Ankylosing spondylitis

Notes

Overview

Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic, multi-system inflammatory disorder characterised inflammation of the sacroiliac joints and axial skeleton.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is considered a chronic, multi-system inflammatory disorder that is characterised by chronic lower back pain.

AS is one of the spondyloarthropathies (SpA) that refers to a diverse group of conditions associated with the HLA-B27 gene. The condition causes inflammation of the sacroiliac joints and axial skeleton that presents as chronic back pain, morning stiffness, and eventually spinal deformity in long-standing cases.

Spondyloarthropathies

AS is one of the SpAs that are a diverse group of conditions associated with the HLA-B27 gene.

AS is one of the SpAs that are a diverse group of conditions characterised by chronic inflammation leading to pain, stiffness, and loss of mobility. They are often referred to as the ‘seronegative spondyloarthropathies' and include:

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Psoriatic arthritis

- Reactive arthritis (Reiter’s syndrome)

- IBD-associated spondyloarthropathy

NOTE: the ‘seronegative’ label refers to both the lack of rheumatoid factor positivity and the absence of specific antibodies for each disease.

The SpAs are associated with a multitude of musculoskeletal clinical features including:

- Spinal and sacroiliac joint inflammation

- Peripheral arthritis

- Dactylitis: inflammation of an entire digit

- Enthesitis: inflammation at a tendon insertion point

- Extra-articular manifestations: uveitis, psoriasis, bowel symptoms, cardio-pulmonary disease

Due to the predominant axial skeletal involvement, they may also be collectively termed ‘axial spondyloarthropathy’ (AxSpA).

Nomenclature

The terminology relating to AS helps to conceptualise all of the SpAs.

The term ‘ankylosing spondylitis' can be broken down into two components:

- Ankylosis: this term means to fuse or stiffen, which is the key feature of this disease

- Spondylosis: means vertebral or spinal

Therefore, AS is characterised by progressive inflammation and stiffening of the spine. AS is often considered the original form of SpA. It is the first to be described and is by far the most heavily studied subtype of all SpAs.

AS, like all SpAs, may be sub-classified according to the location of the main symptom burden:

- AxSpA: predominant axial involvement (spine & sacroiliac joints)

- PSpA: predominantly peripheral joint involvement

AS may also be divided according to imaging findings:

- R-AxSpA: radiographic features present

- NR-AxSpA: no radiological evidence on x-ray. Diagnosis based on clinical assessment and/or MRI

Epidemiology

Traditionally, AS is more common in men with a 2-3:1 male-to-female ratio.

The prevalence of AS varies depending on the population. It ranges from 0.7-49 per 10,000 population across a number of countries. In the UK, the prevalence is estimated at 0.05-0.23%.

The classic male to female ratio is 3:1, however, this estimate is decreasing with the advent of MRI. Non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (i.e. not identified on conventional x-ray) is seen to affect men and women equally. The age of onset in AS is usually 20-30 years old and up to 95% of patients will present before 45 years old.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

The cause of AS is not yet fully clear, but it is known to have a strong genetic element.

The exact cause of AS is unknown, but there is suspected to be a strong genetic element with the involvement of the HLA-B27 gene. The development of AS (and other SpAs) is suspected to be a complex interaction between an individual's genetic make-up, gut microbiome (i.e. population of bacteria living in the gut), immune response, and mechanical stress at typical anatomical sites (e.g. axial skeleton).

The strongest genetic contribution is linked to HLA-B27, which is one of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) Class I molecules.

Genetic factors

MHC are a group of genes that encode proteins found on the surface of cells that help the immune system recognise foreign antigens. In humans, these are referred to as ‘human leucocyte antigens’ (HLA). They are differentiated into two groups:

- MHC class I (HLA-A, B, C): expressed on all nucleated cells. Important in the recognition of ‘self-antigens’. Further divided into multiple subtypes.

- MHC class II (HLA-DR, DQ, DP): expressed on antigen-presenting cells (e.g. T-helper cells, dendritic cells). Important for activation of the adaptive immune response. Further divided into multiple subtypes.

The MHC class I subtypes are partly responsible for regulating the adaptive immune system and present intracellular peptides to MHC Class I receptors on a range of cells, such as CD8+ T cells, natural killer cells, and monocytes. This allows inflammation to occur in tissues without an external stimulus that typically occurs in association with HLA-B27. The allele HLA-B27 is particularly common in Caucasians (5-6% prevalence). Other factors must be important in the development of AS because only 1-5% of patients with HLA-B27 develop AS.

Other genetic factors have been implicated in AS including several non-HLA genes (e.g. interleukin 23 receptor variants). AS is more common in patients with a family history of AS or other SpAs.

Environmental factors

Environmental factors are also implicated to a modest degree and general advice on exercise and smoking cessation is vital in the overall disease course, with smokers noted to have much higher rates of pain and disability overall and exercise therapy being a cornerstone of management regardless of disease activity.

Disease activity

The disease usually presents with early sacroiliac joint involvement leading to inflammatory back pain. This is followed by the involvement of the spine. In the spine, there is initial inflammation at the junction between the vertebrae and intervertebral discs. The outer fibrous layer of the disc (known as the annulus fibrosis) undergoes ossification (i.e. turns into bone) and forms syndesmophytes (i.e. ossification of a spinal ligament or annulus fibrosis).

Syndesmophytes may bridge together across multiple vertebrae leading to the classic ‘bamboo spine’ that significantly reduces spinal mobility.

Clinical features

Chronic lower back pain and morning stiffness are characteristic of AS.

Clinical features usually start insidiously at a young age (< 45 years). Back pain characteristically occurs at night, improves with exercise, and does not get better with rest.

- Back pain (worse with inactivity, improves with exercise): sacroiliac and spinal involvement

- Neck pain

- Alternating buttock pain

- Morning stiffness

- Fatigue

- Arthritis

- Enthesitis (inflammation at the insertion of tendons and ligaments)

- Positive Schöber test (assesses decrease in lumbar spine flexion)

- Spinal deformity (seen in advanced disease)

- Extra-articular manifestations (see below)

Peripheral musculoskeletal sites commonly involved in AS include the Achilles tendon, plantar fascia, base of the fifth metatarsal, tibial tuberosity, patella, and iliac crest amongst others.

Schöber test

The L5 spinous process is identified and marked with the patient standing up. Typically lies at the level of the sacral dimples. Another mark is made 10 cm above this first line. The patient is then asked to bend forward in an attempt to touch their toes. The distance between the two lines is remeasured with the patient fully flexed. An increase of < 5 cm during flexion is considered a positive test.

The modified Schöber test is very similar but involves identification of the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). A line is then drawn 10 cm above the PSIS and 5 cm below the PSIS. The distance between the top and bottom line is then measured during full forward flexion and interpreted in the same way.

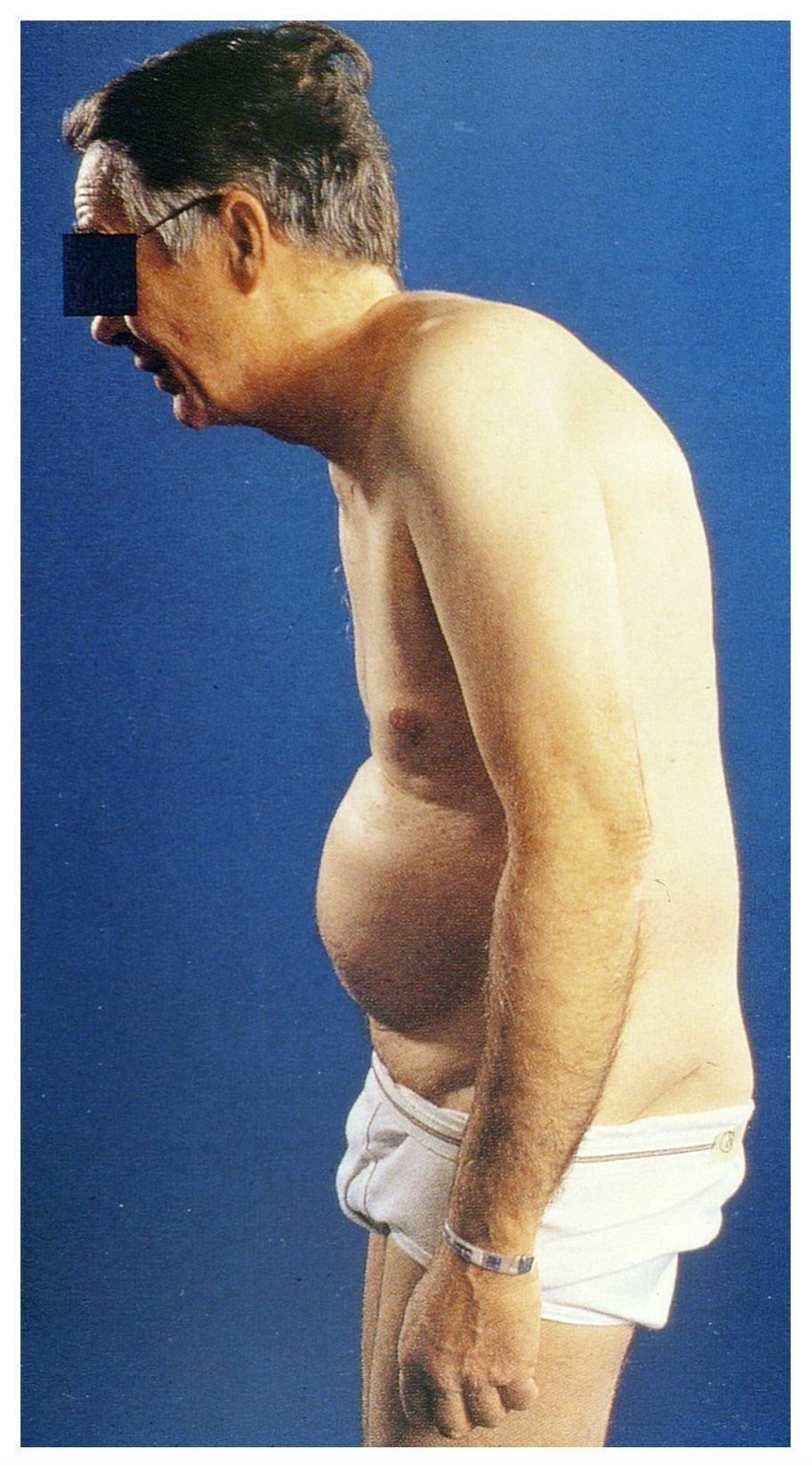

Spinal deformity

As the disease progresses, fixed spinal deformities may develop leading to reduced mobility and functional impairment. A ‘hunched back’ is common due to hyperkyphosis of the thoracic vertebrae. In more advanced disease the characteristic ‘question mark’ posture may develop due to a combination of thoracic hyperkyphosis, loss of lumbar lordosis, and flexion deformities of hips and neck.

Typical 'question mark' posture of long-standing AS

Image courtesy of Mehlauge. Wikimedia Commons.

Extra-articular manifestations

Several extra-articular features may be seen in AS that refer to systemic clinical manifestations.

The extra-articular manifestations of AS may be remembered as the seven ‘A’s’:

- Aortitis: can lead to aortic regurgitation

- Anterior uveitis: inflammation of the middle layer of the eye (i.e. the uvea). Typically causes unilateral eye pain, redness, and photophobia. Seen in 25-35% of individuals with SpA

- Atrioventricular block

- Atlanto-axial instability: increases risk of cord compression

- Apical lung fibrosis

- Amyloidosis: secondary to chronic inflammation

- IgA nephropathy

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of AS is based on the presence of typical clinical and radiological features.

Patients with AS (or SpA with axial involvement) are commonly misdiagnosed as mechanical lower back pain. Therefore, clinicians should have a low index of suspicion in young patients presenting with inflammatory back pain.

When to suspect?

A patient under 45 years old with a 3 months history of lower back pain should be referred to a rheumatologist for assessment of SpA if ≥4 of the following criteria are met:

- Onset < 35 years old

- Waking during second half of night (due to symptoms)

- Buttock pain

- Improves with exercise

- Improves with NSAIDs (within 48 hours)

- First-degree relative with SpA

- Current/past arthritis

- Current/pas enthesitis

- Current/past psoriasis

NOTE: if only 3 criteria are present then testing for HLA-B27 can be considered.

In addition, patients who develop peripheral symptoms of SpA (e.g. dactylitis, enthesitis in the absence of a mechanical cause) or extra-articular manifestations (e.g. anterior uveitis) should be considered for urgent referral to a rheumatologist.

Diagnostic criteria

Various criteria have been developed to aid the diagnosis of all SpAs. Some of these are generalised to all SpAs (e.g. European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group) whereas others are specific to a condition (e.g. Classification of Psoriatic Arthritis).

One of the most commonly used criteria to aid the diagnosis of AS is the 1984 Modified New York Criteria (validated in AS but now used in all SpA with axial involvement):

Clinical criteria

- Low back pain ≥ 3 months, improved by exercise and not relieved by rest

- Limitation of the lumbar spine in sagittal and frontal planes

- Limitation of chest expansion (relative to normal values corrected for age and sex)

Radiological criterion

- Bilateral grade 2-4 sacroiliitis OR unilateral grade 3-4 sacroiliitis

Diagnosis

- Definite ankylosing spondylitis: radiological criterion is present plus at least 1 clinical criterion

- Probable ankylosing spondylitis: if EITHER radiological criterion OR 3 clinical criteria are present alone

Another commonly used diagnostic criteria is the ASAS criteria for axial SpA.

Investigations

Imaging in AS is important to assess for the presence of inflammatory joint disease.

Imaging (e.g. pelvic & spinal x-rays) is crucial to look for typical changes of AS and usually the first-line investigation in patients with inflammatory back pain. Various algorithms exist (e.g. Berlin algorithm) to help diagnose AS or AxSpA (i.e. a SpA with axial involvement) in patients with suspected inflammatory back pain.

Bloods

Inflammatory markers may be requested to aid the diagnosis (e.g. CRP/ESR), but can be normal and are non-specific. Routine blood tests are usually requested to look for complications and ensure it is safe to provide treatment (e.g. renal function and haemoglobin prior to long-term NSAID use).

Testing for HLA-B27 is useful, but a negative test does not exclude the diagnosis. The majority of people with the HLA-B27 gene will not have AS, but a significant proportion of AS have the gene. Usually requested if sacroiliitis is not identified on x-ray imaging.

X-rays

Spinal/pelvic x-rays are usually the first-line imaging in suspected inflammatory back pain. However, they may be normal in early disease and women are more likely to have disease not seen on x-ray. Sacroiliitis may be graded according to x-ray findings:

- Grade 0 (normal)

- Grade I (suspicious): blurring of joint margins

- Grade II (minimal): localised erosion/sclerosis. No change to joint width

- Grade III (abnormal): advanced erosions with evidence of sclerosis/widening/narrowing/partial ankylosis

- Grade IV (severe): complete ankylosis

The grade and laterality (i.e. unilateral or bilateral) of sacroiliitis on x-ray is used in the diagnostic criteria for AS. In the absence of x-ray findings, patients with suspected inflammatory back pain may be tested for HLA-B27 and undergo more detailed imaging with MRI.

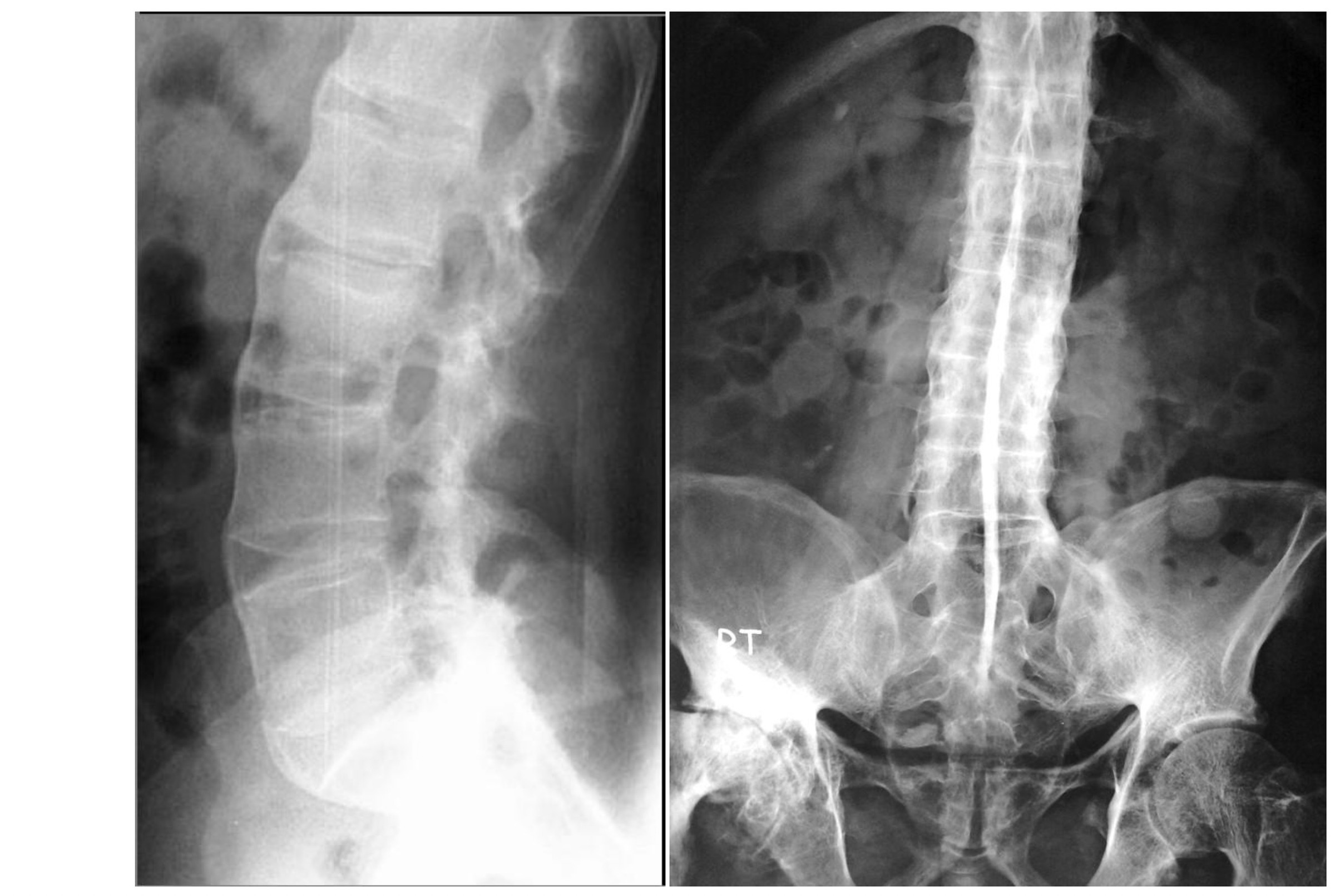

Pathognomonic features of AS may occur in advanced disease that includes:

- Dagger sign: ossification of the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments leading to a central radiodense line running up the spine.

- Bamboo spine: vertebral body fusion by marginal syndesmophytes and squaring of the vertebral bodies. Gives the impression of a continuous lateral spinal border on x-rays like a bamboo stem.

Bamboo spine (left) and Dagger sign (right) on spinal x-rays

Image courtesy of Radswiki (left) and Dr Wael Nemattalla (right). Radiopaedia. Creative Commons license

MRI

An unenhanced MRI may be requested in patients with suspected inflammatory back pain with normal x-rays. Specific sequences are requested and images should be interpreted according to specific MRI criteria (e.g. ASAS/OMERACT).

If imaging is non-diagnostic, the diagnosis could be made based on clinical features and the presence of HLA-B27. Alternatively, a follow-up MRI can be requested.

Other investigations

Further investigations depend on the pattern of musculoskeletal involvement. For example, peripheral joint x-rays, musculoskeletal ultrasound, and/or MRI may be needed for peripheral arthritis or enthesitis.

Scoring systems

A variety of scoring systems can be used to monitor symptoms and functional ability of patients with AS.

The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Activity Index (BASDAI) is a commonly used scoring system in AS that helps to evaluate disease activity and ultimately can be used to assess response to treatment. The BASDAI is a six-part questionnaire where each question is scored 1-10. It is a subjective assessment of severity.

Other scoring systems that can be used in AS include:

- Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS)

- Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI): assess spinal mobility

- Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI): assess functional status

These scores may be applied to all subtypes of SpA with axial involvement (i.e. AxSpA).

Management

The goal of treatment in AS is to relieve symptoms, maintain functional independence and prevent disease progression.

The management of AS depends on the severity of presentation, the pattern of involvement (e.g. peripheral involvement), and presence of co-morbidities (e.g. any contraindications to treatment).

The principal management is the use of non-pharmacological treatments (e.g. physiotherapy) and NSAIDs. In patients with severe disease or non-response to initial therapy then biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) can be given (e.g. Anti-TNF agents). The NICE clinical guideline 65 gives a general overview of recommendations for the treatment of all SpAs.

Non-pharmacological management

A range of non-pharmacological management strategies should be employed for patients with AS.

- Patient education

- Smoking cessation

- Psychological support

- Physiotherapy: exercise has been shown to improve disease activity in AS

Patients with AS should be referred to a specialist physiotherapist to assist in a structured exercise programme. Depending on the pattern of disease involvement more specialist therapists (e.g. hand therapist) may be needed.

NSAIDs

The use of NSAIDs (e.g. naproxen, ibuprofen, or more selective COX-2 inhibitors like celecoxib) should be offered to all patients with symptomatic AS if there are no major contraindications. They may be prescribed alongside proton pump inhibitors to protect the gastric mucosa. NSAIDs can also be used to treat peripheral arthritis symptoms.

NSAIDs may be the only medication required to treat AS in a significant number of patients with major relief of symptoms. Following a trial of NSAID therapy, symptoms should improve in 2-4 weeks. Some patients need to continue NSAIDs daily whereas others may adopt a more ‘on demand’ administration according to symptoms. It is critical to consider long-term gastric, renal, and cardiac side-effects when prescribing long-term NSAIDs.

DMARDs

DMARDs refer to a broad range of medications that involve suppression of the immune system to treat a variety of immune-mediated diseases, particularly in rheumatology. There are broadly divided into two categories:

- Conventional DMARDs: Various drugs with different mechanisms (e.g. Methotrexate, Leflunomide, Sulfasalazine)

- Biological DMARDs: monoclonal antibodies that fall into different classes (e.g. Anti-TNF)

Conventional DMARDs are generally ineffective in patients with axial involvement and therefore not commonly used in patients with AS or other SpAs with axial involvement. They are effective for patients with peripheral involvement and therefore more commonly seen in patients with psoriatic arthritis or reactive arthritis.

Biological DMARDs are the principal treatment for patients with AS not responsive to NSAIDs and non-pharmacological treatments. Anti-TNF agents are the first-line biological DMARDs in patients with severe active AS who cannot tolerate or have not adequately responded to, NSAIDs. Examples include infliximab, golimumab, or adalimumab. Response to treatment is assessed by the BASDAI and/or spinal pain visual analogue scale.

Patients who fail to respond to one anti-TNF agent may be tried with a different anti-TNF agent. Another option is secukinumab (IL-17A inhibitor) but other treatments can only be given as part of a clinical trial (e.g. Janus kinase inhibitors).

Complications

AS has a variable course, but can lead to irreversible disease with chronic functional limitations.

The prognosis of AS depends on the age of presentation, extra-articular involvement, and response to treatment. It can have a significant impact on morbidity due to progressive spinal disease and functional limitations. AS is associated with a decreased quality of life and work productivity.

Complications associated with AS can include:

- Spinal fusion: limits mobility

- Spinal fractures: higher risk as the disease progresses (up to 10%)

- Osteoporosis: up to one third

- Restrictive lung disease: due to apical fibrosis and thoracic cage abnormalities

- Spinal cord injury: due to fractures or stenosis

- Cardiac disease: valvular disease, heart failure, arrhythmias

Last updated: May 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback