Jaundice

Notes

Overview

Jaundice refers to the yellow complexion that occurs from an elevated bilirubin.

Jaundice refers to the characteristic clinical finding of yellow discolouration of body tissue, particularly the skin and sclera. This occurs due to an elevation in bilirubin, which is a breakdown product of red blood cells that are taken to the liver to be modified and excreted in the bile.

Any disease process that alters the normal metabolism of bilirubin can lead to elevated levels and jaundice. This may be due to increased production or impaired excretion of bilirubin.

Clinically, jaundice is not noticeable until the bilirubin level is > 34 umol/L and it is best seen in the sclera and oral mucous membranes (e.g. under the tongue). Jaundice is an important clinical sign because it may be the first feature of liver disease or biliary obstruction that requires urgent investigation.

Bilirubin metabolism

Bilirubin is a breakdown product of heme metabolism.

Bilirubin is a breakdown product of haemoglobin, which is the oxygen-carrying pigment in red blood cells. Bilirubin is carried to the liver for processing where it can then be excreted into bile.

Formation of bilirubin

Red blood cells that contain haemoglobin are initially broken down by tissue macrophages, especially those located within the spleen. Heme is broken down by the enzyme heme oxygenase to form biliverdin, carbon monoxide and iron. Biliverdin is converted to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase.

Bilirubin then binds to albumin within the serum and is carried to the liver. Here, bilirubin is then taken up by hepatocytes for processing.

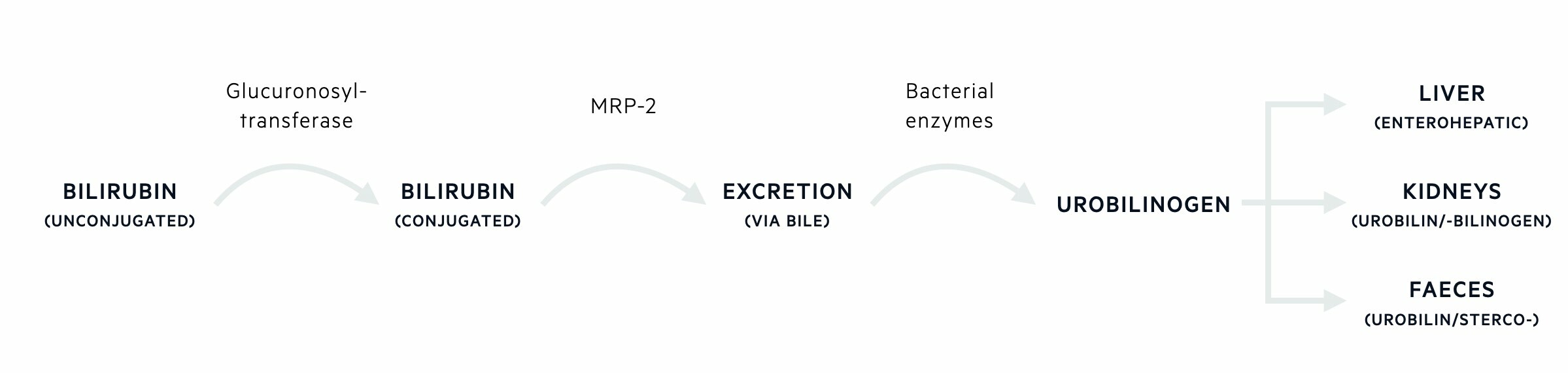

Bilirubin processing

In the liver, bilirubin needs to undergo conjugation (i.e. addition of an extra molecule) to make it more water-soluble to allow it to be excreted into bile. This process of conjugation is known as glucuronidation because it involves the addition of glucuronic acid. The enzyme responsible for this is known as uridine diphosphoglucuronate-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1)

Bilirubin excretion

Once bilirubin has undergone glucuronidation, it is excreted into bile against its concentration gradient through bile canalicular membrane transporters such as multidrug resistance protein 2.

Bilirubin degradation

Bile is released into the gastrointestinal tract. Within the gastrointestinal tract, bilirubin is deconjugated by intestinal bacteria to a group of compounds known as urobilinogens. Urobilinogens may be further oxidised and some are reabsorbed via the enterohepatic circulation. These additional products include urobilin and sterocobilin, which are what give faeces its characteristic brown colour. A small percentage of the reabsorbed urobilinogens is excreted into urine. These oxidised urobilinogens account for the colored compounds that contribute to the yellow color of urine.

Differential diagnosis

The causes of jaundice can be classically categorised into pre-hepatic, hepatic and post-hepatic.

Jaundice may be caused by an excess breakdown of red blood cells (i.e. haemolysis), intrinsic liver disease (e.g. cirrhosis) or obstruction to bile flow (e.g. gallstones). We can categorise these causes into pre-hepatic, hepatic and post-hepatic.

Some causes are benign and do not require any treatment while other causes can be life-threatening. Therefore, the identification of jaundice requires a full clinical assessment and a series of investigations to determine the exact cause.

Pre-hepatic

Any cause of increased bilirubin production can lead to jaundice. The major pre-hepatic cause is haemolysis, which refers to the breakdown of red blood cells. Example haemolytic disorders include:

- Sickle cell disease

- Hereditary spherocytosis

- Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia

- Iatrogenic (e.g. metallic heart valve)

Haemolysis may be extravascular occurring within the reticuloendothelial system (e.g. spleen, liver, bone marrow) or intravascular occurring within the circulation. Haemoglobin in the circulation binds to haptoglobin and is taken to the liver or kidneys where it is metabolised to bilirubin.

Pre-hepatic jaundice is characterised by:

- Anaemia (due to haemolysis)

- Unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia (due to excess bilirubin that has not yet been conjugated in the liver)

- Markers of haemolysis (e.g. raised lactate dehydrogenase, raised reticulocytes, low haptoglobin)

Hepatic

Jaundice may be the first indication of serious underlying liver disease.

The liver is important for both processing bilirubin (i.e. conjugation to make it more water-soluble) and excreting it into bile after conjugation. Therefore, hepatic causes of jaundice can be divided into two types:

- Unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia: abnormal bilirubin processing. Generally due to abnormal enzyme activity (often inherited)

- Conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia: abnormal bilirubin excretion. Generally due to intrinsic liver disease

Unconjugated

Firstly, it is important to differentiate hepatic causes of unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia from pre-hepatic causes. In the absence of markers of haemolysis (e.g. anaemia, low haptoglobin), unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia is very likely to be hepatic in origin.

In the liver, the enzyme uridine diphosphoglucuronate-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1), which is often shortened to glucuronosyltransferase, is needed for the conjugation of bilirubin with glucuronic acid. Reduced activity of this enzyme can lead to an increase in unconjugated bilirubin.

Reduced or absent activity of glucuronosyltransferase may be inherited or acquired:

- Inherited: Gilbert’s syndrome (10-30% activity), Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 (absent activity), Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 (<10% activity)

- Acquired: Hyperthyroidism, Ethinyl estradiol, antibiotics (e.g. gentamicin at high serum levels), anti-retroviral drugs, others

Gilbert syndrome is characterised by isolated unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia and typically presents around the time of puberty. Crigler-Najjar syndrome has a more severe presentation in the neonatal period due to severely reduced or absent activity. For more information see our Gilbert syndrome note.

Conjugated

A variety of hepatic disorders can lead to impaired excretion of bilirubin and conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia. Bilirubin excretion is an important synthetic function so elevated levels is a serious finding. Importantly, conditions that damage the liver parenchyma (e.g. alcohol) may actually cause a mix of unconjugated and conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia.

Virtually any cause of liver disease can lead to jaundice. Several examples are listed below, but this is not an exhaustive list:

- Hepatocellular injury: viral hepatitis, alcohol-related liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, hereditary haemochromatosis, medications, other causes of cirrhosis

- Infiltrative disorders: sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, tuberculosis

- Malignancy: due to infiltration or a paraneoplastic syndrome

- Inherited disorders: Rotor syndrome, Dubin-Johnson syndrome, Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC). These conditions are due to inherited mutations in genes important in the excretion of conjugated bilirubin

Cholestatic liver diseases (e.g. primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis) can be confusing because they primarily affect the biliary system (e.g canaliculi and/or bile ducts) leading to cholestasis. Cholestasis refers to poor bile flow and is essentially a cause of post-hepatic jaundice (i.e. obstruction). However, slow bile flow causes a build-up of potentially toxic substances (e.g. bile acids) that can damage hepatocytes leading to hepatocellular injury, and over time, cirrhosis.

Post-hepatic

The principal mechanism of post-hepatic jaundice is biliary obstruction. Obstruction may occur anywhere along the biliary tree from the small bile ducts to the larger extrahepatic ducts. Obstruction to flow through the small hepatic bile ducts is often referred to as ‘intrahepatic cholestasis’. Obstruction to flow in the larger bile ducts is usually referred to as extrahepatic obstruction.

Classic causes of post-hepatic jaundice include:

- Cholestatic liver diseases (e.g. primary sclerosing cholangitis): can lead to cholestasis and stricturing of the bile ducts

- Choledocholelithasis (i.e. gallstones)

- Malignancy (e.g. head of pancreas tumour): mass be intraluminal or caused by extrinsic compression

- Parasitic infections

- Mirizzi's syndrome: common hepatic duct obstruction caused by extrinsic compression from an impacted stone in the cystic duct or infundibulum of the gallbladder

Post-hepatic jaundice is characterised by:

- Elevated conjugated bilirubin

- Cholestatic liver enzyme elevation (e.g. predominant rise in alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase)

- Evidence of obstruction on imaging

History

The cardinal feature of jaundice is a patient (or carer/relative) noticing a yellow discolourisation of the skin and/or sclera.

Jaundice is usually the presenting feature after a patient (or carer/relative) notices a change in the colour of the skin and/or sclera. It is important to take a comprehensive history to determine the underlying cause. We discuss some of the important aspects of the history below.

Associated symptoms

Pain is a commonly associated feature and classically seen in obstructive jaundice (i.e. due to gallstones) or acute hepatitis. Pain associated with hepatobiliary problems is classically described as right upper quadrant pain and often radiates towards the back. Nausea and vomiting may also accompany the pain.

Painless jaundice is concerning for underlying malignancy, particularly if associated with fatigue and weight loss. The classic presentation of painless jaundice, in the absence of features of chronic liver disease, is a tumour in the head of the pancreas causing obstruction of the common bile duct.

Fever is another common feature and may suggest cholecystitis or cholangitis. It may be associated with malaise, anorexia and rigors. Pruritus is another common associated feature. This may be particularly problematic in patients with underlying cholestatic liver disease such as primary biliary cholangitis.

Risk of liver disease

The risk of liver disease should be determined in the clinical history. Key questions include alcohol consumption, drug use (including injecting), blood transfusions (especially if received abroad), tattoos, foreign travel, family history of liver disease and practice of unsafe sex.

Dark urine, pale stools

Patients with biliary obstruction (e.g. intrahepatic cholestasis or extrahepatic obstruction) can develop a classic presentation of dark urine and pale stools.

Dark urine occurs because conjugated bilirubin is water-soluble and easily excreted by the kidneys leading to discolouration. Pale stools occur because the breakdown products of bilirubin, once they enter the intestines, gives faeces its characteristic brown colour. The absence of bilirubin passing into the intestines leads to a pale appearance.

While suggestive of post-hepatic jaundice, these features may also be seen in acute hepatic disorders so they are not a reliable marker to differentiate between the causes of jaundice.

Examination

Assess for any features of underlying chronic liver disease.

The physical examination can give a lot of information about the suspected cause (e.g. pre-hepatic, hepatic or post-hepatic). Basic bedside assessments such as looking for muscle wasting and body habitus can tell us about the nutritional status of the patient. In particular, look for wasting of the facial muscles (e.g. temporalis). Cachexia (i.e. wasting due to chronic illness) may be a sign of malignancy or chronic liver disease.

Patients with haemolysis may appear pale due to associated anaemia and there may be splenomegaly on abdominal palpation. Classically there is a description of a ‘lemon tinge’ due to milder jaundice in combination with anaemia.

There may be an obvious abdominal mass or lymphadenopathy on palpation suggestive of malignancy. Scratch marks may be present due to pruritus associated with jaundice.

Stigmata of chronic liver disease

There are a number of clinical features suggestive of advanced liver disease (i.e. cirrhosis), which are collectively referred to as ‘stigmata of chronic liver disease’. Among these, jaundice, ascites and encephalopathy are all features of decompensated cirrhosis (i.e. the liver has lost all its capacity to carry out its usual functions).

Stigmata include:

- Caput medusa: distended and engorged superficial epigastric veins around the umbilicus

- Splenomegaly: enlarged spleen

- Palmar erythema: red discolouration on the palm of the hand, particularly over the hypothenar eminence

- Dupuytren's contracture: thickening of the palmar fascia. Causes painless fixed flexion of fingers at the MCP joints (most commonly ring finger)

- Leuconychia: the appearance of white lines or dots in the nails. Sign of hypoalbuminaemia

- Gynaecomastia: development of breast tissue in males. Reduced hepatic clearance of androgens leads to peripheral conversion to oestrogen

- Spider naevi: type of dilated blood vessel with central red papule and fine red lines extending radially. Due to excess oestrogen. Usually found in the distribution of the superior vena cava

Courvoisier’s law

This law also referred to as a sign or syndrome, essentially states that painless jaundice in the presence of a palpable gallbladder is unlikely to be due to gallstones. This highlights the fact that an obstructed biliary system in the absence of pain is highly concerning for malignancy.

Investigations

Interpretation of liver function tests is important to determine the cause of jaundice.

Investigations are essential to determine the underlying cause of jaundice. Liver function tests will confirm the presence of jaundice by highlighting an elevated bilirubin. The remaining enzymes that come as part of liver function tests will help to localise the problem to a pre-hepatic, hepatic or post-hepatic cause.

Subsequent investigations are needed to pinpoint the exact cause that will usually involve a liver screen (series of investigations to test for causes of liver disease) and imaging to exclude obstruction, assess for cirrhosis and look for mass lesions.

Basic blood tests

Any patient with jaundice needs a series of basic investigations:

- Full blood count: look for anaemia or features of chronic liver disease (e.g. low platelets). Raised white cell count may suggest infection (e.g. cholangitis)

- Renal function: acute liver abnormalities can be associated with renal dysfunction

- Liver function tests: to confirm raised bilirubin and look for the pattern of liver enzyme derangement

- Coagulation: a synthetic function of the liver

- CRP: would be raised in inflammatory/infectious causes (e.g. cholangitis, acute hepatitis)

NOTE: the bilirubin given as part of liver function tests is usually the total bilirubin. It is important to request an unconjugated or split bilirubin to look at the proportion of unconjugated to conjugated bilirubin.

Haemolysis screen

If the cause is suspected to be pre-hepatic then it is important to send off a haemolysis screen. This refers to a series of blood tests that acts as markers of haemolysis. These include:

- Reticulocytes

- Blood film

- Lactate dehydrogenase

- Haptoglobin

- Unconjugated bilirubin

Liver function tests (LFTs)

This forms the backbone of the assessment of jaundice.

LFTs refer to a series of blood tests that can help to investigate abnormalities within the hepatobiliary system. Theses include:

- Alanine transaminase (ALT)

- Asparate transaminase (AST)

- Alkaline phosphatase (ALP)

- γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (gGT)

- Bilirubin

- Albumin

Hepatic enzymes include ALT, AST, gGT, and ALP. These enzymes are found within the liver and are released when the liver is injured. Therefore, they act as markers for injury/inflammation. The pattern of enzyme elevation helps to determine the cause of jaundice:

- Pre-hepatic: typically normal enzymes with an isolated elevation in unconjugated bilirubin

- Hepatic (i.e. liver parenchyma): usually a predominant rise in ALT/AST > ALP/gGT

- Post-hepatic (i.e. biliary problem): usually a predominant rise in gGT/ALP > ALT/AST

Imaging

Imaging is essential in any patient presenting with jaundice. It helps to assess the liver architecture, rule out an obstruction in the biliary system, and look for any surrounding lesions (e.g. head of pancreas mass). The choice of imaging depends on the suspected cause and patient demographics. In a young patient with suspected gallstones, it may be most appropriate to perform an ultrasound. In an older patient with suspected cancer, it may be most appropriate to perform a CT scan.

Options include:

- Liver ultrasound

- CT abdomen/pelvis

- MRI liver

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

Liver screen

It is usually difficult to determine the cause of jaundice based on the history and examination alone. Therefore, when patients present with abnormal liver function tests (e.g. jaundice due to high bilirubin) they undergo a non-invasive liver screen to try and identify the cause. A non-invasive liver screen refers to screening questions and biochemical tests to assess patients with suspected liver disease. This screen includes tests for viruses, autoimmune diseases, and other rare causes of inflammation. For more information see our Chronic liver disease note.

Key tip

ERCP is a commonly utilised diagnostic and therapeutic procedure for post-hepatic jaundice.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is an invasive endoscopic procedure that involves passing an endoscope down to the duodenum and then gaining access to the biliary system via the Ampulla of Vater. Contrast can be injected to assess the biliary tree and a number of interventions can be completed to relieve an obstruction.

There are many indications for ERCP but it is classically completed in patients with jaundice secondary to an obstruction (i.e. stone in the common bile duct or tumour compressing the common bile duct). Via ERCP, stones can be removed and obstructions can be relieved using plastic or metal stents. Biopsies and brushings can also be taken to investigate for malignancy.

Last updated: July 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback