Acute cholangitis

Notes

Overview

Acute cholangitis refers to infection of the biliary tree characteristically resulting in pain, jaundice and fevers.

Acute cholangitis almost always occurs due to bacterial infection secondary to biliary obstruction. The terms acute and ascending cholangitis can be used interchangeably.

Biliary obstruction is often secondary to choledocholithiasis (gallstones in the biliary tree) or biliary strictures (both benign and malignant). Management involves antibiotics, supportive care and urgent decompression of the obstructed biliary system.

Epidemiology

Acute cholangitis is a relatively uncommon condition.

The exact incidence is unknown. The median presenting age is 50-60, affecting men and women equally. There appears to be greater incidence in Caucasians, Hispanics and Native Americans - following the distribution of gallstones.

It occurs following ERCP in around 0.5 - 3%. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis is seen in Southeast Asian populations.

Aetiology

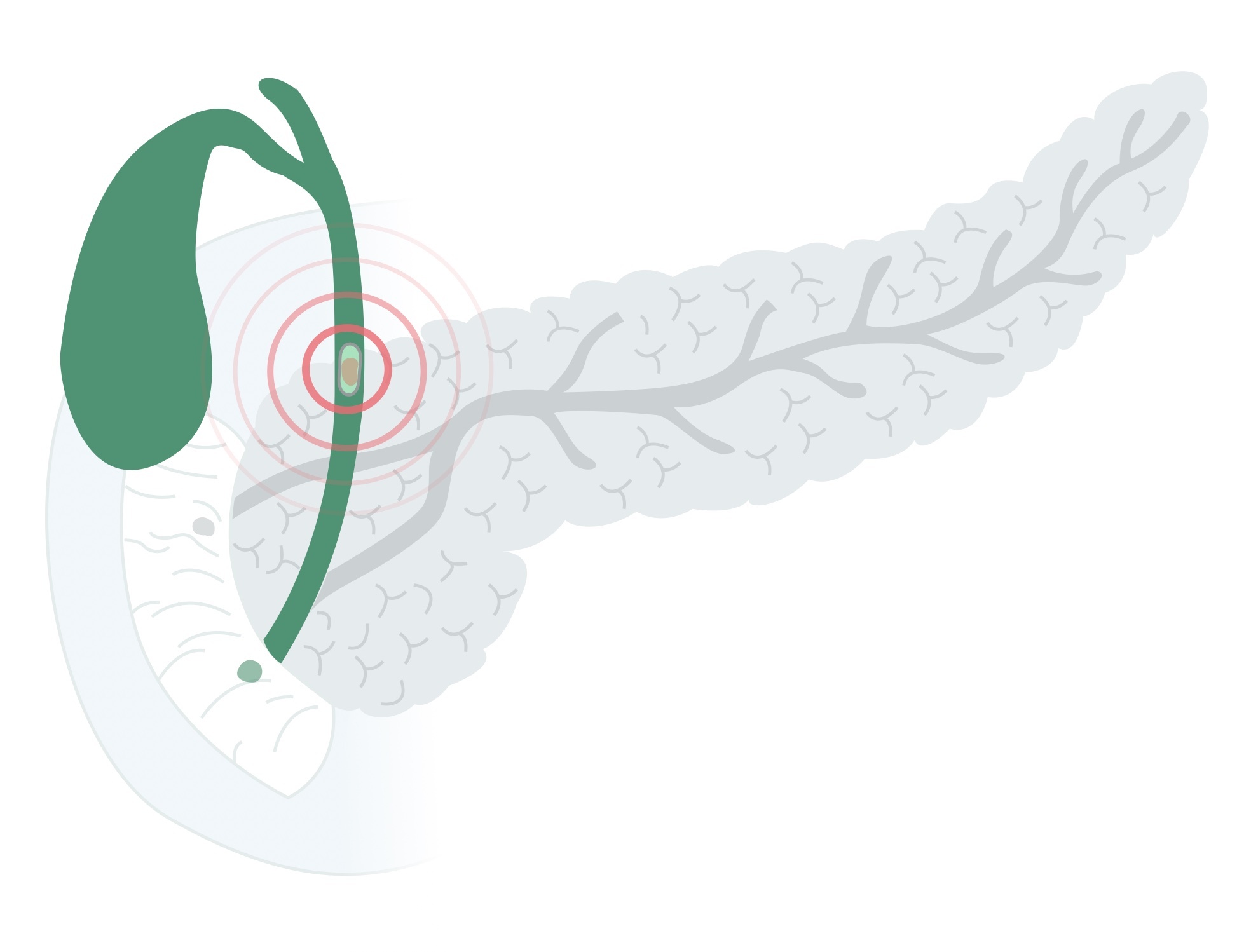

Choledocholithiasis, stones in the bile duct, are the most common cause of acute cholangitis.

Choledocholithiasis

Choledocholithiasis refers to gallstones within the bile ducts. It occurs in around 10-20% of people with cholelithiasis (gallstones). It should be noted that not all patients with choledocholithiasis develop cholangitis, and such stones may be asymptomatic.

Acute cholangitis occurs due to impaired drainage and bacterial overgrowth. It is the most common cause of ascending cholangitis, implicated in around 80% of cases.

Benign stricture

Benign strictures, leading to obstruction, may occur in the biliary tree for numerous reasons:

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Iatrogenic injury (e.g. during cholecystectomy)

- Radio / chemo-therapy

- Idiopathic

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a chronic, progressive condition associated with ulcerative colitis. It is characterised by inflammation and stricturing of bile ducts. Although the strictures are typically benign, patients are at increased risk of many cancers including cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Malignant stricture

Malignant biliary strictures may lead to acute cholangitis. Malignancies include cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic cancer and gallbladder cancer.

Other

- Post-ERCP (normally related to inadequate drainage)

- Blocked biliary stent

- Extrinsic compression

- Blood clots

- Parasites (e.g. Ascaris lumbricoides)

Clinical features

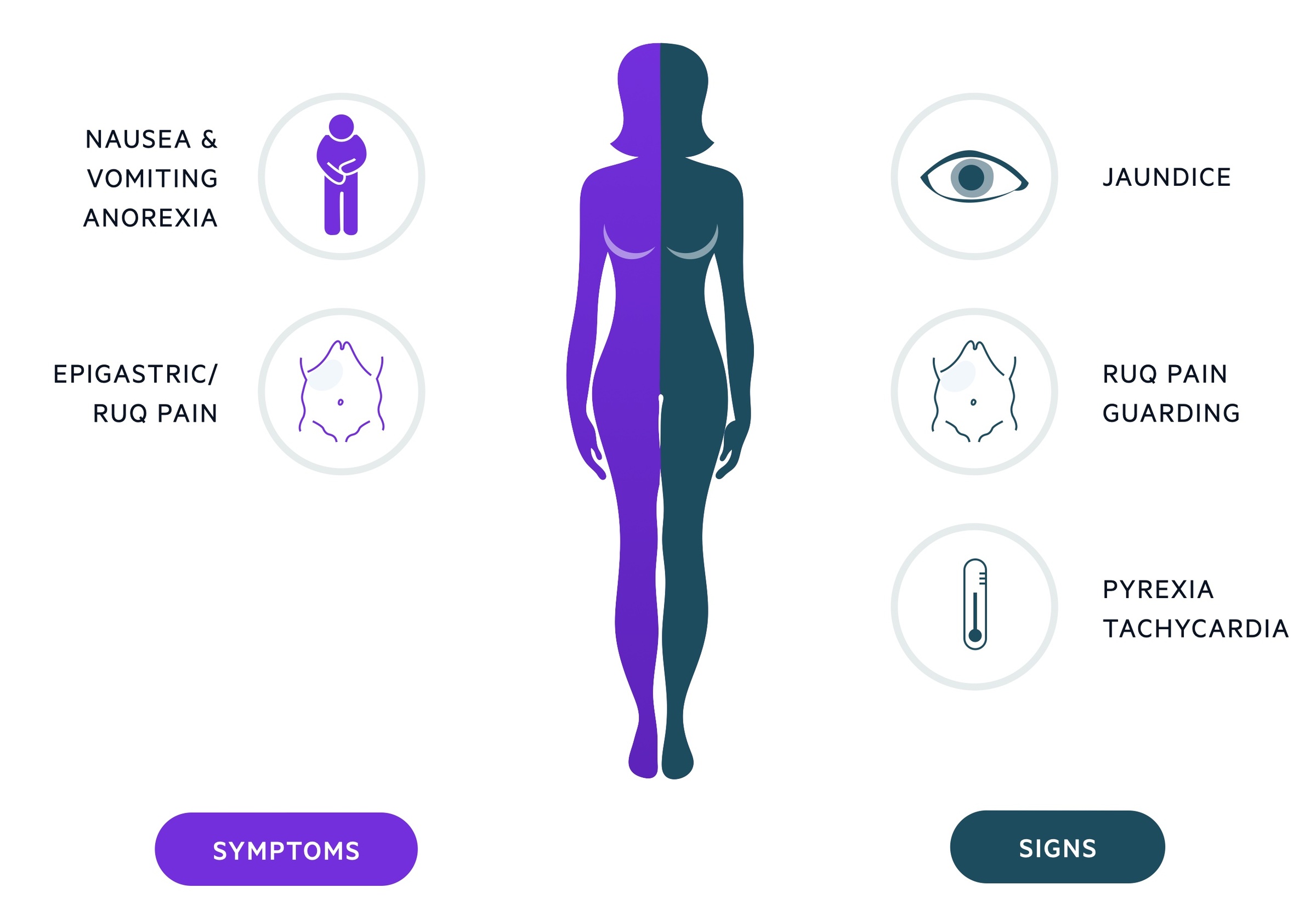

Ascending cholangitis often presents with upper abdominal pain, jaundice and fevers.

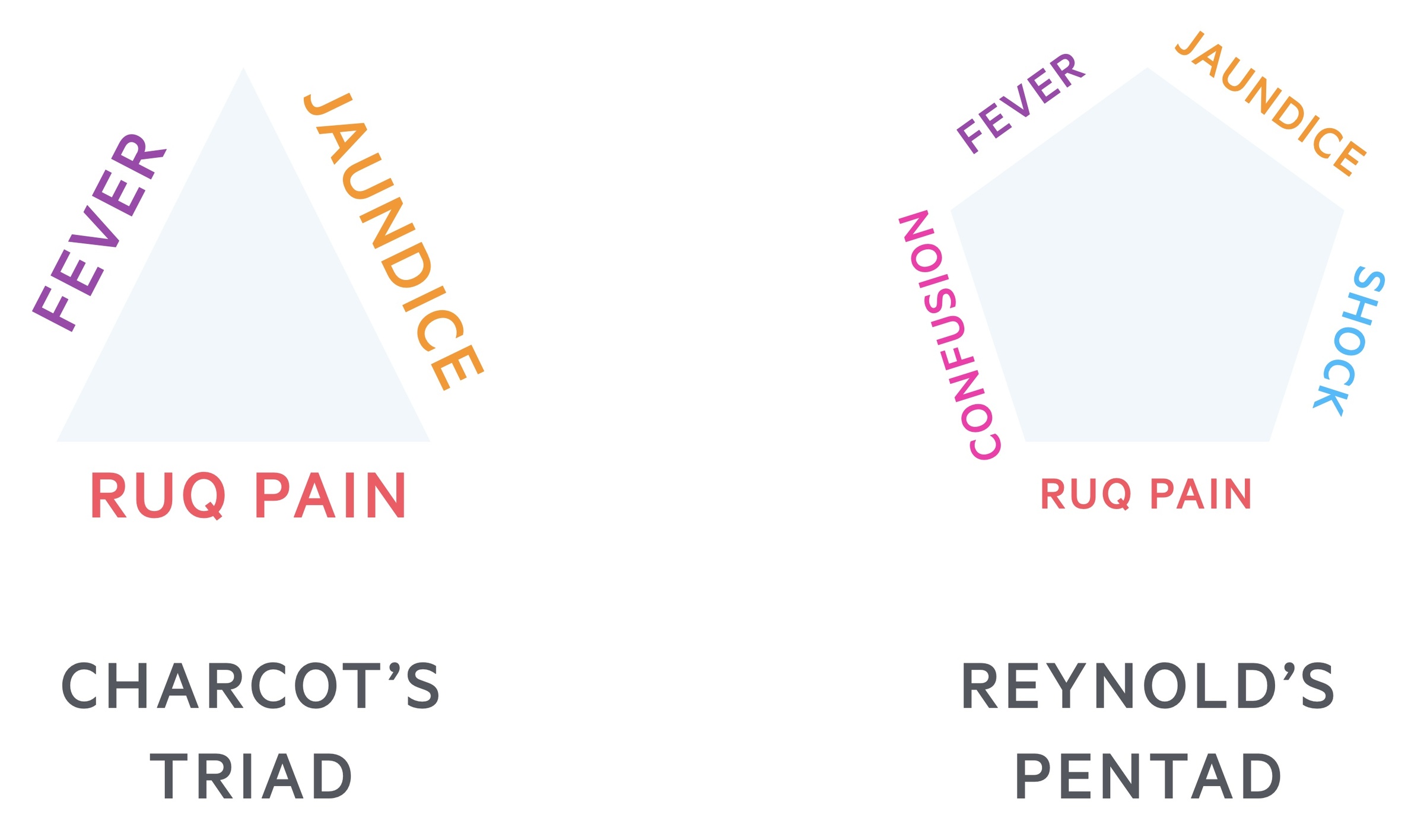

Ascending cholangitis was first described by Charcot as a life-threatening condition. We now know it may present with a wide spectrum of symptoms though fever, jaundice (may be sub-clinical) and pain are common. Two sets of symptoms are often described:

- Charcot's triad: RUQ pain, fever, jaundice

- Reynolds pentad: RUQ pain, fever, jaundice, shock, confusion

Not all features may be present, Charcot's triad is seen in around 50-70% of cases. Shock and confusion are only seen in the most serious cases with systemic sepsis. Jaundice is often best seen in the sclera, it may be less clinically apparent in those with darker skin tones. If there is any suspicion send for urgent LFTs and make the assessment by reviewing the bilirubin.

Symptoms

- RUQ / epigastric pain

- Fevers

- Malaise

- Nausea/vomiting

Signs

- RUQ / epigastric tenderness

- Pyrexia

- Jaundice

- Hypotension (severe cases)

- Confusion (severe cases)

Investigations

Acute cholangitis is most commonly investigated with USS, CT abdomen/pelvis and MRCP.

Patients typically presented with upper abdominal pain, tenderness, jaundice and fever. Blood tests reveal elevated inflammatory markers and an obstructive picture (raised bilirubin and ALP, though transaminases may also be elevated) on liver function tests.

Bedside

- Observations

- BM

- Urine dip

- Pregnancy test (any woman of child-bearing age)

Bloods

- Full blood count

- Urea & electrolytes

- CRP

- Liver function tests

- Amylase

Imaging

Ultrasound: allows assessment of the gallbladder for gallstones and assessment of the CBD

Computed tomography: good visualisation of the biliary tree, including the distal portion, used where USS inconclusive, to evaluate for abnormal lesions/tumours or where other diagnoses are suspected.

MRCP: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography offers excellent visualisation of the biliary tree. Often used where CT/USS are inconclusive.

Special

ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography involves the endoscopic intubation of the ampulla of Vater. It offers excellent views of the biliary tree whilst allowing therapeutic intervention such as drainage. ERCP is now generally a therapeutic rather than diagnostic intervention.

Management

Patients with an infected, obstructed biliary system require urgent drainage.

Medical care

Initial management should follow an ABC approach in those who are acutely unwell. The sepsis 6 protocol should be implemented when indicated. Key components of management include:

- Antibiotics: IV Augmentin or Tazocin would be standard initial agents. A stat dose of an aminoglycoside (e.g. Gentamicin) may also be given. Antibiotics may be adjusted to reflect culture results as they come in.

- Fluids: Intravenous fluids should be commenced in most patients, both resuscitation and maintenance fluids are required.

- Analgesia: Should be tailored to the patient's needs, age and co-morbidities. An example regimen would include regular codeine and paracetamol with oramorph as required for breakthrough pain.

Biliary drainage

Drainage of the infected biliary system is key to effective management. It is now achieved utilising non-operative techniques (except in very rare cases). There are two main options:

- ERCP: Typically first line and conducted by the gastroenterologists, it relies on the passage of an endoscope into the duodenum and intubation of the ampulla of Vater. A dye may then be injected which when combined with fluoroscopy allows visualisation of the biliary tree. It can be used to retrieve stones, perform a sphincterotomy and place a biliary stent to relieve the obstructed system. Cytology and biopsy samples may also be taken if relevant. Complications include acute pancreatitis, duodenal perforation and gastrointestinal bleeding.

- PTC: Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography may be used if ERCP fails, is unavailable or inappropriate. Conducted by interventional radiologists it involves percutaneous puncture to access the biliary tree through the liver. PTC allows for drainage of the biliary system, stone retrieval and stent placement. The major risk is haemobilia (bleeding into the biliary system).

Ongoing care

Further management depends on the underlying aetiology. Elective cholecystectomy is indicated in those with gallstones after a period of recovery.

Those with strictures need the cause identified (if not already) and may require further surgery/endoscopic management. Malignancies are managed via appropriate MDTs.

Last updated: May 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback