Systemic sclerosis

Notes

Overview

Systemic sclerosis is a chronic, multi-system disorder that is characterised by widespread vascular dysfunction and fibrosis.

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a chronic multi-system disorder. The condition is heterogeneous and can present with a range of clinical manifestations involving multiple organs. One of the hallmark features of SSc is thickened, hardened skin known as scleroderma. The term scleroderma is often used synonymously with SSc.

Disease subtypes

SSc may be divided into several disease subtypes based on the extent of skin involvement and pattern of organs affected.

- Limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (lcSSc): characterised by sclerosis (hardening) of the skin in the distal limbs. Some involvement of face and neck seen. May develop systemic features (e.g. oesophageal dysmotility, pulmonary hypertension). May manifest the CREST syndrome (see below)

- Diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (dcSSc): characterised by extensive sclerosis of the skin. May be difficult to distinguish from limited form, but considered diffuse if proximal limbs and/or trunk involvement. More likely to have rapid disease progression and internal organ involvement.

- Systemic sclerosis without scleroderma: presence of typical systemic features and serological markers of SSc in the absence of skin lesions.

Overlap syndromes

Patients with SSc may develop clinical features that overlap with other systemic rheumatological conditions including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or Sjögren's syndrome (SS).

Any disease subtype of SSc may present with an overlap syndrome.

Epidemiology

The majority of patients with SSc are female.

The incidence and prevalence of SSc varies by geographical regions and different populations. In the UK, the prevalence has previously been reported as 88-443 per million people.

Overall, SSc has a female predominance (estimated 3-6:1 female to male ratio). However, women tend to present at a younger age with lcSSc, whereas men tend to present with dcSSc and more severe systemic disease (e.g. interstitial lung disease). The majority of patients develop SSc between 20-60 years old.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

The exact cause of SSc remains unknown.

SSc is characterised by immune-mediated damage to vascular structures (e.g. blood vessels) and excessive synthesis and deposition of extracellular matrix structures (e.g collagen). This leads to chronic fibrosis, scarring and damage to organs.

The predominant organs involved include:

- Skin

- Lungs

- Heart

- Gastrointestinal tract

- Kidneys

- Musculoskeletal system

- Nervous system

Triggering event

A series of environmental triggers have been postulated (e.g. silica exposure), but it is unclear exactly what drives the interplay between immune system, vasculature and fibrosis (induced by fibroblasts that produce collagen when activated).

Vascular changes

Vascular changes are observed in SSc with alteration to chemical mediators involved in vascular tone (i.e. resistance to flow). These mediators include Endothelins and nitric oxide (NO). Endothelin-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor and fibrogenic with elevated levels identified in SSc. NO is a vasodilator and opposes the action of Endothelins. The balance between NO and Endothelin is thought to be disrupted in SSc.

Immune activation

Vascular damage leads to activation of endothelial cells, release of adhesion molecules and increased leucocyte migration into peripheral tissue. This leads to release of profibrotic cytokines, including transforming growth factor beta, interleukin 4 and platelet-derived growth factor among others. These activate fibroblasts and lead to collagen deposition and fibrosis. This immune activation and release of profibrotic cytokines is central to the pathogenesis of SSc and why immune-mediated therapies are utilised.

Autoantibodies

An estimated 95% of patients with SSc have autoantibodies to nuclear antigens. There is thought to be a loss of immune tolerance with the body reacting to self-antigens due to cross-reactivity or abnormal packaging of epitopes (part of the antigen that attaches to an antibody). How these autoantibodies are involved in the pathophysiology is not clear, but they are characteristic markers of SSc (and other rheumatology conditions) supporting the diagnosis.

Anti-nuclear antibodies

Testing for anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) screens for the presence of antibodies that are reacting to nuclear antigens. Up to 95% of patients with SSc have a positive ANA. There are different staining patterns of ANA (e.g. diffuse, speckled, nucleolar) that depend on the ENA present.

Extractable nuclear antigens

The extractable nuclear antigens (ENA) refer to the specific nuclear antigen ANA antibodies are reacting to. ENA panels are usually added by the laboratory following a positive ANA. The expression of ENA is variable depending on the subtype of SSc.

- Anti-Scl-70: associated with dcSSc. Seen in 10-40%

- Anti-centromere: associated with lcSSc. Seen in 15-40%. Seen in only 5% of diffuse form.

- Anti-RNA polymerase III: seen in up to 25% of dcSSc. Associated with renal involvement and malignancy

- Anti-PM-Scl: seen in overlap syndrome between SSc and myositis (i.e. dermatomyositis/polymyositis).

- Anti-U1 RNP: associated with mixed connective disease (MCTD). Patients have features of SLE, SSc and myositis with or without SS.

Cutaneous manifestations

Skin involvement is seen in almost all patents with SSc.

Skin changes are characterised by thickening and hardening, which is known as scleroderma. The pattern of skin change correlates to whether the disease is limited (distal limbs +/- face and neck) or diffuse (proximal limbs + trunk). A range of other cutaneous manifestations may occur in SSc.

Classic changes

- Pruritus (usually early)

- ‘Puffy’ appearance due to oedema (often seen in digits)

- ‘Salt and pepper’ appearance: due to hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation

- Loss of hair

- Dryness

- Changes to capillaries in nail bed: may only be seen with special dermatoscope (Capillaroscopy)

- Atrophy of subcutaneous tissue

- Ulcerations: may be seen over joints due to tight skin or on finger tips

- Telangiectasia: abnormal dilation of capillary

- Calcinosis: calcium deposits in the skin

- Perioral skin tightening with decreased oral opening: gives rise to a ‘pursed-string’ appearance

Raynaud phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon refers to skin colour changes that occur in the fingers and toes from vasospasm. For more information see Raynaud phenomenon notes.

It is found in most patients with SSc and may predate the condition. Raynaud phenomenon is common, so it is important to distinguish those with primary Raynaud (benign condition) from secondary Raynaud (associated with underlying condition). Raynaud phenomenon in SSc is usually more severe with risk of tissue ischaemia and necrosis. Consequently, digital ulcers may be seen in up to 50%. More common in dcSSc and those anti-Scl-70 positive.

CREST syndrome

CREST syndrome refers to the characteristic clinical manifestations of limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis.

CREST refers to a mnemonic for the clinical manifestations of lcSSc. The term is often used synonymously with limited SSc. The condition is associated with anti-centromere autoantibodies.

Mnemonic

- C - calcinosis: calcium deposits in the skin

- R - Raynaud phenomenon

- E - oEsophageal dysmotility: swallowing difficulty

- S - sclerodactyly: skin thickening and hardening affecting the fingers and toes

- T - telangiectasia: dilated capillaries. Usually appear on face, palms and mucous membranes

Systemic manifestations

SSc is a multi-system disorder leading to progressive organ dysfunction due to fibrosis.

Here, we highlight some of the key systemic manifestations of SSc. This is not an exhaustive list and detailed discussion about each aspect is beyond the scope of these notes.

Cardiac

- Pericardial disease (e.g. pericarditis, effusions)

- Myocardial disease (e.g. myocarditis, systolic or diastolic dysfunction)

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Arrhythmias

Pulmonary

Involvement of the lungs is seen in up to 80% of patients with SSc. The disease may affect the vasculature of interstitium. Can lead to breathlessness on exertion and chronic cough. Over time may lead to right-sided heart failure.

- Pulmonary hypertension: commonly seen in long-standing lcSSc.

- Interstitial lung disease: more commonly seen in dcSSc. May lead to pulmonary hypertension due to fibrosis.

Renal

Kidney disease is common in dcSSc, but may not be clinically significant. Approximately 50% have mild elevations in serum creatinine +/- hypertension, but does not usually progress to end-stage renal disease.

One of the most severe complications of SSc is scleroderma renal crisis. This is seen in 10-15% of patients, but more common in dcSSc. It is discussed further below.

Gastrointestinal

GI symptoms may be observed in up to 90% of patients, although many may be asymptomatic.

- Oesophageal dysmotility: dysphagia, choking, coughing after swallowing

- Small bowel bacterial overgrowth: malabsorption, nausea, vomiting, constipation/diarrhoea, bloating

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux

- Angiodysplasia: may cause GI bleeding

Musculoskeletal

- Arthralgia +/- arthritis

- Tendinitis

- Contractures: shortening and tightening of muscles and tendons around joints. Leads to deformity and poor mobility. Commonly affects the fingers, but can affect larger joints

- Myopathy: may be seen in overlap syndromes with polymyositis or dermatomyositis.

Genitourinary

- Erectile dysfunction

- Decreased vaginal lubrication

- Dyspareunia: often due to vaginal introitus narrowing

Other

- Increased risk of venous thromboembolism

- Possible increased cancer risk (particularly lung)

Scleroderma renal crisis

Scleroderma renal crisis is the most serious renal manifestation of SSc.

Scleroderma renal crisis is a form of intrarenal arterial stenosis due to narrowing and obliteration of the vascular lumen. It is associated with the presence of the autoantibody Anti-RNA polymerase III.

It is characterised by:

- Sudden onset severe hypertension

- Acute kidney injury

- Relatively bland urinalysis (i.e. no overt proteinuria or haematuria)

Scleroderma renal crisis is considered a type of thrombotic microangiopathy, which refers to the occlusion of small vessels. It may be accompanied by haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopaenia. Other thrombotic microangiopathies include thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura (TTP) and haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS).

The principal treatment of scleroderma renal crisis is the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Without treatment, ESRD may develop within 1-2 months with high one-year mortality. Close monitoring of renal function is required with the introduction of ACE inhibitors due to the possible worsening of AKI. This is because angiotensin II is important for efferent arteriole tone and glomerular filtration.

Diagnosis

Formal diagnosis of SSc is based on the 2013 ACR/EULAR classification criteria.

In principle, any patient with evidence of bilateral skin thickening and hardening of the hands, puffy or swollen fingers, Raynaud phenomenon or digital ulceration should be assessed for SSc.

Abnormalities suggestive of SSc include:

- Raynaud phenomenon

- Digital changes: ulceration, calcinosis, ‘salt and pepper’ skin

- Telangiectasia

- Heartburn and/or dysphagia

- Acute onset hypertension and renal impairment

- Restrictive lung disease

- Serological evidence of autoimmune disease (e.g. ANA/ENA positive)

Like most multi-system disorders, due to the wide range of clinical manifestations distinct classification criteria are used to help diagnose SSc. The 2013 Classification Criteria developed by a joint committee of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) is commonly used.

ACR/EULAR diagnostic criteria

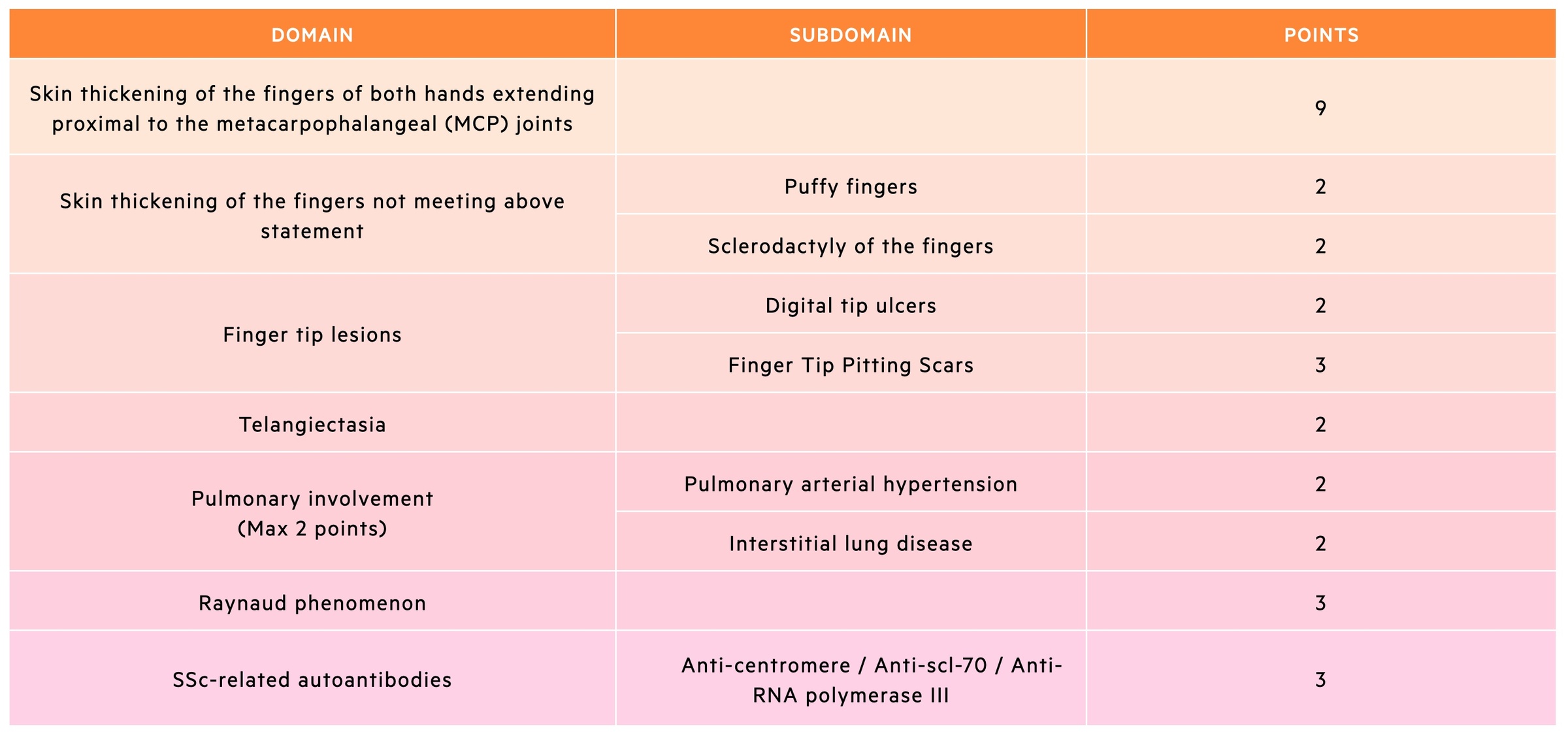

The 2013 criteria are divided into 7 items, which cover the main hallmarks of SSc. A definitive diagnosis of SSc can be made if the patient has a total score of ≥ 9.

The 2013 diagnostic criteria is useful to identify patients with definite SSc, however, it may still exclude patients who have an early diagnosis of SSc (e.g. Raynaud phenomenon with an SSc-related autoantibody).

Investigations

Investigations help determine the extent of SSc, presence of overlap syndromes and organ-specific complications.

Bedside tests

- Urinalysis: mild proteinuria or ‘bland’

- Nailfold capillaroscopy

Blood tests

- Full blood count

- ESR & CRP

- Urea & electrolytes

- Liver function tests

Autoimmune screen

This refers to a series of blood tests completed in patients presenting with a possible autoimmune disease.

- ANA

- ENA: includes SSc-associated autoantibodies (e.g. Anti-scl-70, Anti-centromere)

- Anti-CCP (if rheumatoid arthritis suspected)

- Anti-dsDNA (if SLE suspected): usually requested separately to ENAs

- Rheumatoid factor

- Complement

- Immunoglobulins

- Serum protein electrophoresis

- Creatinine kinase

- Coeliac screen

- Thyroid function tests

- Virology: hepatitis C, hepatitis B, HIV

Additional tests

These tests are important as part of the diagnostic work-up of SSc to assess for organ involvement

- Pulmonary function tests: looking for restrictive defects typical of ILD

- Chest radiograph +/- Computed tomography chest: assessment for pulmonary fibrosis

- Echocardiogram: used to screen for pulmonary hypertension

- Right heart catheterisation: in selected patients with suspected pulmonary hypertension

- Skin biopsy: in equivocal cases

Management

Prior to treatment the disease subtype of SSc must be determined.

Management of SSc depends on the underlying disease subtype and degree of organ involvement. Early referral and assessment by a rheumatologist is essential.

An in-depth management of SSc is beyond the scope of these notes. Below we outline key treatment principles in accordance with the British Society of Rheumatology guidelines.

Principles of treatment

Patients may have organ-specific treatment or systemic treatment.

- Organ-specific: treatment of specific systemic manifestations (e.g. calcium channel blockers for Raynaud phenomenon)

- Systemic treatment: use of systemic immunosuppression for patients with diffuse disease with/without severe organ involvement. Used to prevent organ failure (e.g. progressive skin disease or progressive ILD).

Systemic immunosuppression should be started early in the disease course to prevent long-term complications.

Treatment guidelines

The British Society of Rheumatology (BSR) and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology (BHPR) produced recommendations for the treatment of SSc in 2016.

This guidelines provides simply organ-specific recommendations for treatment of SSc. This divides treatment into those with limited disease, diffuse disease, overlap syndromes and organ-based complications.

- Limited (lcSSc): manage vascular complications (e.g. Raynaud phenomenon, ulceration)

- Diffuse (dcSSc): manage vascular complications and consider systemic immunosuppression. Options include Methotrexate (Dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor), Mycophenolate (Purine synthesis inhibitor), Cyclophosphamide (alkylating chemotherapy agent that crosslinks DNA and RNA) and oral corticosteroids (for severe skin disease). Autologous stem cell transplant may be used in selected cases (highly specialist therapy).

- Overlap syndrome: management should focus on the severity and activity of the overlap conditions (e.g. arthritis, SLE, myositis).

Organ-based complications

Here, we highlight key treatment options for some of the more common or more serious manifestations of SSc.

- Raynaud phenomenon: calcium channel blockers and angiotensin II receptor antagonists can be used first line.

- Severe digital ulceration: Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, endothelin receptor antagonists or intravenous prostaglandins can be used. In severe refractory cases, digital sympathectomy may be needed.

- Interstitial lung disease: depends on the extent of disease but cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate may be used

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux: proton-pump inhibitors

- Dysphagia secondary to dysmotility: prokinetics (e.g. dopamine antagonists - metoclopramide/domperidone).

- Bacterial overgrowth: intermittent broad-spectrum antibiotics

- Scleroderma renal crisis: ACE inhibitors

Prognosis

Patients with SSc have a substantial increase in mortality.

The risk of mortality in SSc is almost four-fold higher compared to age and sex-matched controls. The increased mortality is predominantly related to pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension and/or cardiac disease.

Factors associated with increased risk of death include:

- Extensive skin involvement

- Diffuse disease (dcSSc)

- Cardiac involvement

- Pulmonary involvement

- Anti-scl-70 autoantibodies

Last updated: July 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback