Cauda equina syndrome

Notes

Overview

Cauda equina syndrome is due to compression of the collection of nerves distal to the terminal part of the spinal cord known as the cauda equina.

The cauda equina, which is Latin for ‘horses tail’, refers to the collection of spinal nerves that lie within the subarachnoid space distal to the last part of the spinal cord known as the conus medullaris. Compression of the cauda equina leads to a syndrome characterised by lower limb weakness, bladder and bowel dysfunction, and abnormal perianal sensation. It is considered a neurosurgical emergency.

While not a true spinal cord lesion, cauda equina syndrome is usually discussed alongside the other spinal cord syndromes because of its close proximity and shared aetiology (e.g. malignancy).

For more information on disorders affecting the spinal cord, see our notes on Cord compression and Spinal cord syndromes.

Anatomy

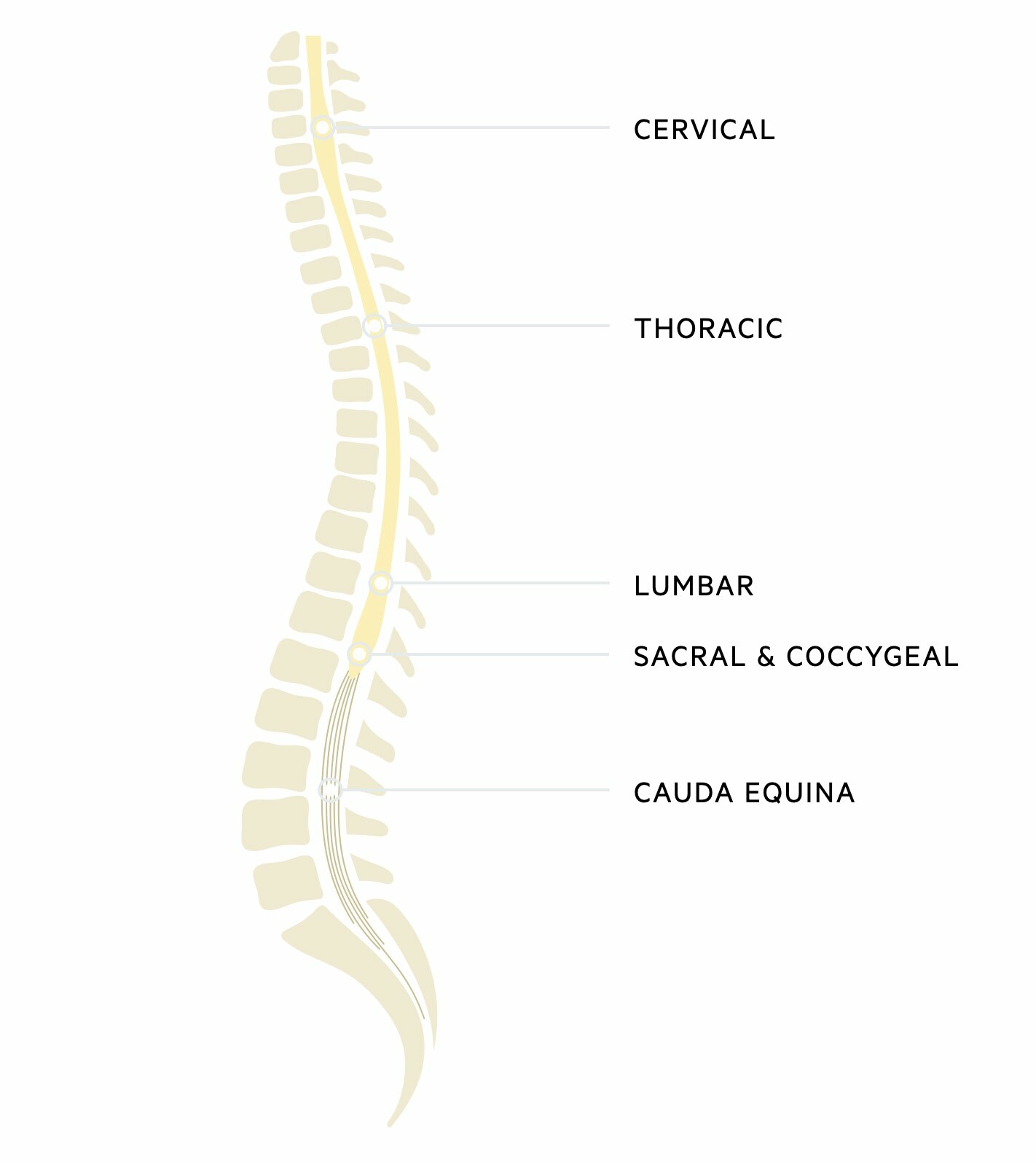

The spinal cord is part of the central nervous system (CNS) and forms the main communication between the brain and peripheral nerves.

The spinal cord originates at the base of the medulla oblongata, exiting the skull through the foramen magnum. It then extends through the spinal canal and ends at the level of the L1/L2 spinal vertebrae.

It is divided into four main regions termed cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral. This is further divided into 31 spinal cord segments. Arising from the 31 spinal cord segments are the paired ventral and dorsal spinal nerve roots, which join to form the 31 paired spinal nerves.

Cauda equina

The terminal end of the spinal cord is termed the conus medullaris. Beyond this is a collection of spinal nerves composed of lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal nerves. Together these make up the cauda equina. These nerves have important innervation for lower extremity motor function, perianal sensation, and parasympathetic sensation to the bladder and bowel including the sphincters.

Epidemiology

Cauda equina syndrome is a rare condition.

Cauda equina syndrome has a low global incidence with no large data reporting the prevalence of the condition. It is estimated to account for 2-6% of lumbar disc operations and a UK GP may go their entire career without seeing a complete case.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

Any narrowing of the spinal canal at the level of the cauda equina can give rise to the syndrome.

Cauda equina syndrome may be caused by a variety of pathologies that lead to narrowing of the spinal canal from L1/2 downwards. This narrowing leads to compression of several, or many, of the nerves contained within the cauda equina.

Common causes include:

- Lumbar stenosis: narrowing of the spinal canal in the lumbar region

- Spinal trauma

- Disc disease: herniation of the disc

- Malignancy: primary tumour of the nervous system or metastasis

- Spinal infections: abscess, tuberculosis

- Neural tube defects (e.g. spinal Bifida)

The cauda equina contains nerves that exit from the spinal cord and form part of the peripheral nervous system. Therefore, patients usually have features of a lower motor neuron weakness (i.e. low tone, weakness, hyporeflexia, downing plantars). Patients with a lesion of the spinal cord have evidence of upper motor neuron weakness (i.e. high tone, weakness, hyperreflexia, upgoing plantars).

Clinical features

Cauda equina syndrome is characterised by low back pain, leg weakness, saddle anaesthesia, and bladder/bowel dysfunction.

The presentation of cauda equina syndrome depends on the acuity of the underlying pathology and the distribution of nerves that are affected within the cauda equina. Many patients present with acute pain and neurological deficits, but a more chronic presentation over weeks to months can occur.

It should always be suspected in low back pain and new-onset neurological deficits. Asymmetrical, unilateral (or bilateral) sciatica-like pain (shooting pain due to irritation of lumbosacral nerve roots) with new neurological deficits in the lower limb and bladder/bowel dysfunction is classic.

Symptoms

- Low back pain

- Asymmetrical sciatica pain

- Saddle anaesthesia: reduced or absent sensation around the perineal skin

- Bladder dysfunction: urinary retention, difficulty passing urine, overflow incontinence

- Bowel dysfunction: constipation, incontinence, loss of anal tone

- Lower limb weakness: often asymmetrical

Signs

- Hypotonia

- Leg weakness

- Hyporeflexia

- Leg sensory changes: may have abnormal sensation along a single dermatome

- Reduced sensation around perianal area

- Loss of anal tone (on PR examination)

- Palpable bladder

Differential diagnosis

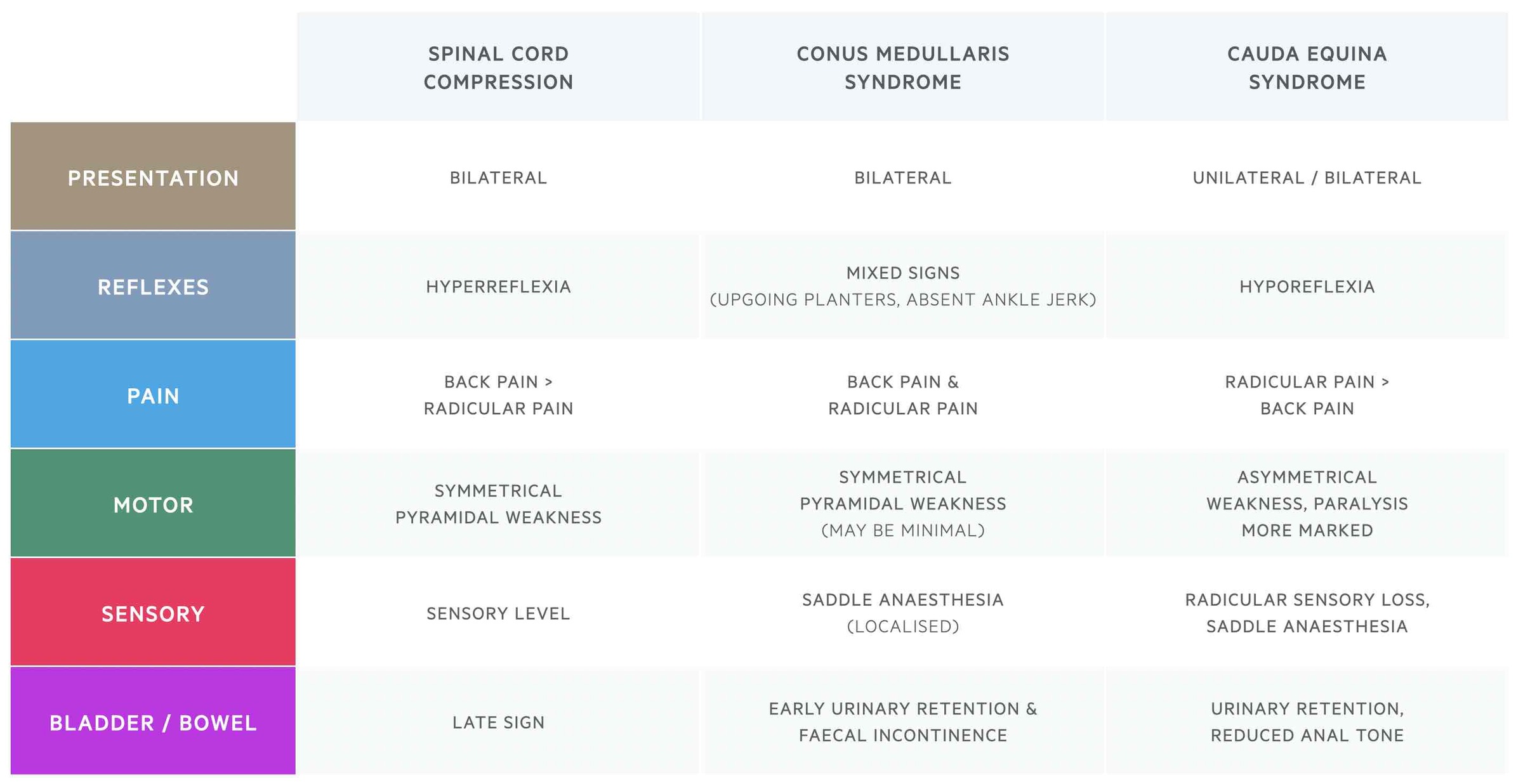

It is important to differentiate between three conditions that all lead to back pain and neurological deficits. These are Cauda equina syndrome, Conus medullaris syndrome, and Cord compression.

- Cauda equina: compression of the lumbosarcal nerve roots that make up the cauda equina. These are peripheral nerves and therefore compression causes a lower motor neuron pattern of weakness.

- Conus medullaris: compression of the last part of the spinal cord at L1/L2. Compression at the conus causes a clinical picture similar to cauda equina but with mixed neurological signs (upper and lower motor neuron features) as it also affects part of the cord.

- Cord compression: compression of the spinal cord at any level within the cervical, thoracic or lumbar region. Following the acute insult, this causes a classical upper motor neuron pattern of weakness.

NOTE: acute cord compression usually causes flaccid paralysis (i.e. low tone and hyporeflexia). Over time, the pattern of weakness classically becomes upper motor neuron with features of high tone and hyperreflexia.

The key differences between these conditions are shown in the table below:

Diagnosis & investigations

The principal investigation for the diagnosis of suspected cauda equina is an MRI spine.

Patients with suspected cauda equina should be referred urgently to accident and emergency for assessment and imaging of the spine. The reliability of a clinical diagnosis of Cauda equina syndrome is low. This means there should be a low threshold for performing an MRI spine in suspected cases.

MRI should be performed as soon as possible. In metastatic cord compression, MRI is recommended within 24 hours of presentation. CT of the spine is not recommended for the diagnosis but may be an alternative for patients who are unable to undergo MRI imaging.

Basic investigations should be requested looking for a possible underlying cause, any complications and in preparation for surgery (e.g. blood gas, basic blood tests, coagulation, group & save, ECG, bladder scan).

Management

Cauda equina syndrome is a neurosurgical emergency.

Cauda equina syndrome is considered a neurosurgical emergency, requiring operative management to prevent symptom progression and permanent paralysis.

Patients with Cauda equina syndrome should be discussed urgently with the most appropriate regional service (e.g. neurosurgeons, spinal orthopaedic team). The decision to proceed with emergency surgery depends on the acuity of the presentation and the extent of neurological dysfunction. The type of surgery depends on the aetiology with the overall goal to improve the space within the spinal canal and remove the agent leading to compression (i.e. decompressive surgery)

Patients with evidence of bladder dysfunction (e.g. urinary retention) generally need immediate surgery.

Complications

Without intervention, cauda equina syndrome can lead to permanent paralysis.

There are many long-term complications associated with Cauda equina syndrome that include:

- Bladder and bowel dysfunction

- Sexual dysfunction

- Chronic pain

- Paralysis

- Pressure ulcers

Last updated: June 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback