Infective conjunctivitis

Notes

Overview

Infective conjunctivitis refers to conjunctival inflammation occurring secondary to viral, bacterial or parasitic infection.

Patients with conjunctivitis often present with discomfort, eye discharge and conjunctival erythema. The infections may be acute or chronic:

- Acute: features resolve within four weeks

- Chronic: features persist for more than four weeks

Infective conjunctivitis is very common, accounting for an estimated 1% of all GP consultations.

Infections are typically self-limiting, resolving without long-term sequelae, and can be managed in primary care. In certain circumstances or where there is diagnostic uncertainty referral to ophthalmology may be warranted.

Aetiology

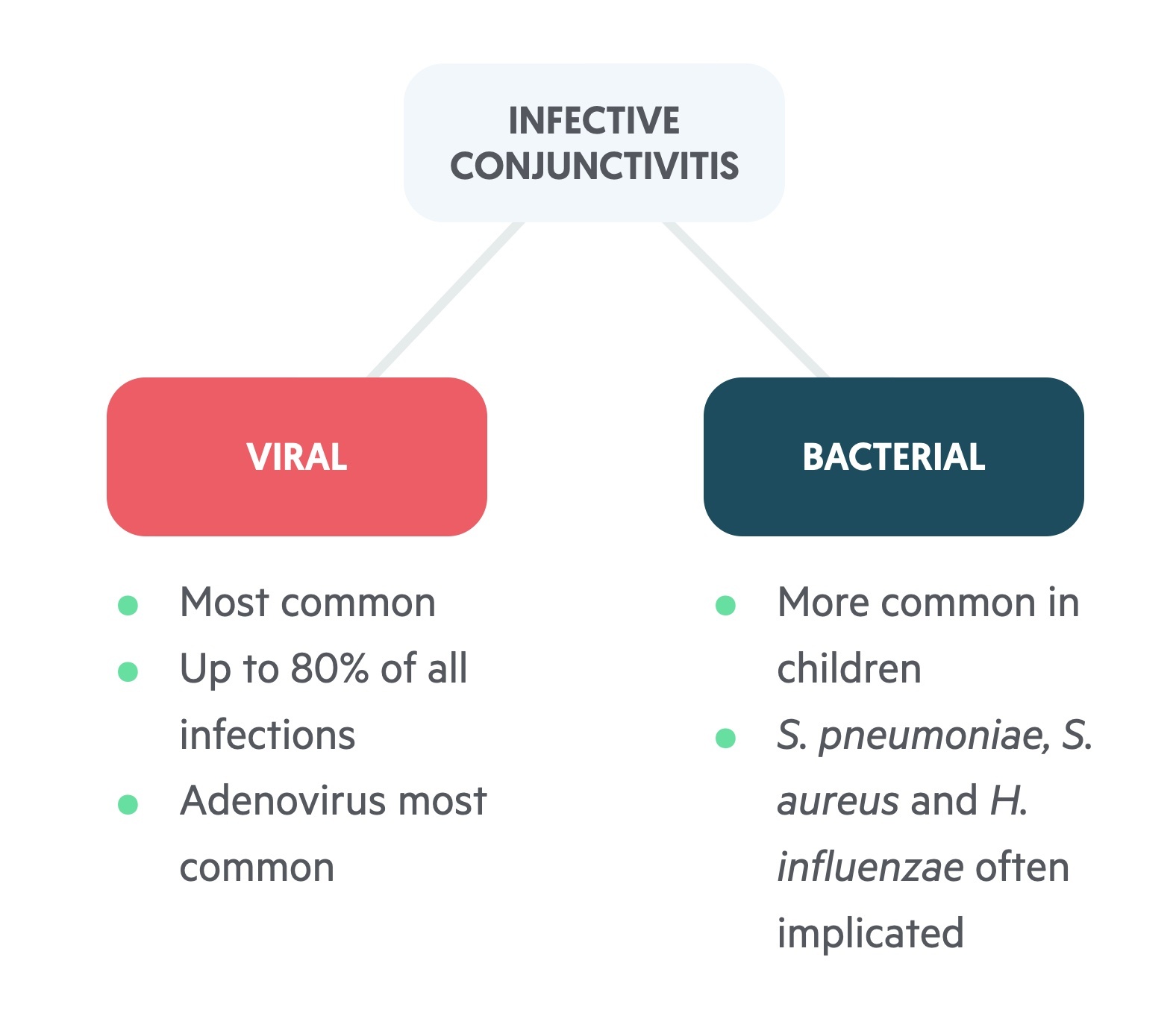

Viral infection is the leading cause of infective conjunctivitis.

Viral conjunctivitis: the leading cause of infective conjunctivitis, thought to account for up to 80% of cases. Adenovirus is the most commonly identified pathogen, responsible for an estimated 65-90% of viral conjunctivitis. Other causes include Herpes simplex, Molluscum contagiosum, Varicella zoster and Epstein-Barr virus.

Bacterial conjunctivitis: the second most common cause of infective conjunctivitis, it is more commonly seen in children and the elderly. Commonly identified pathogens include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus and Haemophilus influenzae.

Specific forms

There are a number of specific forms of infective conjunctivitis to be aware of.

These specific forms differ from your typical simple cases of infective conjunctivitis in their clinical presentation, management and complications. Four to be aware of are:

- Hyperacute conjunctivitis: a rapidly progressive and severe infective conjunctivitis that is normally caused by Neisseria gonorrhoea and Neisseria meningitidis. It is characterised by an eye that produces large amounts of purulent discharge. The infection is severe and potentially sight-threatening.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) conjunctivitis: this is conjunctivitis caused by the HSV. Typically HSV type 1 is implicated but type 2 is more often seen in neonatal cases (from contamination during vaginal delivery). The primary infection of the virus is normally asymptomatic but it becomes dormant and can reactivate later causing conjunctivitis. It is normally unilateral, causing a red-eye and vesicular lesions on the eyelid.

- Ophthalmia neonatorum: refers to conjunctivitis occurring in the first 28 days of life. It may be infective (often from contamination from the maternal genital tract) or non-infective. Bacterial infection is common with Chlamydia trachomatis is implicated in 20-40% of cases with Neisseria gonorrhoea less commonly isolated. Non-sexually transmitted bacteria account for up to 50% of cases with common pathogens including Streptococcus spp, Staphylococcus spp and Haemophilus spp.

- Trachoma: this refers to a chronic keratoconjunctivitis. Keratoconjunctivitis refers to both keratitis (inflammation of the cornea) and conjunctivitis. Trachoma is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and is most commonly seen in children in sub-Saharan Africa. It is the leading cause of infective blindness worldwide.

Clinical features

Patients present with a watery or discharging, red eye. Discomfort and pruritus is common.

General features

Discomfort is common and patients may describe the sensation of grittiness in the eye.

- Conjunctival erythema (red eye)

- Watery eye

- Irritation/discomfort

- Pruritus

Differentiating between viral and bacterial infection is difficult clinically. Purulent discharge and the absence of pruritus points towards bacterial infection.

Hyperacute conjunctivitis

- Red-eye

- Significant purulent discharge

- Pre-auricular lymphadenopathy

Herpes simplex

- Red-eye

- Watery eye

- Vesicular lesions on eyelid

Red flags

There are a number of red flags that should prompt referral to ophthalmology.

High index of suspicion is required for signs of severe infection or alternative diagnosis, these require urgent medical/ ophthalmological assessment:

- Significant pain

- Photophobia

- Visual changes (including wavy lines, flashes)

- Reduction in visual acuity

- Use of contact lenses

- Associated headache

- Baby less that 30 days with red/sticky eyes

- Trauma or foreign body

- Significant discharge (indicative of gonococcal infection)

- Herpes infection

Management

The majority of episodes of infective conjunctivitis are self-limiting.

Clinicians need to be aware of patients at risk of complications or alternative diagnoses who need referral to ophthalmology.

Acute (non-herpetic) viral conjunctivitis

The diagnosis should be explained. In uncomplicated cases, patients should be reassured that the condition is normally self-limiting.

- Symptomatic relief: cool compress and lubricating eye drops may help settle symptoms. The eye can be cleaned with soaked (boiled and cooled water or sterile saline) cotton wool.

- Prevent spread: patients should try to avoid spread to others (they are infective for up to 14 days) and the contralateral eye. Good hand hygiene and the use of separate towels should be advised.

- Safety netting: patients should be given a clear explanation of when they should return or seek urgent medical attention. This includes changes to vision, eye pain, headache, photophobia, worsening purulent discharge or persistent symptoms.

Investigations may be considered, particularly in those who return. At this point, viral PCR and bacterial culture can be sent and empirical topical antibiotics commenced. Consider referral to ophthalmology particularly if persistent for more than 7-10 days.

Acute bacterial conjunctivitis

The diagnosis should be explained. In uncomplicated cases, patients should be reassured that the condition is normally self-limiting.

- Symptomatic relief: cool compress and lubricating eye drops may help settle symptoms. The eye can be cleaned with soaked (boiled and cooled water or sterile saline) cotton wool.

- Prevent spread: patients should try to avoid spread to others (they are infective for up to 14 days) and the contralateral eye. Good hand hygiene and the use of separate towels should be advised.

- Safety netting: patients should be given a clear explanation of when they should return or seek urgent medical attention. This includes changes to vision, eye pain, headache, photophobia, worsening purulent discharge or persistent symptoms.

Antibiotics may be required, either immediately or with a delayed prescription to be taken if symptoms don’t resolve.

- Chloramphenicol drops/ointment: first-line, may be given either as drops or an ointment, typically for 5 days.

- Fusidic acid eye drops: used second line, typically given for 7 days.

Patients should be given safety net advice including to return or seek urgent medical attention if they develop changes to vision, eye pain, headache, photophobia, worsening purulent discharge or persistent symptoms. They should be followed up routinely.

Investigations may be considered, particularly in those who return. At this point, viral PCR and bacterial culture can be sent if not already. Consider referral to ophthalmology particularly if persistent for more than 7-10 days.

Contact lenses

The cornea should be assessed using topical fluorescein drops. Refer any patient with suspected corneal involvement.

Patients who use contact lenses (with no evidence of complication) should cease their use until the condition has completely resolved and follow the treatment discussed above.

Referral

Referral to ophthalmology may be required typically where patients are at risk of severe disease and complications or where a serious differential is suspected.

- Severe disease or differential: patients with suspected severe disease, evidence of corneal ulceration, significant keratitis or pseudomembrane formation require referral. As do those with red flags (see above) or where there is suspicion of an alternative and severe diagnosis (e.g. periorbital or orbital cellulitis).

- Aetiology: those in whom the aetiology is confirmed or suspected sexually transmitted pathogen or herpes need ophthalmology assessment.

- Patient factors: those with recent intraocular surgery or with a severe underlying systemic condition (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis or HIV).

- Contact lenses: in patients who use soft contact lenses with suspected corneal involvement immediate assessment is required. Their contact lenses should be taken with the patient to the eye hospital as specialist tests may be needed.

- Ophthalmia neonatorum: all neonates with ophthalmia neonatorum should have a specialist assessment.

Last updated: November 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback