PICA

Notes

Introduction

Pica is a mental health condition where a person compulsively swallows non-food items.

Pica refers to the eating or craving of things that are not food and do not contain significant nutritional value. The term is derived from “pica-pica” the Latin word for the magpie; a bird with a tendency for gathering and eating an odd assortment of items. PICA is classified as an eating disorder but can also be the result of an existing mental disorder, or occur in the context of pregnancy or vitamin deficiencies.

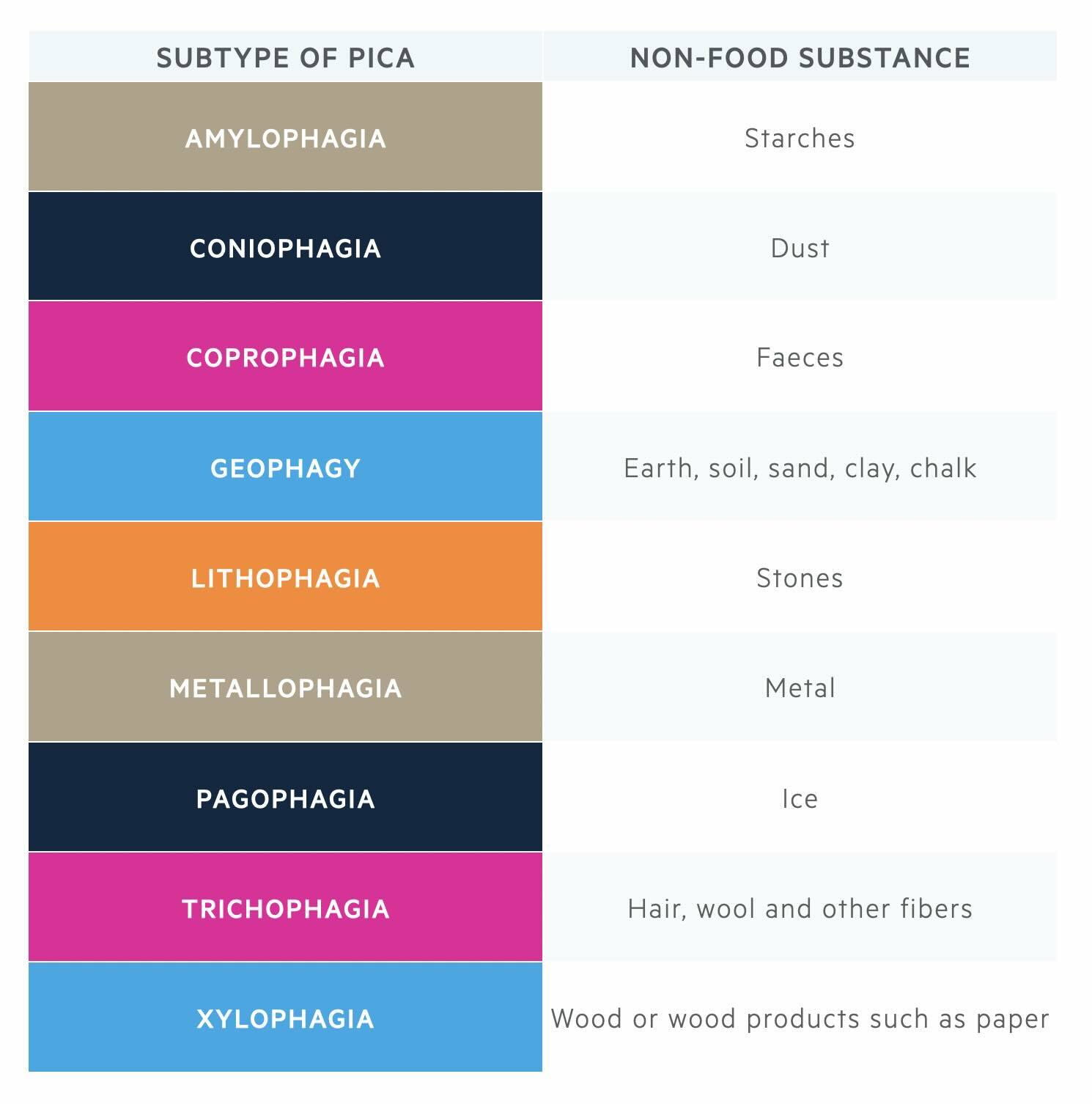

There are different types of pica, which can be characterised by the non-food substance eaten or craved:

Epidemiology

The prevalence of pica is difficult to establish because of differences in definition and reluctance of patients to acknowledge abnormal eating behaviours or cravings.

Pica most commonly affects pregnant women (25%), young children (20%), and individuals with an intellectual disability (10%). The most common types of pica include geophagia (eating earth, soil, clay, or sand), amylophagia (eating starches such as uncooked rice, flour, and cornstarch), and pagophagia (eating ice).

Aetiology & risk factors

In some parts of the world, the consumption of non-nutritive substances is culturally accepted and therefore this would not meet a diagnosis of pica.

Risk factors for pica include:

- Mental health disorders: intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, OCD, trichotillomania, stress.

- Medical conditions: iron deficient anaemia, other anaemias, malnutrition.

- Pregnancy

In some parts of the world, the consumption of non-nutritive substances is culturally accepted. For example, clay eating is common in parts of Africa and the Middle East as a traditional cultural activity.

Clinical features & diagnosis

Both the DSM-V and ICD-11 can be used as frameworks to aid the clinical diagnosis of pica.

PICA is characterised by the persistent consumption of non-food substances.

The diagnosis of pica is outlined below using DSM-V criteria:

- Persistent eating of non-nutritive, non-food substances for > 1 month.

- Inappropriate to the developmental level of the individual.

- Not a normal behaviour within the sociocultural context.

- If the eating behaviour occurs in the context of another mental disorder or medical condition, it is sufficiently severe to warrant additional clinical attention.

For the diagnosis of pica to be made, the individual must be > 2 years of age.

Management

The management of pica will depend on the underlying cause and co-morbidities.

There are currently no evidence-based treatments for pica and no NICE Guidelines. The literature advises testing for nutritional deficiencies and correcting any identified deficiencies with vitamin supplementation. It has been observed that concerning eating behaviours may resolve as deficiencies are corrected.

It is also suggested that behavioural therapies may be utilised, which can be helpful to:

- Identify triggers or cues for pica.

- Altering or removing any environmental triggers for pica: where possible, this should ensure that access to any potentially harmful pica items are restricted.

- Promoting alternative behaviours: this might include providing alternative forms of stimulation, giving the individual safe alternatives to chew/bite, and distracting the individual from their pica urges by engaging them in other activities.

Complications

Complications will vary depending on the non-food substance consumed.

Important complications to consider include:

- Nutritional deficiencies (e.g. iron and zinc deficiency from eating clay).

- Anaemia and other physical health issues (due to nutritional deficiencies).

- Gastrointestinal disturbances including constipation or the development of a bezoar (i.e., a mass of undigestible material trapped inside the GI tract, often the stomach).

- Poisoning (e.g. lead poisoning – children’s toys are a common source of lead poisoning).

- Parasitic infection (e.g. a tapeworm resulting from consuming dirt).

- Damage to teeth and gums from eating hard non-food substances such as metal.

Last updated: January 2024

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback