Brain tumours

Notes

Overview

Brain tumour is a generic and broad term for a wide range of pathologies.

A brain tumour is a broad term for an intracranial tumour, or mass, affecting structures such as the meninges, brain, glands, neurovascular structures and/or bone. Other words that may be used to describe an intracranial tumour include a mass, growth, space-occupying lesion (SOL) or central nervous system (CNS) lesion. The term 'brain tumour' itself is very generic and should generally be avoided as the management and prognostication for each type differ considerably. Where possible, it is important to use precise terminology.

The clinical presentation, management, and prognostication of a brain tumour will depend on various factors that include:

- Location

- Size

- Histology

- Surgical resection margins

- Genetics

- Many others

The various types of brain tumours are classified according to the WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System (CNS). This classification is part of a very complex nomenclature, which includes genetic and molecular profiles as part of an integrated histological diagnosis. Therefore, a brain tumour as a term covers anything from an olfactory groove meningioma to an Oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant, and 1p/19q-codeleted tumour.

As this no doubt highlights, whilst a full review of every single tumour type is well beyond the scope of undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula, an understanding of common tumour types and their management is important.

A lot of steps will overlap despite different tumour types because investigations, such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Head with Contrast form the initial basis of investigation for nearly all types of tumours. Furthermore, management steps such as referring to a multidisciplinary team will largely be similar. There are subtle differences such as the use of steroids (dexamethasone) and this should be appreciated in the relevant context. These core principles form the basis of the management of nearly all tumour types with some variations.

Classification

The World Health Organisation (WHO) provides a classification system for tumours of the central nervous system.

Basic oncological terminology

Broadly, a tumour can be defined as benign or malignant:

- Benign: a term that refers to pre-cancer or non-cancer (i.e. some benign tumours have malignant potential). Stay in the primary site without distant spread. Tend to grow slowly and have distinct borders.

- Malignant: a term that refers to cancer. The hallmarks of cancer include things such as increased proliferative, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, invasion and distant spread (i.e. metastasis).

Malignant tumours may be further classified based on their grading and staging:

- Grade: this refers to how abnormal the cancer appears under the microscope. Typically well, moderately or poorly differentiated (i.e. how much they look like the original cell type).

- Stage: this refers to how far cancer has grown and spread. It is usually classified according to 'TNM' staging, which refers to T - tumour size, N - nodal spread, M - distant metastasis.

Classifications of tumours will also incorporate other factors such as:

- Location (e.g. cerebellum)

- Tumour type (e.g. glioma, oligodendroglioma)

- Genetic/molecular diagnosis (e.g. IDH-mutant)

CNS tumour classification

Tumours of the CNS are now classified according to the WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System (CNS) following recommendations of cIMPACT-NOW. This is a more modern classification system that takes into account many different factors about the tumour to provide a more precise histopathological diagnosis.

This classification is complex, but the broad groups include:

- Gliomas, glioneuronal tumours, and neuronal tumours: this includes tumours such as astrocytoma, glioblastoma, oligodendroglioma, and ependymal. Gliomas are a broad group of tumours that arise from glial cells which are the non-neural cells of the central nervous system.

- Mesenchymal, non-meningothelial tumours: refers to tumours arising from supporting connective tissue of the central nervous system

- Cranial and paraspinal nerve tumours (e.g. Neurofibroma or Paraganglioma)

- Tumours of the sellar region (e.g. pituitary adenoma)

- Hematolymphoid tumours (e.g. CNS lymphoma)

- Choroid plexus tumours (e.g. Choroid plexus papilloma)

- Metastases to the CNS: the spread of malignant tissue from another primary site to a location within the central nervous system

- Melanocytic tumours: these are tumours derived from melanocytes

- Embryonal tumours (e.g. Medulloblastoma)

- Germ cell tumours (e.g. teratoma)

- Pineal tumours (e.g. Pineoblastoma)

- Meningiomas: this refers to tumours arising from the meningeal lining

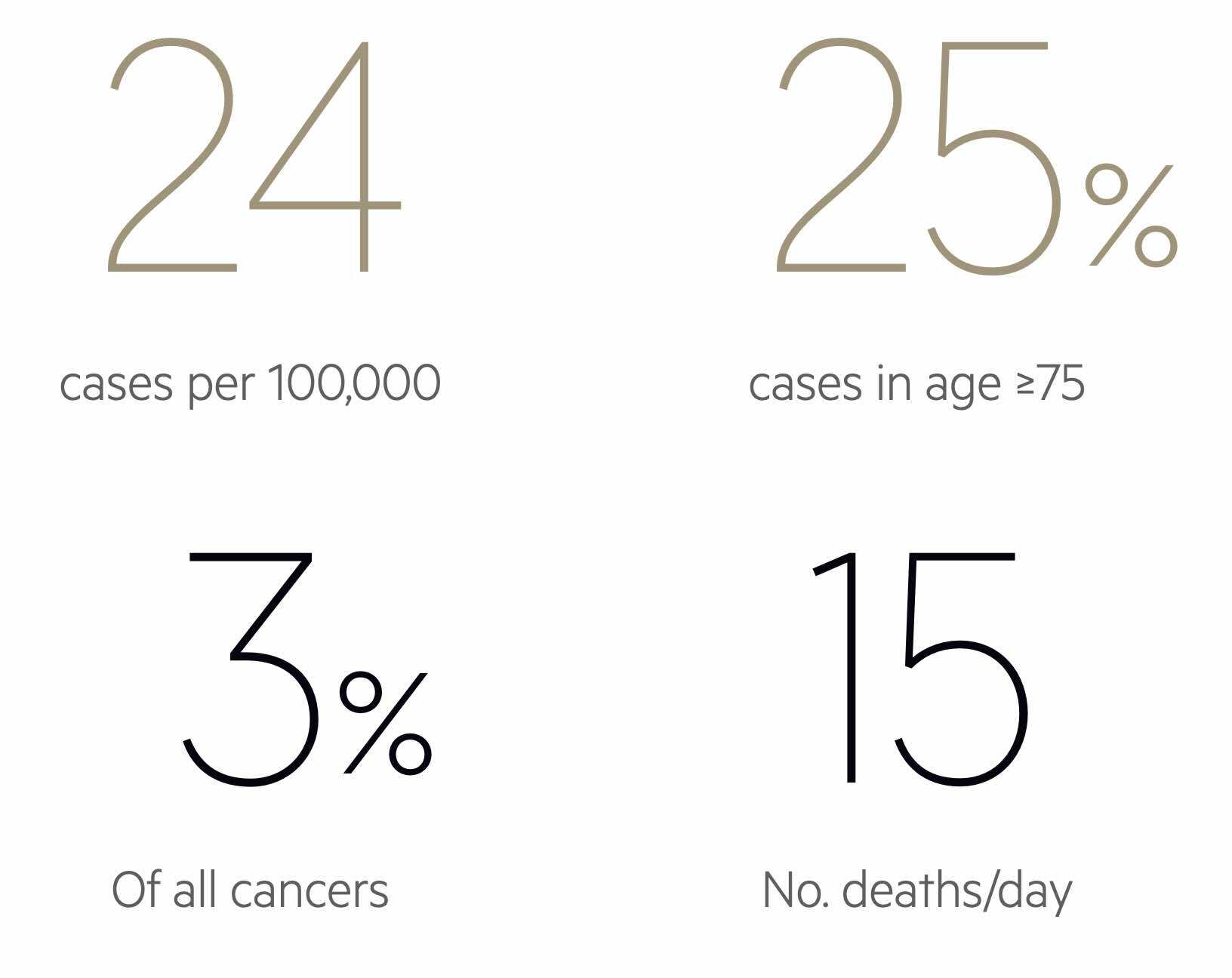

Epidemiology

Brain tumours can occur at any age with the most common in adults being meningioma and glioma.

The incidence and prevalence of brain tumour types largely depend on patient demographics such as age. In children, primary tumours of the CNS are the most common type of solid tumour and the second most common cancer overall behind haematological malignancies. In adults, meningiomas and gliomas account for approximately two-thirds of primary CNS tumours. Glioblastoma is considered the most common primary CNS tumour in adults.

As people get older (i.e. beyond 30-40 years old), metastatic brain tumours become much more common and account for 50% of cases.

Clinical features

Common clinical features associated with brain tumours include features of raised intracranial pressure, focal neurological deficits, and seizures.

The skull is a closed vault and any lesion whether it is blood, infection or a tumour can exert a mass effect. Lesions which exert mass effect can only present in a handful of ways. Therefore brain tumour presentations can be clustered together into features of raised intracranial pressure (ICP), focal neurological deficits, and seizures.

At other times, brain tumours may be associated with no clinical features and merely detected incidentally on a scan (e.g. MRI brain) completed for another reason.

Raised intracranial pressure

The classic feature of raised ICP is a headache. This may be the presenting feature in up to 50% of brain tumours. However, it makes up a very small percentage of the overall causes of headaches.

Other features associated with raised ICP include:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Swollen optic discs

- Reduced conscious level

The headache of raised ICP is described as dull, constant, and often bilateral. The headache tends to worsen over time and may be exacerbated by positional changes (e.g. bending over) or acts that increase intrathoracic pressure (e.g. coughing, sneezing). Headaches may also occur at night, sometimes waking the patient, and be associated with nausea and/or vomiting.

A classical feature often reported with brain tumours is an early morning headache but this is not always the case and the headache phenotype can mimic other headache types such as tension or migraine.

Focal neurological deficits

Neurological signs and symptoms typically depend on the location of the tumour and the neurological area involved/compressed. Common examples of focal neurological deficits include:

- Weakness

- Sensory changes

- Language defects (e.g. aphasia)

- Visual defects (i.e. due to compression along the visual cortex)

Seizures

Seizures associated with a brain tumour may be focal ( localised to a network of neurons in one hemisphere of the brain) or generalised (affecting both hemispheres of the brain and associated neuronal networks).

Seizures affect up to 80% of patients with primary brain tumours and 20% of those with metastatic brain tumours. Focal seizures are more common and these depend on the location of the tumour. Seizures are typically repetitive and are stereotyped (i.e. they commonly recur with the same pattern).

Investigations

Neuroimaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the principal investigation for brain tumours.

Brain tumours are detected by neuroimaging. This can be with CT or MRI.

MRI with contrast is considered the optimal modality for the assessment of brain tumours. CT is usually restricted for emergency evaluation (e.g. new-onset status epilepticus, suspected bleed, sudden loss of consciousness) as it can be completed and reported rapidly, or in patients who have a contraindication to MRI.

Further investigations depend on the suspected type of tumour, for example:

- CT chest, abdomen, pelvis: looking for a primary tumour in suspected brain tumour metastasis

- Lumbar puncture: atypical appearance (to exclude other causes like infection) or suspected primary CNS lymphoma

Tumour types

The WHO classification describes over 100 different types of brain tumours.

Among the WHO classification, some brain tumours are exceedingly rare, whereas others make up a large proportion. Due to the vast number of tumour types, it is impossible, and not beneficial, to discuss all the individual brain tumours. Instead, in this overview note we will focus on the most important type of brain tumours for undergraduate students to comprehend, which will include:

- Gliomas

- Meningiomas

- Lymphomas

- Pituitary tumours

- Brain metastasis

Gliomas

A glioma is a broad term for a brain tumour that arises from glial cells founds in the central nervous system such as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and ependymal cells.

Gliomas describe tumours derived from the glial cells founds in the central nervous system such as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and ependymal cells. These tumours are considered intrinsic tumours as they are derived from within the brain parenchyma. Accordingly, tumours derived from these are labelled astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and ependymomas.

Glioblastoma is the most common malignant brain tumour. It was previously known as a glioblastoma multiforme or grade IV astrocytoma. It has an incidence of 3 in 100,000 with a median age of 64 years old at the time of diagnosis. It is more common in men compared to women (1.6:1).

Clinical Presentation

History is usually non-specific but should involve screening for the main clinical features including headache, nausea/vomiting, visual changes, focal neurological deficits and any seizures. The clinical examination may demonstrate signs in keeping with the location of the tumour or a syndrome. Always suspect it as a differential in a patient with new-onset weakness, slurred speech or falls.

Investigations

- Computed tomography (CT Head): often done in the first instance if the presentation is acute. Should generally avoid contrast as in some units it can delay patients receiving contrast with MRI

- MRI Head with Contrast (gadolinium): multiple sequences are needed to fully characterise a lesion (e.g. T1/T2, DWI/ADC, FLAIR). These give greater anatomical detail and shows the extent of oedema

- CT Thorax Abdomen Pelvis (CT TAP): this is known as a ‘staging CT’, which may be considered if the diagnosis is in doubt following an MRI head. CT TAP checks for primary lesions if a brain metastasis is suspected and guided by the neuro-oncology MDT.

NOTE: More detailed imaging such MR Spectroscopy, functional MRI and/or tractography can be performed to delineate functionally important neuroanatomical tracts (e.g. corticospinal tract).

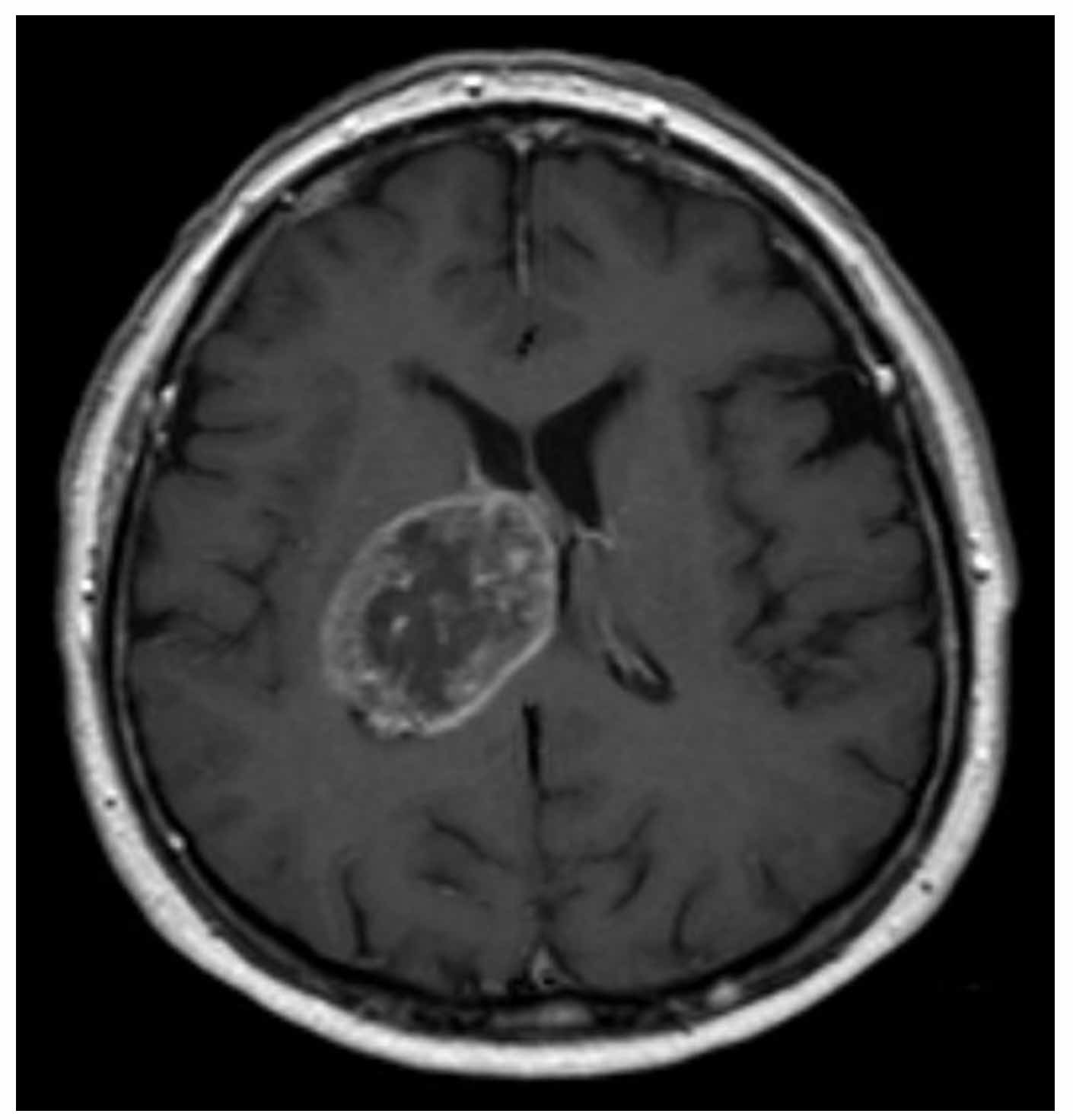

Glioblastoma - MRT T1 axial with contrast

Courtesy of Hellerhoff. Wikimedia Commons.

Management

Management is multifactorial and requires MDT input. It is uncommon to operate on a tumour immediately as several factors such as current clinical status, co-morbid status, and performance status (eg. ECOG) need to be considered.

We can broadly divide the management into acute and longterm:

- Acute

- Referral: neurosurgical team on-call (web-based or telephone referral) and neurosurgical MDT

- Medications: steroids for vasogenic oedema (e.g. dexamethasone), proton pump inhibitors (gastric protection) and anti-seizure medication (e.g. levetiracetam)

- If obtunded: consider the use of hypertonic saline (2.7 or 3%). More effective than mannitol at reducing ICP.

- Long-term

- Surgery: usually a biopsy to obtain histology before further chemotherapy and radiotherapy or a craniotomy to resect the tumour. A biopsy to confirm the diagnosis is offered if gross total resection is not possible for any reason (e.g. multifocal disease, deep-seated lesion like the brainstem, co-morbidities, poor functional status). Both procedures enable a formal histological diagnosis

- Chemoradiotherapy: given depending on the histology. A variety of regimens may be used and guided by the oncologists.

A craniotomy is a surgical procedure that involves the removal of part of the bone from the skull to expose the brain. It may be done awake (i.e. patient woken up intra-operatively to monitor neurological deficits in real-time), with neuro-monitoring (if lesion close to important structures), or with special immunofluorescent agents (to highlight tumour margins). A gross total resection of the brain tumour is associated with a better outcome.

Prognosis

The prognosis for glioblastoma is poor and the average survival time is 12-18 months with only 25% surviving more than a year. A mere 1 in 20 (5%) survive more than 5 years. Interestingly, some molecular markers seen in glioblastoma correlate with prognosis (e.g. isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) gene mutations). IDH-wild type or ‘negative’ means no mutation and poor prognosis whereas IDH-mutant has a good prognosis.

Meningiomas

Meningiomas are the most common primary intracranial tumour.

Meningiomas are tumours considered to originate from the arachnoid cap cells in the meninges. They are not from within the brain parenchyma itself.

Meningiomas are the most common intracranial tumour, which means a tumour within the skull vault but not from the brain parenchyma itself. The incidence is 5 in 100,000 and with rates higher in women compared to men. Meningiomas are often found incidentally due to the increasing availability of imaging modalities (e.g. CT and MRI head scans). The overall prevalence of meningiomas increases with age.

Clinical features

Patients with meningiomas may have clinical features similar to all brain tumours including headache, nausea, vomiting, visual field defects, focal neurological deficits and seizures. However, many meningiomas are completely asymptomatic.

Patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) have a genetic predisposition to developing meningiomas. Up to 50% of patients with NF2 will have meningiomas and often multiple. Other features of NF2 include vestibular schwannoma, neuropathies and even meningiomas affecting the optic nerve. Cutaneous manifestations are seen in 70% but the classic neurofibromas seen in neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) only occur occasionally.

Investigations and management

Investigation and management steps are similar to gliomas. Management is generally conservative for incidental lesions and patients can be followed up with surveillance imaging. Lesions are monitored to see if there is any growth or change. Typically, the majority of meningiomas grow <1 cm3/year. Surgical management is offered if there are neurological symptoms and to prevent further neurological deterioration. MDT discussion is required before offering a procedure. Dexamethasone is considered if there is vasogenic oedema but is not always required.

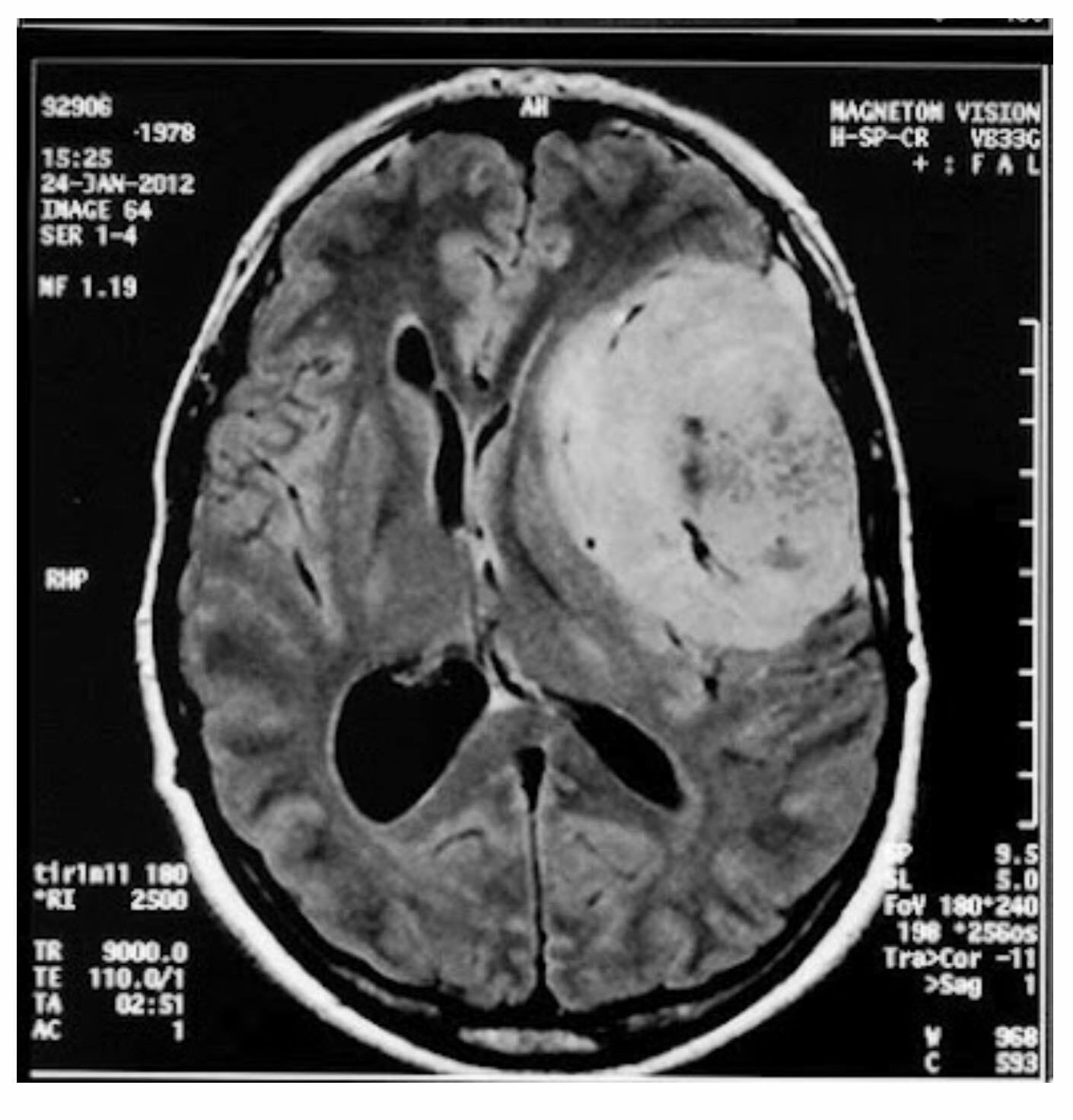

Meningioma on MRI - mass formation of the left frontotemporal region

Grading

Meningiomas can be graded into 1, 2, and 3:

- Grade 1: Benign meningioma

- Grade 2: Refer to specific morphology subtypes of meningioma

- Grade 3: Malignant meningioma (local invasive, distant metastasis rare)

Overall, surveillance imaging schedules, surgical intervention and use of adjuvant radiotherapy depends on the grade of meningioma (among other factors), which correlates to a risk of recurrence. A typical surveillance schedule with an MRI of the brain for a grade 1 meningioma might be at 3-6 months after initial scan, then annually for 3-5 years, then 2-3 yearly thereafter as long as there is no significant change.

Prognosis

The prognosis is generaly favourable as the majority of meningiomas are benign. The overall 5-year survival rate is over 87%. However, this drops to 42% with malignant meningiomas.

Lymphomas

Primary CNS lymphoma is a rare type of brain tumour.

Primary CNS lymphoma is a rare type of brain tumour and can affect both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. The typical age group affected are those > 50 years old at the time of diagnosis and it is more common in males. There are several lymphoma variants with the predominant histological variant tending to be diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Clinical features

Clinical features are largely similar to those mentioned before but it is worth noting that some patients may have a history of being immunocompromised (e.g. due to immunosuppressive medications, infections such as HIV). Additional symptoms may include systemic features such as fever, night sweats and unintentional weight loss (‘B symptoms’).

Investigations and management

The investigations are similar to other brain tumours and require MRI Head with Contrast. Further work-up includes a whole range of laboratory tests similar to any patient with a suspected haematological malignancy. A CT CAP is also obtained to look for widespread disease. A lumbar puncture may be required in the absence of an obvious central lesion (e.g. spinal involvement or leptomeningeal involvement)

Surgical resection is not possible and the mainstay of surgical management is biopsy alone followed by a chemotherapy and radiotherapy regimen. Surgical resection does not alter prognosis. Lymphomas are exquisitely steroid responsive. On initial imaging diffuse lymphoma has several differentials and can be confused for multifocal glioblastoma. Steroids can cause the tumour to shrink. It is important to avoid steroids, if possible, before a confirmed diagnosis is made due the profound effect of steroids on lymphoma cells.

Prognosis

Prognosis is unfavourable and without treatment is usually 1 to 3 months after diagnosis. Lymphoma does respond well to therapy but relapse is common. There are various models that can be used to determine prognosis based on the current best-studied prognostic markers (e.g. age, performance status).

Pituitary tumours

Pituitary tumours are generally benign and commonly adenomas.

The pituitary gland is divided into anterior and posterior. The anterior pituitary gland produces adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), growth hormone (GH) and prolactin (PRL). The posterior pituitary produces oxytocin and antidiuretic hormone (ADH).

Pituitary tumours are generally benign and commonly adenomas that arise from the anterior pituitary. Adenomas are divided into microadenomas and macroadenomas:

- Microadenoma: < 1cm in diameter

- Macroadenoma: > 1cm in diameter

These pituitary adenomas can be further defined as 'functioning' or 'non-functioning':

- Functioning: lead to increased secretion of the hormone produced by the affected cell type

- Non-functioning: does not increase secretion of the hormone produced by the affected cell type and may even lead reduced hormone production

Pituitary adenomas may arise from any cell type within the anterior pituitary and are named accordingly:

- Gonadotroph adenomas: commonly non-functioning

- Thyrotroph adenomas: either non-functioning or lead to hyperthyroidism from excess release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- Corticotroph adenomas: cause 'Cushing's disease' due to excess secretion of ACTH

- Lactotroph adenomas: cause hyperprolactinemia, which can cause hypogonadism

- Somatotroph adenomas: increased secretion of growth hormone leads to acromegaly

Other tumours involving, or around the anatomical area, of the pituitary gland, include primary carcinomas, pituicytomas and metastasis amongst others. Of note, a pictuicytoma is a rare tumour arising from cells of the posterior pituitary gland.

Clinical presentation

The clinical features of a pituitary adenoma can be broadly divided into two major problems:

- Features secondary to mass effect

- Features secondary to excess hormone secretion

Mass effect

A common mass effect of a pituitary tumour is a headache. The quality of the headache is usually non-specific and features of raised intracranial pressure may be present if the tumour is very large or compressing the third ventricle.

Visual field defects are very common due to the close proximity of the pituitary gland to the optic chiasm. Bitemporal hemianopia is a classic visual field defect caused by compression of the crossing nasal retina fibres at the level of the optic chiasm. There is a loss of vision in both temporal fields (the outer half of the visual field). Importantly, the onset of this visual field defect is usually so gradual that patients do not immediately seek ophthalmic assessment and may even go unnoticed for years. Other visual problems that can arise include diplopia due to the extension of a pituitary adenoma to compress the oculomotor nerve.

Excess hormone secretion

Non-functional tumours can be incidental and usually present later with mass effects. Alternatively, functioning tumours can present with a constellation of symptoms that depends on the excess hormone secreted. Some of these are well established clinical syndromes such as acromegaly or Cushing's disease.

The typical clinical presentations by hormone are as follows:

- Prolactinomas (prolactin-secreting): amenorrhoea, galactorrhoea in females and impotence, decreased libido and galactorrhoea (rare) in men

- Cushing’s disease (ACTH-secreting tumour): weight gain, amenorrhoea, hyperpigmentation, altered mood and hypertension

- Acromegaly (GH-secreting): skeletal overgrowth features (increased hand/foot size), hypertension, glucose intolerance, cardiovascular issues amongst others

- TSH-producing: rare but symptoms mimic hyperthyroidism – anxiety, palpitations, hyperhidrosis and weight loss

- FSH and/or LH-producing: rare

Alternatively, a large pituitary adenoma may lead to hormonal deficiencies and many non-specific symptoms that occur in relation to hypopituitarism.

Investigations

The initial work-up and evaluation must include bloods (particularly looking at hormonal changes), imaging to confirm the tumour, and a formal visual field assessment.

- Routine bloods (e.g. FBC, U&E, Coagulation)

- Pituitary profile: Early morning cortisol, prolactin, thyroid function tests, insulin-like growth factor, growth hormone, LH, FSH, testosterone, oestrogen

- Imaging: dedicated MRI pituitary with Gadolinium

- Visual field assessment

In general, symptomatic patients or those with a macroadenoma (i.e. > 1cm) need an extensive work-up. Those who are asymptomatic (e.g. incidental finding) with a microadenoma require less intensive investigations into the endocrine function, but a serum prolactin is still absolutely necessary.

Management

Depending on the type of adenoma, treatment is medical or surgical. Prolactinomas are managed medically with dopamine agonists (cabergoline, bromocriptine).

Surgical management for patients with Cushing’s disease or acromegaly, for example, involves endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery to remove the tumour. Steroid replacement (hydrocortisone) is often required post-procedure. Patients are at risk of developing diabetes insipidus and this needs to be monitored carefully by assessing the fluid balance and U&E (check Na+). If necessary, patients are given desmopressin as a one-off dose or more regularly.

The mainstay of treatment post-operatively is a review in a joint pituitary endocrine clinic. Many hospitals will also have a dedicated pituitary MDT to discuss cases in further detail

Pituitary apoplexy

Pituitary apoplexy refers to haemorrhage or infarction of the pituitary gland.

Pituitary apoplexy is a medical emergency that is due to acute haemorrhage or infarction of the pituitary gland. It most commonly occurs within the setting of a pituitary adenoma. The pituitary gland has a rich and complex vascular system. In the setting of an adenoma, there is an increased risk of haemorrhage and/or infarction due to the tumour 'outgrowing' its arterial supply. However, other pathological mechanisms have been proposed.

NOTE: Pituitary apoplexy may be seen in the postpartum period, which is referred to as Sheehan's syndrome. This is due to systemic hypotension from a postpartum haemorrhage and resultant ischaemic necrosis of the pituitary gland.

Pituitary apoplexy presents with sudden onset headache and/or neurological deficit and/or visual loss. The word apoplexy means 'sudden onset' or 'struck down'. Clinical suspicion is always needed for prompt recognition and the mainstay of investigation is urgent imaging (MRI ideally but out of hours only CT may be available) and blood tests. Urgent management involves hydrocortisone (due to hypopituitarism) and discussion with the neurosurgical team. Urgent surgery is usually reserved for patients with rapidly compromised vision but otherwise can be performed within seven days.

Brain metastasis

Brain metastases are the most common intracranial tumors in adults.

Metastasis refers to the spread of primary tumour to a secondary site such as the brain. In adults, brain metastases account for a significant proportion of brain tumours.

Some of the main cancers that can lead to brain metastasis include:

- Lung

- Breast

- Kidney

- Colorectal

- Melanoma

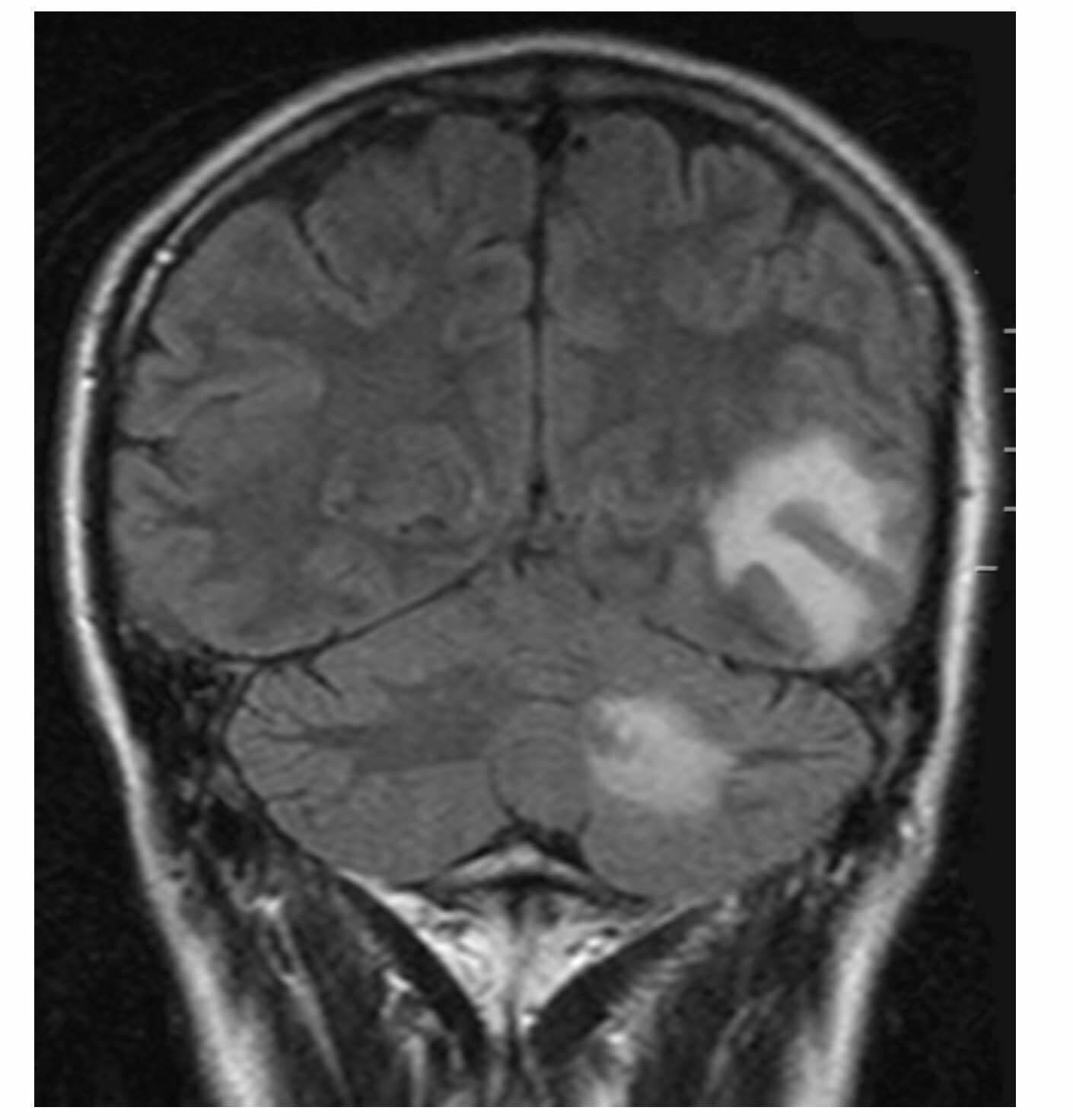

The most common site of brain metastasis is one of the cerebral hemispheres, which is the site in 80% of cases. Other locations include the cerebellum and brainstem. The site of metastasis within the central nervous system is affected by the type of systemic cancer. For example, breast cancer has a predilection for the posterior fossa.

Clinical presentation

The clinical features of brain metastases are common to all brain tumours and include features of raised intracranial pressure (e.g. headache, nausea/vomiting, swollen optic discs), focal neurological deficits (depending on the site) and seizures. Importantly, stroke is another common presentation seen in 5-10% of cases due to a variety of mechanisms. Some tumours have a propensity to bleed leading to intracerebral haemorhage that is most commonly seen in melanoma, thyroid and renal cancers.

Investigations

The principal investigation for suspected brain metastasis is neuroimaging with contrast-enhanced MRI being the preferred imaging. However, CT with or without contrast may be utilised in patients with acute presentations (e.g. stroke, seizure) due to the ease of access and speed of the test. Brain metastasis has some distinct features of neuroimaging that helps with the diagnosis.

Further investigations depend on whether the cancer is known, the patient's presentation and the decision for further therapy. In 80% of cases, the systemic cancer is already known at the time of diagnosis of brain metastasis. In 20-30%, the primary cancer remains unknown which leads to numerous investigations (e.g. CT CAP, tumour markers) in search of the primary site. These patients are often discussed at a special meeting known as the 'cancer of unknown primary' MDT, also known as 'CUP MDT'.

Brain metastases on MRI - coronal

Management

A variety of treatment options are available to patients with brain metastasis depending on the tumour type, the patients' performance status, and co-morbidities. Options may include:

- Radiotherapy: both stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) and whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) may be used. The main difference is that SRS is a targeted, localised therapy, whereas WBRT is a generalised therapy for the whole brain. There are various indications for using each therapy that go beyond the scope of these notes

- Surgery: usually reserved for a single site of metastasis that is easily accessible. May be combined with post-operative radiotherapy for local control of the tumour

- Systemic treatments: chemotherapy, immunotherapy and other oncological treatments may be used as part of the overall treatment strategy for these patients. The use of immuno- and targeted therapies, in particular, is a rapidly growing area

Acute management

One of the profound effects of brain metastasis is the development of vasogenic oedema. This refers to swelling around the site of the tumour due to disruption of the blood-brain barrier and leakage of protein-rich fluid in the extracellular space. Vasogenic oedema contributes to the symptoms associated with brain tumours including raised intracranial pressure, focal neurological, and seizures.

The primary treatment of vasogenic oedema is the use of high-dose intravenous steroids (e.g. dexamethasone) that can have a rapid and profound effect on symptoms. The actual mechanism behind why steroids work for vasogenic oedema is incompletely understood but may be related to its effect on the downregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). It is important they are combined with gastric protective medications (e.g. proton pump inhibitors).

Prognosis

Historically, the median overall survival for patients with brain metastasis was poor and normally < 6 months. However, with the advent of improved oncological treatments, the median survival is now 8-16 months, although a lot depends on the tumour type.

Last updated: November 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback