COPD

Notes

Overview

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic respiratory disease, most commonly due to smoking-related lung damage.

COPD is a progressive, obstructive airway disease that is not fully reversible. It results from disease of the airways and parenchyma in the form of chronic bronchitis and emphysema.

- Chronic bronchitis: clinical term relating to a chronic productive cough for at least 3 months over two consecutive years. Alternative explanation for cough should be excluded (e.g. bronchiectasis).

- Emphysema: pathological term due to structural lung changes. Typically refers to abnormal airspace enlargement distal to terminal bronchioles with evidence of alveoli destruction and no obvious fibrosis. These characteristic changes can be detected on imaging (e.g. computed tomography).

COPD is extremely common, preventable and treatable in the majority of cases. This is because it occurs secondary to smoking-related damage.

The disease is very heterogenous with chronic airflow limitation resulting from a mixture of small airway disease (bronchitis) and destruction of the lung parenchyma (emphysema). The extent to which process is predominant differs from patient to patient.

Epidemiology

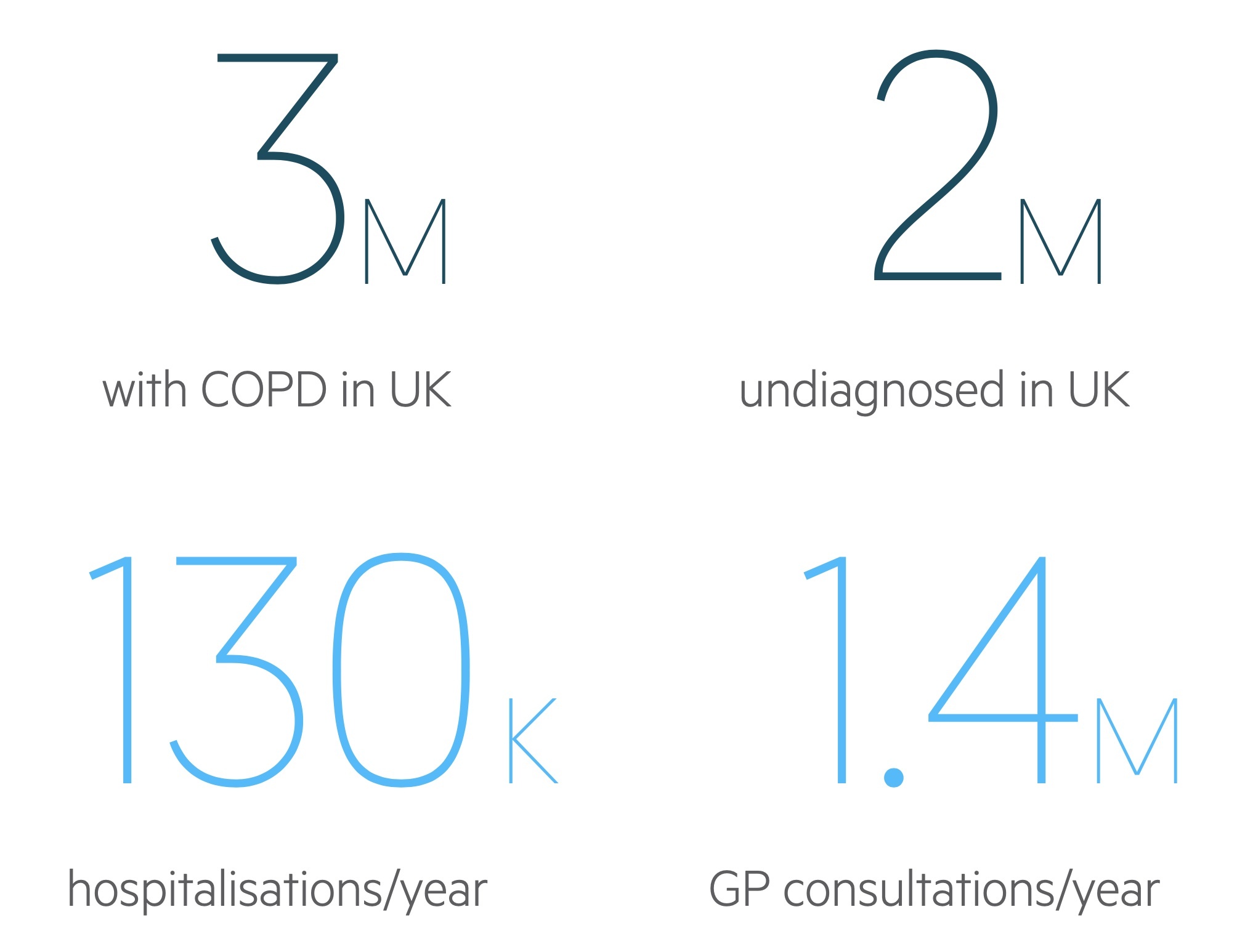

Approximately 3 million people in the UK are diagnosed with COPD and a suspected 2 million more may be undiagnosed.

COPD is a very common condition and accounts for a significant cause of morbidity and mortality within the UK.

- Consultations: accounts for ~1.4 million consultations with GPs each year

- Admissions: second leading cause for acute hospital admissions each year

- Deaths: remains one of the most common causes of death

The true prevalence of COPD is thought to be underestimated as many people remain undiagnosed. The condition predominantly affects adults > 40 years old and traditionally affected men at much higher frequencies. However, in more recent cohorts there is a similar sex prevalence.

Aetiology

Smoking is by far the most important aetiological factor.

Smoking

Approximately 90% of cases of COPD are associated with smoking. However, only 10% of smokers will develop it, indicating the presence of a co-factor such as a genetic predisposition. It is important to consider passive smoking and occupational pollutants in patients with COPD who are non-smokers.

In the absence of other co-factors, COPD is unlikely to develop in patients with a smoking history <10-15 pack years. Therefore, the key determinant in patients with suspected or confirmed COPD is smoking history, which is characterised by pack years.

Pack years = (number of cigarettes smoked per day, divided by 20, multiplied by the number of years smoked)

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder with co-dominant expression characterised by a deficiency in alpha-1 antitrypsin. It affects around 1 in 5000 in the UK.

Alpha-1 antitrypsin is a protease inhibitor that is synthesised by the liver. It acts in the lung parenchyma to oppose the action of elastase. Elastase is a protease that causes the breakdown of elastin, a protein important to the structural integrity of the alveoli. This causes emphysema.

Smoking increases the risk of these patients developing emphysema. Emphysema is characteristically panlobular with a lower zone predominance. This is compared to emphysema from smoking, which is characteristically centriacinar.

For more information see our notes on Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency.

Pathophysiology

COPD is a disease of both the airways and the alveoli.

Airways

Chronic bronchitis refers to inflammation of the bronchi, defined as a chronic productive cough for three (or more) months in two consecutive years where other causes are excluded. Pathologically it is characterised by chronic inflammation with neutrophilic infiltration, CD8+ T lymphocytes and macrophages. This differs from asthma, which has a predominant eosinophil infiltration with CD4+ T lymphocytes.

Chronic bronchitis leads to:

- Goblet cell hyperplasia

- Mucus hypersecretion

- Chronic inflammation and fibrosis

- Narrowing of small airways

Alveoli

Emphysema is the permanent enlargement of airspaces distal to the terminal bronchiole when interstitial pneumonias (e.g. interstitial lung disease & fibrosis) are excluded. Destruction of the lung parenchyma results in a reduced area for gas exchange and chronic hypoxia.

Inflammatory processes lead to the production of proteases by inflammatory cells such as macrophages and neutrophils. The protease elastase causes the destruction of elastin, a protein important to the structural integrity of the alveoli.

Loss of elastin has two effects:

- Collapse: the alveoli are prone to collapse.

- Dilation and bullae formation: alveoli dilate and may eventually join with neighbouring alveoli forming bullae.

Alpha-1 antitrypsin is a natural inhibitor of neutrophil elastase, which is reduced or absent in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, which predisposes to COPD.

Cor pulmonale

Cor pulmonale refers to right ventricular impairment secondary to pulmonary disease. In the developed world COPD is the most common cause.

Chronic hypoxia causes vasocontriction of pulmonary arteries, which leads to elevated pulmonary arterial pressure. The chronic elevation of pulmonary arterial pressure subsequently leads to right heart failure. This presents with classical features including raised jugular venous pressure, cyanosis, ankle oedema, parasternal heave and hepatomegaly.

Clinical features

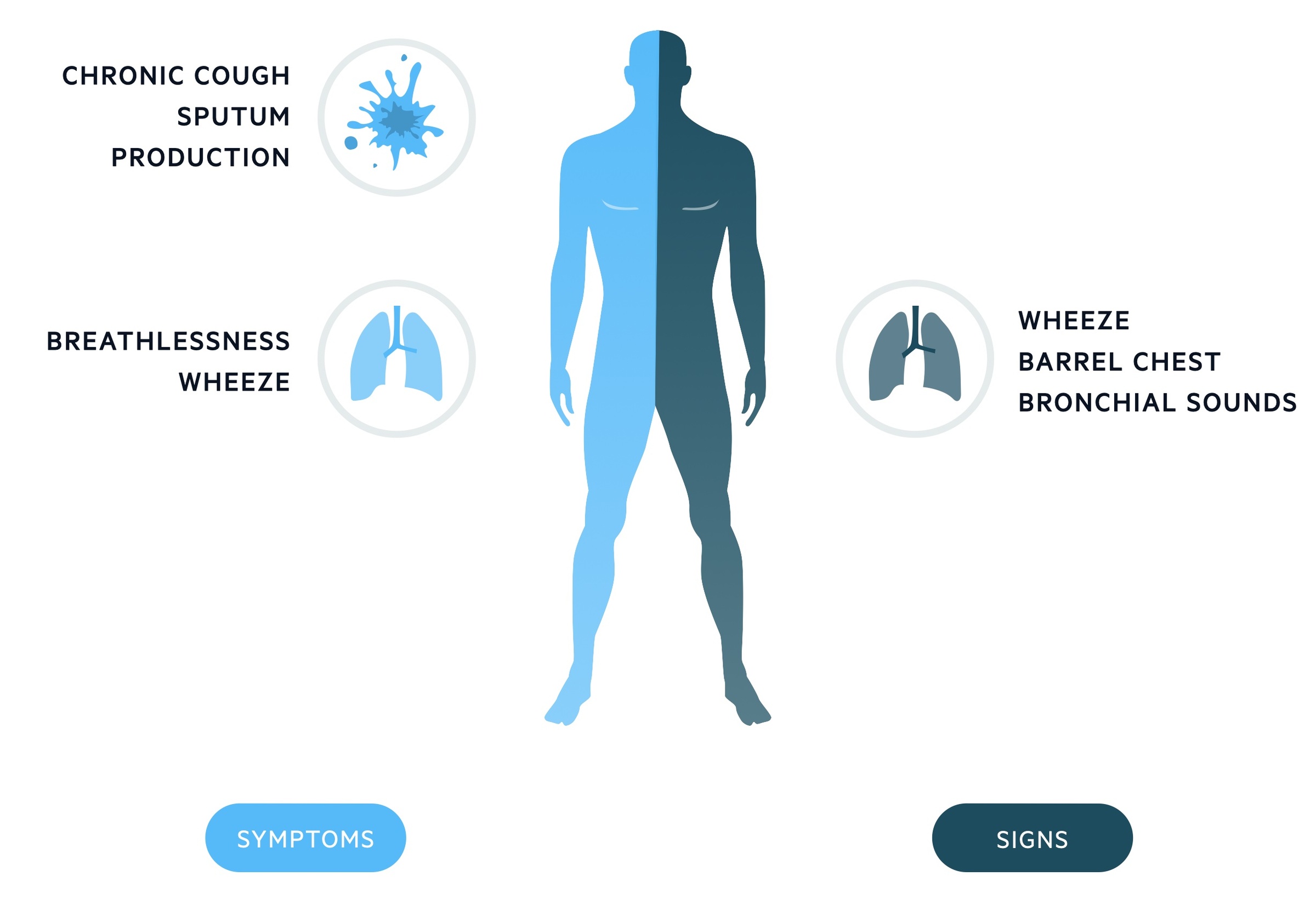

Chronic productive cough and dyspnea are the hallmarks of COPD.

Symptoms

- Chronic cough: usually productive

- Sputum production

- Breathlessness: usually on exertion in early stages

- Frequent episodes of 'bronchitis': usually in the winter

- Wheeze

Signs

- Dyspnoea

- Pursed lip breathing: (prevents alveolar collapse by increasing the positive end expiratory pressure)

- Wheeze

- Coarse crackles

- Loss of cardiac dullness: due to hyperexpansion of lungs from emphysema

- Downward displacement of liver: due to hyperexpansion of lungs from emphysema

- Signs of C02 retention

- Drowsy

- Asterixis

- Confusion

- Signs of cor pulmonale

- Peripheral oedema

- Left parasternal heave: caused by right ventricular hypertrophy

- Raised JVP

- Hepatomegaly

Concerning features

There may be clinical features in the history and on examination, which are suggestive of an alternative diagnosis such as lung cancer or pulmonary embolism. These require urgent investigation.

- Weight loss

- Haemoptysis

- Anorexia

- Chest pain

- Lymphadenopathy

- Finger clubbing

- Unexplained fatigue

Acute exacerbation

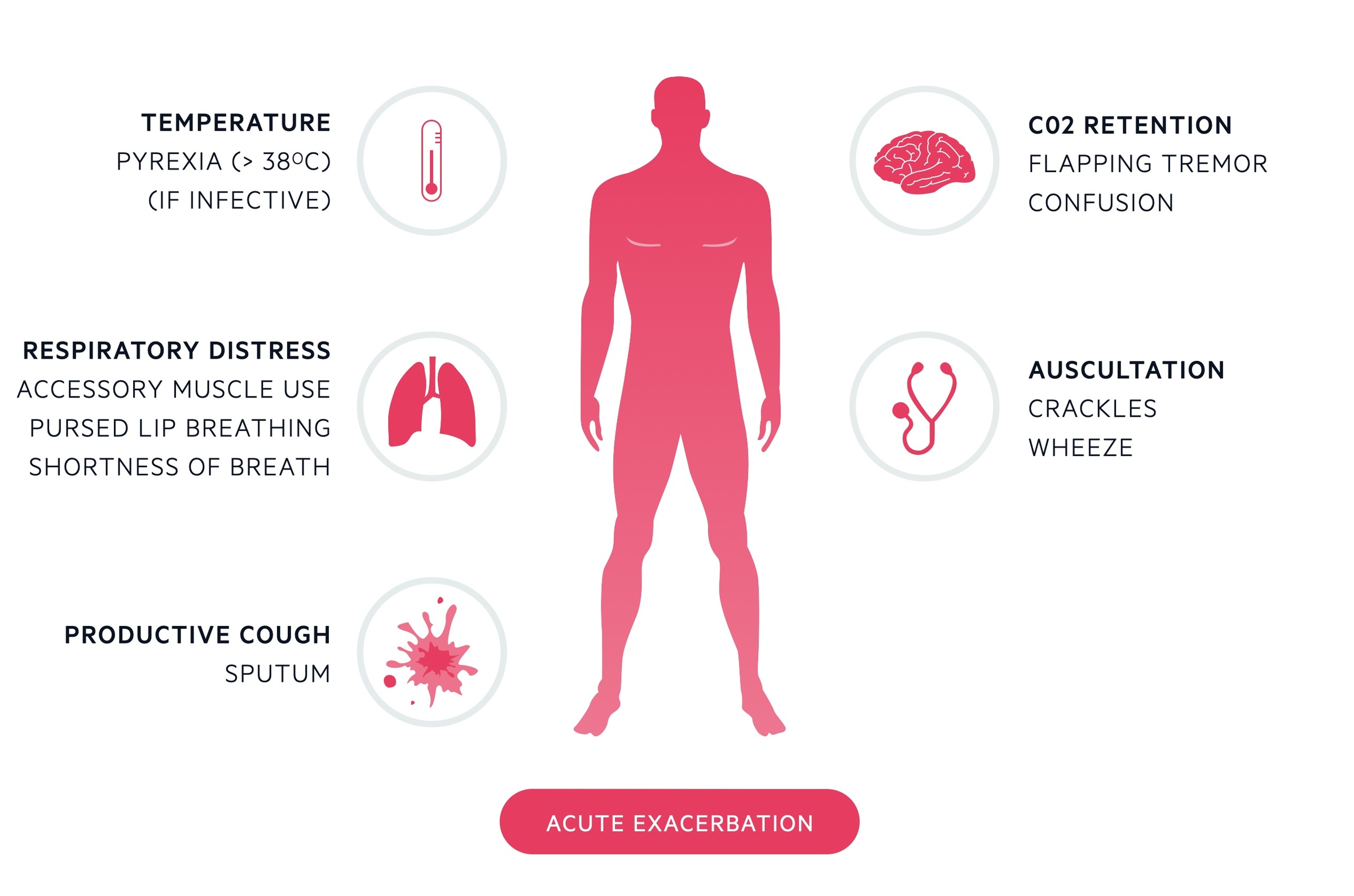

An acute exacerbation of COPD usually presents with similar features to chronic 'stable' COPD, which are listed above. The key is that an exacerbation refers to an acute, sustained worsening in the patients symptoms beyond the normal, expected, day-to-day variation.

An acute exacerbation may be mild, or life-threatening requiring hospital admission and respiratory support. Commonly, an exacerbation is driven by an underlying infection, but they can also be non-infective.

MRC dyspnoea scale

The Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale is used to grade the severity of breathlessness.

The MRC dyspnoea scale is divided from 1 to 5.

- Breathlessness on strenuous exercise.

- Breathlessness on hurrying or slight hill.

- Walks slower than contemporaries on ground level due to breathlessness OR have to stop to catch breath when walking at own pace.

- Stops to catch breath after 100 metres OR a few minutes of walking

- Breathlessness on minimal activity (dressing) or unable to leave the house due to breathlessness

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of COPD is suspected clinically, which is then confirmed by spirometry.

Typical clinical features (e.g. chronic cough, exertional breathlessness) in a patient with a significant smoking history is highly suggestive of COPD.

Patients with suspected COPD should be referred for spirometry to confirm the diagnosis.

Incidental findings

There may be evidence of COPD in patients undergoing imaging (e.g. chest radiograph, CT chest) for an alternative reason. CT usually shows evidence of emphysema. A chest x-ray will show flattening of the diaphragm, hyperinflation and there may be evidence of bullae. Patients with evidence of emphysema or chronic airway disease on imaging should be referred for spirometry assessment.

Spirometry

Spirometry is essential for both the diagnosis of COPD and to assess the severity.

Spirometry should be performed at the time of suspected diagnosis. It enables a formal diagnosis of airway obstruction consistent with COPD and enables assessment of the severity of airway obstruction.

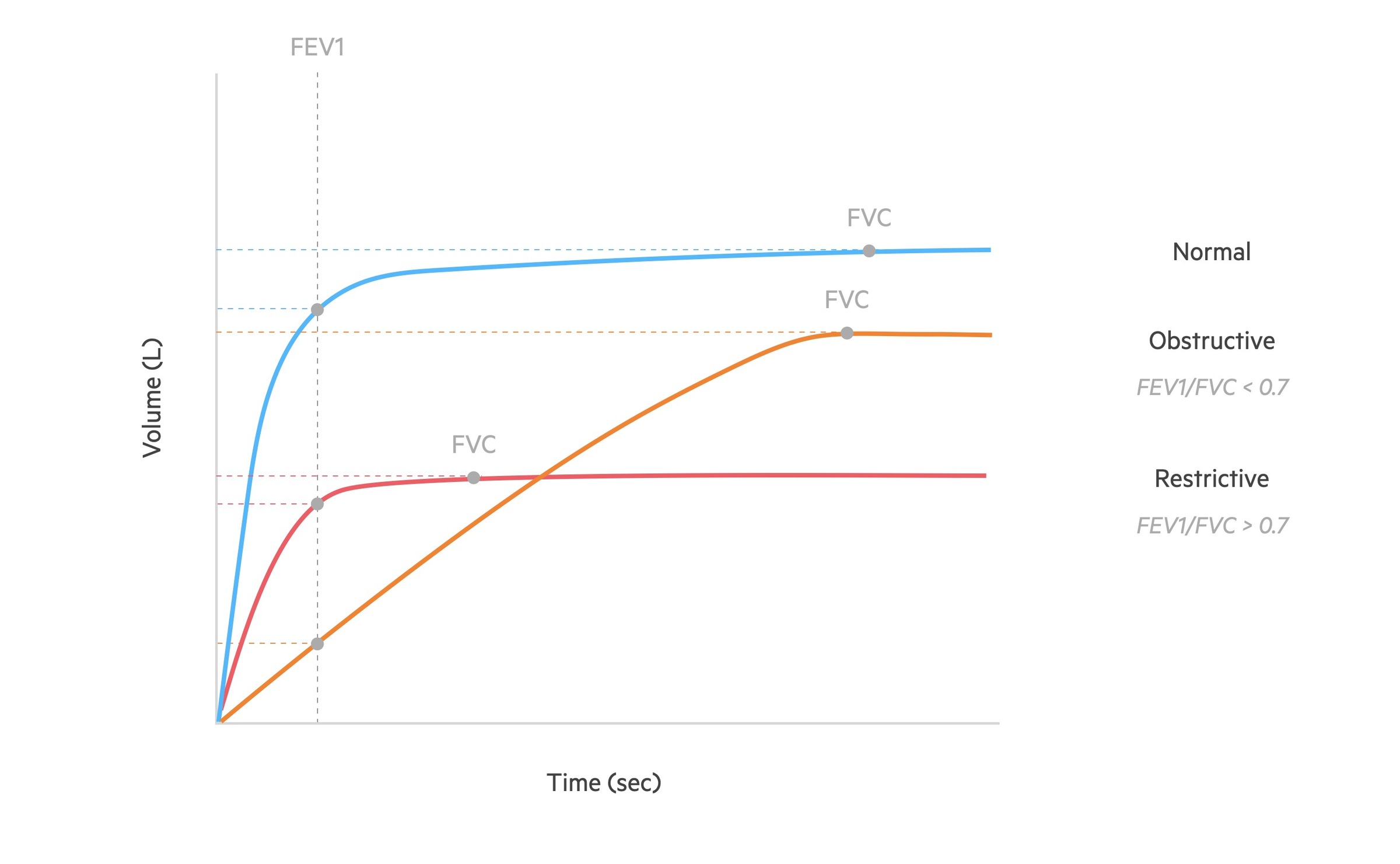

Spirometry measures the flow and volume of air during inhalation and exhalation:

- FVC: the forced (expiratory) vital capacity is a persons maximal expiration following full inspiration.

- FEV1: the forced expiratory volume in one second, i.e the volume of FVC expelled after one second.

The following changes are seen in obstructive lung disease (orange line):

- FVC: may be normal but often reduced due to air trapping.

- FEV1: reduced

- FEV1/FVC: < 70%

Spirometry diagnosis

Typical clinical features of COPD with a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.7 is consistent with a diagnosis of COPD.

As part of spirometry, reversibility testing may be completed that assesses spirometry measurements following inhalation of a bronchodilator (e.g. beta-agonist). COPD is characterised by limited reversibility post-bronchodilator, which helps differentiate it from asthma. Reversibility is a hallmark of asthma. Routine reversibility testing may not be necessary, especially for the initial diagnosis of COPD because it is usually distinguishable based on history and examination.

Features supportive of COPD (versus asthma) include:

- Smoker or ex-smoker

- Symptoms in older adults (> 35 years old)

- Chronic productive cough

- Persistent/progressive breathlessness

- Night time waking with symptoms uncommon

- Variability uncommon (diurnal or day-to-day)

In patients with an FEV1/FVC < 0.7 but without typical features of COPD, an alternative diagnosis should be considered (e.g. bronchiectasis).

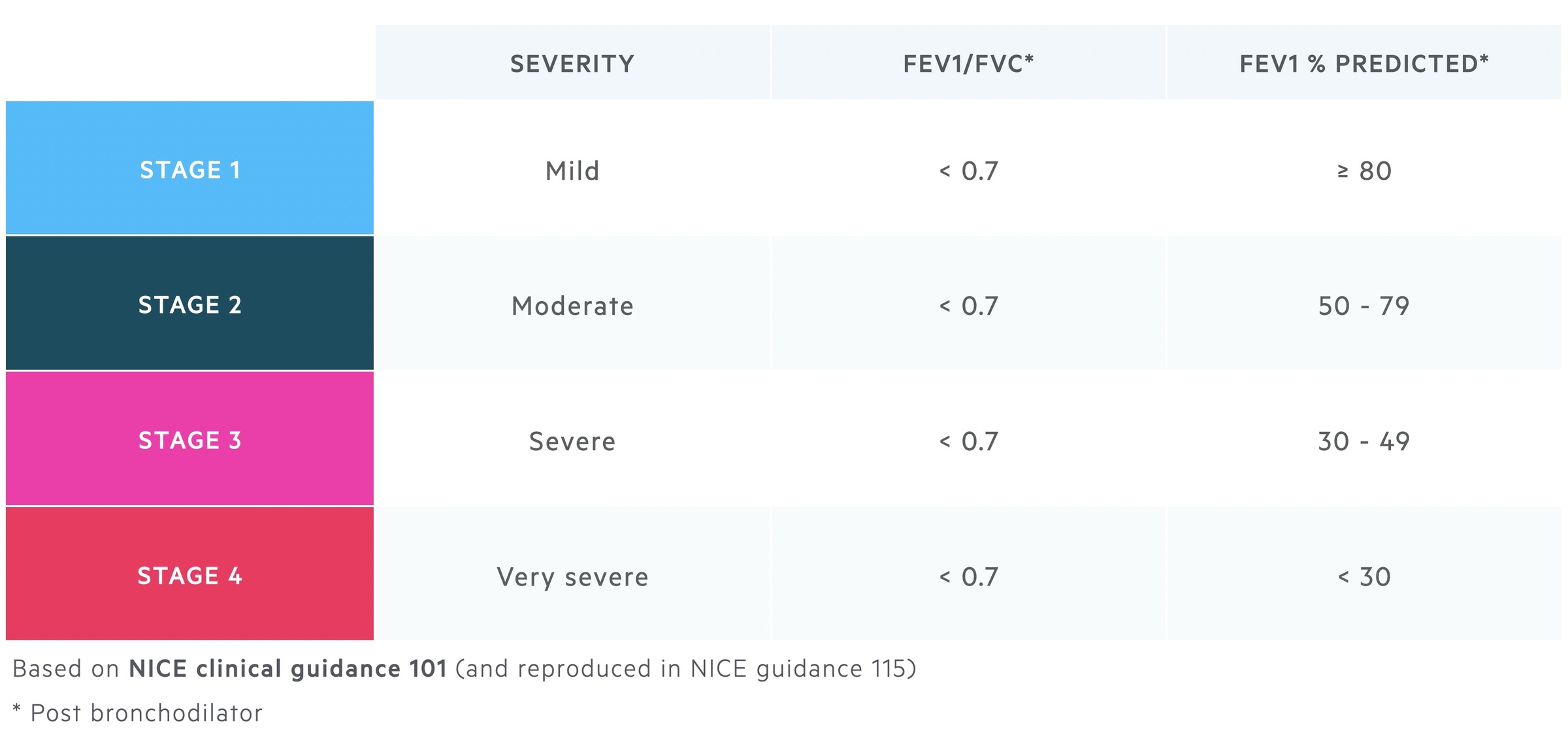

Severity

Spirometry may be used to assess the severity of COPD.

Following confirmation of a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.7, severity can be determined by the predicted FEV1 %. The predicted FEV1 % refers to how the patients' FEV1 compares to the average FEV1 in a population of similar age, sex and body composition. There are standard formulas available to determine the predicted FEV1 for men and women at different ages. This is then used alongside the patients' FEV1 to work out the predicted FEV1 %.

Using the predicted FEV1 %, the NICE CG12 (2004) guidelines, America thoracic society/European respiratory society (2004) guidelines, GOLD (2008) guidelines or NICE CG101 (2010) guidelines can all be used to grade the severity of COPD.

Below we show the severity of COPD based on the NICE clinical guidance 101 and reproduced in the updated NICE guidance 115.

Investigations

At the time of diagnosis, all patients require a chest radiograph, full blood count and body mass index calculated.

Bedside

- Observations: including pulse oximetry

- Body mass index (BMI)

- Sputum culture (if purulent)

- Arterial blood gas (if hypoxia or hypercapnia is suspected): needed in acute exacerbations or work-up for long-term oxygen therapy

- ECG (if cor pulmonale suspected)

Bloods

- Full blood count: important to assess for anaemia and polycythaemia

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin levels

Additional blood tests (e.g. urea & electrolytes, C-reactive protein) may be required during an acute exacerbation.

Imaging

- Chest x-ray (CXR):

- Hyperexpanded

- Flattened hemidiaphragms

- Hypodense

- Saber-sheath trachea

- CT scan: consider performing if

- Symptoms disproportionate to spirometric assessment

- Alternative diagnosis suspected (e.g. bronchiectasis, fibrosis)

- Lung cancer suspected or to investigate abnormalities on chest x-ray

- Echocardiogram: if cor pulmonale suspected.

CXR demonstrating COPD with hyperinflation

Image courtesy of Assoc Prof Frank Gaillard, Radiopaedia.org

Specialist referral

Many patients with COPD can be managed in general practice without need for specialist referral.

Patients with mild or moderate COPD may be managed in general practice without need for specialist referral, which includes assessment by a respiratory clinical nurse specialist.

Indications for specialist referral to a clinician or nurse specialising in respiratory disease include:

- Diagnostic uncertainty

- Severe COPD (FEV1 < 50%)

- Cor pulmonale

- Assessment for specialist therapy (i.e. long-term oxygen therapy or nebuliser therapy)

- Bullous disease

- Rapid decline in FEV1

- Assessment for surgical intervention (i.e. lung reduction surgery, transplantation)

- Assessment for pulmonary rehabilitation

- Others

Management principles

All patients with COPD should be offered education, smoking cessation, vaccinations, pulmonary rehabilitation (if indicated) and pharmacotherapy (e.g. inhalers).

It is important to review and revisit the principles of COPD care at all stages of severity and during every consultation.

The principles of COPD care include:

- Education

- Smoking cessation

- Vaccination

- Pulmonary rehabilitation

- Self-management plans

- Management of co-morbidities

- Pharmacotherapy

Education

It is important to educate patients about their condition and check inhaler technique at every consultation.

Smoking cessation

All patients should be encouraged to stop smoking, offered nicotine replacement therapies and/or referred to smoking cessation services.

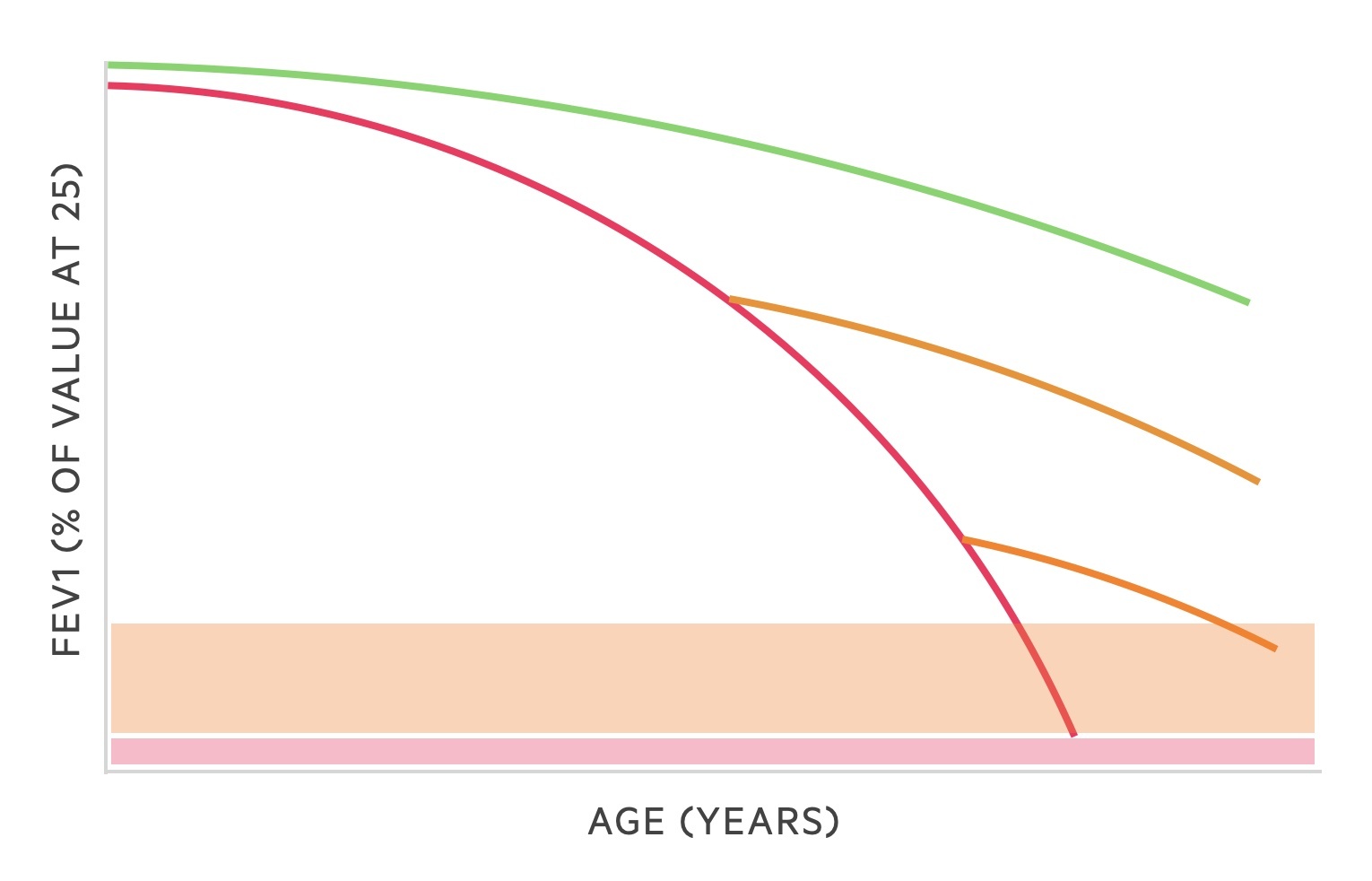

The Fletcher and Peto graph shows the effects of smoking cessation. The green line follows the normal trajection of a healthy individuals FEV1 as they age. The red line shows the trajection of a smoker. The orange lines show the effect of smoking cessation - the FEV1 begins to fall at the rate of a non-smoker though existing damage is not reversed.

Vaccination

Patients with COPD should be offered the seasonal influenza vaccine and the pneumococcal vaccine.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

This refers to a multidisciplinary programme that aims to optimise the physical and social performance of patients suffering from long-term chronic lung conditions like COPD. It involves exercise training, health education, and breathing techniques over a series of sessions. Nutritional education and behavioural techniques are also utilised.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is offered to any patient with COPD who feels disabled by their condition. It is not suitable in patients unable to walk, who have unstable angina or have recently suffered a heart attack.

Self-management plans

This refers to helping patients manage their symptoms including how to manage acute exacerbations. Education is crucial and patients are often provided with a 'rescue pack' that contains antibiotics and steroids.

Managing co-morbidities

Patients with COPD may have complications of their disorder (e.g. right heart failure) or have other smoking-related illnesses such as ischaemic heart disease, heart failure or cancer. It is important to optimise their co-morbidities to help improve their clinical symptoms. For example, heart failure and anaemia may exacerbate breathlessness symptoms that could be wrongly attributed to COPD.

It is also important to recognise features of anxiety and depression, which commonly worsen symptoms of COPD.

Pharmacotherapy

Inhalers form the backbone of medical therapy for the treatment of COPD. Steroids and antibiotics are commonly used for acute exacerbations and long-term oxygen therapy may be needed in severe cases. These are discussed below.

Managing stable COPD

Inhaled therapies form the cornerstone of management in COPD.

Inhaled therapy

There are many different inhalers that can be used in the treatment of COPD. Inhalers may contain a single drug (e.g. beta-agonist) or combination of drugs (e.g. beta-agonist and corticosteroid).

Drug classes

- Beta-receptor agonists: bind to beta receptors of the sympathetic nervous system. Causes relaxation of airway smooth muscle and subsequent bronchodilation. May be short or long-acting.

- Muscarinic receptor antagonists: these drugs prevent the activation of muscarinic receptors by acetylcholine. This prevents airway smooth muscle contraction and causes bronchodilation. Can be short or long-acting.

- Corticosteroids: inhaled corticosteroids work by reducing inflammation within the lungs. They are thought to reduce the number of exacerbations, improve the efficacy of bronchodilators and decrease dyspnoea in stable COPD.

Inhaler types

- Short-acting beta-agonists (SABA): Salbutamol

- Long-acting beta-agonists (LABA): Salmeterol

- Short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SAMA): Ipratropium

- Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA): Umeclidinium / tiotropium

- Inhaled corticosteroid (ICS): Beclomethasone

- LABA-ICS: Seretide (salmeterol/fluticasone)

- LABA-LAMA: Ultibro (indacaterol/glycopyrronium)

- LABA-LAMA-ICS: Trimbow (formoterol/glycopyrronium/beclometasone)

Delivery devices

Inhalers may deliver drugs by different mechanisms

- Metered dose inhalers (MDI): delivers a specific amount of medication to the lungs by a short burst of aerosolised medicine. Patient dependent, requires good breath and coordinating activation with breath. Many patients have poor technique.

- Dry powder inhaler (DPI): usually requires 'loading' or 'activation' of the device for the powder to be administered. Requires good force of patient inhalation and need to hold breath for certain period.

- Soft mist inhaler (SMI): contain liquid formulations of the drug. More drug delivery to lungs and less coordination needed compared to MDI inhalers.

- Spacers: typically used with a MDI inhaler to enhance drug delivery and reduce need for good coordination. Contains a chamber that the drug is delivered into and the patient then completes normal tidal breathing to inhale the drug.

- Nebuliser: drug in liquid form is converted into a mist using a nebuliser machine with compressed air. Typically reserved for patients with an acute exacerbation in hospital or disabling symptoms despite maximal inhaler therapy.

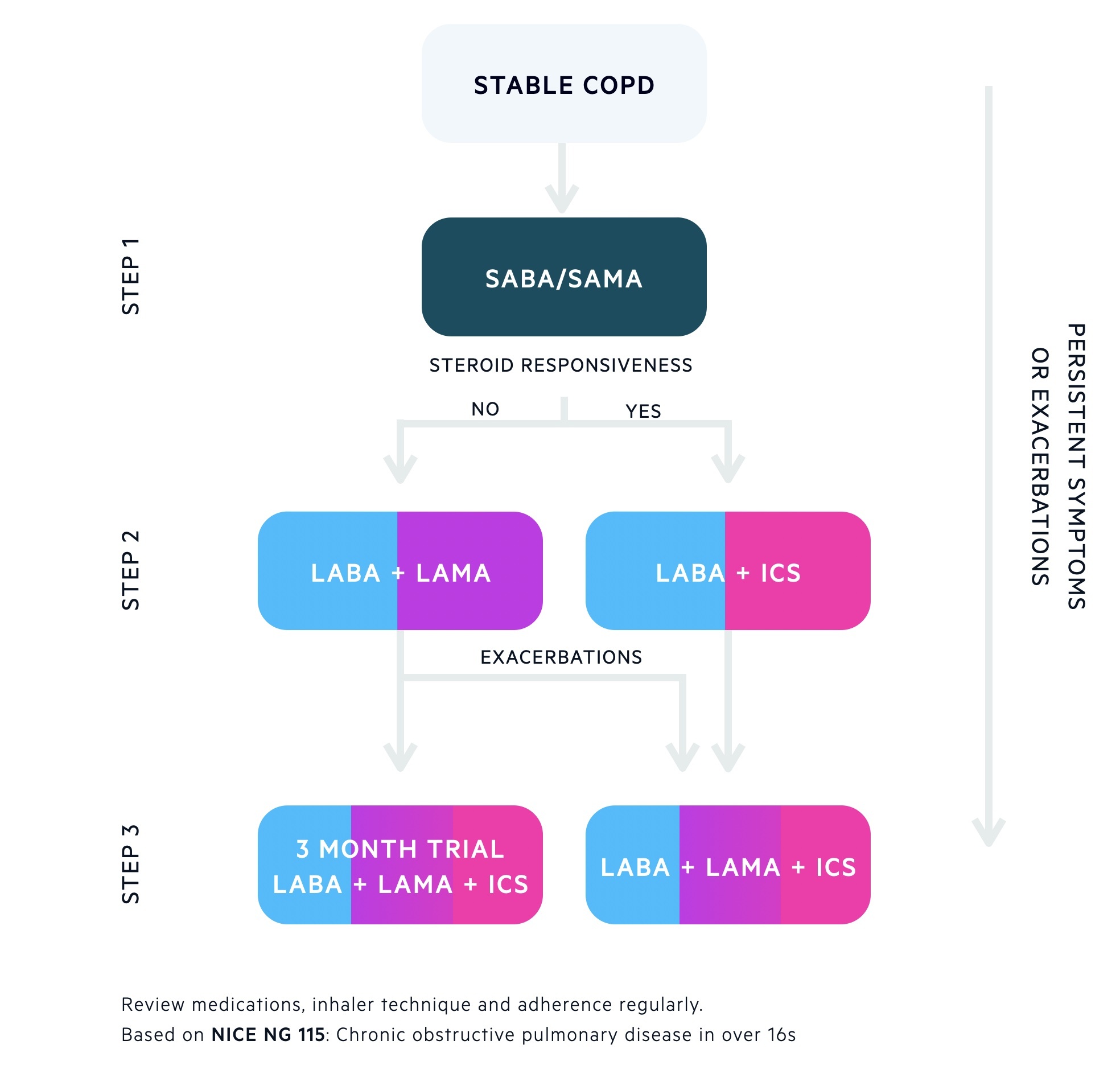

Stepwise management

Inhaled therapy should be offered to patients with persistent symptoms despite basic interventions (e.g. smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation, self-management). This should be revisited before each escalation of therapy.

- First step

- Offer a SABA or SAMA for patients to use on a PRN basis

- Second step (Ongoing symptoms despite SABA/SAMA or acute exacerbations)

- Offer LABA+LAMA if no evidence of steroid responsiveness or asthmatic features), OR

- Offer LABA+ICS if evidence of steroid responsiveness or asthmatic features

- Third step: offer escalation to triple therapy (LABA + LAMA + ICS)

- Option 1 (already on LABA + LAMA): 3 month trial of triple therapy if clinical features impact quality of life. If no improvement, revert back to LABA + LAMA only

- Option 2 (already on LABA + LAMA): offer triple therapy if 1 severe or 2 moderate acute exacerbations within one year.

- Option 3 (already on LABA + ICS): offer triple therapy if clinical features impact quality of life or 1 severe or 2 moderate acute exacerbations within one year.

If ongoing symptoms or acute exacerbations despite optimal inhaled therapy explore oral treatment options, nebulisers and consider assessment for LTOT.

Oral therapy

There are several oral pharmacological options that may be offered to patients with COPD.

- Corticosteroids: these form the mainstay of treatment in acute exacerbations. Rarely they are used long-term in patients with advanced COPD if they cannot be withdrawn after an acute exacerbation.

- Theophylline: some bronchodilator action through inhibition of phosphodiesterase. May be used in difficult to treat COPD. Many interactions and requires monitoring levels. At risk of toxicity.

- Mucolytics: can be used in patients with a chronic productive cough to reduce frequency of cough and sputum production (e.g. carbocisteine). Breaks disulphide crosslinks between mucin monomers.

- Antibiotics: commonly used for acute exacerbations. May be used prophylactically in certain situations (e.g. azithromycin). Should be initiated by specialists.

Surgical intervention

Rarely, surgical intervention may be offered to some patients. Surgical options include:

- Lung reduction surgery

- Bullectomy

- Lung transplantation

Managing acute exacerbations

Patients with an acute exacerbation of COPD often require admission to hospital for treatment.

An acute exacerbation of COPD refers to a sustained worsening of a patients clinical symptoms above and beyond the normal day-to-day variation. Some patients may be managed at home whereas others can be critically unwell needing hospital admission and non-invasive ventilation.

Common clinical features of an acute exacerbation include:

- Worsening breathlessness

- Worsening cough

- Increased sputum production

- Change in sputum colour

Inpatient versus outpatient

Deciding on whether a patient requires admission to hospital for treatment of an acute exacerbation of COPD should take into account different factors.

Factors that support hospital admission include:

- Inability to cope at home

- Severe clinical symptoms: severe breathlessness, cyanosis, evidence of heart failure, acute confusion or low saturations (<90%)

- Severe co-morbidity (e.g. diabetes on insulin or cardiac disease)

- Poor level of activity (e.g. confined to bed)

- Already receiving LTOT

- Chest radiograph changes

Basic investigations

All patients admitted to the hospital with an acute exacerbation of COPD require the following investigations:

- Chest x-ray

- Arterial blood gas (ABG)

- Electrocardiogram (ECG)

- Bloods: FBC, U&E, CRP

- Cultures: Blood (if pyrexial), sputum

- Theophylline levels (if part of admission medications)

Acute management

All patients with an acute exacerbation of COPD should initially be managed with an 'airway, breathing, circulation' approach as they can be critically unwell.

If there is any concerns about the airway, level of consciousness or there are features of respiratory failure then senior support should be sought immediately.

Exacerbations are treated with:

- Oxygen: this should be used cautiously in patients with COPD. Venturi masks allow an exact fraction of inspired oxygen to be administered. If there is any known or new evidence of carbon dioxide retention then a saturation target of 88-92% should be used (high PaCO2 on ABG or high bicarbonate indicating chronic compensation). Patients who need high levels of oxygen to prevent hypoxia but are at high risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure (Type 2 failure) often require non-invasive ventilation.

- Bronchodilators: usually given as nebulisers, but handheld devices can be used as an alternative if well enough.

- Salbutamol (beta-agonist) 2.5 mg nebulised: can be given back-to-back initially. Once stabilised, usually given four times per day with additional PRN doses as needed

- Ipratropium (muscarinic antagonist) 500 mcg nebulised: can be given as a STAT dose with salbutamol, then given 2-4 times per day.

- Corticosteroids: prednisolone 30 mg once daily should be given for 5 days unless there is a significant contraindication

- Antibiotics: local antibiotics guidelines should be followed for the use of antibiotics. Typical options include doxycycline or co-amoxiclav. If there are chest x-ray changes, patients should be treated with antibiotics for pneumonia.

Intravenous theophylline may be considered in severe cases, which do not improve with standard treatment (i.e. nebulisers). Requires cardiac monitoring. Senior advice should always be sought.

Type II (hypercapnic) respiratory failure

Patients with COPD are at risk of developing type II respiratory failure (T2RF) i.e. PaO2 < 8 kPa and raised PaCO2 (above reference range). For more information see Respiratory failure notes.

Oxygen therapy must be used carefully in patients with COPD, typically saturations of 88-92% are targeted. ABGs may be necessary to monitor for CO2 retention.

If patients have evidence of T2RF, oxygen therapy should be trialed using a venturi mask for 1 hour with repeat ABG. If there is persistent evidence of T2RF, or they decline during the trial period, then non-invasive ventilation should be considered (i.e. BiPAP). BiPAP refers to Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure, which helps to 'blow off' excess carbon dioxide and normalise pH.

Indications for BiPAP:

- Acute or acute on chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure (not requiring tracheal intubation)

- pH < 7.35

- PCO2 > 6

- Increased RR despite optimisation of oxygen therapy

- Cardiogenic pulmonary oedema (refractory to CPAP - continuous positive airway pressure)

- Type 1 respiratory failure and clinically tiring

- Weaning from mechanical ventilation

Patients requiring BiPAP should be managed in a high-dependency unit (HDU) setting or a specialist ward with nurses who are able to look after patients receiving BiPAP. Moreover, before starting BiPAP it is crucial to discuss and set ceilings of care (often involves discussion with ITU), to exclude any contraindications (e.g. undrained pneumothorax, coma, facial trauma/burns, cardiovascular instability) and plan to continually monitor.

There are two settings on a BiPAP machine:

- IPAP: inspiratory positive airway pressure (usually 10-15 cmH20)

- EPAP: expiratory positive airway pressure (usually 4-5 cmH20)

The difference between the IPAP and EPAP is crucial to blow off carbon dioxide. Patients are typically started on 12/5 and a repeat ABG is completed after one hour, which guides response to therapy.

Further information on BiPAP and NIV is beyond the scope of these notes.

Long-term oxygen therapy

Patients with COPD may benefit from long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT).

Long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) is reserved for patients who meet the following criteria:

- Arterial Pa02 < 7.3 kPa, OR

- Arterial Pa02 < 8 kPa with any of:

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Peripheral oedema

- Secondary polycythaemia

LTOT is required for at least 15 hours a day for a benefit to be seen. Patients who smoke should be explained the dangers of mixing oxygen and cigarettes.

Complications

COPD is a major cause of mortality within the UK.

Exacerbations of COPD are a frequent cause of hospital admission, particularly in the winter months when respiratory pathogens are prevalent.

Common complications associated with COPD include:

- Respiratory failure

- Pneumonia: often recurrent

- Pneumothorax: rupture of bullous disease

- Polycythaemia or anaemia

- Depression

Last updated: September 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback