Pneumonia

Notes

Definition & classification

Pneumonia is the inflammation of the parenchyma of the lung.

Pneumonia is a common type of infection affecting the lung tissue (i.e. parenchyma). In pneumonia, the air sacs (i.e. alveoli) become filled with microorganisms and inflammatory cells leading to poor lung function with features of cough, fever, and shortness of breath. Pneumonia can be life-threatening, particularly in frail, elderly patients or those who are immunosuppressed. Pneumonia is one of several types of respiratory infections, which include:

- Upper respiratory tract infection (URTI): inflammation of the mucosa of the nostrils, nasal cavity, mouth, throat (i.e. pharynx), and larynx. Colloquially known as the ‘common cold’

- Lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI): refers to inflammation of the lower airways. This includes bronchitis, pneumonia and exacerbation of COPD.

- Pneumonia: inflammation of the lung parenchyma with the normal air-filled lungs becoming filled with infective liquid (known as consolidation)

The most common cause of pneumonia is infection and the majority of these are bacterial in nature. Viruses, fungi, and parasites may also cause pneumonia.

Bacteria may reach the lungs via one of three routes:

- Inhalation

- Aspiration

- Haematogenous

These infections may result in both pulmonary and extrapulmonary symptoms. Diagnosis often involves demonstrating acute consolidation on a chest radiograph but may require testing for a specific organism.

Pneumonia may be divided into groups based on the location it was contracted, comorbidities, and the immune status of the patient. This helps to identify the likely causative organism and guide management.

Community-acquired

CAP is a pneumonia that is contracted in the community. It has as traditionally been divided into typical and atypical pneumonia.

In essence, CAP refers to pneumonia contracted outside of the hospital setting and includes those developing the condition in a nursing home.

Typical pneumonias

These tend to present with features 'typical' of pneumonia; a productive cough, fever and pleuritic chest pain. Likely infecting organisms include:

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (most commonly)

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Moraxella catarrhalis

Atypical pneumonias

These tend to have a more insidious, subacute onset. They often present with a combination of pulmonary and extrapulmonary symptoms. Likely infecting organisms may be divided into nonzoonotic and zoonotic causes:

- Nonzoonotic: Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Chlamydophila pneumoniae

- Zoonotic: Chlamydophila psittaci (psittacosis), Coxiella burnetii (Q fever), Francisella tularensis (tularemia).

Hospital-acquired

HAP is defined by NICE as a pneumonia contracted > 48 hrs after hospital admission that was not incubating at the time of admission.

Patients in hospital adopt the local bacterial environment, one that differs from what is encountered in the community. This is known to persist for a number of weeks following discharge. Likely organisms include:

- Gram-negative bacilli (e.g. Pseudomonas aeruginosa)

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Legionella pneumophila

Aspiration

Aspiration pneumonias are caused by the inhalation of oropharyngeal or gastric contents. This brings bacteria found in these environments into the lungs.

Aspiration pneumonias have typically been associated with patients who are unable to adequately protect their airway, it may be seen in patients with:

- Reduced conscious level

- Neuromuscular disorders

- Oesophageal conditions

- Mechanical interventions such as endotracheal tubes.

It is increasingly recognised that many CAPs and HAPs may result from an otherwise inconsequential aspiration event. Studies have shown hospitalised patients on proton-pump inhibitors are more at risk of developing HAP than those who are not, implicating aspiration in the aetiology.

Infective organisms include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Enterobacteriaceae, in the hospital Gram-negative bacilli (e.g. pseudomonas aeruginosa) is more likely to be implicated.

NOTE: Mendelson’s syndrome is a related condition, It is defined as a chemical pneumonitis caused by aspiration of acidic gastric contents classically seen by obstetric anaesthetists.

Immunocompromised

Patients with pathological and iatrogenic immunosuppression are at risk of infective organisms not usually seen in other patient groups.

We consider a wider range of likely causative organisms in immunocompromised patients:

- Bacterial pathogens: as discussed as well as the mycobacterium complex and non-tuberculosis mycobacterium.

- Fungal pathogens: such as Pneumocystis jirovecii, Aspergillus fumigatus and Cryptococcus neoformans.

- Viral pathogens: such as varicella zoster virus and cytomegalovirus should be considered.

- Parasitic pathogens: parasitic pneumonias are very rare and seen almost exclusively in the immunocompromised.

Organisms

Numerous organisms may be responsible for a pneumonia, below a few common organisms are discussed.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a gram-positive alpha-haemolytic streptococci. It is the most common cause of CAP (classically lobar), presenting with a cough, pleuritic pain and pyrexia. It frequently causes a significant leucocytosis and a raised CRP.

It classically gives rust coloured sputum and may be accompanied by the reactivation of cold sores. Urinary antigen tests may be used to diagnose the infection and is unaffected by antibiotics.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a rod-shaped bacterium that lacks a cell wall. It tends to affect a younger demographic and occurs in cyclical epidemics.

It causes a pneumonia with a prolonged, insidious onset that may exhibit extrapulmonary features. Extrapulmonary features include:

- Erythema multiforme

- Arthralgia

- Myocarditis, pericarditis

- Haemolytic anaemia

Diagnosis can be made with serology.

Legionella pneumophila

L. pneumophila is a gram-negative coccobacillus that may cause the atypical CAP (typically lobar) Legionnaire’s disease. It is encountered in those exposed to contaminated cooling systems, humidifiers and showers. Chest symptoms may be preceded by several days of myalgia, headache and fever.

Hyponatraemia, secondary to SIADH, is a classical finding in Legionnaire’s disease but is not always present. Other biochemical abnormalities include hypophosphataemia and raised serum ferritin.

Diagnosis may be made with urinary antigen testing (for serogroup 1). Cultures of respiratory secretions and PCR may also be used.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

P. aeruginosa is a gram-negative bacillus that typically HAP. In patients with bronchiectasis (e.g. cystic fibrosis) is may cause CAP. It is often described as an opportunistic pathogen, rarely causing disease in healthy individuals. Typically it causes pneumonia in immunosuppressed patients and those with chronic lung disease. It should be remembered it may affect many of the bodies systems independent of the lungs and can lead to a bacteraemia.

It tends to cause the symptoms classically associated with pneumonia. Sputum is characteristically green. Delineating between active infection and incidental airway colonisation can be difficult. Bronchoalveolar lavage may be used to obtain samples. Treatment often involves a cephalosporin and aminoglycoside. Aerosolised antibiotics may be used in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Klebsiella pneumophila

K. pneumophila is a gram-negative bacillus that classically causes CAP classically seen in alcoholics. It causes a fast moving lobar pneumonia. Symptoms include a cough, fever and flu-like features. Sputum may have the characteristic ‘red-currant jelly’ appearance.

K. pneumophila shows resistance to beta-lactams. Beta-lactamase stable beta-lactams, cephalosporins and aminoglycosides may be used to treat the infection.

Pneumocystis jirovecii

Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly PCP/ pneumocystis carinii), a fungi, is an AIDS-defining illness that may cause a life-threatening pneumonia. It causes fever, cough (frequently non-productive) and exertional dyspnoea. Hypoxia and a raised LDH are also common findings.

It may be diagnosed with sputum stains though bronchoalveolar lavage may be required to obtain samples. It is now classified as a fungi though was previously described as a protozoa. It does not respond to antifungals and is instead treated with co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole).

Clinical features

Pneumonia is often characterised by cough, SOB, and the signs of consolidation. In atypical pneumonias extrapulmonary features may predominate.

Symptoms

- Fever

- Malaise

- Cough (purulent sputum)

- Dyspnoea

- Pleuritic pain

Signs

- Dull percussion note

- Reduced breath sounds

- Bronchial breathing (transmission of bronchial sounds to peripheries due to consolidation)

- Coarse crepitations

- Increased vocal fremitus (increased transmission of ’99' through consolidated lung)

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Confusion

- Cyanosis

Complications

The course of a pneumonia may be interrupted by any of a number of complications.

- Pulmonary complications:

- Parapneumonic effusion

- Pneumothorax

- Abscess

- Empyema

- Extrapulmonary complications:

- Sepsis

- Atrial fibrillation

Investigations & diagnosis

Investigations should not delay antibiotic treatment which should be administered within 4 hours of admission or diagnosis (and < 1 hour where sepsis is suspected).

Bedside

- Observations

- Sputum sample

- Urinary sample:

- Microscopy, Culture and Sensitivity (MC&S): Consider to exclude urinary source of infection

- Urinary antigens: Consider pneumococcal and legionella urinary antigen tests to help guide antibiotics

- ECG

Bloods

- Full blood count (FBC)

- Urea & electrolytes (U&Es)

- CRP

- Blood cultures

For patients presenting to their GP, NICE (NG 191) advise considering a point of care CRP where diagnosis is uncertain or unclear whether antibiotics are indicated.

Imaging

- Chest x-ray: often diagnostic showing consolidation though findings may lag behind onset and remain following resolution. May also show parapneumonic effusions, pneumothorax, abscess and empyema.

Right middle lobe pneumonia

Image courtesy of Dr Sajoscha Sorrentino and Radiopaedia.org

CRB-65 & CURB-65

CRB-65 and CURB-65 are scoring systems that help stratify patients risk of mortality and determine the best place of care.

Each category is worth one point when present. Confusion may be defined as an AMT < 8 (abbreviated mental test) or new-onset disorientation in time, place or person.

CRB-65

The CRB-65 is an aid to clinical judgement that helps to assess the need for hospital admission. It may be calculated in primary care to stratify the severity of the infection.

0 - Low risk (mortality <1%), 1-2 - intermediate risk (mortality 1-10%), 3-4 - high risk (mortality >10%).

Clinical judgement must be used to determine who needs hospital assessment (+/- admission), however, the CRB-65 can be used to help guide this decision. Patients should be considered for home-based care if they score 0, whilst hospital assessment should be considered for all other patients (especially if ≥ 2)

CURB-65

CURB-65 is calculated when a patient presents to hospital, it includes a urea measurement and helps establish the best place of care.

0-1 - Low risk (mortality <3%), 2 - intermediate risk (mortality 3-15%), 3-5 - high risk (mortality >15%).

As with the CRB-65 clinical judgement is key, however, as a general rule consider outpatient care for a score of 0-1, inpatient care for a score of 2 and ICU care for a score of 3 or more.

Management

Management is dependent on severity, type of infecting organism, & local hospital guidelines. Below we discuss options for empirical antibiotic treatment, this may vary depending on local guidelines.

General measures

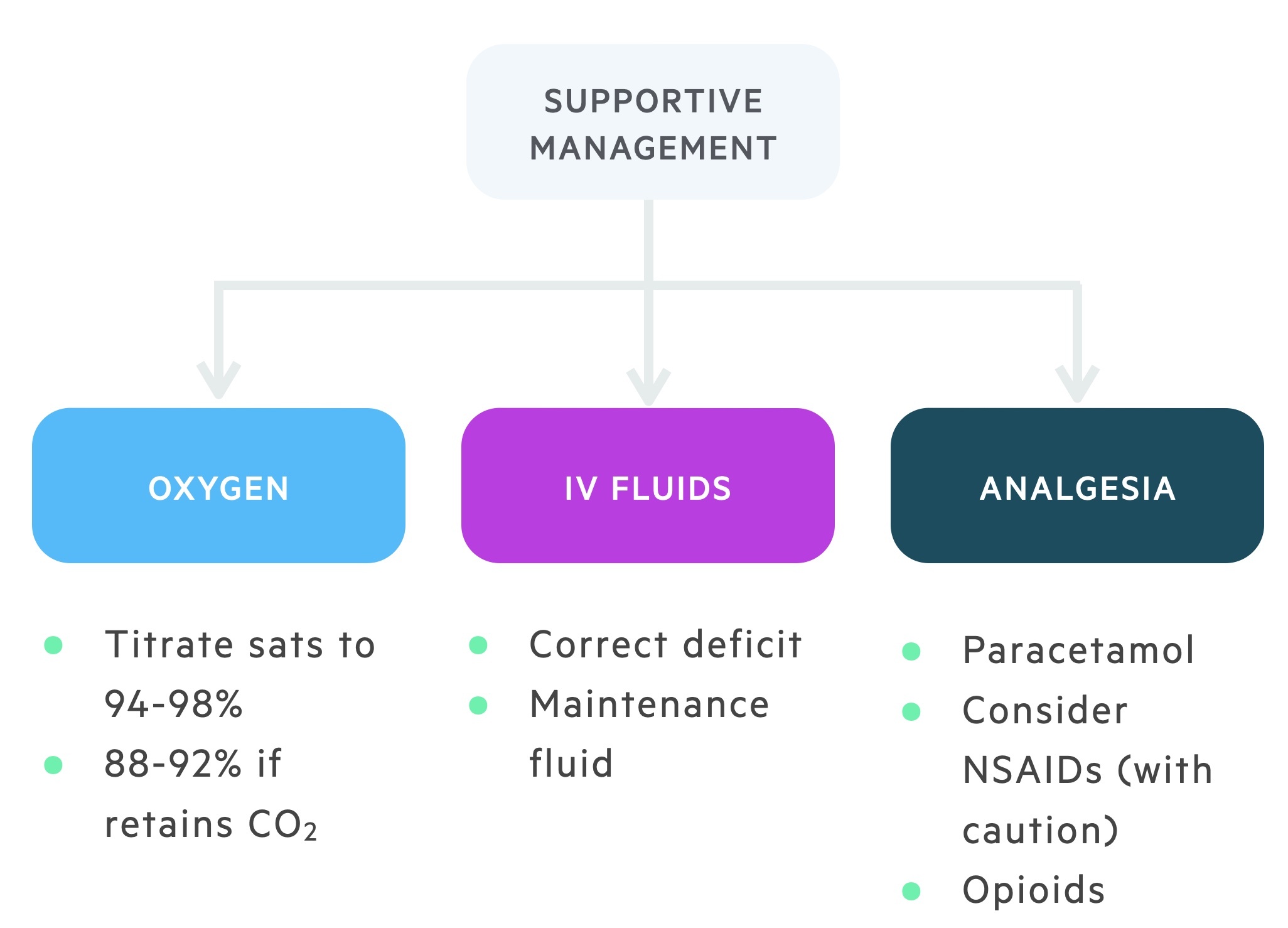

Patients may present with pneumonia of varying degrees of severity. In those who are acutely unwell physicians should adopt an ABC approach. A number of general measures should be considered in the treatment of a patient hospitalised with pneumonia.

- Oxygen titrated to saturations: Aim for saturation of 94-98% in patients without underlying lung disease. In patients at risk of type II respiratory failure (e.g. COPD) aim for saturations of 88-92%.

- IV fluids: patients may be dehydrated, correct any deficit and prescribe maintenance fluids as appropriate.

- Appropriate analgesia: Paracetamol may be sufficient. NSAIDs may be used with appropriate consideration and care. In cases of more severe pain consider opiate analgesics. Care should be taken due to respiratory depressant effects.

Antibiotics

Treatment should follow local antibiotic guidelines with input from microbiology as required. For those seeking detailed guidance, NICE have guidelines covering management of both CAPs and HAPs:

- NG 138: Pneumonia (community- acquired): antimicrobial prescribing (published 2019)

- NG 139: Pneumonia (hospital-acquired): antimicrobial prescribing (published 2019)

Community-acquired:

Low severity:

- Oral therapy with a broad spectrum beta-lactam (e.g. amoxicillin).

- A tetracycline or macrolide may be used in those with a penicillin allergy (doxycycline or clarithromycin).

- A typical antibiotic course would be 5-7 days.

Intermediate severity:

- Most can be treated adequately with oral therapy.

- Dual therapy with a beta-lactam (e.g. amoxicillin) and a macrolide (e.g. clarithromycin).

- Doxycycline may be used as an alternative in those with a penicillin allergy.

- A typical antibiotic course would be 7-10 days.

High severity:

- IV beta-lactamase stable beta-lactam (e.g co-amoxiclav) and a macrolide (e.g. clarithromycin).

- An antibiotic course of 7-10 days may be extended to 14 or 21 days depending on clinical circumstance.

Hospital-acquired:

- Should follow local guidelines based upon local microbial knowledge.

- Co-amoxiclav 625mg orally TDS may be used in mild infections.

- Tazocin (piperacillin/tazobactam) 4.5g IV TDS may be used in severe infections.

Follow-up CXR

Research indicates that 11% of smokers over the age of 50 who have pneumonia have lung cancer. This may be incidental or causative, tumours may block parts of the bronchial tree increasing the risk of infective events.

A CXR at 6-8 weeks post-event should be used to screen for underlying lung cancers in this age group.

Last updated: December 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback