Post-traumatic stress disorder

Notes

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) describes a constellation of symptoms and experiences that an individual develops after exposure to a traumatic event or multiple events

Many people who experience a traumatic event will struggle with negative emotions, thoughts, and unpleasant memories of the event. These symptoms are often transient and ease over time but for some, symptoms will persist and intensify.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) describes a constellation of symptoms and experiences that an individual develops after exposure to a traumatic event or multiple events. These include:

- Re-experiencing the traumatic event (e.g. memories, flashbacks, nightmares).

- Avoiding thoughts and memories: individuals typically try to avoid thoughts and memories of the traumatic event or avoid activities, situations, or people that remind them of the traumatic event.

- Negative changes in mood and thoughts (e.g. amnesia for details of trauma, self-blame, negative self-perception, low mood, losing interest and enjoyment in activities).

- Hyperarousal, hyperreactivity, or hypervigilance (e.g. exaggerated startle response, insomnia, hypervigilance to threat, angry outbursts).

These features of PTSD result in severe impairment of an individual’s functioning and can occur alongside other mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety.

We will explore the features of PTSD in further detail in the diagnosis section below. We have focussed on the diagnosis and treatment of PTSD in adults, however many of the same principles apply in children and adolescents.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of PTSD differs across the world with a peak around 12%.

Studies carried out across the world have found differing prevalence of PTSD, ranging from 1% to 12%. This variation is likely due to the different populations being considered with PTSD occurring more frequently in those living in conflict-affected areas. In these areas there is a higher likelihood of being exposed to a traumatic event. The estimated prevalence of PTSD in the UK is 3-5%.

Aetiology & risk factors

Certain individuals are at risk of developing PTSD, but there are also risk factors associated with the traumatic event itself.

PTSD is thought to occur in genetically pre-disposed individuals who have been exposed to environmental factors (i.e. the traumatic events). Thousands of genetic loci have been associated with PTSD. In addition, neuroimaging studies have shown that PTSD is associated some structural brain changes and altered neurochemicals in the brain (e.g. increased central noradrenaline levels).

Risk factors for PTSD can be divided into:

- Those related to the traumatic event.

- Those unrelated to the traumatic event.

Risk factors related to the traumatic event

These include:

- Likelihood of being exposed to a traumatic event: some people are more likely to be exposed to a traumatic event. This could be due to a specific occupation like those working in war zones (members of the armed forces, charity workers), emergency service workers (ambulance, police, fire brigade) or healthcare professionals (especially in intensive care and A&E). Refugees and asylum seekers from places of high conflict or war are also at increased risk of PTSD.

- Type of traumatic event: studies have noted higher rates of PTSD following rape and physical assault compared to accidents.

- The severity of the incident: the more severe the incident and the greater the threat to life, the higher the chance of PTSD.

- Multiple traumas or previous experience of trauma.

Risk factors unrelated to the traumatic event

These include:

- Female sex

- Younger age

- Low social support

- History of mental health disorder

- Multiple major life stressors

Clinical features & diagnosis

Patients with PTSD have a significant cognitive, affective, and/or behavioral response to the traumatic event.

Both DSM-V and ICD-11 can be used as frameworks to aid the clinical diagnosis of PTSD. They are largely the same, with a few minor differences. Below the diagnosis of PTSD is outlined using DSM-V criteria. Within this criteria, there are different groups termed A-E that cover the typical clinical features that a person may be experiencing.

- Criterion A: Traumatic event

- Criterion B: Intrusive symptoms

- Criterion C: Avoidant symptoms

- Criterion D: Negative cognitions and mood

- Criterion E: Arousal and reactivity changes

Criterion A: Traumatic event

Exposure to trauma; including actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. The person may be exposed to the traumatic event or events in one or more of the following ways:

- Directly experiencing the trauma.

- Witnessing the traumatic events occur to others (in person).

- Learning that the traumatic events occurred to others (close family member or friend).

- Experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to unpleasant details of the traumatic event (for example first responders to a road traffic accident)

NICE Guidelines give further examples of traumatic events that may lead to the development of PTSD and suggest that these are specifically asked about:

- Serious accidents

- Physical and sexual assault

- Abuse (including childhood or domestic abuse)

- Work-related exposure to trauma (including remote exposure)

- Trauma-related to serious health problems or childbirth experiences (e.g. intensive care admission or neonatal death)

- War and conflict

- Torture

Criterion B: Intrusion symptoms or re-experiencing

Intrusion symptoms can be thought of as the individual re-experiencing the traumatic event after it has occurred in one (or more) of the following ways:

- Memories that are recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive.

- Dreams/nightmares that are recurrent and distressing.

- Flashbacks or dissociative reactions in which the individual feels or behaves as though the traumatic event is recurring.

- Psychological distress is in response to things that remind the person of the trauma.

- Physiological reactions in response to things that remind the person of the trauma (for example fight or flight bodily reactions).

Criterion C: Avoidance of reminders

This may refer to avoiding either internal or external reminders:

- Internal reminders: avoidance of distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings closely associated with the traumatic event.

- External reminders: avoidance of people, places, conversations, activities, objects, or situations that remind the individual of the traumatic event.

Criterion D: Negative changes in mood and thoughts

Mood changes are very common in PTSD and usually begin or worsen after the traumatic event (≥2 should be present):

- Amnesia: unable to recall key features of the traumatic event.

- Negative beliefs & expectations about oneself, others, or the world.

- Misattributed or exaggerated blame of oneself or others for causing the trauma.

- Persistent negative emotional state: this may be shame, guilt, low mood, fear, or anger.

- Difficulty experiencing positive emotions.

- Loss of interest in activities.

- Feeling isolated from others.

Criterion E: Hyperarousal, hyperreactivity or hypervigilance

Hyperarousal, hyperreactivity, or hypervigilance, beginning or worsening after the traumatic event (≥ 2 should be present):

- Irritability or aggression (often in response to minor stimuli).

- Reckless or self-destructive behaviour.

- Hypervigilance to perceived threats.

- Exaggerated startle response to stimuli such as loud noises.

- Difficulty concentrating.

- Sleep disturbance: often difficulty falling asleep or broken sleep.

Diagnosis of PTSD

When making a formal diagnosis of PTSD the above symptoms must be present for at least one month and cause the individual significant distress or functional impairment (e.g. social, occupational, or other important aspects of functioning). In addition, the symptoms cannot be better explained by another illness, substance use, or medication.

In addition to the above, the DSM-V asks clinicians to specify whether PTSD occurs alongside any dissociative symptoms:

- Depersonalisation: characterised by the individual feeling of being detached from oneself. They may have experiences of unreality or being an outside observer concerning one’s thoughts, feelings, sensations, body, or actions.

- Derealisation: characterised by the individual feeling detached from their surroundings. They may experience the world around them as unreal, visually distorted, distant, foggy, or dreamlike.

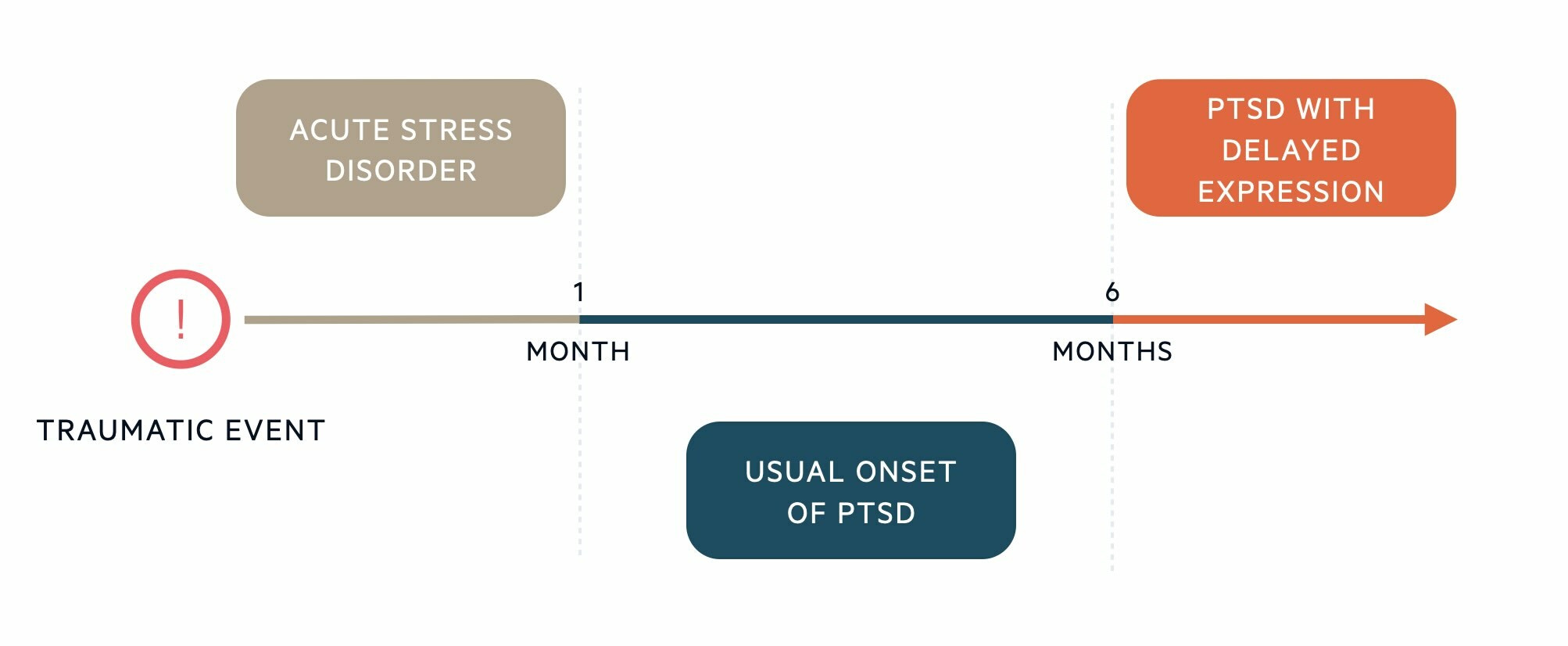

Timeline

The symptoms of PTSD can start immediately after a traumatic event but may not present for a few weeks or months.

The features of PTSD usually start within 6 months of the traumatic event. PTSD cannot be diagnosed in the first month after a traumatic event. In the first month after a traumatic event, a person might be diagnosed with an Acute stress disorder. If the full diagnostic criteria are not met until at least 6 months after the event, then the DSM-V refers to this as PTSD with delayed expression.

Complex PTSD

Complex PTSD is a relatively new diagnosis, set out in ICD-11.

The key additional features that the ICD-11 sets out, which may prompt a diagnosis of complex PTSD include:

- Emotional dysregulation: difficulty regulating emotions, heightened emotional reactions to minor stressors, violent outbursts, self-destructive behaviours, dissociative symptoms when under stress.

- Negative view of oneself: beliefs about oneself as diminished, defeated, or worthless accompanied by feelings of shame, guilt, or failure in relation to the traumatic event.

- Relationship difficulties: difficulty sustaining relationships and feeling close to others.

You may notice that there is some overlap between these features and those described in DSM-V. DSM-V does not include a diagnosis of complex PTSD, but still covers these features in the criterion detailing negative changes in moods and thoughts and their specifier for the presence of dissociative symptoms.

Differential diagnosis

PTSD cannot be diagnosed within the first month of a traumatic event that differentiates it from an acute stress disorder.

- Acute stress disorder: similar symptom profile to PTSD but occurs within 1 month after the traumatic event. PTSD cannot be diagnosed in the first month after a traumatic event.

- Depression: common features include low mood, inability to experience positive emotions, loss of interest/enjoyment in activities, negative beliefs about oneself, irritability, sleep disturbance, and poor concentration.

- Anxiety disorders: including generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and specific phobias. PTSD shares several features with anxiety disorders including; feeling on edge, poor concentration, irritability, and avoidance of situations that trigger anxiety.

- Dissociative disorders: characterised by depersonalisation (feeling detached from oneself) and derealisation (feeling detached from surroundings).

- Psychosis: vivid intrusive flashbacks or memories of the traumatic event may be difficult to distinguish from hallucinations. The key differentiator is that psychosis is characterised by a loss of contact with reality whereas with features of PTSD reality testing remains intact.

Management

PTSD can be treated with talking therapies, medication or a combination.

The two major management strategies in PTSD include talking therapies and pharmacotherapy. Decisions around treatment will be guided by the severity of the presentation and patient preference. Referral to a Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) is usually required for further specialist management of PTSD.

Psychological therapies

Patients with PTSD should be offered cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which focuses on the link between our thoughts, behaviours, and emotions. Challenging negative thoughts and changing unhelpful behaviours can have a positive impact on how a person feels. Patients with PTSD may benefit from a subtype of CBT known as 'trauma-focused'.

The behavioural component of trauma-focused CBT might involve gradually exposing a person to reminders of the traumatic event that they normally avoid. This might be internal reminders (memories, thoughts) or external reminders (people, places, conversations). Avoidance of these reminders only strengthens the anxiety response. By gradually exposing themselves to more stressful reminders and tolerating the anxiety, the fear response should over time reduce.

The cognitive component of trauma-focused CBT might involve challenging negative automatic thoughts or beliefs they might hold about the traumatic event, themselves or the world. For example, challenging thoughts that lead the person to overestimate the ongoing threat or challenging self-blaming thoughts.

Trauma-focused CBT is usually up to 12 sessions on a weekly basis.

Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR)

EMDR uses eye movements to help the brain process traumatic memories. The person is asked to recall the traumatic event and recall thoughts and feelings associated with the event. Whilst doing this, the person will be asked to perform eye movements or receive another sort of ‘bilateral stimulation’ such as hand tapping. EMDR has been shown to lower the intensity of the emotions a person experiences around a traumatic memory. Up to 12 sessions are usually offered, although more complex presentations are likely to require longer treatment.

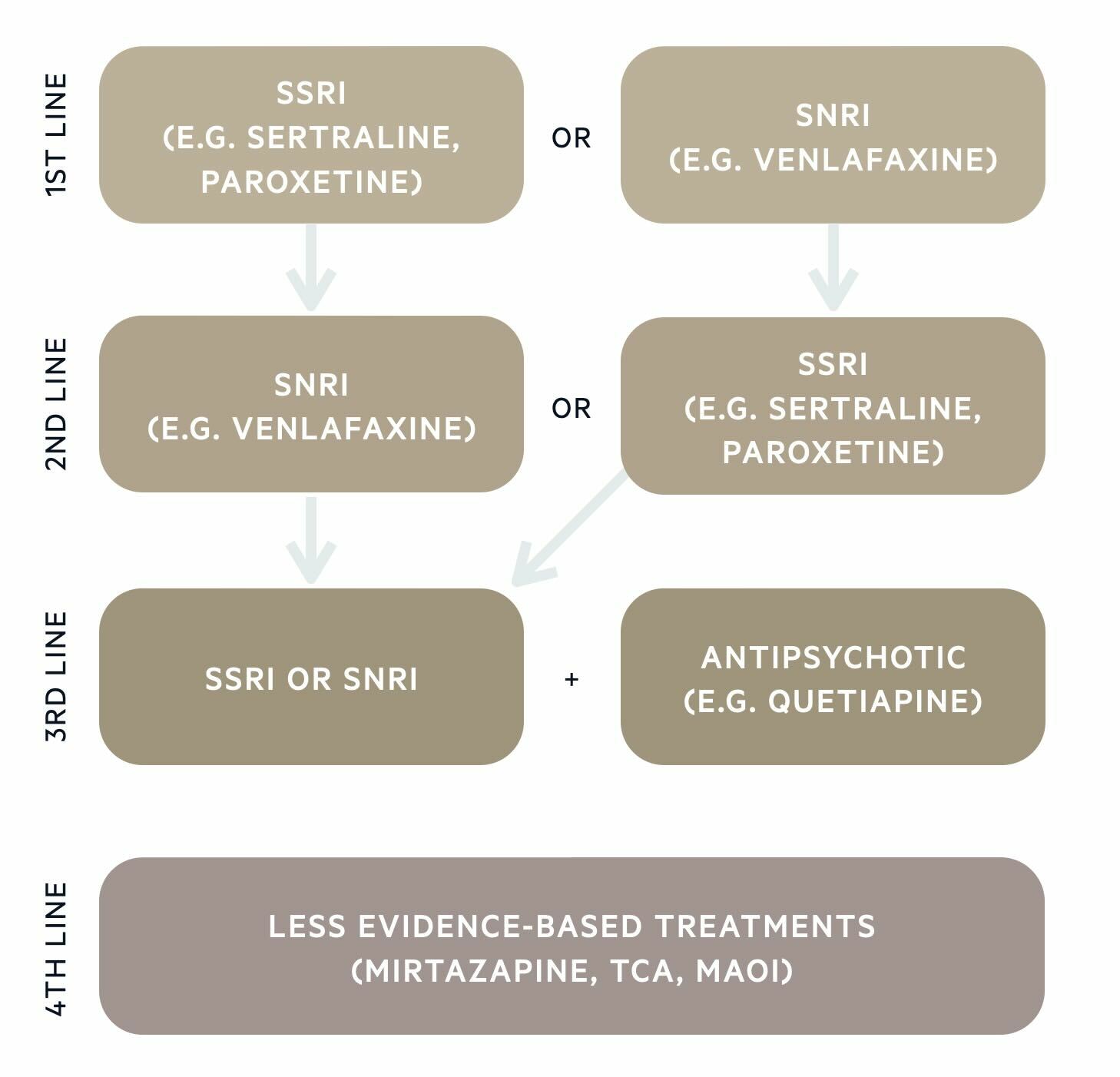

Pharmacological therapies

Antidepressants are commonly prescribed for PTSD. These medications are effective for mood and anxiety-related symptoms. Antipsychotics are effective for intrusion symptoms but not avoidance or hyperarousal symptoms.

Three classes of drugs are typically used in PTSD:

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- Serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Anti-psychotics (dopamine antagonists)

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants are less commonly used as the evidence base is weaker, but these could be trialled 4th line if there has been an incomplete response to previous drug classes.

Sleep is often an issue for those with PTSD, so in addition to advising about sleep hygiene, it may be appropriate to prescribe a short-term course of a sleeping tablet (e.g. zopiclone).

Other management considerations

As with other mental health disorders, the following points also form an important part of any management plan and should be considered:

- Explain & educate: written information on PTSD and treatment options (psychotherapy and medication) is often helpful. It may be hard for the patient to retain information given verbally.

- Involve the support network: the family may benefit from practical or emotional support and education about PTSD.

- Assess and manage risk: the individual may pose a risk of harm to themselves or others and may be at risk of harm from others. Those deemed to be high risk may require more intensive support and monitoring (home treatment team, inpatient admission).

- Active monitoring: the management plan may need to change if the individual’s presentation or risks change.

- Screen for co-morbidities: assess for and provide appropriate treatment for commonly co-occurring mental health disorders including other anxiety disorders and depression.

- Screen for substance or alcohol misuse: the patient may benefit from additional input from drug and alcohol services.

Last updated: January 2024

References:

-

DSM-V

-

ICD-11

-

NICE guideline [NG116] - Post-traumatic stress disorder

-

McManus, S. et al (2016). Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey: Survey of Mental health and Wellbeing, England, 2014

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback