Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

Notes

Overview

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is a life-threatening neurological disorder characterised by confusion, fever, and rigidity.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), is a rare, life-threatening disorder that is associated with the use of antipsychotic drugs (previously known as neuroleptic medications) but the exact cause is unknown.

The condition is characterised by altered mental status (i.e. confusion), fever, muscular rigidity, and dysautonomia (i.e. autonomic instability). It is associated with high mortality (~10-20%) and requires a low index of suspicion in patients presenting with characteristic symptoms (i.e. fever or rigidity) whilst taking antipsychotics. Treatment is largely supportive and most episodes will resolve within two weeks of removing the offending drug.

Epidemiology

NMS is estimated to affect up to 3% of patients taking antipsychotics.

NMS can occur at any age but predominantly occurs in young adults with a predilection towards men (2:1 ratio).

Aetiology & pathophysiology

All classes of anti-psychotics are associated with NMS, but it is most commonly seen with potent first-generation drugs.

The exact cause of NMS remains unknown. The condition is associated with the use of antipsychotics, but predominantly potent first-generation or ‘typical’ antipsychotics that are dopamine (D2) receptor antagonists. This includes haloperidol and fluphenazine. Rarely, other drugs with central dopamine antagonism can cause NMS (e.g. metoclopramide).

NOTE: NMS may be precipitated by a sudden dose reduction or withdrawal of antiparkinson agents (e.g. L-DOPA or dopamines agonists) in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Also termed neuroleptic malignant-like syndrome or parkinsonism hyperpyrexia syndrome.

Pathogenesis

It is suspected that central blockade of dopamine in the hypothalamus leads to hyperthermia and dysautonomia. Blockade of other central pathways can give rise to movement disorders (e.g. tremor, rigidity) that are well recognised side-effects even in the absence of NMS. Alternatively, there may be direct toxic effects of these drugs on peripheral muscle or disruption of the sympathetic nervous system. A genetic predisposition has also been suggested.

Natural history

NMS will typically occur within the first two weeks of starting an antipsychotic. However, it can occur after a single dose or after many years of using the medication. It is described as an 'idiosyncratic reaction’ (i.e. unpredictable and not dose-dependent). The majority of episodes will resolve within two weeks of stopping the drug, although patients may require a prolonged period of supportive management and mortality can be up to 20%.

Risk factors

Several factors have been associated with a higher risk of NMS.

- Higher antipsychotic doses

- High-potency antipsychotics

- Concomitant drug use (e.g. lithium)

- Depot formulations (i.e. long-acting)

- Acute medical illness (e.g. trauma, infection)

- Acute catatonia (state or immobility)

- Previous NMS

Several additional risk factors have been reported.

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics are widely used in the management of many mental health disorders.

Antipsychotics are widely used in a range of mental health illnesses. They are broadly divided into two categories:

- First-generation antipsychotics ('typicals'): dopamine (D2) receptor antagonists. Developed in the 1950s. Examples include phenothiazines, haloperidol, chlorprothixene. Also exert antagonism on noradrenergic, cholinergic, and histaminergic neurons.

- Second-generation antipsychotics ('atypicals'): serotonin-dopamine receptor antagonists. Examples include aripiprazole, risperidone, olanzapine.

First-generation antipsychotics are associated with more side-effects that include:

- Extrapyramidal: movement disorders like parkinsonism and dystonia

- Anti-cholinergic: dry mouth, dry eyes, constipation, urinary retention

- Anti-histamine: sedating

- Cardiovascular: prolonged QT interval, arrhythmias

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

Second-generation antipsychotics have a lower side-effect profile. However, there is still a risk of extrapyramidal side-effects, cardiovascular side-effects (e.g. prolonged QT interval, arrhythmias), and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. These medications are also associated with a high risk of weight gain and metabolic syndrome long-term.

Clinical features

NMS is characterised by altered mental status, fever, rigidity and autonomic instability.

The majority of patients with NMS will develop altered mental status followed by rigidity, fever, and finally dysautonomia.

- Altered mental status: often presents with agitation and delirium. Catatonia can be present. May progress to severe encephalopathy and coma.

- Rigidity: felt as a generalised increase in tone and may be severe. Other motor abnormalities can be present.

- Fever (>38º): less pronounced with second-generation antipsychotics. May be >40º.

- Dysautonomia: describes abnormalities in the autonomic nervous system. Thus, often termed ‘autonomic instability’. Leads to tachycardia, labile blood pressure, profuse sweating (i.e. diaphoresis) and/or arrhythmias.

Diagnosis & investigations

There should be a low index of suspicion for the presence of NMS in patients taking antipsychotics.

The diagnosis of NMS is usually made in patients who present with characteristic clinical features who are also taking antipsychotics. A supporting feature includes an elevated creatine kinase (CK) due to muscle rigidity (e.g. >1000-100,000 IU/L). CK may be normal if rigidity is not profound or the patient is early in the presentation.

If severe, muscle necrosis and rhabdomyolysis may develop. For more information see rhabdomyolysis notes.

Investigations

Investigations are useful to determine the severity of NMS and to exclude alternative causes.

- Bedside: observations, blood glucose, GCS monitoring, ECG, cardiac monitor

- Bloods: electrolyte derangements and acute kidney injury may be seen, particularly with the development of rhabdomyolysis (e.g. hypophosphataemia, hypomagnesaemia, hyperkalaemia, metabolic acidosis, sodium disruption). Mildly deranged LFTs and leucocytosis are common. CK is critical in all suspected cases.

- Imaging: Cerebral imaging is important to exclude an alternative cause of confusion (e.g. CT head / MRI head)

- Special: a lumbar puncture may be needed to exclude a cerebral infection or alternative cause of confusion (e.g. autoimmune encephalitis).

Differential diagnosis

Alternative diagnoses should be considered in any young patient presenting with new-onset confusion (e.g. encephalitis, drug intoxication, phaeochromocytoma). This list is very broad.

NMS is one of several ‘acute dysautonomias’ that should be considered in patients with these characteristic clinical features:

- Serotonin syndrome: similar presentation to NMS in association with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) drug use. Characterised by nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, shivering, hyperreflexia, myoclonus, and ataxia.

- Malignant hyperthermia: a rare genetic disorder characterised by hyperthermia, muscle rigidity, and dysautonomia in the setting of exposure to certain anaesthetic agents (e.g. succinylcholine) or vigorous exercise.

- Recreational drug use: both use of MDMA (i.e. ecstasy) and cocaine have been associated with an NMS-like syndrome.

Management

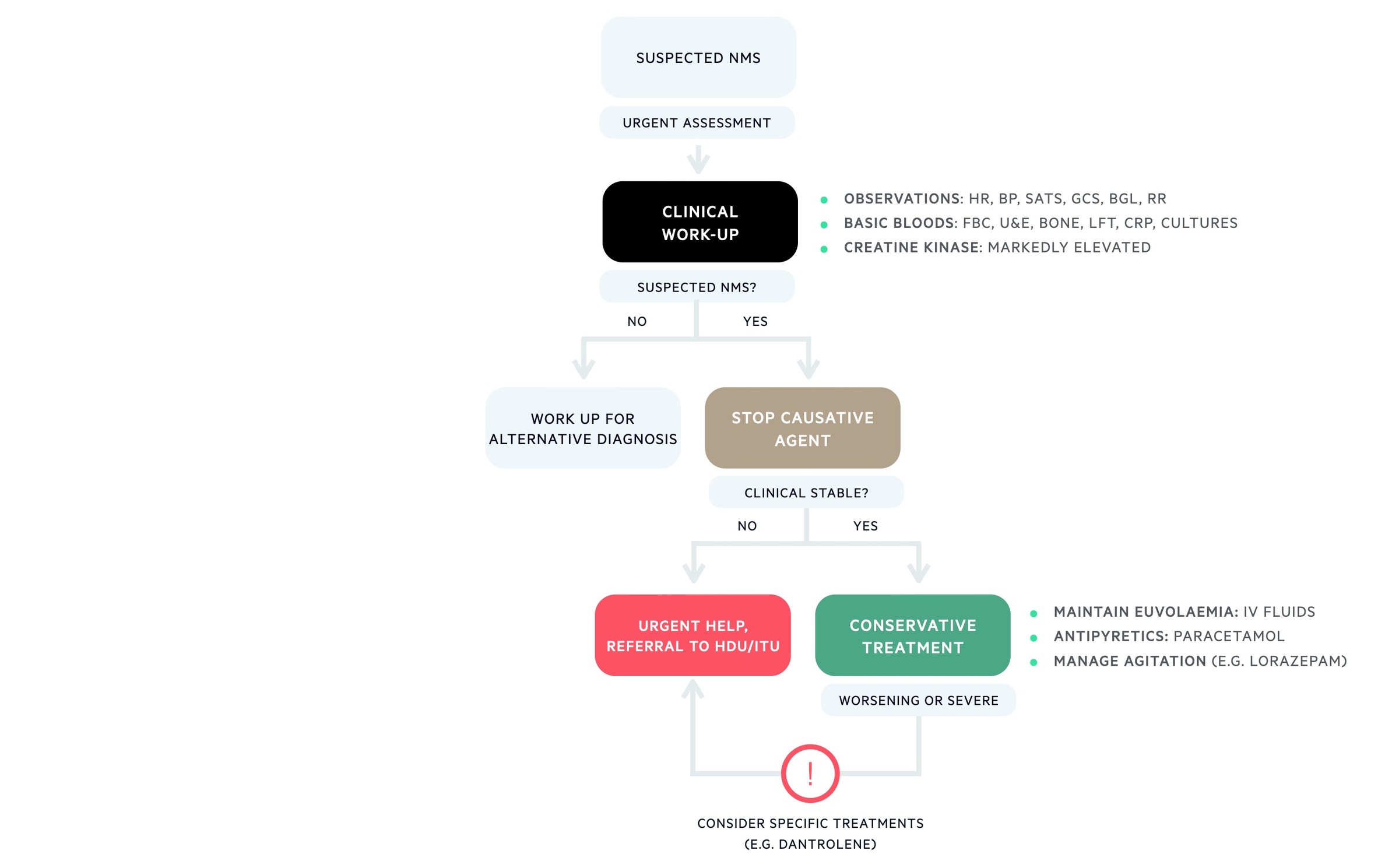

Management of NMS is largely supportive by managing complications, providing organ support, and stopping the antipsychotic.

The management of NMS depends on the severity of the presentation and is largely supportive. In severe cases, pharmacological agents can be used but the evidence for these is limited.

Supportive care

The antipsychotic drug should be stopped and patients should be monitored in the appropriate setting. Cardiac monitoring is usually required due to dysautonomia. Patients should be monitored and specific complications treated (e.g. electrolyte imbalance, acute kidney injury, rhabdomyolysis). In severe cases, patients may require organ support (e.g. intubation & ventilation, haemofiltration) and admission to intensive care.

Specific interventions that are helpful include intravenous fluids to maintain euvolaemic state, antipyretics and cooling blankets for hyperthermia, antihypertensive agents (e.g. clonidine) for profound hypertension and benzodiazepines as necessary for agitation.

Medical therapy

The use of specific medical therapies in NMS is controversial due to inconsistent evidence. In moderate to severe cases, dantrolene or bromocriptine may be used alongside supportive measures.

- Dantrolene: ryanodine receptor antagonist (causes skeletal muscle relaxation). Helps treat hyperthermia and rigidity.

- Bromocriptine: dopamine agonist. Prescribed to restore ‘dopaminergic tone’.

Follow-up

Following an episode of NMS, patients may require reinitiation of antipsychotics based on their mental health illness. This is a difficult decision and guidelines are available to help guide treatment. This should be a senior-led decision and guided by the psychiatrists.

Complications

Mortality from NMS ranges from 5-20% depending on the patient population studied.

NMS may be life-threatening and a number of severe complications can develop:

- Cardiac arrest

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Acute kidney injury

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Seizures

- Respiratory failure

- Venous thromboembolism

Last updated: March 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback