Urinary tract infections

Notes

Definition & classification

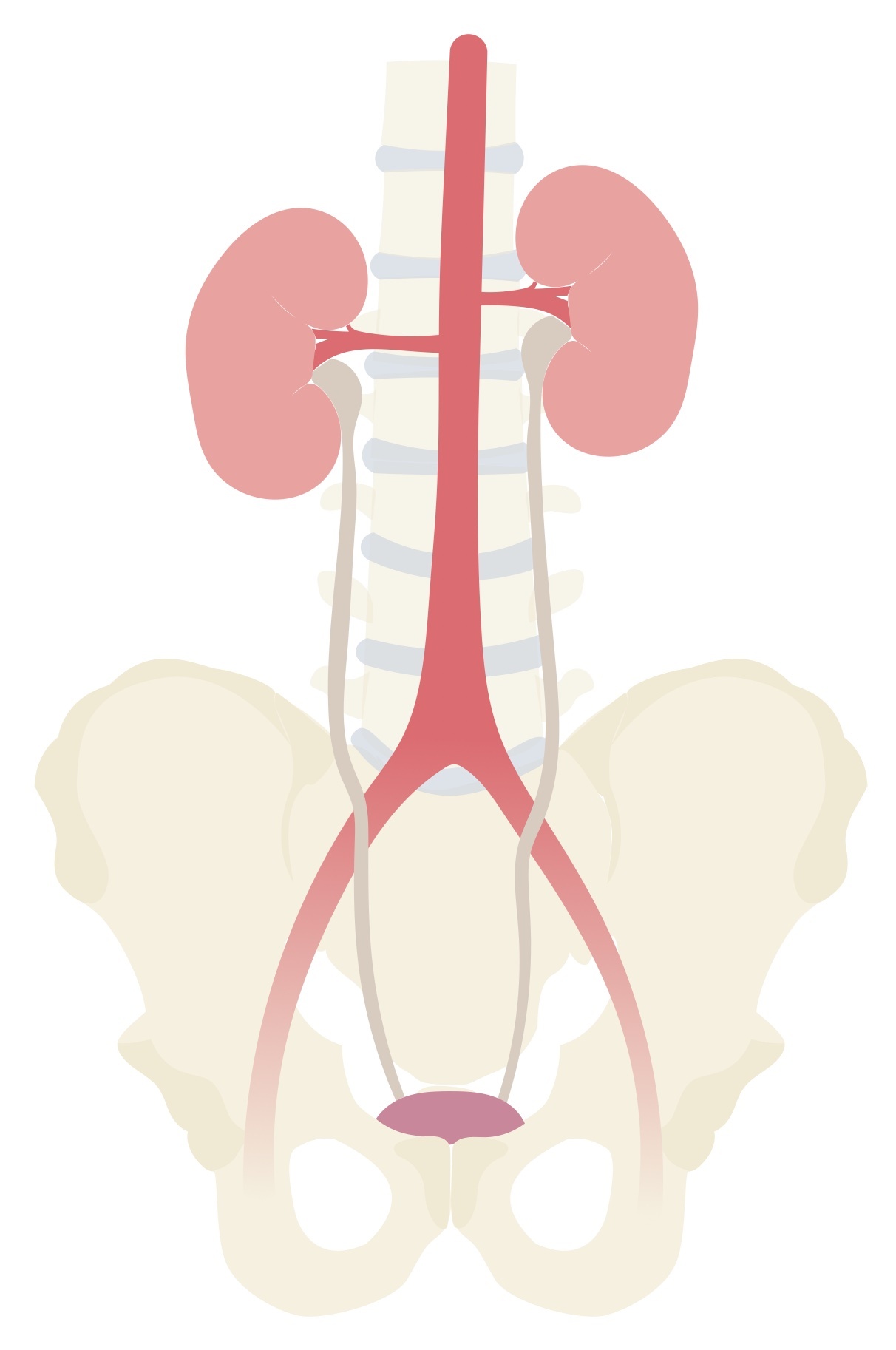

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) refer to an infection of any part of the urinary system from kidney to the urethra.

UTIs are generally defined as the presence of characteristic symptoms (e.g. dysuria, frequency) and significant bacteriuria (presence of bacteria in urine). Significant bacteriuria is defined as > 105 colony forming units (CFU)/ml. In the absence of symptoms, this level of bacteriuria is termed asymptomatic bacteriuria.

UTIs can be further categorised depending on the location of infection (e.g. upper or lower) or the presence of co-morbidities (e.g. complicated or uncomplicated).

Upper UTI: infection of the kidney (pyelonephritis)

Lower UTI: infection of the bladder (cystitis) and urethra (urethritis)

Uncomplicated UTI: if occurring in healthy non-pregnant adult women

Complicated UTI: the presence of factors that increase the risk of treatment failure (e.g diabetes, structural abnormalities, catheter and other devices and all UTIs in men)

UTIs occurring in men are generally considered ‘complicated’ as many occur in children and the elderly in association with urological abnormalities, malignancy or immunosuppression.

NOTE: Please see our separate note for acute bacterial prostatitis.

Aetiology

UTIs are caused by the organism Escherichia coli in 75-90% of cases.

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a gram-negative bacillus that is a facultative inhabitant of the large intestines. E. coli may cause a wide range of infections including, respiratory infections, intra-abdominal infections, enteric infections and urinary infections.

Uropathogenic strains of E. coli infect the urinary tract leading to a wide range of problems including urethritis, prostatitis, cystitis, pyelonephritis and urosepsis.

Other common microorganisms associated with UTIs include:

- Proteus mirabilis

- Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Staphylococcus saprophyticus

ESBL

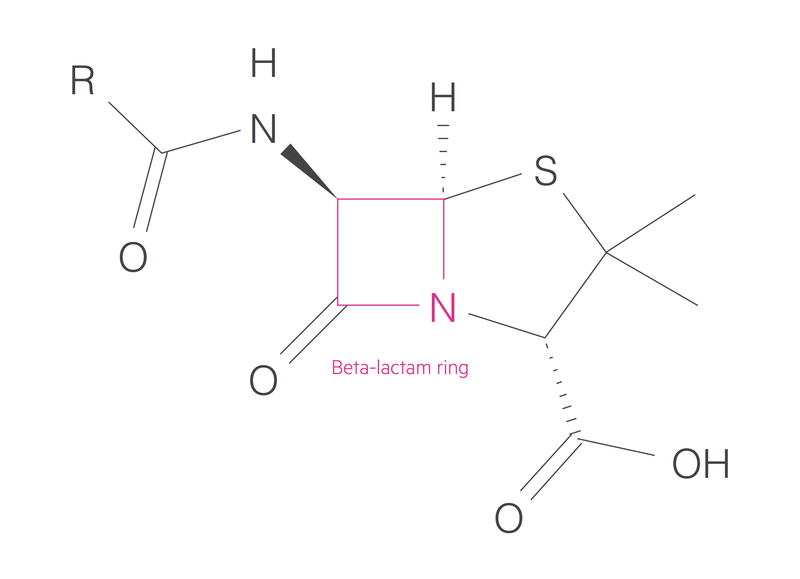

A growing number of UTIs are secondary to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing E. coli.

These organisms are highly resistant to most beta-lactam antibiotics, which includes penicillins and cephalosporins. Beta-lactamases are enzymes which open the beta-lactam ring of beta-lactam antibiotics rendering them inactive.

ESBL infections are a growing cause of hospital-acquired infections associated with poor outcomes. The risk of developing ESBL infections is linked to the prior administration of antibiotics, the length of ITU stay and the presence of a urinary catheter, among others. Treatment often requires potent, broad-spectrum antibiotics (e.g. Carbapenems).

Pathophysiology

The normal urinary tract is a sterile environment.

The development of UTIs results from colonisation and ascending spread of microorganisms from the urethra into the bladder (lower) and kidney (upper), or by haematogenous spread via the blood. Many pathogens have adaptions that allow them to breach host defences.

Microorganism spread

In women, infections start with the colonisation of the vaginal introitus (entrance to the vaginal canal) and periurethral area. It then ascends the urethra to cause infection of the bladder. Infections are uncommon in men for a number of reasons. They have a longer urethra, prostatic secretions have some antimicrobial properties and their periurethral area is generally drier.

UTIs may also develop from the haematogenous spread of microorganisms. However, common gram-negative bacilli (e.g. E. coli) are unlikely to cause infection by this route. Haematogenous spread is more often seen with uncommon urinary microorganisms such as Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Host and pathogen

The ability of microorganisms to infect the urinary system is dependent on both the host and pathogen. Host factors such as intercurrent illness, immunosuppression (e.g. steroid use) or co-morbidities (e.g. diabetes) can increase the risk of developing a UTI.

Some pathogens are particularly well suited to infecting the urinary tract. For example, uropathogenic strains of E. coli contain fimbriae, these are hair-like protein polymers that project from the bacterial surface. They allow strong adherence to the urothelium. Fimbriae play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of UTIs and have been shown to increase bacterial survival.

Risk factors

UTIs are extremely common especially among young, sexually active females.

Risk factors for the development of UTIs include:

- Recent sexual intercourse

- Diabetes

- History of UTIs

- Spermicide use

- Catheters

Urinary catheters are one of the major risk factors for developing a UTI in secondary care. UTIs associated with catheters are a leading cause of hospital-associated bacteraemia.

Clinical features

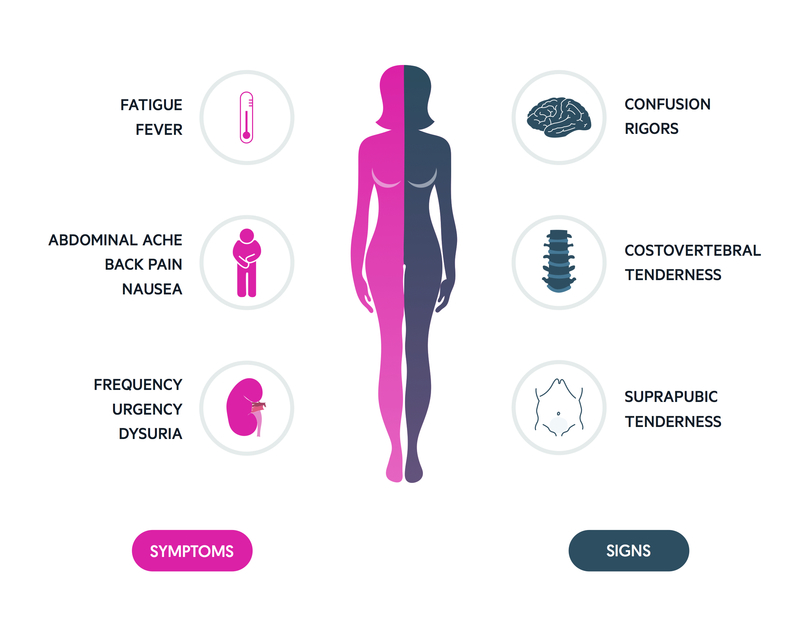

Typical clinical features of UTIs include dysuria (often described as burning) and increased frequency.

Dysuria is commonly described, women who suffer with recurrent UTIs will often identify the symptoms early. Clinicians should be alert for signs of pyelonephritis which include kidney pain, myalgia, fevers, rigors and nausea/vomiting.

Symptoms

- Dysuria

- Frequency

- Urgency

- Incontinence

- Suprapubic pain

- Haematuria

- N&V

Signs

- Fever

- Rigors

- Flank pain

- Confusion

- Costovertebral angle tenderness

Urosepsis

Urosepsis refers to a sepsis that originates from a urinary infection. Sepsis can be thought of as a dysregulated host response to infection leading to life-threatening organ dysfunction. Features include haemodynamic instability, tachypnea, changes to mental status, reduced urine ouput and pyrexia.

There are a number of scoring systems that can be used to assess risk and prognosis, each has their own limitations. An example is qSOFA (quick Sepsis Related Failure Assessment) that aims to identify patients at increased risk of poor outcomes outside the ITU environment. It consists of three components:

- Mental status (score 1 if altered mental status)

- Respiratory rate (score 1 if ≥ 22)

- Systolic BP (score 1 if ≤ 100)

Any patient with suspected sepsis should be managed with the SEPSIS-6 principles in mind. The sepsis six bundle is a protocol by which a patient may be investigated and treated for sepsis. It is by no means exhaustive but incorporates key investigation and treatment points. The bundle should be initiated and completed within one hour of recognition of the signs.

Patients with haemodynamic instability, a lactate greater than 2 or evidence of end-organ dysfunction (or any other reason for concern) should receive urgent review by a senior clinician and a MET/Peri-arrest call if indicated. All patients with significant infection should have a senior review.

Three In

Patients should receive high flow oxygen to achieve appropriate target saturations. A target of 94-98% is appropriate for the majority of patients. Those at risk of carbon dioxide retention (COPD) should have a target of 88-92%. IV fluids should be started, often 500ml of crystalloid over 15 minutes with reference the patient's haemodynamic status and co-morbidities. Antibiotics are key and should be given without delay, NICE recommend empirical treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam (tazocin).

Three out

A minimum of two sets of blood cultures should be taken. Ideally, this should happen prior to administration of antibiotics though they should not be a cause for delay. A serum lactate should be obtained normally via a blood gas (arterial or venous) to help assess the patient's status. Urine output should be measured ideally with a catheter with a careful fluid balance recorded.

Diagnosis & investigations

The definitive diagnosis of a UTI is based on typical clinical features associated with positive laboratory evidence of pyuria +/- bacteriuria.

In young, non-pregnant females, typical clinical features (e.g. dysuria, suprapubic pain) in the absence of vaginal symptoms, is highly suggestive of a UTI. In this patient group, the probability of a UTI is > 90%. Further laboratory testing offers little to the diagnosis, however as a minimum, the majority of clinicians would do a urine dip.

In the presence of complicating factors (e.g. systemic upset, diabetes, pregnancy, recurrent UTIs), further laboratory testing is necessary. Urinalysis, involving a urine dipstick and urinary microscopy, culture & sensitivity, (MC&S), is key.

Urine dipstick

A urine dipstick is useful to measure the presence of leucocyte esterase (an enzymes released by WBCs, which reflects pyuria) and nitrites. The latter is because common urinary tract pathogens are able to convert nitrate into nitrite.

The presence of both leucocytes and nitrites is strongly associated with a UTI, however, the absence of one or both of these findings does not rule out a UTI if there is still a high clinical suspicion.

Urinary MC&S

A urinary MC&S may identify the infecting microorganism and can help guide antibiotic sensitivities.

This is essential for patients with recurrent UTIs where resistance may have developed to previously used antibiotics.

Further investigations

Further testing involves the use of blood tests and radiological investigations. These may be warranted in those who do not respond to treatment, present with a severe infection, have an atypical infection or underlying co-morbidities.

A full blood count, urea & electrolytes and a CRP forms the basic screen of blood tests. They may show raised inflammatory markers and impaired renal function. The latter is particularly important to assess for the development of an acute kidney injury (AKI).

Radiological investigations are usually reserved for complicated pyelonephritis or uncomplicated UTIs that do not respond to conventional antibiotic therapy. It can include both ultrasonography and computed tomography. They are useful for the assessment of abscesses, haemorrhage, calculi, obstruction and emphysematous pyelonephritis.

Management

Management of UTIs involves the prescription of appropriate antibiotic therapy according to local guidelines and concordance with any culture results.

The choice of antibiotic, route of administration and duration of therapy is dependent on multiple factors. These may include sex, severity, sensitivities, infecting organism and response to treatment. Some example regimes are shown below.

In those presenting with features of sepsis, a full assessment including sepsis six (and any other investigations indicated by review) and senior review should be sought.

Uncomplicated

Acute uncomplicated UTIs can generally be managed with antibiotics such as trimethoprim or nitrofurantoin. The former should be avoided in pregnancy and the latter in renal impairment. A typical course of trimethoprim may be 200 mg BD for 3 days in women or 7-14 days in men. Nitrofurantoin is given at a dose of 50 mg QDS or 100 mg MR BD for 3 days in women or 7-14 days in men.

Acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis that does not require admission to hospital can be treated with a course of an oral fluoroquinolone such as 500 mg of ciprofloxacin 12-hourly for 14 days.

Complicated

Acute complicated cystitis may be treated with an oral course of a fluoroquinolone. In the presence of more severe disease (e.g. urosepsis) or patients unable to tolerate oral therapy, broad-spectrum IV antibiotics can be used.

Intravenous co-amoxiclav (e.g. 1.2 g 8-hourly, adjusted based on renal function) or ceftriaxone may be used for patients with urosepsis or acute severe pyelonephritis.

Catheter-associated UTIs

A urinary catheter or other indwelling catheter (e.g. suprapubic) is a major risk factor for the development of a UTI.

A catheter-associated UTI is diagnosed in the presence of bacteriuria (> 103 CFU/ml) of a uropathogenic organism in the presence of clinical features suggestive of a UTI without another possible source of infection.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is common in catheterised patients and as such the diagnosis should take the clinical picture into account.

Microorganisms causing catheter-associated UTIs are similar to those causing normal UTIs (e.g. E. coli most common). However, other species such as Enterococcus, Candida, Pseudomonas and Klebsiella should also be considered.

Treatment involves the use of appropriate antibiotic therapy as with all UTIs. Ideally, an infected urinary catheter should be removed or changed under antibiotic coverage.

Last updated: April 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback