive autoantibodies and elevated levels of immunoglobulin IgG. This is reflected in the diagnostic criteria. Autoantibodies are useful to help categorise the disease (e.g. Type 1, Type 2, seronegative).

Imaging

Liver imaging is not used to make the diagnosis of AIH. There are no specific features that separate it from other pathologies. Instead, it is needed to assess for cirrhosis and features of portal hypertension, exclude differentials (e.g. US with dopplers for Budd-Chiari syndrome) and look for overlap syndromes (e.g. MRCP for cholangiopathy).

Liver ultrasound (US) with dopplers, CT or MRI can be used to assess the liver. US with dopplers is a good screening test and can assess vessel patency (hepatic and portal veins). More detailed imaging of the liver with MRI or MRCP may be needed to exclude a cholangiopathy (disease of bile ducts).

Liver biopsy

Liver biopsy is commonly undertaken to aid the diagnosis of AIH. Histological features form part of the diagnostic criteria and it enables assessment of liver injury (e.g. bridging necrosis, cirrhosis) and exclusion of other pathologies.

Can be completed by percutaneous approach with US guidance or transjugular approach.

Overlap syndromes

The presence AIH with another autoimmune liver disease (PBC or PSC) is known as an ‘overlap syndrome’.

Overlap syndromes are a challenging area. They are defined as the concurrent presence of two autoimmune conditions at the same time or during the course of the illness. AIH may overlap with PBC or PSC.

The defining characteristics of all three of these autoimmune liver diseases are summarised.

AIH/PBC overlap

Approximately 5-10% of patients with PBC will overlap with AIH. Criteria are often used to define an overlap because isolated features of PBC are commonly found in AIH and vice versa (e.g. AMA positive or bile duct lesions).

AIH/PSC overlap

Based on MRI findings, up to 12% of adults with AIH have evidence of PSC. There are no specific criteria and diagnosis is based on classic imaging and histological changes.

Management

The mainstay of treatment for AIH is immunosuppression with steroids and azathioprine.

The goal of treatment in AIH is to suppress the immune system from damaging the liver with the use of immunosuppressive agents. In doing so, this helps to prevent both progression to cirrhosis and development of adverse features.

Indications

The majority of patients are treated for AIH. This is pertinent for patients with moderate-to-severe inflammation (e.g. AST or ALT >5x ULN, serum globulins >2x ULN or confluent necrosis on liver biopsy), those with established cirrhosis or younger patients with the aim to reduce the risk of developing cirrhosis. It may be more appropriate to monitor some patients groups (older patients with minimal inflammation).

Pharmacotherapy

The principle treatment of AIH is use of steroids (e.g. prednisolone) and azathioprine.

Prednisolone is typically started at 30 mg/day (reduced to 10 mg/day over four weeks) and this is followed by azathioprine after several weeks. A rapid improvement in liver function tests may give reassurance as to the diagnosis. Alternatively azathioprine can be started at the time of steroid initiation. The dose of azathioprine is usually 1 mg/kg/day.

Azathioprine is a purine synthesis inhibitor and used in a variety of inflammatory and/or autoimmune conditions (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease). It prevents formation of DNA and RNA following metabolism by the liver into its active metabolite 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP). The enzyme TPMT is important to inactivate 6-MP into less toxic molecules. Some patients have low levels of TPMT, which leads to accumulation of 6-MP and conversion to more toxic metabolites. This can lead to bone marrow suppression. Therefore, TPMT levels need to be checked prior to initiation of therapy.

Follow-up

The aim of treatment is to achieve clinical remission with complete resolution of liver transaminases (ALT/AST). This may require dose escalation of prednisolone and/or azathioprine to achieve.

Generally, treatment should continue for two years, or at least 12 months following normalisation of liver transaminases. Repeat biopsy to assess for histological remission may be needed to determine whether long-term therapy is needed. A significant proportion of patients will relapse following withdrawal of therapy so long-term therapy with azathioprine +/- prednisolone is often needed with close follow-up. Different factors may influence whether continuation or trialling withdrawal is appropriate.

All patients will be on long-term steroids, at least initially, so calcium supplementation, DEXA imaging (to investigate for osteoporosis) and need for prophylactic bisphosphonates should be considered.

Additional therapies

Other immunosuppressive agents may be considered in AIH with specialist input:

- Ciclosporin: calcineurin inhibitor

- Tacrolimus: calcineurin inhibitor

- Mycophenolic mofetil: purine synthesis inhibitor

- Budesonide: an alternative to prednisolone with reduced systemic side-effects due to 90% first-pass hepatic metabolism

An estimated 10-20% of patients with AIH will require liver transplantation during their lifetime. The same indications for liver transplantation are used for AIH as in other causes of cirrhosis. Patients needing transplantation should be referred for assessment at a transplant centre.

Prognosis

Around 30% of patients have cirrhosis at the time of diagnosis and a further 30-50% develop it during follow-up.

AIH is a chronic relapsing disease with a high likelihood of developing cirrhosis. Patients who are treated have a good ten-year survival around 90%. Without treatment, mortality rates are much higher particularly in symptomatic patients.

Unfortunately, despite treatment 50-90% will relapse within 12 months of stopping therapy and many require life-long immunosuppression. The needs for liver transplantation is estimated at 10-20% during a patients lifetime with a good five-year survival. Among those transplanted, there is a 20-30% risk of recurrence of AIH in the graft.

In patients with cirrhosis, surveillance for HCC is recommended because the risk of developing HCC is 10-20% over 20 years.

Last updated: July 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback