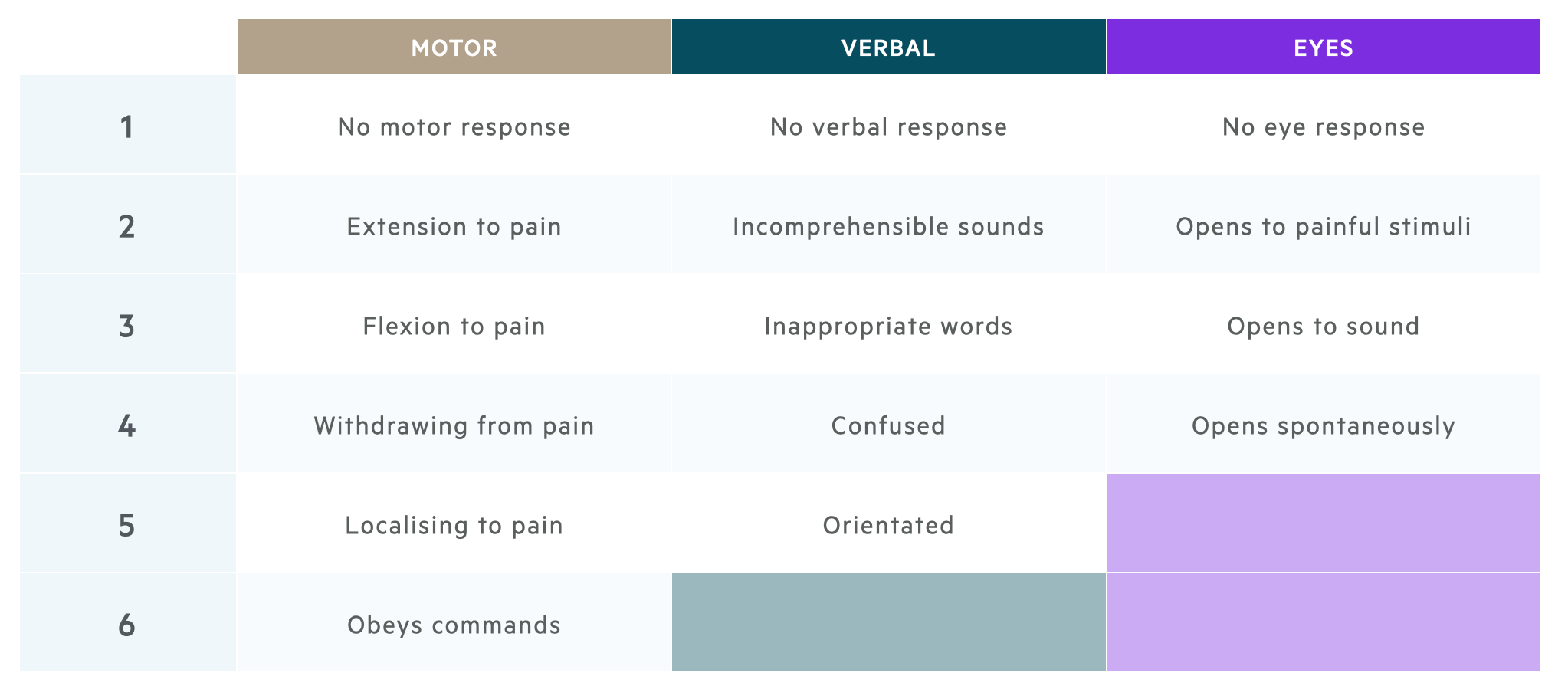

Chronic subdural haematoma

Notes

Definition

Subdural haematoma is a collection of blood in the subdural space.

Subdural haematoma (SDH) refers to a collection of blood in the subdural space. This is situated underneath the dura and above the arachnoid mater meningeal layers. There are several classifications of SDH:

- Acute (ASDH): bleeding occurring in the last 1-3 days.

- Chronic (CSDH): blood that has usually been present for > 3 weeks.

- Subacute: bleeding that occurs between 4 days and 2-3 weeks.

- Acute on chronic: chronic haematoma that may expand secondary to recurrent bleeding.

Aetiology

The most common cause of CSDH is trauma.

The most common cause of CSDH is trauma in nearly 50% of patients. However, most may not even recall the injury as it is often trivial.

Other causes include:

- Epilepsy

- Haemophilia

- Cerebral aneurysms (rarely)

- Neoplasms

A CSDH may develop if the patient has a shunt inserted for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage. Over-drainage can cause a bleed. Another rare pathology includes spontaneous intracranial hypotension secondary to a CSF leak. This may cause a CSDH due to chronic brain ‘sagging’.

Risk factors

The risk factors associated with development of CSDH include:

- Age

- Alcohol misuse or dependency

- Bleeding disorder

- Anticoagulation and/or antiplatelet use

Anatomy & pathophysiology

The brain is encased in three meningeal layers: the dura, arachnoid and pia mater.

In order to understand the anatomy of a subdural haematoma (chronic or acute), we need to understand the anatomy of the meninges.

Meninges

The brain is encased in three meningeal layers, which are the dura, arachnoid and pia mater (outside to inside). The pia mater is adherent to the surface of the brain and spinal cord. The subarachnoid space is found between the arachnoid and pia mater. The subdural space, a potential space, is found between the dura and arachnoid mater.

Tearing of a bridging or surface vein causes blood to escape into the subdural space.

Pathophysiology

A CSDH invariably starts out as an acute subdural haematoma. There is often an initial injury that may be trivial at the time (if the patient can recall it) which slowly becomes chronic over time. The haematoma occurs due to tearing of a surface or bridging vessel often as the result of innocuous trauma.

The mechanism behind CSDH formation is likely multifactorial and goes beyond a tear of a bridging vein. The subdural blood provokes an inflammatory response with likely neoangiogenesis (growth of new blood vessels) and coagulopathy (abnormal clotting). Indeed, during an operation, membranous formations are often identified and the subdural collection themselves often resemble motor engine oil which is not clotted.

CSDH tends to affect elderly patients more than younger patients and the mechanism of injury is usually innocuous. Due to the degree of brain atrophy the intracranial vault is able to accommodate a significant amount of blood before symptoms develop, which is often the reason why patients present several weeks to months following the injury.

Clinical features

Patients most typically present with an insidious onset of headaches.

A variety of signs and symptoms may develop following a subdural haematoma, which may be many weeks or months following the initial injury. Global neurological deficits (e.g. altered consciousness) are more commonly seen than focal neurological deficits (e.g. contralateral weakness).

Symptoms

- Headache

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Weakness (hemiparesis)

- Speech disturbance (if dominant hemisphere affected)

- Personality changes (emotional outbursts, mania, depression)

Signs

- Altered mentation (confusion)

- Focal neurological deficit

- Hemiparesis/hemiplegia

- Dysphasia

- Reduced GCS or coma

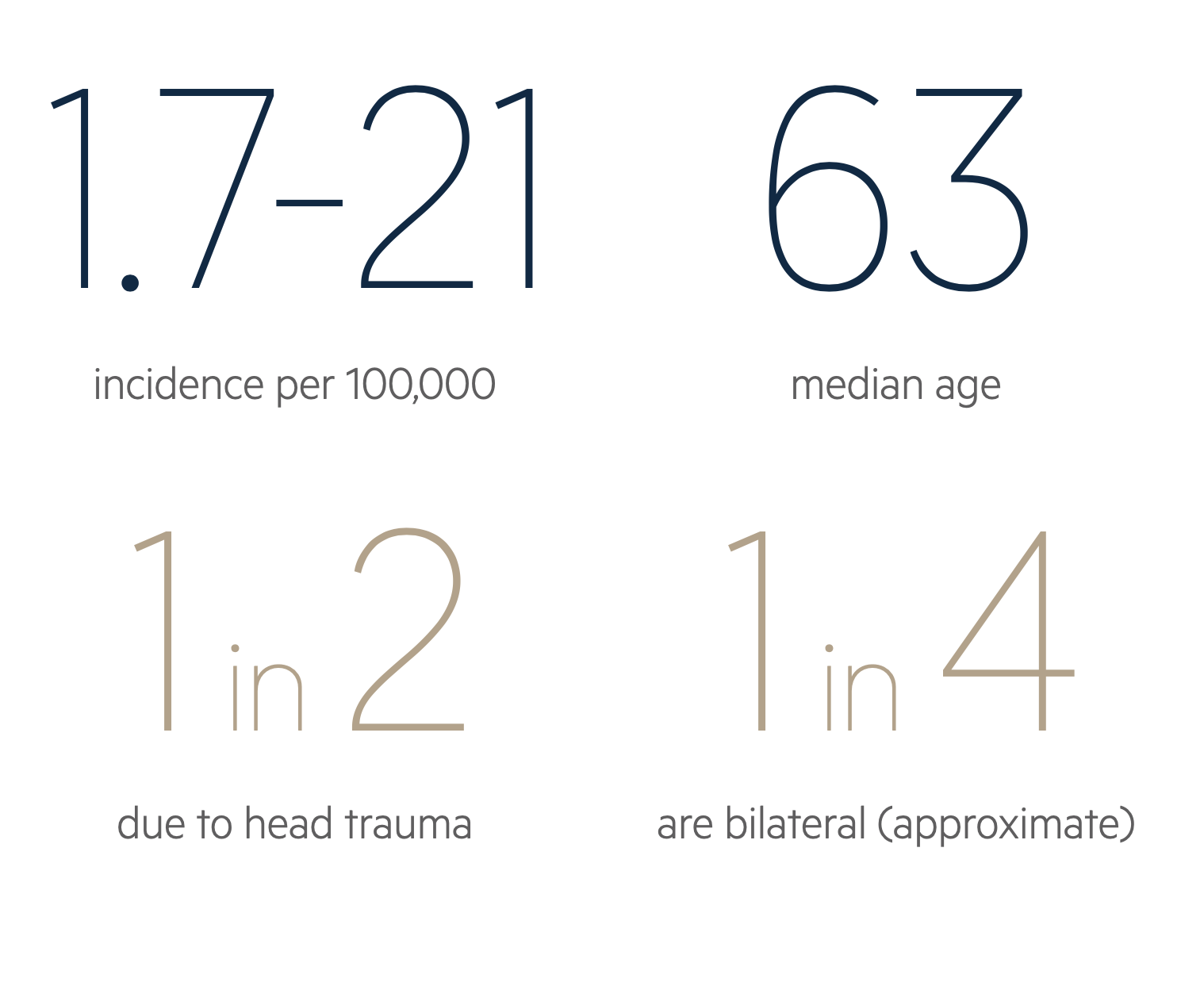

Glasgow Coma Score

The Glasgow Coma score is a clinical scale used to reliably measure a person's level of consciousness after a brain injury.

It is important to be familiar with the Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) which is measured from 3 to 15 and has three elements.

- Motor response (1-6)

- Verbal response (1-5)

- Eye response (1-4)

Please remember, the best possible score in each category is recorded and one has to adapt (for instance, if the patient has weakness on one side, you can assess obeying commands by asking the patient to stick out their tongue).

Diagnosis

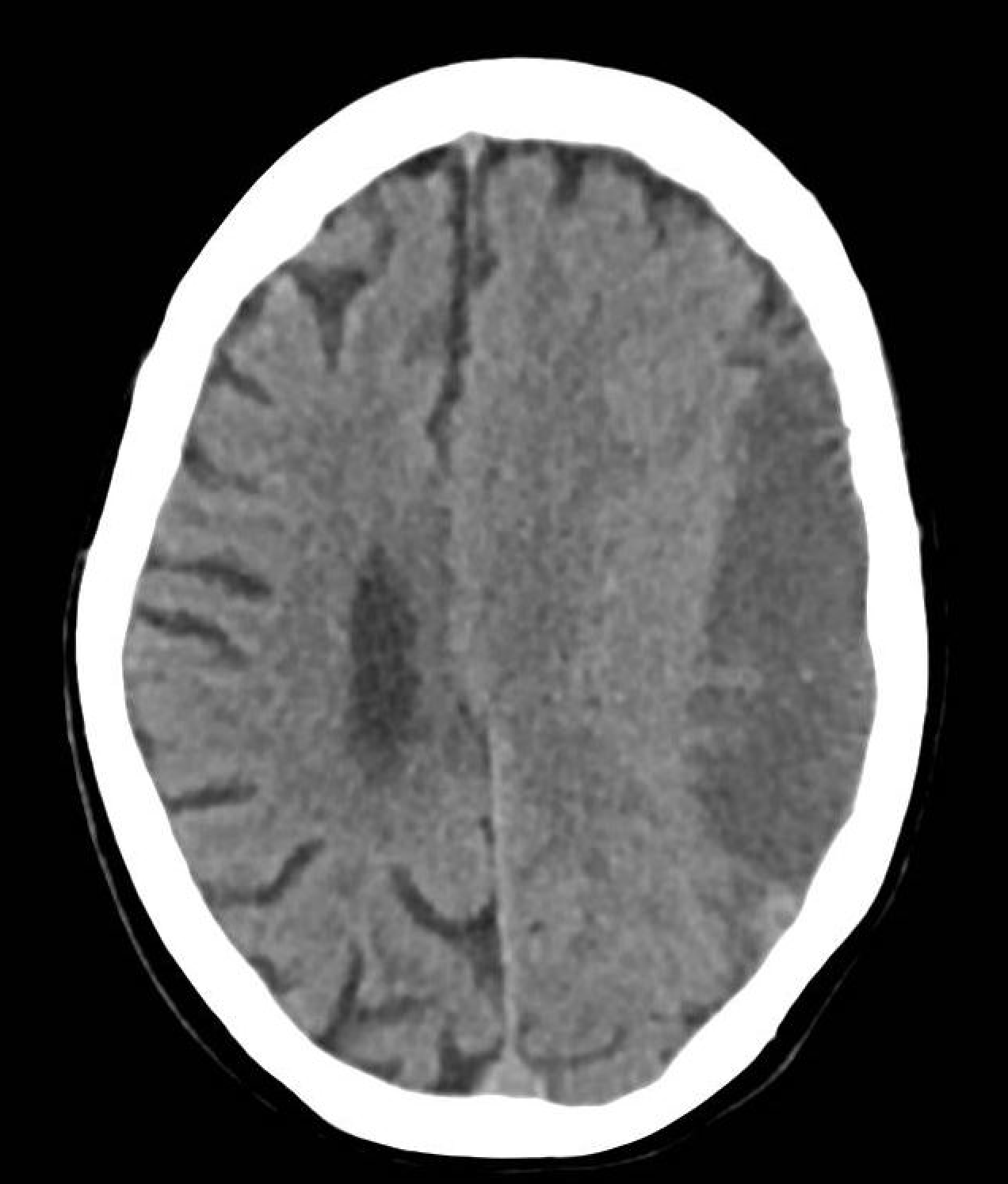

A CT head is the investigation of choice for the diagnosis of CSDH.

The diagnosis of a CSDH is rooted in the history (e.g. trauma) and examination (e.g. altered mental status). A definitive diagnosis is then made with imaging (CT head). However, because the initial injury is often trivial and clinical signs subtle, the diagnosis may not be obvious from the initial clinical assessment. Therefore, a high index of suspicion should be used, especially in older patients on anticoagulation or anti-platelets.

The principle investigation is a non-contrast CT head that will show blood within the subdural space. It will appear as an isodense or hypodense crescent-shaped lesion on CT. The density of the blood depends on the timeframe. An acute subdural haematoma will appear as high-density with white material.

A large or rapidly expanding SDH may show mass effect with distortion of the normal anatomy.

CT head showing a chronic left-sided subdural haematoma.

Bilateral CSDH

Always be suspicious and suspect underlying pathology if you detect a bilateral CSDH. This is often not due to trauma and there may be an underlying cause. Pay particular attention if the patient is young as this may be part of a phenomenon known as spontaneous intracranial hypotension and rather than surgical drainage, the patients needs further work-up such as MRI whole spine to check for a tethered cord or CSF leak. Alternatively, there could be an underlying coagulopathy.

Investigations

Basic investigations (e.g. bloods) are critical to the work-up of CSDH because patients may require surgery.

Basic investigations are critical to work-up patients with a suspected CSDH to enable planning for surgery (if required), assessing for sequelae of trauma (if present) and determining the aetiology (if unknown).

Bedside

- Neurological observations: monitoring of GCS

- Blood glucose

- ECG

Bloods

- FBC - check for anaemia and thrombocytopenia

- U&E - check the electrolytes, especially sodium

- LFT - disorder or history of alcohol abuse

- Bone Profile - check for calcium

- Coagulation - check for clotting disorder

- G&S - consider if going for surgery

- Crossmatch - for blood products such as FFP, platelets and packed red blood cells

Imaging

A CT head is the imaging of choice for detection of a subdural haematoma. Consider need for additional imaging depending on the mechanism of injury and other clinical features. There may be a history of recurrent falls, particularly in the elderly.

Management

The management of CSDH has several key elements: initial management, medical management and surgical management.

Initial management

Patients with a CSDH can present alert or with reduced consciousness. Often they will be communicative and give a history, albeit they may be confused. This is assessed using the Glasgow Coma Score. A systematic ABCDE is utilised in emergency settings.

Medical management

A patient presenting with a suspected CSDH should be monitored closely with neuro-observations. Not every CSDH is suitable for operative management and a proportion of cases are managed medically or conservatively.

The decision for operative versus conservative management is dependent on multiple factors including:

- SDH size

- Mass effect

- Neurological compromise

- Pre-morbid status (e.g. frailty, cardiovascular co-morbidities, suitability for anaesthesia, anticoagulant/antiplatelet use)

There may be instances where patients are monitored for a period of time before they are discharged home and followed with interval imaging. This is to wait for the SDH to become more ‘chronic’ and ‘liquefy’ so that it is more amenable to surgical drainage.

You may notice some cases managed with dexamethasone (steroid) due to the inflammatory process involved in formation of a subdural haematoma. However, this is becoming less common and a trial is underway to determine whether this strategy works for CSDH.

Surgical management

Surgical management of a CSDH is usually with a simple operation known as burrhole drainage. This can be performed under local or general anaesthesia. Local anaesthesia is sometimes used with or without sedation if the patient has several co-morbidities which precludes a general anaesthetic.

Usually two incisions are made on the side of the head with the SDH (e.g. frontal and parietal region). The bone is drilled and two holes are fashioned. The dura is carefully opened and the collection is washed out using copious solution. A drain may be left to remove any residual. Historical procedures that are no longer common place include twist drill craniostomy and embolisation of the middle meningeal artery.

Complications

A common complication of CSDH is seizures due to direct cortical irritation.

CSDH, if managed operatively, can recur and there are instances of patients requiring repeated drainage. If the patient is on an antiplatelet or anticoagulant there is a risk of bleeding and a CSDH has been known to develop an acute component (i.e. acute on chronic).

As always with a neurosurgical procedure, there are additional risks such as infection, stroke, seizure, paralysis and no improvement. If the patient has a prolonged stay in hospital, there is a chance of associated pneumonia, urinary infections, DVT/PE.

Last updated: July 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback