Breast cancer

Notes

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy affecting women in the UK.

It may be diagnosed during screening or patients may present with a breast (or axillary) lump. Pain, skin and nipple changes may also prompt presentation. On occasion, patients will present with symptoms of metastatic spread.

Management is holistic, with input from members of the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) and centred around the individual patient's thoughts and wishes.

Breast cancer can occur in anyone. It can affect women, trans-women, trans-men, men and non-binary individuals. In men, it is less common and is not within the top 20 cancers affecting men in the UK. There is evidence that the risk is increased in transgender women taking gender-affirming hormonal treatments.

Epidemiology

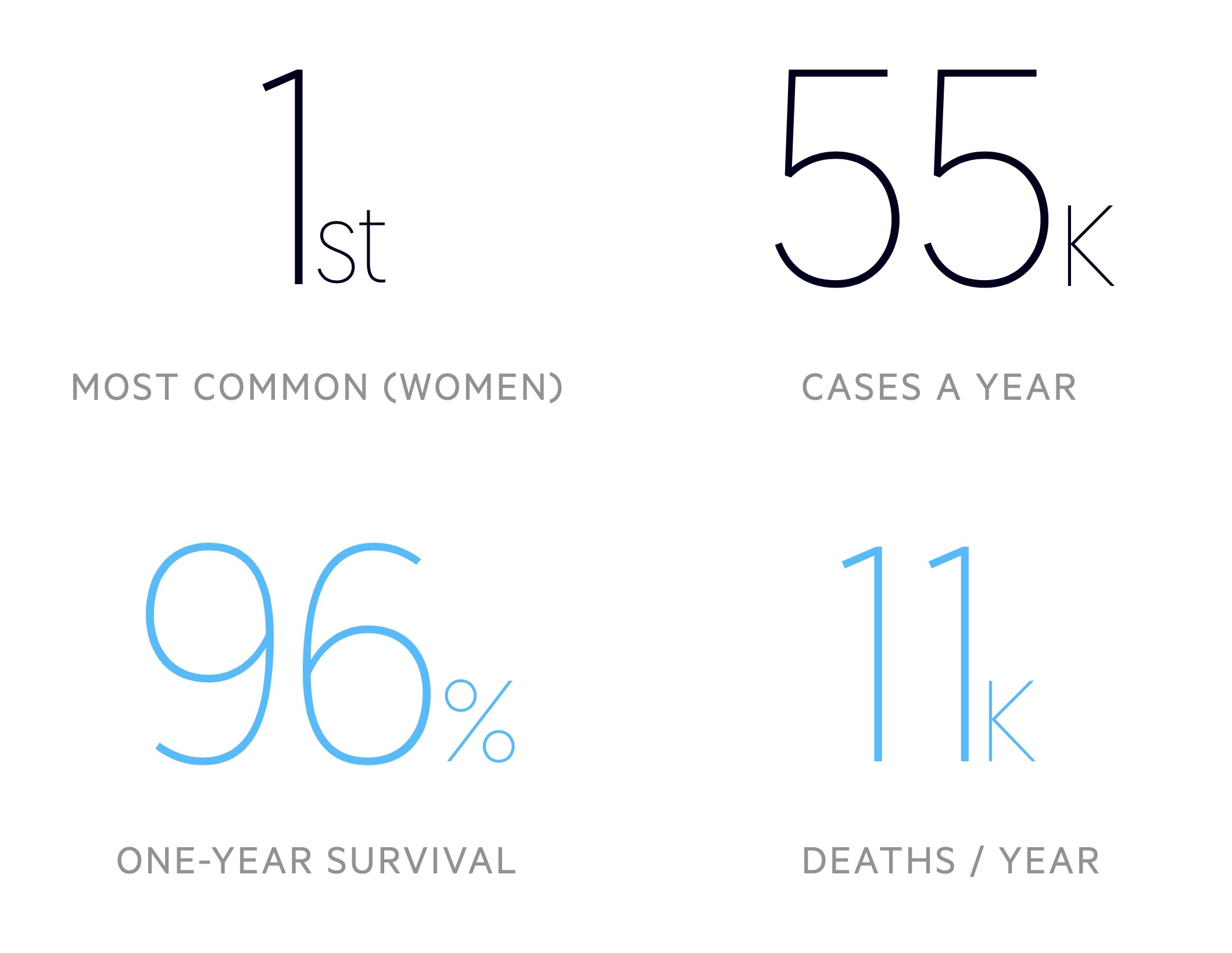

There are around 55,000 cases of breast cancer in the UK each year.

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women - around 1 in 8 will develop it in their lifetime. Incidence is greatest in those aged 90+. According to Cancer Research UK, it is more common in white women when compared to black and asian women.

It is far less common in men with around 390 cases each year, which represents around 0.7% of the total caseload. As described above, the risk of breast cancer is increased in trans-women on gender-affirming hormonal treatment (a single cohort study showed a 46-fold increase compared to cisgender men, though the absolute risk remains lower than women, see here for more information).

Risk factors

A number of risk factors are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.

- Female gender

- Age

- Family history

- Personal history of breast cancer

- Genetic predispositions (e.g. BRCA 1, BRCA 2)

- Early menarche and late menopause

- Nulliparity

- Increased age of first pregnancy

- Multiparity (risk increased in period after birth, then protective later in life)

- Combined oral contraceptive (still debated, effect likely minimal if present)

- Hormone replacement therapy

- White ethnicity

- Exposure to radiation

BRCA

There are a number of hereditary syndromes that may predispose to breast cancer.

Here we will focus on the breast cancer type 1 and 2 susceptibility genes (BRCA 1 and 2):

- BRCA 1: Caused by a mutation on chromosome 17 that predisposes patients to breast cancer amongst other malignancies. The lifetime risk of breast cancer is approximately 65-80% (compared to a baseline of around 12%) whilst the risk of ovarian cancer is 40-45% (compared to a baseline of around 1.3%).

- BRCA 2: Caused by a mutation on chromosome 13 that predisposes patients to breast cancer amongst other malignancies. The lifetime risk of breast cancer is approximately 45-70% whilst the risk of ovarian cancer is 11-25%.

The incidence of BRCA mutations is higher in certain populations. Approximately 2.5% of the Ashkenazi Jewish population is affected. Populations from historically distinct geographic locations show different variants. Research is ongoing to determine the various rates of mutations in different ethnic groups.

BRCA mutations also increase the risk of breast cancer in men. BRCA 2 appears to be more of a risk factor with approximately 8% of men affected developing breast cancer, compared to 1% with BRCA 1 (baseline - 0.1%).

These mutations (primarily BRCA 2) are also known to increase the risk of a number of other malignancies. This includes peritoneal, endometrial, fallopian, pancreatic and prostate cancer.

Pathology

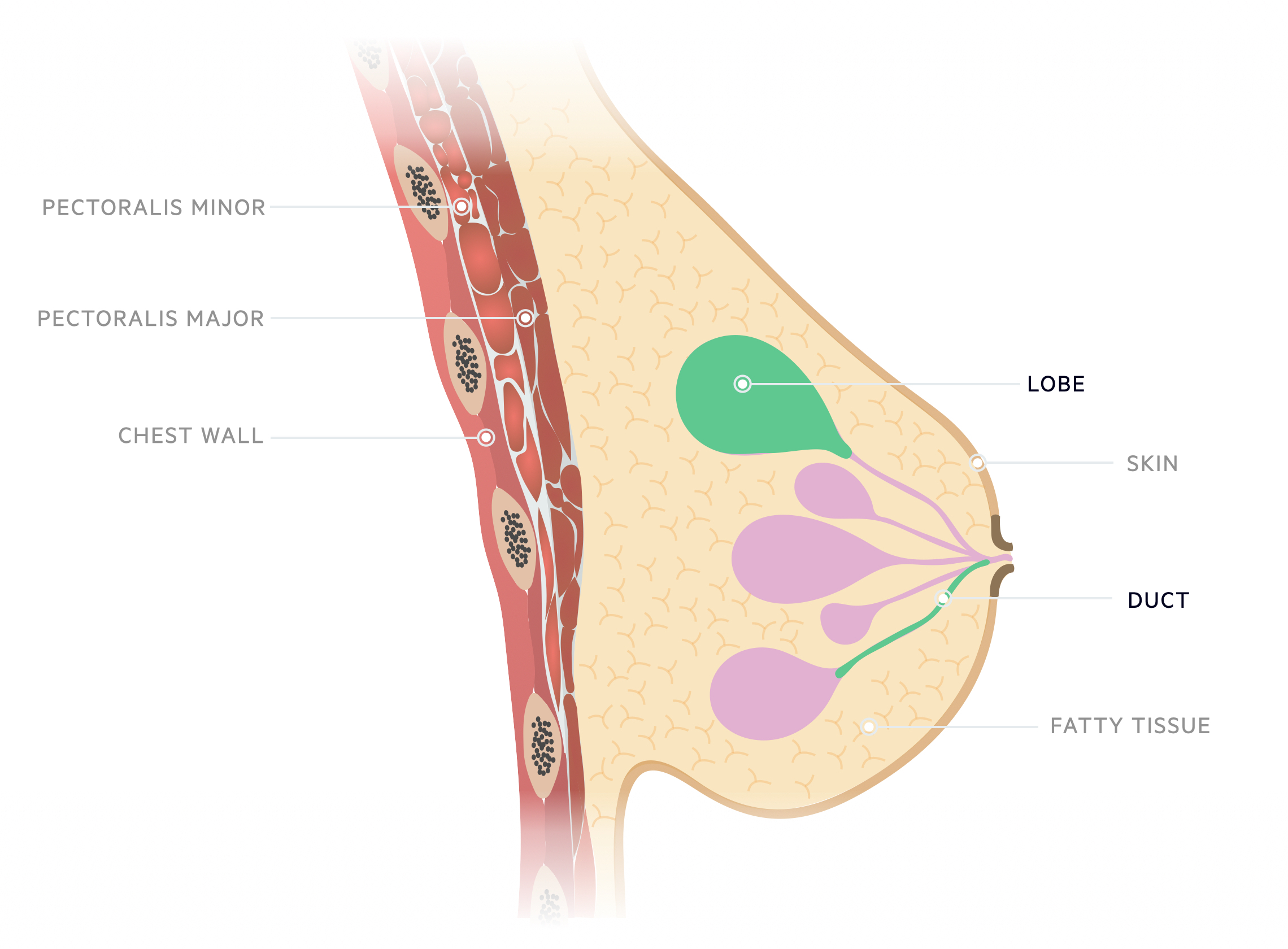

The majority of breast malignancies are carcinomas, these are divided into either ductal or lobular.

An understanding of basic breast anatomy is key. Aside from origin, cancers may be described as either in situ (not penetrating the basement membrane) or invasive.

Ductal

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

DCIS refers to a heterogeneous group of non-invasive lesions. They may progress to invasive malignancy.

DCIS lesions may be categorised as high, intermediate and low grade. Comedo DCIS is a high-grade type that has an increased risk of invasion.

Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC)

IDC composes around 70-80% of invasive breast cancer - it is the most common invasive breast cancer. It may be graded based upon how well or poorly differentiated the cells are. Grade 1 refers to well, grade 2 - moderately and grade 3 - poorly differentiated tumours.

Lobular

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)

LCIS is a relatively uncommon finding that may be referred to as lobular neoplasia. It tends to be found incidentally on biopsy. Though its presence is indicative that a woman is at greater risk of invasive breast cancer, the direct relationship is unclear.

NB - The remainder of the management in this note will refer to invasive cancer, DCIS or both. Management of LCIS is not covered.

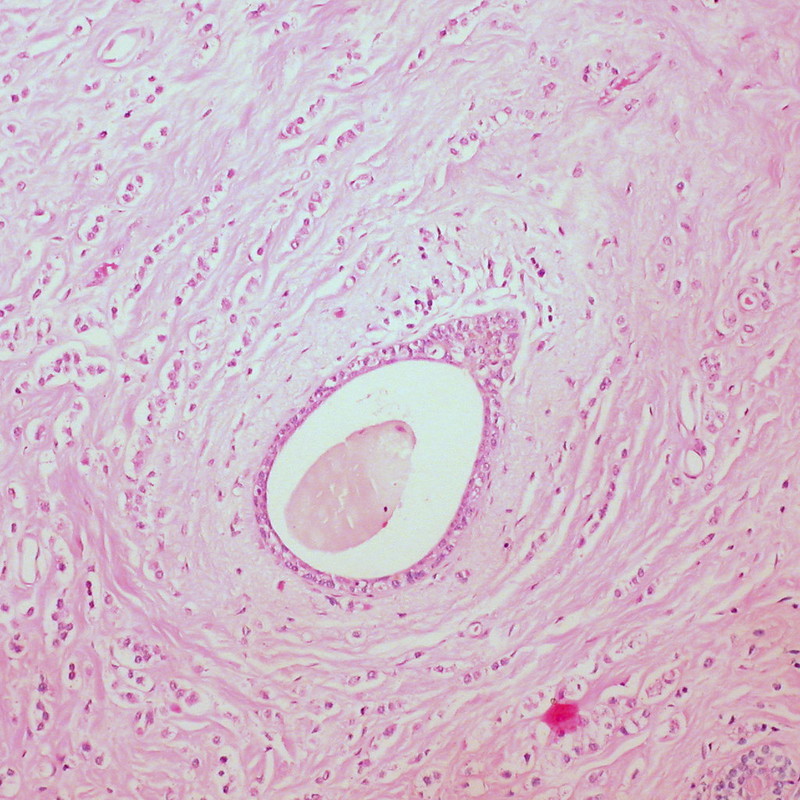

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC)

ILC is the second most common invasive breast cancer composing 5-10% of cases. There is growing evidence of a relationship with post-menopausal hormone therapy. The vast majority are oestrogen receptor-positive.

Molecular subtypes

Invasive breast cancer can be categorised into one of four molecular subtypes based upon gene expression (receptor status of oestrogen receptors and progesterone receptors, HER2 and Ki-67).

- Luminal A

- Luminal B

- Basal

- HER2

Screening

The NHS runs a screening programme to detect breast cancer.

In England, breast cancer screening runs from the ages of 50 to 71. In some areas, an increased age range of 47 to 73 is being trialled.

The programme invites women, as well as trans-men (if they have not had chest reconstruction or have breast tissue). Trans-women are also invited to screening as gender-affirming hormone replacement is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Of note, for the referral to be automated the individual needs to be registered as female else they need to ask their GP for a referral. For more information see here.

Screening involves a mammogram conducted by a female mammographer. The images are then reviewed by a consultant radiologist with several possible results:

- Satisfactory: no radiological evidence of breast cancer, approximately 96% will have a normal result

- Abnormal: abnormality detected, further investigations needed. Around a quarter with an abnormal result will subsequently be found to have breast cancer.

- Unclear: results or imaging unclear or inadequate. Further investigations required.

Additional screening exists for those with family history and may involve genetic testing and imaging at a younger age.

Breast implants: Implants can pose a challenge for mammography. Radiographers should be appropriately trained in the use of the Eklund technique - a way of obtaining images to optimise breast cancer detection in those with implants. See here for more information.

Clinical features

Breast cancer often presents with a breast or axillary lump.

Breast cancer may be asymptomatic, particularly in the early stages of the disease, hence a screening programme exists to improve time to diagnosis. Patients may also present after noticing a breast lump or one of a number of other symptoms.

Breast and axillary lumps may be picked up by patients following routine self-examination or because it causes pain or discomfort. They are often hard, irregular and fixed to surrounding structures.

- Breast and/or axillary lump:

- Often irregular

- Typically hard/firm

- May be fixed to skin or muscle

- Breast pain

- Breast skin:

- Change to normal appearance

- Skin tethering

- Oedema

- Peau d’orange

- Nipples:

- Inversion

- Discharge, especially if bloody

- Dilated veins

Features may also reflect metastatic spread. The bone (bone pain), liver (malaise, jaundice), lungs (shortness of breath, cough) and brain (confusion, seizures) are most commonly affected.

Referral

NICE (NG 12, Jan 2021 update) have set out criteria to guide referral for patients with symptoms suggestive of breast cancer.

Patients should be referred on a two-week wait suspected cancer pathway if:

- 30 and over with an unexplained breast lump with or without pain or

- 50 and over with any of the following symptoms in one nipple only:

- Discharge

- Retraction

- Other changes of concern

NICE also recommend clinicians consider a two-week wait suspected cancer pathway for people:

- With skin changes that suggest breast cancer or

- Aged 30 and over with an unexplained lump in the axilla

Consider non-urgent referral in people aged under 30 with an unexplained breast lump with or without pain.

Local services may have their own urgent referral guidelines, additional reasons for which a clinician may urgently refer include 'women with unilateral non-cyclical breast pain persisting beyond one menstrual cycle'. Clinicians judgement should be used - if concerns exist they should discuss with the local specialist service.

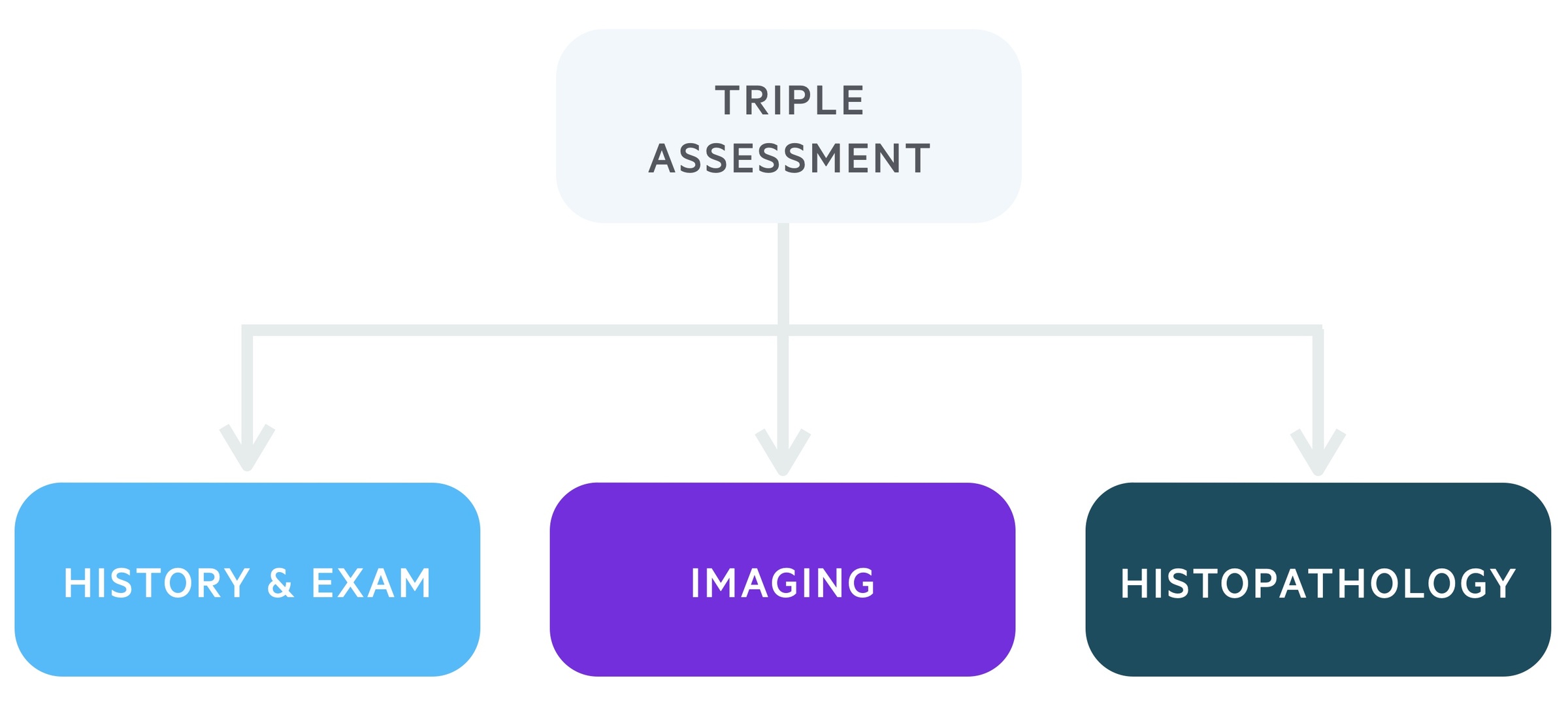

Triple assessment

Following referral for suspected breast cancer, patients will be reviewed in the ‘one-stop breast clinic’.

The one-stop breast clinic incorporates a triple assessment in one appointment. It requires localities to have access to appropriate specialists and diagnostic equipment but offers patients a convenient and efficient service.

The majority of patients can be reassured that they do not have evidence of breast cancer following a single visit. Some may need to await further tests (e.g. core biopsy results) whilst others may be given a likely diagnosis.

1. Clinical history and examination

Each patient referred to a two-week wait one-stop clinic will be reviewed by a specialist. This will involve a detailed history including family history. Following this, the patient will be carefully examined.

2. Imaging

This will depend in part on the history and examination and the patient's age. Clinics are set up to conduct both breast USS and mammograms.

- Mammogram: A mammogram utilises x-rays to image breast tissue. Findings suggestive of cancer include soft tissue masses and microcalcifications.

- USS: Breast USS is the modality of choice in women under the age of 40. It is also used in older women, particularly when mammography and clinical findings do not align. High-resolution scanners meeting NHSBSP standards are used.

3. Histopathology

Depending on the initial two steps, a tissue/cellular sample may be taken. This is usually in the form of a fine-needle aspiration (FNA), in which provisional results may be obtained the same-day or core biopsy, which often also provides provisional same-day results, but may have to wait up to a few days.

Histological specimen: Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast

Image courtesy of Ed Uthman

Further investigations

Further investigations are needed to help stage disease and plan management.

Bloods

- FBC

- Renal function

- LFT

- Bone profile

Imaging

- CXR

- Breast tomosynthesis: An additional investigation used infrequently utilising mammography to produce a 3-D representation of the breast.

- MRI breast: May be used as an adjunct, normally under the guidance of the Breast MDT. It is useful in certain settings, such as patients with high risk family history/genetics and those with occult primary tumours. NICE also recommends that it may be used in invasive cancer to guide treatment, assess tumour size if breast-conserving surgery is planned in patients with invasive lobular cancer, or if breast density prevents accurate assessment via other modalities.

- CT chest, abdomen and pelvis: In patients with suspected advanced disease can be used to identify visceral metastasis.

- CT brain: In symptomatic patients with suspected neurological spread.

- Contrast-enhanced liver USS: May be used in those with suspected liver metastasis.

- Bone scan: May be used to identify spread to bones.

- PET/CT: Not routine, use guided by the Breast MDT. There are a number of complex indications, but in general, it is used in advanced disseminated disease to guide management or where the results of other imaging modalities are not clear.

Receptor testing

Oestrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) status should be measured. The hormones oestrogen and progesterone are known to impact the growth of breast cancers and the receptor status helps to identify patients who may benefit from endocrine therapy.

Human epidermal growth receptor 2 (HER2) status is also routinely measured, overexpression is seen in around 20% of patients. It indicates which patients will benefit from Herceptin (trastuzumab), a monoclonal antibody that blocks the HER2 pathway.

Triple-positive breast cancers refer to those that are positive for ER, PR and HER2. At the other end of the spectrum are triple-negative tumours.

Assessment of axilla

In patients with early invasive breast cancer, USS may be used to assess axillary lymph nodes. When abnormal lymph nodes are found, they may be sampled with ultrasound-guided needle sampling (FNA).

Genetic testing

Consideration should be made based on patients age, medical history and family history as to whether genetic testing is indicated.

In patients under 50 with triple-negative breast cancer (ER-negative, PR-negative, no excess HER2), testing for BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 should be offered.

Management principles

Management should be centred around each individual’s needs and wishes and guided by a specialist MDT.

Input from multiple specialities including breast surgeons, plastic surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, histopathologists, specialist nurses and palliative care may be needed. Management should be guided by a Breast cancer MDT.

Patients may require psychological support and where needed specialist psychiatric services. Involvement in relevant clinical trials should be offered and discussed where appropriate.

As a general rule management can be split into early-stage, locally advanced and advanced metastatic disease. The majority of the below management discusses early-stage and locally advanced disease. Advanced metastatic disease is discussed in the final management chapter.

Surgery

In early and locally-advanced breast cancer, excision of the primary tumour plays a key part in the management of breast cancer.

A number of operative options are available, and choice is guided by patient wishes, clinical history, tumour size, staging and genetics amongst other considerations.

Resection of the primary tumour

- Breast conservation: Many patients will be appropriate for breast conservation surgery. This most commonly takes the form of wide local excision (WLE). Consideration should be predominantly made based on the size and location of the tumour, with consideration of the desired aesthetic result. Whole breast radiotherapy is indicated in most cases to reduce the risk of local recurrence. Margins must be checked, and where necessary re-excision/mastectomy discussed.

- Mastectomy: Indicated in a number of scenarios. Mastectomy may be preferred if there is an unfavourable tumour to breast ratio, where radiotherapy is contraindicated, multifocal tumours and some recurrent tumours. For breast reconstruction see below.

Lymph node assessment

Unnecessary lymph node clearance can lead to significant morbidity and as such a targeted approach is needed.

Further assessment of lymph nodes in the axilla may need to be completed at the time of surgery. In patients with invasive breast cancer (and some DCIS) and negative pre-operative studies of the axilla (i.e. no evidence on axillary USS or negative ultrasound-guided needle biopsy). This most commonly takes the form of a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB).

Breast reconstruction

Following mastectomy, some patients may wish to have reconstructive surgery. This may be performed immediately at the time of mastectomy or delayed as a separate procedure.

Depending on the type of reconstruction, the surgery may be staged over two or more procedures. There are many considerations that should be discussed with the patient as to whether to opt for immediate or delayed reconstruction. Immediate reconstruction (and possible complications) may impact the timing of further treatment with chemo- and/or radio- therapy.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy often plays the role of a key adjunct, reducing recurrence following breast conserving surgery.

Radiotherapy is not without its risks and the dose transmitted to neighbouring structures and organs (heart and lungs) should be minimised. NICE do state ‘there is no increase in serious late effects’ (e.g. congestive cardiac failure, myocardial infarction or secondary cancer) when radiotherapy is given.

Radiotherapy has been shown to reduce the risk of local recurrence from 50 per 1000 at 5 years to 10 per 1000. Overall 10-year survival however is unchanged. Local complications of radiotherapy include soreness, fibrosis of breast tissue and change in skin tone.

After breast conservation surgery

As a general rule, radiotherapy is advised following breast conserving surgery. Whole breast radiotherapy is used in those with invasive breast cancer (with clear margins). It may also be discussed in those with DCIS.

In certain groups, partial breast radiotherapy and even omitting radiotherapy may be considered. This tends to be those with a very low risk of recurrence taking adjuvant endocrine therapy for five years. See NICE guidelines for further details.

After mastectomy

Radiotherapy may also be used following a mastectomy in certain situations:

- Offer radiotherapy if node-positive (macrometastases) invasive breast cancer or involved resection margins.

- Consider in those with node-negative T3/4 disease.

Regional nodes

Adjuvant radiotherapy to regional nodes may be offered to certain patients. It is not used where nodes have been shown to be negative or to the axilla after axillary clearance.

Radiotherapy may be used to target the supraclavicular fossa (+/- internal mammary chain) in those with invasive breast cancer and 4 or more involved axillary lymph nodes or 1-3 lymph nodes with poor prognostic factors (with a suitable performance status).

Chemotherapy & biologics

Chemotherapy and biologics may be used to further reduce risk of recurrence and improve survival.

As with other treatment modalities, the decision to offer chemotherapy is based upon stage, age, co-morbidities and patient wishes. Below we discuss some of the settings where chemotherapy may be used.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Chemotherapy may be given prior to surgical management. The decision to give neoadjuvant therapy is guided by the MDT with patient input.

It may be used to reduce tumour size pre-operatively. It is also used in patients with inflammatory breast cancer.

Adjuvant chemotherapy

A cohort of patients will be considered for adjuvant chemotherapy. These tend to be regimens containing a taxane and an anthracycline.

An example regime, FEC, contains:

- Fluorouracil

- Epirubicin

- Cyclophosphamide

Biologics

Trastuzumab (Herceptin): In those with HER2 positive, T1c or greater invasive disease, trastuzumab may be offered. It is a monoclonal antibody that targets HER2 receptors.

It may cause significant cardiac-based adverse effects and cardiac function should be assessed prior to and during use. It may harm a developing foetus and pregnancy must be avoided during and seven months post-treatment.

Endocrine therapy

Endocrine therapies are typically used as an adjunct to other treatments to reduce risk of recurrence.

Adjuvant endocrine therapy

Patients with ER/PR positive disease are offered adjuvant endocrine therapy. In women or those with ovaries, treatment choice depends on ovarian function. There are two main options:

- Tamoxifen: a Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator (SERM) used first-line in men and pre-menopausal women. Also offered to post-menopausal women at low risk of disease recurrence or if aromatase inhibitors are contra-indicated. Risks of tamoxifen include blood clots, endometrial cancer and reduced bone mass in premenopausal women (may be protective in postmenopausal). Women should not become pregnant whilst on tamoxifen or for 2 months post-treatment.

- Aromatase inhibitors (e.g. anastrozole): Used first-line in post-menopausal women who are at high or medium risk of disease recurrence. It inhibits the peripheral conversion of androgens to oestrogens. Alone they are not effective in premenopausal women where oestrogens are primarily synthesised by the ovaries. Side effects include menopausal symptoms, osteoporosis and musculoskeletal pain.

Endocrine therapy tends to be commenced after any adjuvant chemotherapy. A standard course lasts 5-years. Extended therapy beyond 5-years may be considered - the benefits and risks should be discussed with the patient.

At times neo-adjuvant endocrine therapy may be given. This tends to be in the context of a clinical trial.

Ovarian function suppression

Ovarian function suppression may be considered in premenopausal women with ER +ve disease. Use is guided by the MDT and patient wishes:

- GnRH analogue (e.g. goserelin)

- Laparoscopic oophorectomy

Metastatic breast cancer

In advanced metastatic breast cancer, treatment aims to prolong survival and improve quality of life.

Receptor status, ER, PR and HER2, are key (as they are with localised disease) and should be used to guide therapies. Endocrine treatment with tamoxifen or anastrozole (see above) and targeted therapy with Herceptin may be used where receptor status is positive.

A number of chemotherapy regimens are available, and the side-effects must be weighed and explained in the context of the potential for improved survival. Medications such as denosumab and bisphosphonates may be used to prevent lytic bone lesions and reduce bone pain and fracture.

Prognosis

The prognosis is dependent on stage and grade of disease, tumour characteristics and patient co-morbidities.

Overall in England for women diagnosed with breast cancer:

- One-year survival - 95.8%

- Five-year survival - 85%

Prognosis worsens in advanced age with 5-year survival in women over 80 around 70%. Survival is best in those aged 60-69, this is thought to be due to screening and tumour characteristics. Those diagnosed with late stage disease have just a 26% survival rate at 5-years.

Further reading

Check out the links below for more information on breast cancer.

- Breast cancer Now: A charity working to offer information, support and funding for research

- Cancer Research UK: Full of facts and information for patients and clinicians alike

- NICE NG 12: Suspected cancer: recognition and referral

- NICE NG 101: Early and locally advanced breast cancer: diagnosis and management

- NICE CG 81: Advanced breast cancer: diagnosis and treatment

- NICE CG 164: Familial breast cancer: classification, care and managing breast cancer and related risks in people with a family history of breast cancer

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback