Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Notes

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by persistent symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is considered one the neurodevelopmental disorders such as Autism spectrum disorder. It is characterised by persistent symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.

- Inattention: may manifest as forgetfulness, being easily distracted, difficulty organising and prioritising tasks, seeming not to listen, and losing belongings.

- Hyperactivity: may present as excessive fidgeting, difficulty sitting still, restlessness, and being overly talkative.

- Impulsivity: may manifest as difficulty waiting their turn and interrupting others.

These three hallmark symptoms are present across several settings (e.g. work, school, home) and negatively impact a person’s functioning. ADHD is usually diagnosed in children and young people but may also be diagnosed in adults, where the diagnosis has previously been missed.

These notes focus on the diagnosis and management of ADHD in children, young people, and adults.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of ADHD varies considerably throughout the world.

The global prevalence of ADHD in children is estimated to be 5%, whereas in the US the prevalence is estimated at 10%. In the UK, the prevalence of ADHD in adults is estimated at 3-4%.

ADHD is more commonly diagnosed in boys than girls (3:1). This difference is thought to be due to ADHD being under-recognised in girls. Boys present commonly with more disruptive hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, whereas girls often present with less noticeable symptoms of inattention.

There are 3 subtypes of ADHD:

- Combined inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive = 60%

- Inattentive = 25%

- Hyperactive-impulsive = 15%

Aetiology & risk factors

Patients with ADHD have been found to have lower levels of the neurotransmitters noradrenaline and dopmaine.

The exact cause of ADHD remains unknown, however, alterations in neurotransmitters in the brain have been observed.

Reduced levels of noradrenaline and dopamine in certain parts of the brain are thought to significantly contribute to the manifestation of ADHD symptoms. A key area of the brain, thought to have lower levels of these neurotransmitters, is the pre-frontal cortex. Functions of the pre-frontal cortex include organisation, planning, decision-making, impulse control, regulating emotions, and sustaining attention. These are all functions that are impaired in ADHD.

Risk factors

ADHD is likely to be the consequence of a complex interaction between multiple environmental and genetic factors. Risk factors for ADHD include:

- Family history: of ADHD or other neurodevelopmental disorders.

- Other neurodevelopmental disorders (autism spectrum disorder, learning disability, specific learning difficulties).

- Low birth weight or pre-term delivery.

- Looked after children and young people.

- Oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, or mood disorder.

- Adults with a mental health condition or history of substance misuse.

- People with epilepsy.

Clinical features & diagnosis

ADHD is a clinical diagnosis based on the DSM-V or ICD-11 diagnostic criteria.

Both the DSM-V and ICD-11 can be used as frameworks to aid diagnosis and are largely similar in their approach. In these notes, we have chosen to outline the diagnosis of ADHD using the DSM-V criteria:

In ADHD, there is a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development. The presence of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity behaviour is based on the list of symptoms set out below. These symptoms should have been present in childhood before the age of 12 years old. They are not within the normal range of the child's developmental level. The symptoms have been present for at least six months, and they are present in ≥2 settings (home, school, work, other activities). Collectively, the symptoms should directly interfere with or negatively impact social and academic/occupational functioning and they are not better explained by another mental disorder.

Inattention symptoms

≥6 of the following symptoms need to be present:

- Careless mistakes: fails to give close attention to detail or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or during other activities.

- Difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities (e.g., difficulty remaining focused during lectures, conversations, or lengthy reading).

- Difficulty listening: doesn’t seem to listen when spoken to directly (e.g. mind seems elsewhere even in the absence of any obvious distraction).

- Doesn’t follow instructions and fails to finish schoolwork chores or duties in the workplace (e.g. starts tasks but quickly loses focus and is easily sidetracked).

- Difficulty organising and prioritising tasks and activities (e.g. difficulty managing sequential tasks, difficulty keeping belongings in order, messy and disorganised work, poor time management, failure to meet deadlines)

- Disliking tasks requiring sustained concentration: often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort (e.g. schoolwork, preparing reports, completing lengthy forms).

- Loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g. school materials, pencils, books, wallet, keys).

- Easily distracted by irrelevant stimuli or own thoughts.

- Forgetful in daily activities (e.g. doing chores, running errands, returning calls, paying bills, keeping appointments).

Hyperactivity and impulsivity symptoms

≥6 of the following symptoms need to be present:

- Fidgety: often fidgets with or taps hands or feet, squirms in seat.

- Unable to sit still: often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected (e.g. in classroom or workplace).

- Runs about or climbs in situations where it is inappropriate. In adolescents or adults, this may be limited to feeling restless.

- Noisy: often unable to play or engage in leisure activities quietly.

- “On the go” or acting restlessly as if “driven by a motor” (e.g. unable or uncomfortable sitting still for extended periods such as in restaurants, in class, or in meetings).

- Talks excessively.

- Blurts out answers before the question has been completed (e.g., can’t wait turn in the conversation, completing other sentences).

- Difficulty waiting their turn (e.g. waiting in line).

- Interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g. butts into others’ conversations, games, or activities, may start using other people's things without asking or receiving permission, may intrude into or take over what others are doing).

DSM-V ADHD subtypes

The DSM-V has specifiers that divide ADHD into three subtypes:

- Combined presentation: over the last 6 months meets criteria for inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity.

- Predominantly inattentive presentation: over the last 6 months meets criteria for inattention but does not meet criteria for hyperactivity-impulsivity.

- Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive presentation: over the last 6 months meets criteria for hyperactivity-impulsivity but does not meet criteria for inattention.

ADHD assessment

A diagnosis of ADHD is made clinically and requires a detailed clinical assessment including developmental and psychiatry history.

ADHD is a clinical diagnosis and is based on:

- A detailed clinical assessment: focus on the symptoms of ADHD and their impact across different settings.

- A full developmental and psychiatric history.

- Observer reports and assessments of the person's mental state: often from parents and school.

Children and young people

Assessment considerations in children and young people: NICE Guidelines do not advise universal screening for ADHD. For children and young people exhibiting features of ADHD that persist and interfere with functioning, the advice is to refer to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) for detailed assessment. The diagnosis of ADHD is always made in secondary care.

Conner’s rating scale and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire are useful tools that are commonly used to aid ADHD assessment in children and young people.

Adults

Adults that do not have a childhood diagnosis of ADHD, should be referred for assessment if there are symptoms of ADHD that:

- Began during childhood and have persisted throughout life.

- Not explained by other psychiatric diagnoses.

- Associated with moderate or severe psychological, social, educational, or occupational impairment.

Differential diagnosis

Frequent tics secondary to Tourette's disorder can be mistaken for fidgetiness in ADHD.

- Autism spectrum disorder: social difficulties tend to be associated with both. Children with ASD may have emotional outbursts because of an inability to tolerate change from their expected routine, whereas children with ADHD may have tantrums due to impulsivity and restlessness.

- Tourette’s disorder: frequent tics can be mistaken for fidgetiness occurring in ADHD.

- Auditory or visual impairment: inattentiveness may be secondary to hearing and vision problems.

- Absence seizures: may be responsible for discrete episodes of inattention.

- Specific learning disorder: inattention related to a specific task (e.g. reading) but inattention not pervasive.

- Oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder: may both present with disruptive behaviours and be co-morbid with ADHD.

- Anxiety disorders: inattention in anxiety disorders is due to excessive worrying.

- Depressive disorders: also present with poor concentration.

- Borderline personality disorder: both conditions are characterised by impulsivity. In borderline PD, impulsive behaviours are often self-damaging and there is also instability in their interpersonal relationships, self-image, and emotions.

General management

The management of ADHD needs to be tailored to the individual’s needs and circumstances.

The main management strategies for ADHD include psychoeducation, environmental modifications, talking therapies, and consideration of medication. The choice of these will depend on the age group of the patient.

Management in children (< 5 years old)

First-line treatment is usually an ADHD-focused group parent-training programme. If first-line fails, then advice should be obtained from a specialist ADHD service.

Do NOT offer medication for ADHD for any child under five years without a second specialist opinion.

Management in children and young people (5-18 years old)

Simple strategies for the management of ADHD in children and young people include group-based support for parents, communication with school, and environmental modifications.

- Group-based support for parents or carers: providing information on ADHD and advice on its management and helpful parenting strategies. Parents are educated on positive behavioural reinforcement which involves keeping the focus on praising and rewarding positive behaviours, thereby reinforcing positive behaviour changes. There is also education on the benefits of regular exercise and a healthy diet (NICE Guidelines advise against any specific or restrictive diets).

- Liaison with school and SENCO (Special Educational Needs Coordinator): may be able to implement helpful environmental modifications.

- Environmental modifications: particularly at home and school. These can minimise the impact of ADHD symptoms. Appropriate environmental modifications will be specific to the circumstances of each person with ADHD but might include reducing external distractions (e.g. using headphones, changing seating arrangements, sitting exams in smaller classrooms), promoting regular movement breaks, and reinforcing verbal requests with written instructions to help the individual stay on task. Task modifications may also be appropriate and tend to involve breaking down larger tasks into smaller “bitesize” chunks.

Medication should only be offered if ADHD symptoms are causing a persistent significant functional impairment after environmental modifications have been implemented and reviewed. Among young people, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) may be considered in those who have benefited from medication but whose symptoms are still causing significant impairment. CBT can help a young person develop problem-solving skills, self-control, active listening and social skills, and healthy ways of dealing with and expressing emotions.

Management in adults

Similar principles apply to adults around environmental changes. Medication should only be offered if ADHD symptoms are still causing a persistent, and significant, functional impairment after environmental modifications have been implemented and reviewed.

A structured supportive psychological intervention focused on ADHD may be considered for adults who have benefited from medication but whose symptoms are still causing significant impairment. Adults with ADHD may benefit from a course of CBT.

Pharmacological management

In children, young people, and adults, medication is indicated if ADHD symptoms cause significant impairment and persist despite environmental modifications.

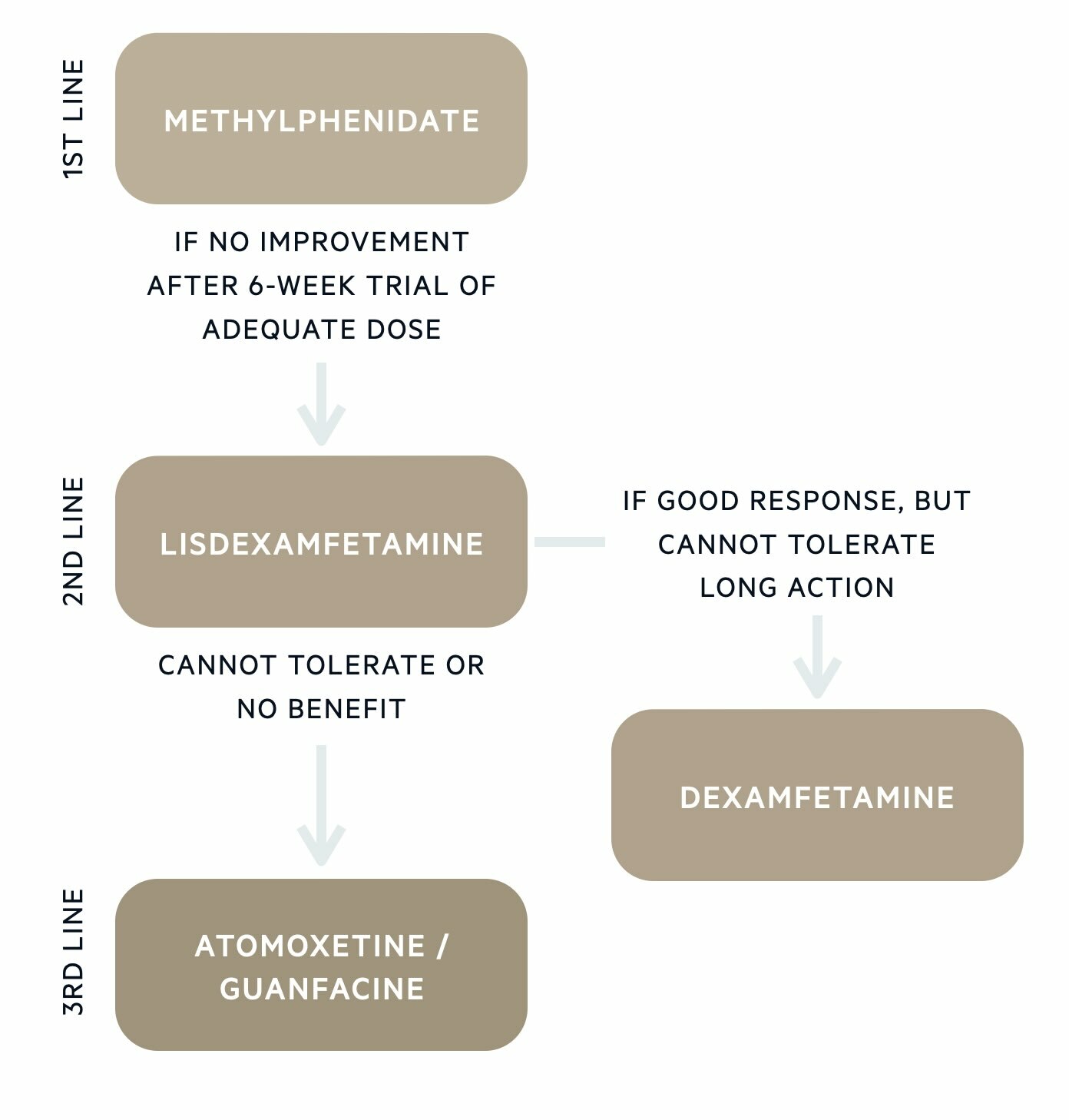

Treatment overview - children and young people

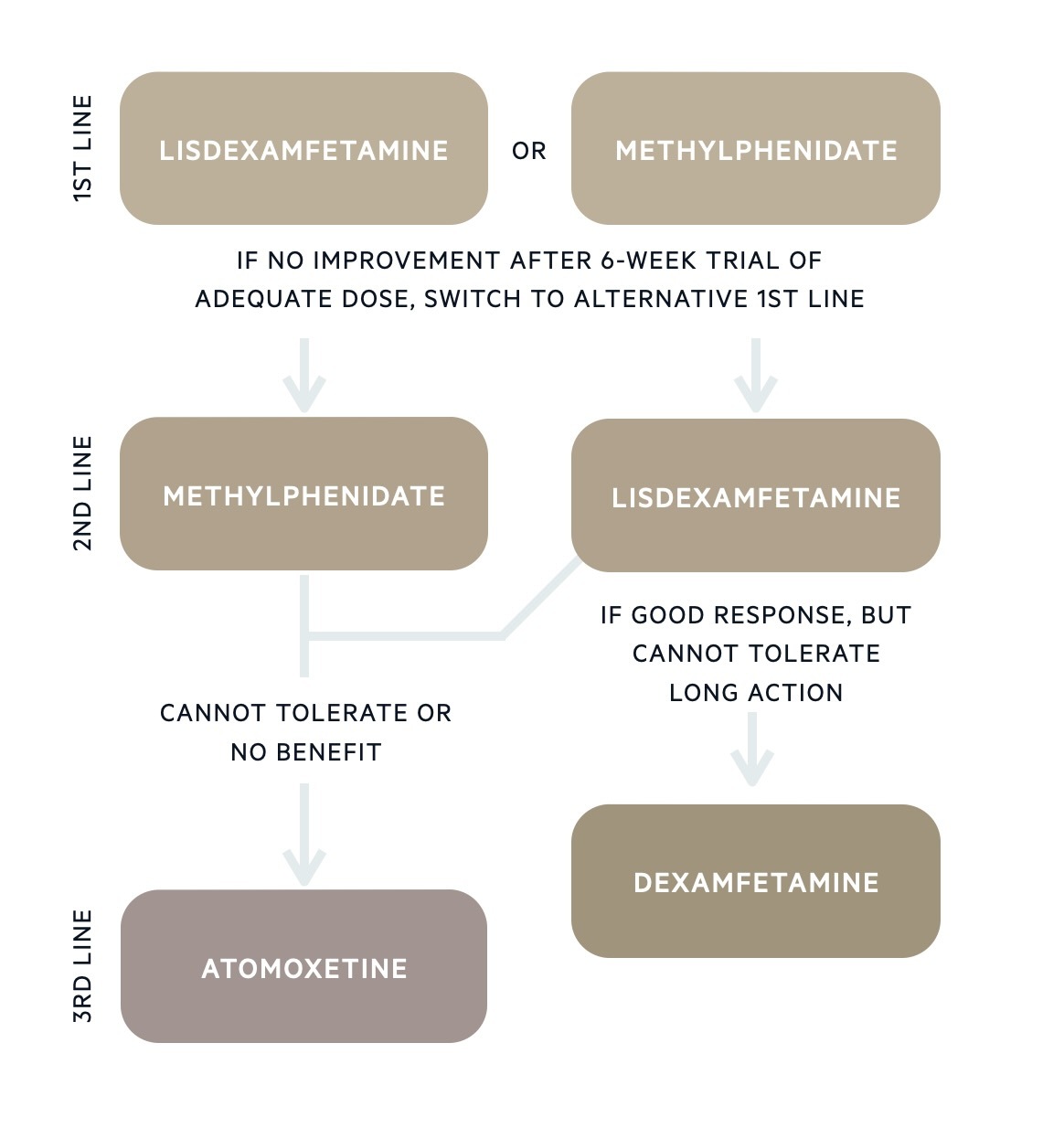

Treatment overview - Adults

Before initiation

Before starting a medication, a comprehensive physical health assessment should be completed:

- Medical history

- Current medication

- Height and weight (measured and recorded against normal range for age, height, and sex)

- Pulse and blood pressure

- Cardiovascular assessment: listen to heart sounds (no need for an ECG unless concern of increased cardiac risk).

A formal referral to cardiology before starting ADHD medication should be considered in the following circumstances:

- There is a history of cardiac pathology (history of congenital heart disease or previous cardiac surgery).

- There are symptoms suggestive of cardiac pathology (hypertension, shortness of breath or fainting on exertion, cardiac-sounding chest pain, signs of heart failure, heart murmur on chest auscultation, palpitations).

- There is a history of sudden death in a first-degree relative under 40 years suggesting a cardiac disease.

Stimulant medications

Stimulant medications are first-line in the pharmacological treatment of ADHD. They work by increasing levels of dopamine and noradrenaline. Stimulant medications licensed for the treatment of ADHD include methylphenidate, lisdexamfetamine, and dexamfetamine. Stimulant medications are Schedule 2 controlled drugs and are therefore subject to certain regulations (e.g. prescribers can supply a maximum of 30 days at a time).

Methylphenidate can be taken in immediate-release forms several times a day or once in the morning in a modified-release form. Commonly prescribed modified-release formulations include Medikinet XL (8-hour duration), Equasym XL (8-hour duration), Concerta XL (12-hour duration), and Delmosart XL (12-hour duration). It is also possible to use the modified-release preparation alongside a top-up of immediate-release later in the day to prolong the therapeutic effects.

Lisdexamfetamine is an inactive prodrug that is converted to the active form of dexamfetamine in the body. It has a long duration of action, lasting up to 13 hours. For those who benefit from lisdexamfetamine but cannot tolerate the longer duration of action, short-acting dexamfetamine can be prescribed.

Modified-release vs immediate-release preparations

Once daily modified-release preparations of stimulant medications tend to be the preferred option for multiple reasons including convenience, improved adherence, reduced stigma (as no need to take medications at school or workplace), avoiding the problem of storing and administering controlled drugs in schools, minimising the risk of stimulant misuse and diversion (more prevalent with immediate-release preparations).

Immediate-release preparations may be more suitable during initial titration to determine the correct dose or if flexible dosing regimens are needed. There is gradual titration of stimulant medication with regular review until the dose is optimised. The aim is to ensure good ADHD symptom management with minimal adverse effects.

Adverse effects

Adverse effects of stimulant medication include:

- Metabolic effects: decreased appetite, weight loss, growth suppression.

- Cardiovascular effects: hypertension, tachycardia, palpitations.

- Psychiatric effects: insomnia, anxiety, agitation, irritability, depression, mood swings.

- Gastrointestinal effects: dry mouth, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, or constipation.

- CNS effects: dizziness, tremor, headache.

Medication review

There are several monitoring and review requirements whilst individuals are taking medication for the treatment of ADHD. These include:

- Assessing efficacy: how well managed are ADHD symptoms.

- Monitor for adverse effects: described above.

- Measure height: every 6 months in children and young people (not applicable in adults)

- Measure weight: in children <10 years, measure weight every 3 months. In children >10 years and young people, measure weight at 3 months and 6 months after initiation, and then every 6 months. In children and young people plot the height and weight on a growth chart. In adults measure weight every 6 months.

- Check heart rate and blood pressure: before and after each dose change and every 6 months. If tachycardia (>120bpm) or hypertension, consider dose reduction and referral to an appropriate specialist.

A Shared Care Protocol is arranged with the GP, once the individual is stabilised on medication. This details an agreement between the GP and secondary care about who is responsible for the prescribing and monitoring of ADHD medication.

Where there are concerns about growth restriction in children and young people, a drug holiday might be considered. This is a planned treatment break for a defined period, often during school holidays, to allow for “catch-up” growth.

Non-stimulant medications

If the individual cannot tolerate the side effects of stimulant medication or there is an unsatisfactory response to two different stimulants, non-stimulant medication may be considered.

- Atomoxetine: selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI)

- Guanfacine: alpha-2a agonist

Atomoxetine is used in the treatment of ADHD in children, young people, and adults. It mainly works by increasing levels of noradrenaline (and to a lesser extent dopamine) in the brain. Adverse side effects have some crossover with stimulant medication and include loss of appetite, dry mouth, abdominal pain, anxiety, and headaches. Uncommon but severe adverse effects to warn patients and their parents about include increased suicidal ideation and liver dysfunction. Atomoxetine is cautioned in those with cardiovascular disease.

Guanfacine is licensed for the treatment of ADHD in children and young people. By activating alpha-2a receptors in the brain, it decreases sympathetic nervous system activity. Its action in the pre-frontal cortex is thought to improve symptoms of inattention and impulse control. Common side effects include hypotension, dizziness, tiredness, headache, dry mouth, and constipation. If guanfacine leads to sustained orthostatic hypotension or fainting episodes, the advice is to reduce the dose or switch to another medication.

Prognosis

It is estimated that 15% of children diagnosed with ADHD still meet the full criteria as an adult.

ADHD symptoms can persist into adulthood, improve, or entirely resolve. Around 15% of those diagnosed with ADHD as a child, still meet the full criteria for an ADHD diagnosis as an adult. Most enter a partial remission (65%); where some ADHD symptoms persist but there is less of a negative impact on daily life. Hyperactive-impulsive symptoms usually improve with age whereas symptoms of inattention tend to persist.

Last updated: January 2024

References:

DSM-V

NICE | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management | Guidance

Taylor, D. et al. (2018). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry (13th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback