Amyloidosis

Notes

Overview

Amyloidosis refers to the extracellular deposition of fibrils that contain a variety of proteins.

An amyloid fibril is simply the assembly of insoluble protein fibres that are composed in a way that is resistant to degradation. This composition is known as a beta-pleated sheet. These deposits of amyloid fibrils are extracellular (i.e. occurring outside of cells) and may be seen in different tissues and organs.

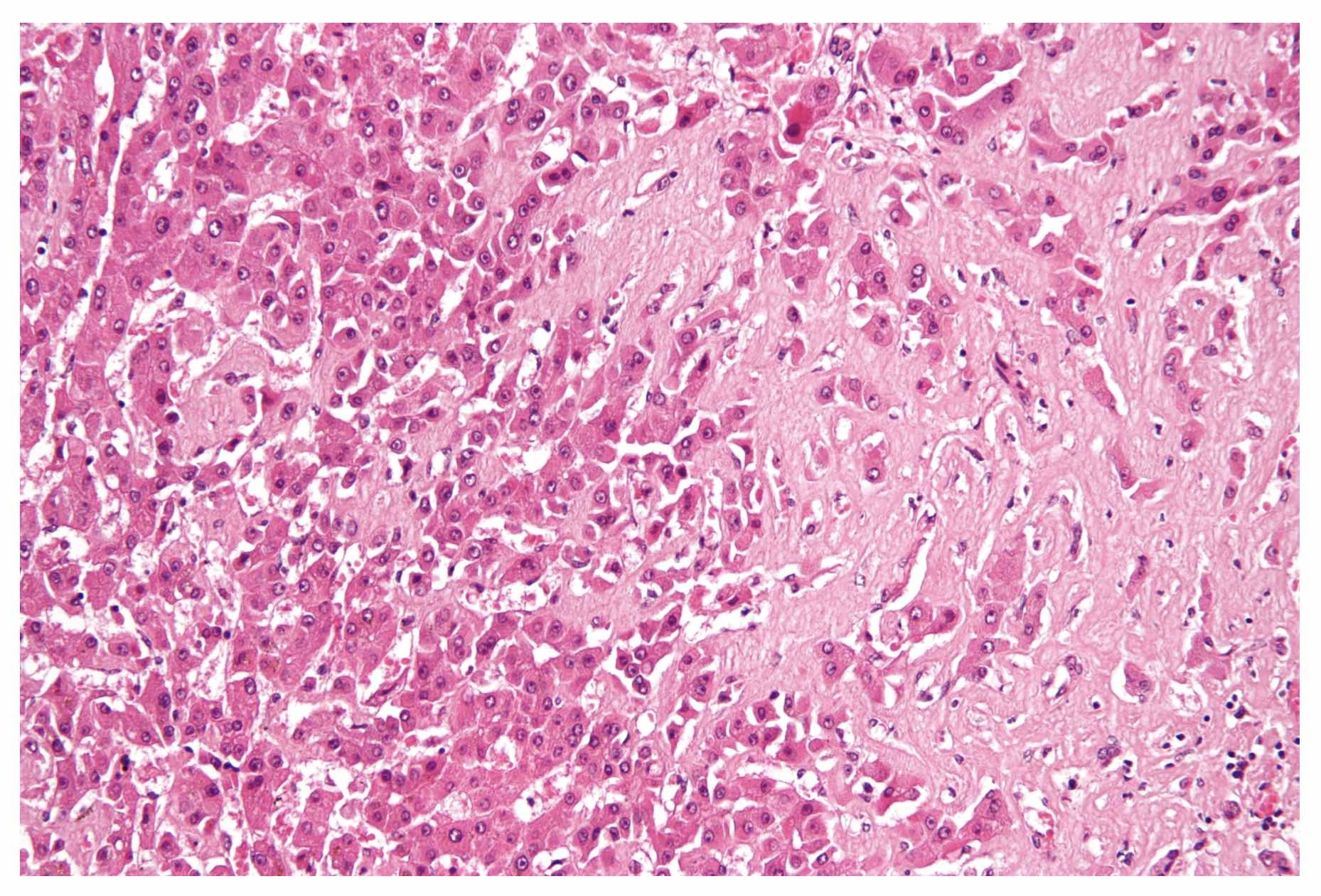

Hepatic amyloid. Seen as amorphous, acellular pink material on H&E stain

Image courtesy of Nephron. Wikimedia commons

The problem with amyloid is that deposition in tissue can lead to organ dysfunction. When organ dysfunction is caused by amyloid we usually refer to it as amyloidosis. Amyloidosis may be systemic or localised:

- Systemic: widespread deposition of amyloid that can affect multiple organs

- Localised: amyloid deposits at the site of production so only one organ is affected

Amyloid may be classified according to the specific precursor protein. For example, AA amyloidosis is due to the precursor serum amyloid A (SAA) protein and AL amyloidosis is due to the precursor immunoglobulin light chain.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

Amyloid fibrils are derived from soluble proteins that undergo conformational/structural changes.

Amyloid fibrils can contain a variety of insoluble proteins. They are derived from soluble proteins (e.g. immunoglobulin light chains, amyloid precursors) that range in size from 5-25 kDa and subsequently undergo conformational/structural changes due to a variety of reasons. They subsequently form a beta-pleated sheet configuration that is resistant to degradation. Deposition in organs leads to disruption of normal tissue function and the development of organ failure.

There are at least 38 human precursors to amyloid fibrils. Examples include:

- AL amyloid: derived from immunoglobulin light chain fragments

- ATTR amyloid: derived from the protein transthyretin

- AA amyloidosis: derived from serum amyloid protein A

These amyloid fibrils and the associated precursor proteins can be associated with an underlying disease process that may be inherited or acquired. Examples include:

- Alzheimer’s disease: due to abnormal conformation of the amyloid precursor protein

- Familial amyloid polyneuropathy I: due to variants in the protein transthyretin

- Secondary systemic amyloidosis: due to high-level production of serum amyloid A protein

Hereditary (i.e. inherited) forms of amyloidosis are due to genetic mutations in genes that encode the precursor proteins. In acquired forms, there is usually an excess formation of precursor proteins. For example, in AL amyloidosis there are excess light chain fragments produced by plasma cell malignancies, and in AA amyloidosis there is excess serum amyloid A protein from chronic inflammatory disorders.

Ultimately, the build-up of amyloid in organs disrupts normal cellular function and can lead to organ failure. In certain hereditary forms of amyloidosis, for example, patients may develop progressive heart failure, peripheral neuropathy, and autonomic dysfunction amongst other pathologies.

Clinical features

The features of amyloidosis depends on the organ(s) affected.

Different forms of amyloid may affect different organs within the body. As deposition or local production of amyloid continues there is progressive organ dysfunction and eventually failure. The severity largely depends on the amount of amyloid deposited.

Heart

Cardiac involvement is characterised by the development of heart failure. This is usually diastolic initially (i.e. abnormal relaxation) that progresses to systolic failure over time. Patients are also at risk of dangerous arrhythmias and heart block due to the involvement of the electrical system.

Typical features

- Heart failure: shortness of breath, orthopnoea, oedema

- Arrhythmias: palpitations

- Heart block: syncope, collapse

Lungs

Pulmonary involvement may present in several different ways depending on the location of the deposition. Upper airway involvement can lead to obstructive symptoms with hoarseness and stridor. Lower airway involvement can cause persistent pleural effusions.

Typical features

- Pleural effusions: shortness of breath, dull percussion, reduced breath sounds

- Tracheobronchial infiltration: features of airway obstruction

Kidneys

Renal involvement is characterised by asymptomatic proteinuria. Significant deposition may cause nephrotic syndrome and progressive renal dysfunction.

Typical features

- Proteinuria: frothy urine

- Nephrotic syndrome: proteinuria, hypoalbuminaemia, oedema

- Chronic kidney disease: fatigue, lethargy, hypertension, oliguria

Liver

Amyloid deposition in the liver typically leads to hepatomegaly and elevated alkaline phosphate (ALP). Isolated rises in ALP are suggestive of liver infiltration. Chronic liver disease is rare.

Typical features

- Hepatomegaly

Gastrointestinal

Involvement of the GI tract can lead to a range of clinical features depending on the extent and location of involvement.

Typical features

- Bleeding: often due to mucosal lesions, vascular friability or ischaemia

- Malabsorption: a variety of mechanisms, that ultimately leads to weight loss, nutrient and vitamin deficiency

- Dysmotility: commonly causes slow transit leading to nausea, vomiting, constipation

Nerves

The central or peripheral nervous systems may be affected by amyloid

Typical features

- Peripheral neuropathy: a mixture of sensory and motor

- Autonomic neuropathy: for example, abnormal blood pressure control

- Cerebral bleeding: due to amyloid angiopathy

- Dementia

Other

Many other organ systems may be affected by amyloid. Some of these include:

- Eyes: commonly cause dryness

- Haematological: can cause bleeding due to abnormal activity of factor X

- Musculoskeletal: wide variation. Classically causes arthropathy, macroglossia (large tongue), or even carpal tunnel syndrome

Diagnosis & investigations

The definitive diagnosis of amyloid is made on tissue biopsy.

It may be very difficult to diagnose amyloid and in the early stages of the disease, it requires a high degree of suspicion. Features that may suggest underlying amyloid include:

- Unexplained proteinuria / nephrotic syndrome

- Cardiac failure

- Progressive peripheral neuropathy

- Unexplained hepatosplenomegaly

- Presence of known precipitating condition (e.g. multiple myeloma, chronic inflammatory disease, family history)

When amyloid is suspected diagnosis is based on a tissue biopsy. This does not need to be from the suspected site of organ dysfunction but from a site of known amyloid deposition such as subcutaneous fat, minor salivary glands, or rectal mucosa. In some cases, a biopsy from the dysfunctional organ may be needed (e.g. kidneys). The abdominal fat pad biopsy is commonly chosen first.

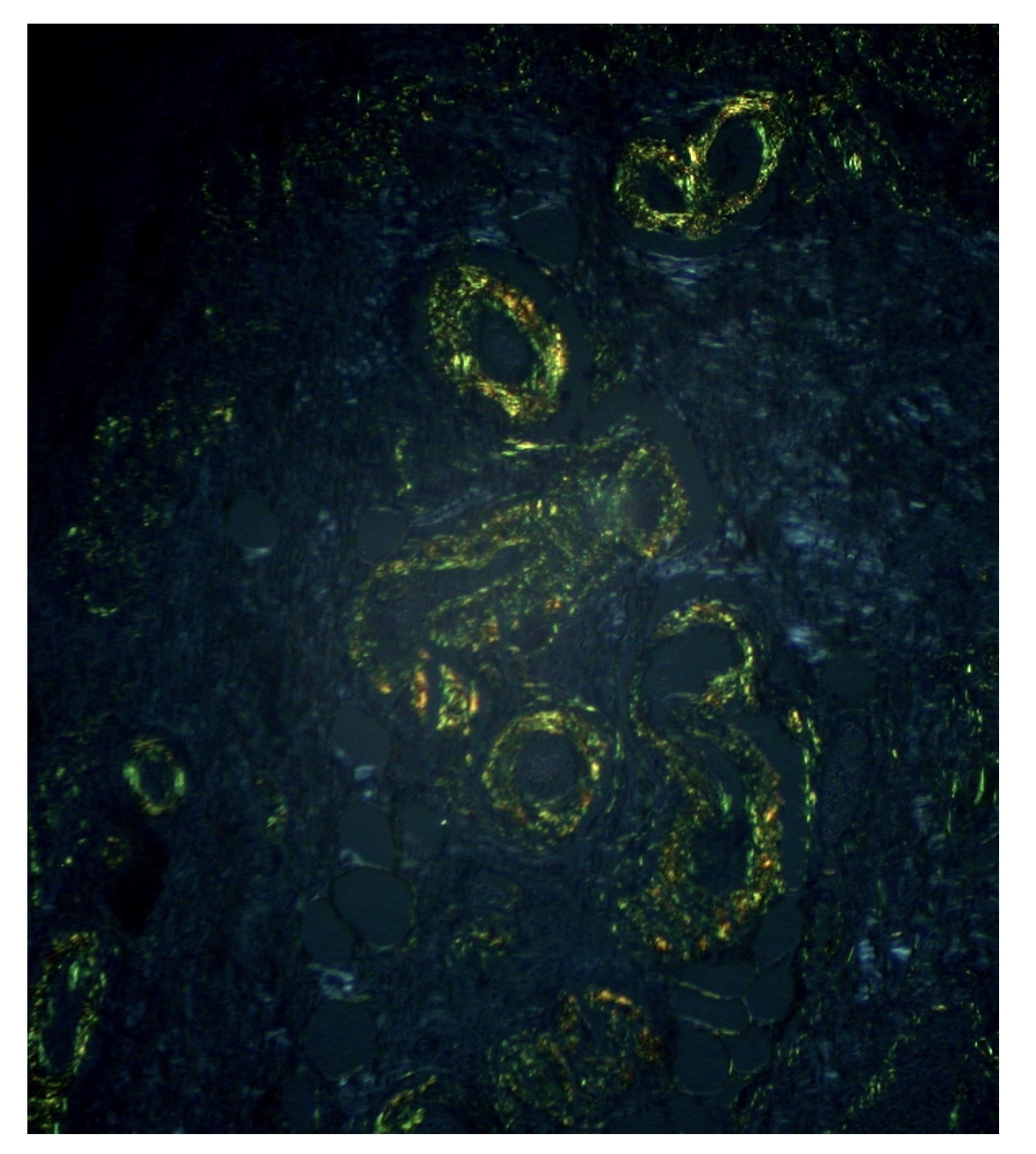

A biopsy is important because it enables the identification of amyloid under the microscope. Amyloid fibrils are identified using Congo red staining, which leads to apple-green birefringence under polarised light. A variety of other laboratory techniques may be used to identify the type of amyloid including immunohistochemistry, amino acid sequencing, or mass spectroscopy.

A variety of other investigations may be utilised to look for the extent of amyloid and organ involvement (e.g. computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, echocardiography).

Gastric amyloid treated with Congo red shows an apple-green birefringence

Image courtesy of Ed Uthman. Flickr

Management

The treatment of amyloidosis depends on the underlying cause.

There are many different types of amyloidosis and treatment largely depends on the subtype, extent of organ dysfunction, and co-morbidities of the patient. In patients with systemic amyloid, treatment is typically directed towards the underlying cause (e.g. plasma cell abnormality in AL amyloid or chronic inflammatory disorder in AA amyloid).

Various novel treatments for the clearance of amyloid from organ tissue are being explored in clinical trials. Management of the complications of the underlying organ dysfunction is critical and this usually involves input from a wide range of specialties including cardiologists, neurologists, nephrologists, and rheumatologists amongst others.

Last updated: July 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback