Neutropenic sepsis

Notes

Definition

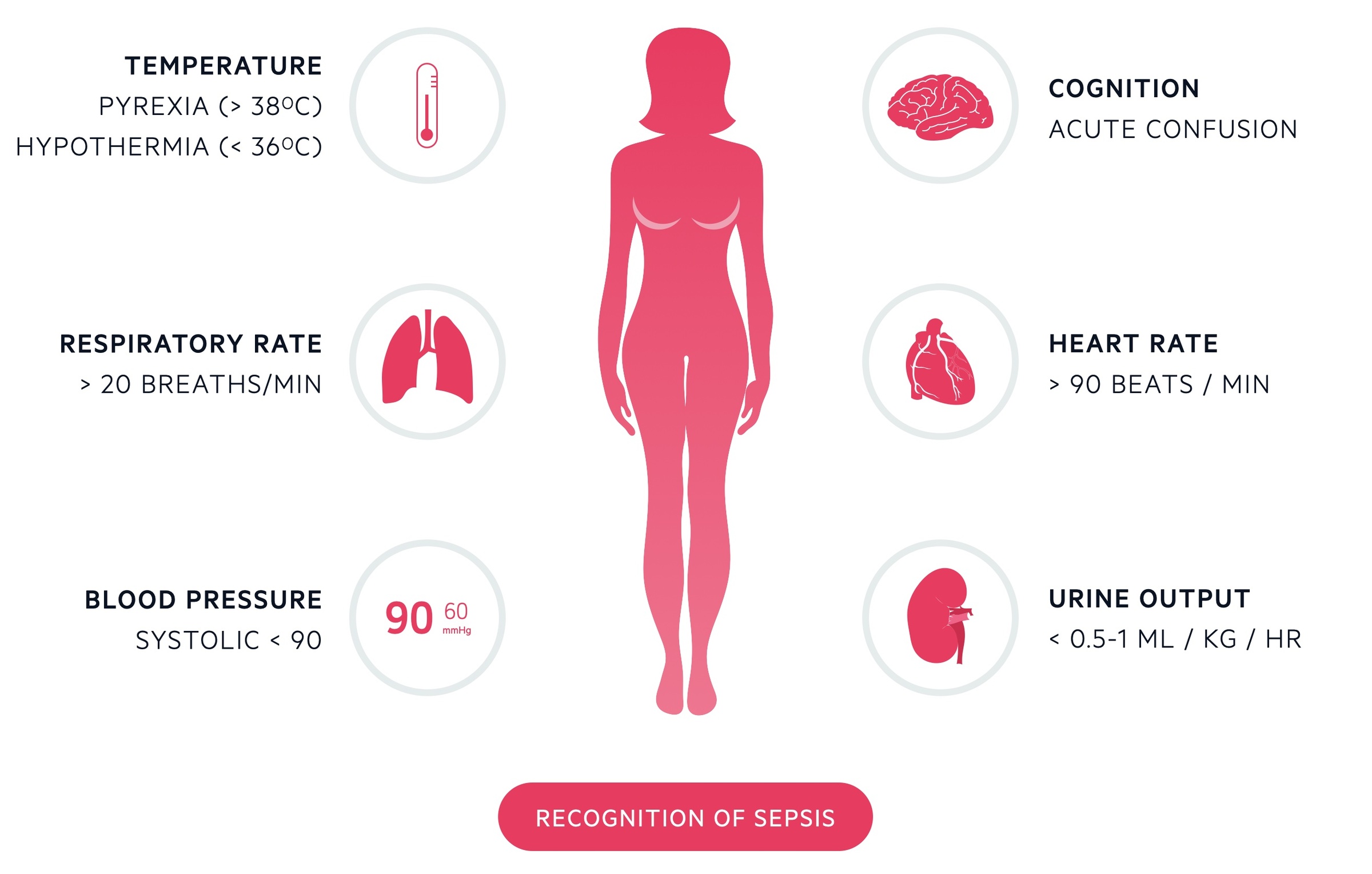

Neutropenic sepsis may be defined as fever > 38° or features of sepsis* in a patient with a neutrophil count of < 0.5 x 109/L (or expected to fall to below 0.5).

Neutropenia refers to a fall in the level of circulating neutrophils. The severity of neutropenia is dependent on the ‘absolute neutrophil count’ (ANC). A normal neutrophil count ranges from 2.5-7 x109/L.

Neutropenia is generally defined as an ANC < 1.5 x109/L with severe neutropenia said to be an ANC < 0.5 x109/L. At an ANC < 1.0 x109/L patients are considered immunocompromised, with an increased risk of life-threatening infections.

Neutropenic sepsis should be treated as a medical emergency with investigations and antibiotic therapy within the first hour following detection.

*NOTE: The absence of effective immune cells impairs the bodies ability to mount a proper immune response and as such normal clinical features of infection may be subtle or absent.

Aetiology and pathophysiology

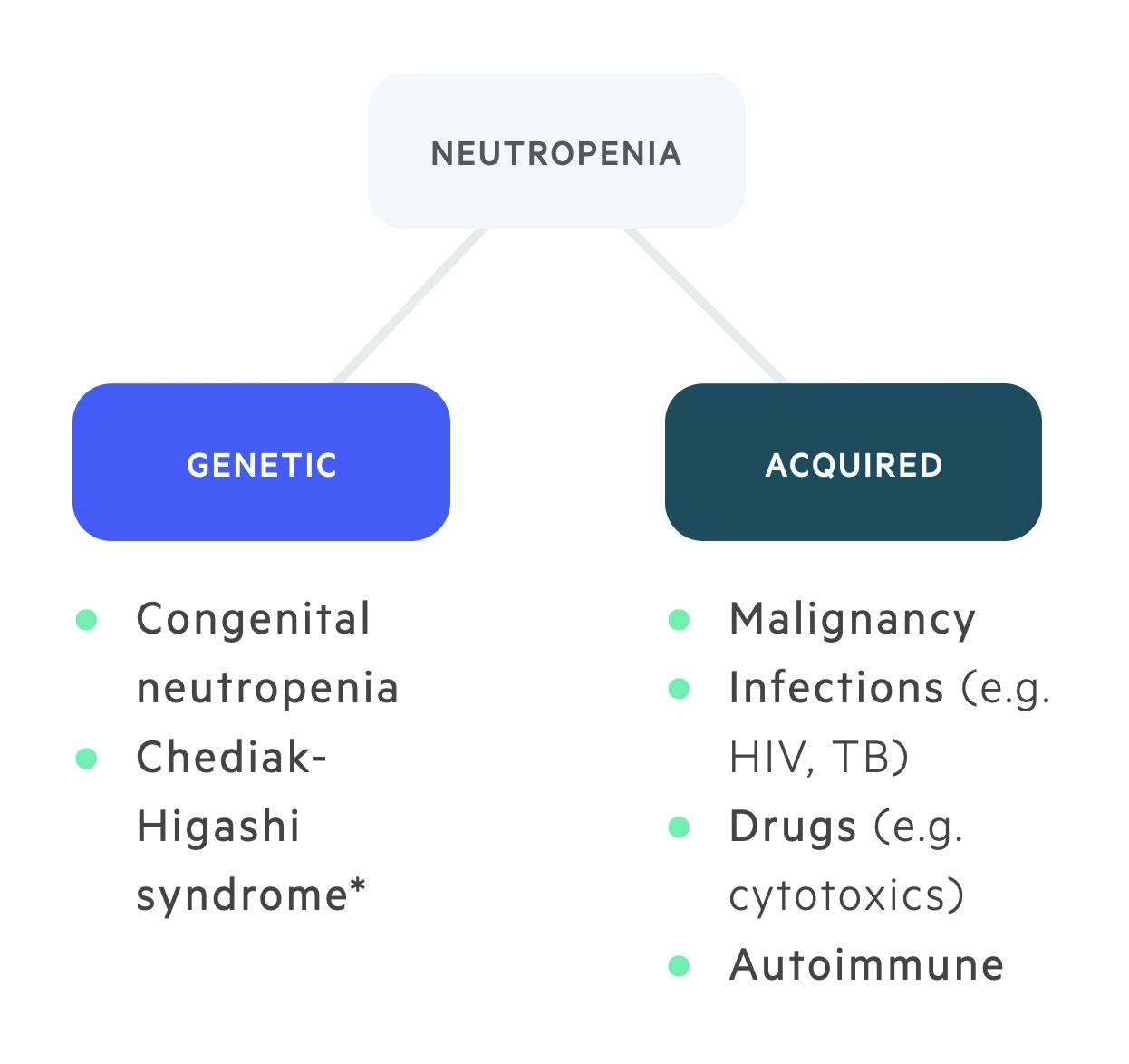

Causes of neutropenia may be categorised as congenital or acquired.

Genetic

Congenital causes of neutropenia are rare and usually associated with mutations in genes that are critical for the normal maturation and functioning of neutrophils.

Examples of inherited neutropenic syndromes include severe congenital neutropenia and Chediak-Higashi syndrome.

Cytotoxic related

Cytotoxic therapy targets rapidly dividing cells such as those within the bone marrow. This leads to a reduction in the production of neutrophils.

Intrinsic disease of the bone marrow

A number of disease processes may affect the bone marrow. These include malignant causes (haematological malignancies and tumour infiltration), aplastic anaemia and ionising radiation.

Infections

A wide-range of infections can result in neutropenia. Examples include bacterial sepsis, viral infections (e.g. human herpes virus 4 & 5), malaria and typhoid.

Immune-mediated

Autoimmune neutropenia is uncommon. It is frequently associated with inflammatory conditions (e.g Crohns) and arthritides (e.g rheumatoid arthritis).

Drugs may also lead to neutropenia through immune-mediated mechanisms. In these cases, drugs stimulate the formation of antibodies that directly damage granulocytes. This may be seen with anti-thyroid drugs (carbimazole, propylthiouracil).

Nutritional deficiencies

Deficiencies in folate and vitamin B12 may lead to ineffective neutrophil production.

Increased neutrophil turnover

In these conditions, neutrophils are destroyed at such a rate the bone marrow is unable to adequately replace them. This occurs in bacterial infections and hypersplenism.

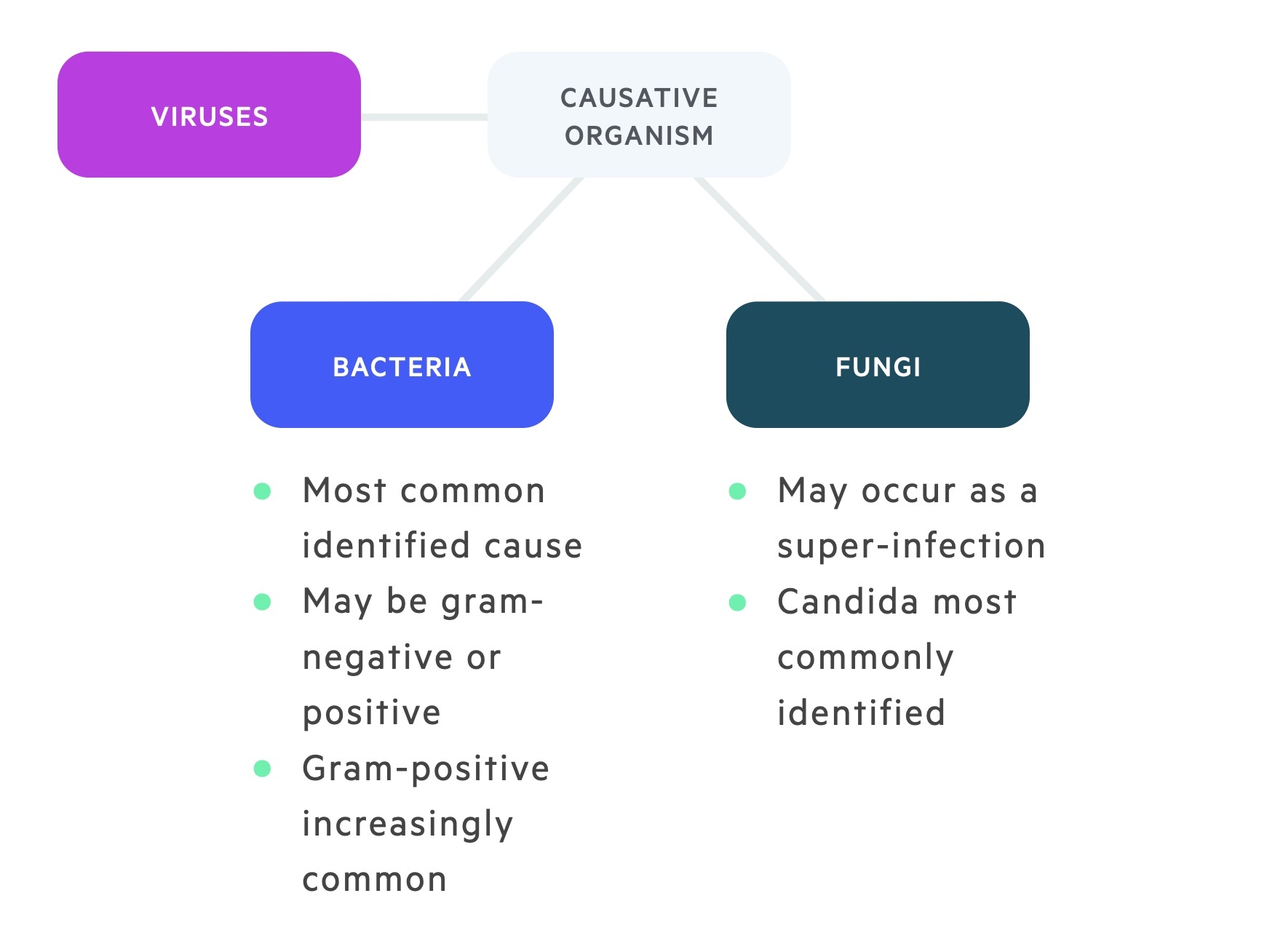

Causative organisms

Bacteria are the most commonly isolated organisms in neutropenic sepsis.

Other causes include viruses and fungi. Importantly, an infective organism is only found in 20-30% of cases.

Bacteria

In the 1960s and 1970s the bacteria isolated were predominantly gram-negative. With the rising use of indwelling catheters in the decades that followed the incidence of gram-positive bacteria increased. Coagulase-negative staphylococci and pseudomonas aeruginosa septicaemias are now common. Enterobacteriaceae (e.g. E.coli, Klebsiella) remain important causes.

Examples of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria leading to neutropenic sepsis are detailed below:

- Gram-negative

- Escherichia coli

- Klebsiella spp

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Gram-positive bacteria

- Coagulase-negative staphylococci (e.g. S. epidermidis)

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Other

- Clostridium difficile

Viruses

Viral causes of neutropenic sepsis may be seen in high-risk patients and are usually prevented with the use of prophylactic antiviral therapy. Offending organisms are usually part of the human herpes virus family including herpes simplex viruses (HHV 1 and 2), varicella zoster virus (HHV 3), Epstein-Barr virus (HHV 4), cytomegalovirus (HHV 5), and HHV 6 in bone marrow transplant patients.

These human herpes viral infections are usually secondary to reactivation of latent infections and can cause a wide variety of syndromes if not anticipated with prophylactic antivirals.

Other viral infections may include respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus, and parainfluenza virus.

Fungi

Like viral infections, fungal infections are more common in high-risk patients. The overall risk of fungal infections increases with the length and severity of neutropenia and the number of cycles of chemotherapy.

Typical fungal pathogens include Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp. Candida is a normal commensal of the gastrointestinal flora and may translocate across damaged epithelium. Aspergillus may enter the respiratory tract via inhaled spores.

The use of prophylactic anti-fungal therapy is dependent on risk stratification of the patient and the underlying diagnosis. Patients with haematological malignancies often require anti-fungal prophylaxis (e.g. fluconazole).

Clinical features

An impaired immune system may have a blunted response with subtle signs, a high index of suspicion may be needed.

Patients may present with the signs and symptoms of a specific infection. For example a purulent cough indicating pneumonia or dysuria indicating a UTI may be described. Often however patients simply present with a fever or (often non-specific) signs of systemic infection such as malaise and fatigue.

Neutropenic sepsis should be considered in any patient at risk of neutropenia presenting with the clinical features of infection. Most frequently this will be encountered in a patient receiving or having recently received chemotherapy.

Investigations

Investigations are aimed at identifying the source of infection and evidence of organ dysfunction or complications.

Bedside

- Observations

- Blood sugar

- Pregnancy test

Bloods

- VBG / ABG

- FBC

- CRP

- U&Es

- LFTs

- Bone profile

- Clotting

- Fungal assays (e.g. beta-d-glucan galactomannan)

- Blood borne virus screen

Cultures

- Blood cultures

- Line cultures

- Sputum MC&S

- Urine cultures

- Stool MC&S

- C. diff toxin

- Viral PCR

- Wound swabs

Imaging

- Chest X-ray

- Lumbar puncture (meningitis, encephalitis)

- ECHO (infective endocarditis)

Sepsis six

All patients with suspected neutropenic sepsis should be managed with the sepsis six care bundle.

The sepsis six bundle is a protocol by which a patient may be investigated and treated for sepsis. It is by no means exhaustive but incorporates key investigation and treatment points. The bundle should be initiated and completed within one hour of recognition of the signs.

Patients with haemodynamic instability, a lactate greater than 2 or evidence of end-organ dysfunction should receive urgent review by a senior clinician and a MET/Peri-arrest call if indicated.

Three In

Patients should receive high flow oxygen to achieve appropriate target saturations. A target of 94-98% is appropriate for the majority of patients. Those at risk of carbon dioxide retention (COPD) should have a target of 88-92%. IV fluids should be started, often 500ml of crystalloid over 15 minutes with reference the patient's haemodynamic status and co-morbidities. Antibiotics are key and should be given without delay, NICE recommend empirical treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam (tazocin).

Three out

A minimum of two sets of blood cultures should be taken. Ideally, this should happen prior to administration of antibiotics though they should not be a cause for delay. A serum lactate should be obtained normally via a blood gas (arterial or venous) to help assess the patient's status. Urine output should be measured ideally with a catheter with a careful fluid balance recorded.

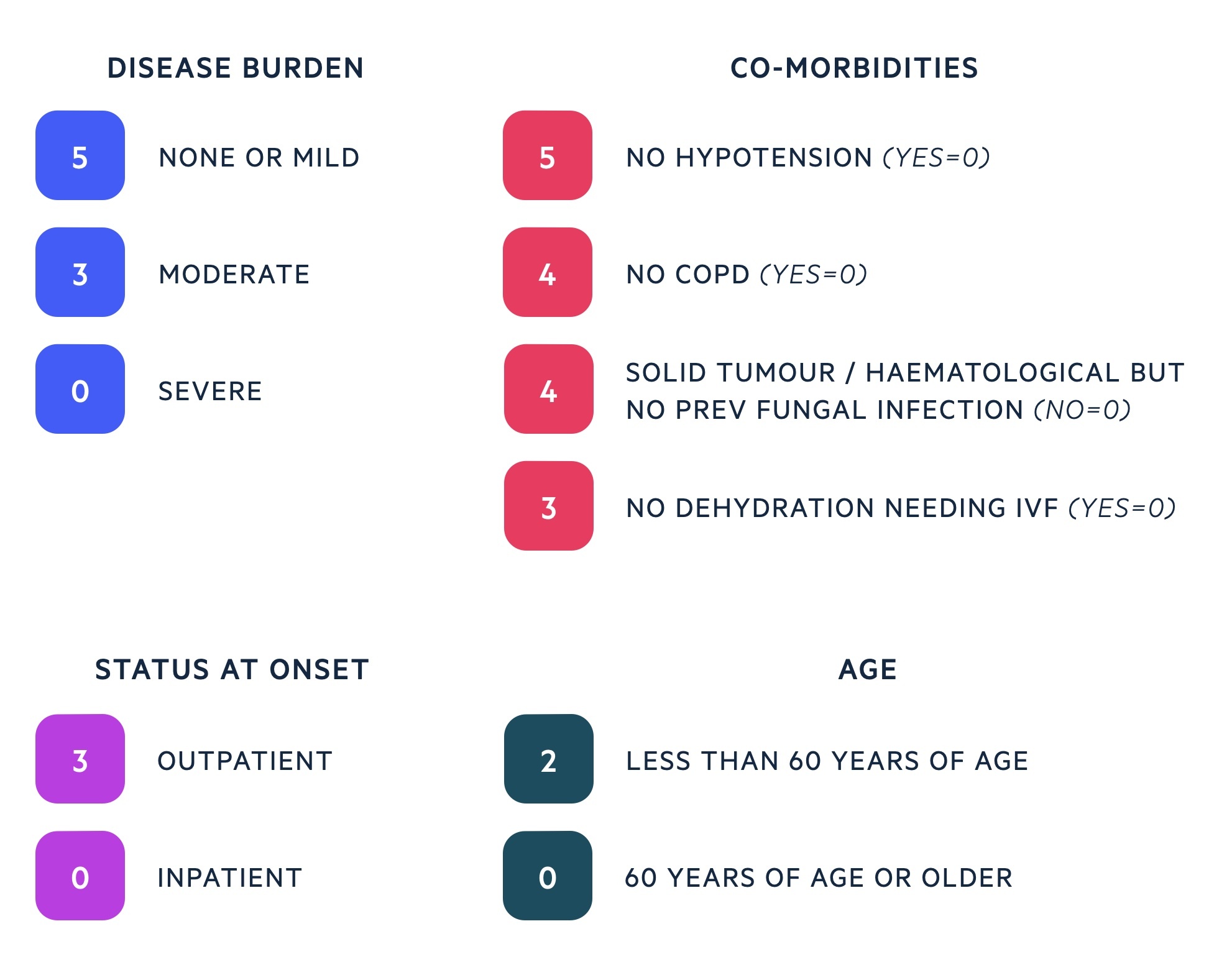

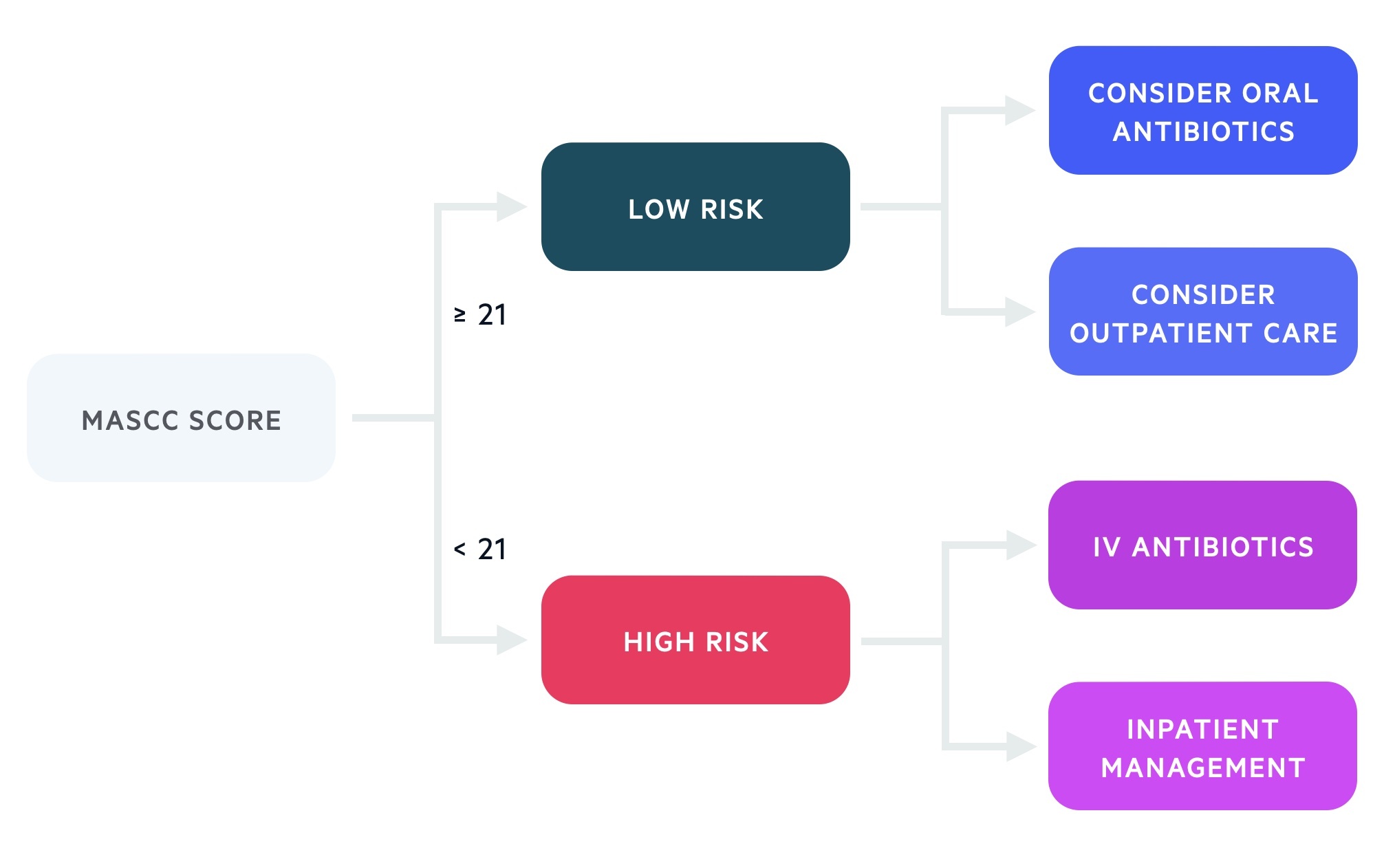

MASCC Risk Index

Patients with neutropenic sepsis can be risk stratified with the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) Risk Index which guides further management.

It takes into account a patients disease burden, co-morbidities, status at onset of fever and age. A high score reflects a patient at lower risk of severe infection that may be suitable for outpatient care.

The MASCC Risk Index helps to guide ongoing management once the sepsis six bundle is complete. Haematology, oncology and microbiology opinion should be sought and used in addition to the MASCC Risk Index to determine the best antibiotic therapy and place of care.

- Low risk (≥ 21)

- High risk (< 21)

High-risk patients have a higher morbidity and mortality. Early identification will help govern admission, therapy choices, level of care and specialist input. These patients are more likely to develop invasive viral and fungal infections requiring prophylactic or empirical treatment.

Management

Patients with neutropenic sepsis require antibiotics and an attempt to identify the source of infection.

The sepsis 6 bundle should be completed in all patients. Additional efforts should be made to identify the source of infection, particularly if not clinically apparent. CXR and urine culture are routine, further imaging may be ordered (e.g. CT C/A/P, CT head) as guided by symptoms and if occult infection is suspected.

The MASCC score can be used to help guide management. However input from haematology/oncology, microbiology and their regular team is essential. Patients who are very unwell may need admission to HDU/ITU for ionotropic support.

Low-risk

Low-risk patients may be managed with oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis (with follow-up and advice to return if state deteriorates). Some cases will still be managed with intravenous antibiotics as an inpatient at least for the first 24-48 hours.

High-risk

High-risk patients should be admitted and (after their sepsis six bundle is initiated) continued on empirical intravenous therapy (typically tazocin). If there are historical microbiology results these should be discussed with microbiology and coverage amended accordingly. Those with indwelling venous catheters are typically covered for MRSA (e.g. with Vancomycin) until culture results have returned.

Changes should only be made to antibiotics if there is a clinical deterioration or guided by culture results. At 48 hours antibiotic therapy should be rediscussed with microbiology.

Last updated: November 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback