Burns

Notes

Summary

Burns result from damage to skin & deeper tissues caused by external sources or substances.

Burns are a major cause of injury and death worldwide. They can have devastating physical and psychological effects on an individual, that can lead to chronic disability. They may be caused by thermal, chemical, frictional or electrical injury.

Mortality is increased with large burns, with increasing age and with associated inhalational injury. Effective management necessitates a multi-disciplinary approach.

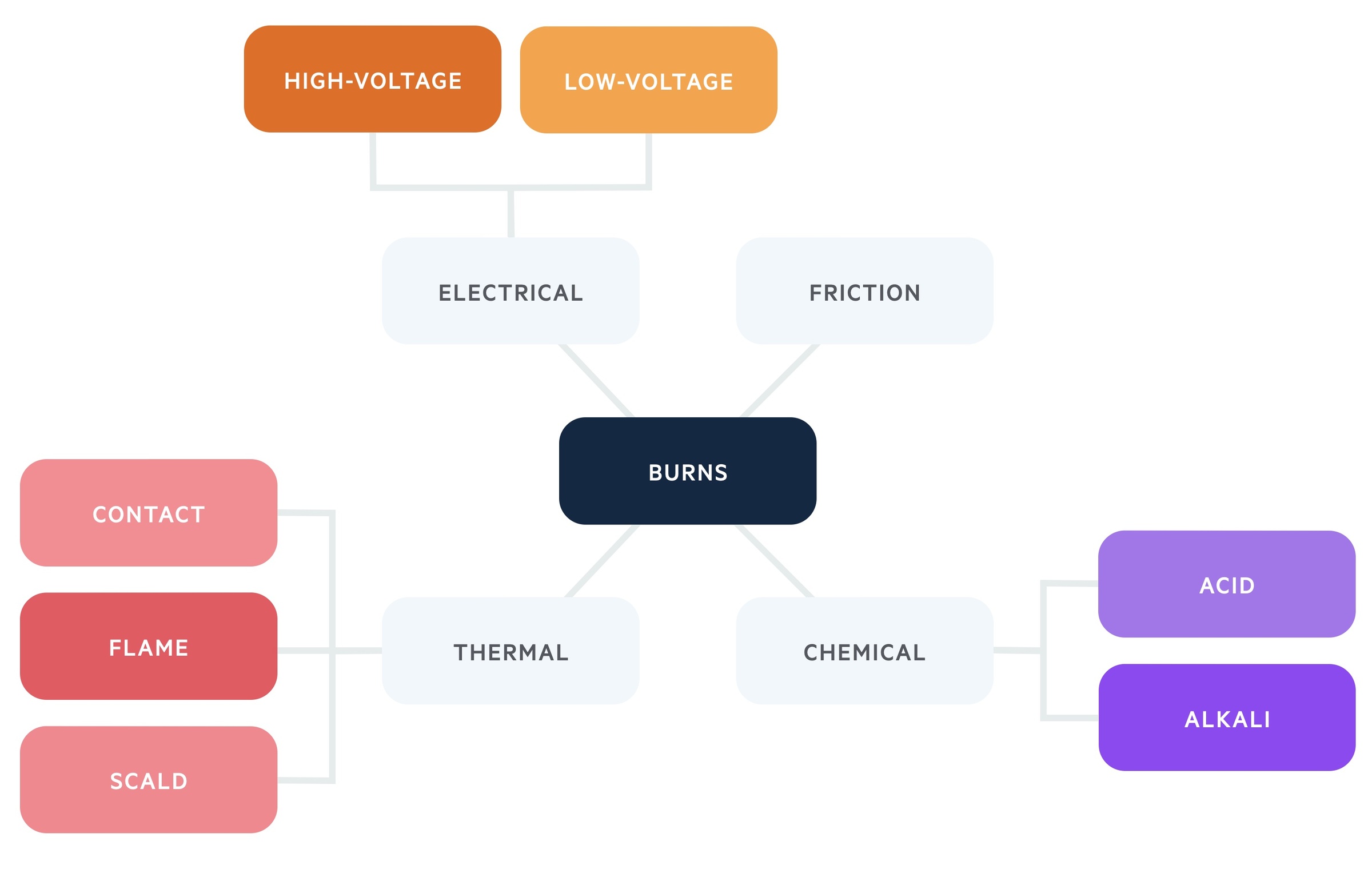

Aetiology

Most burns are thermal injures due to scalds, contact & flame burns.

Burns may be thermal, chemical, frictional or electrical. Thermal injuries are the most common and include scalds, contact and flame burns.

Epidemiology

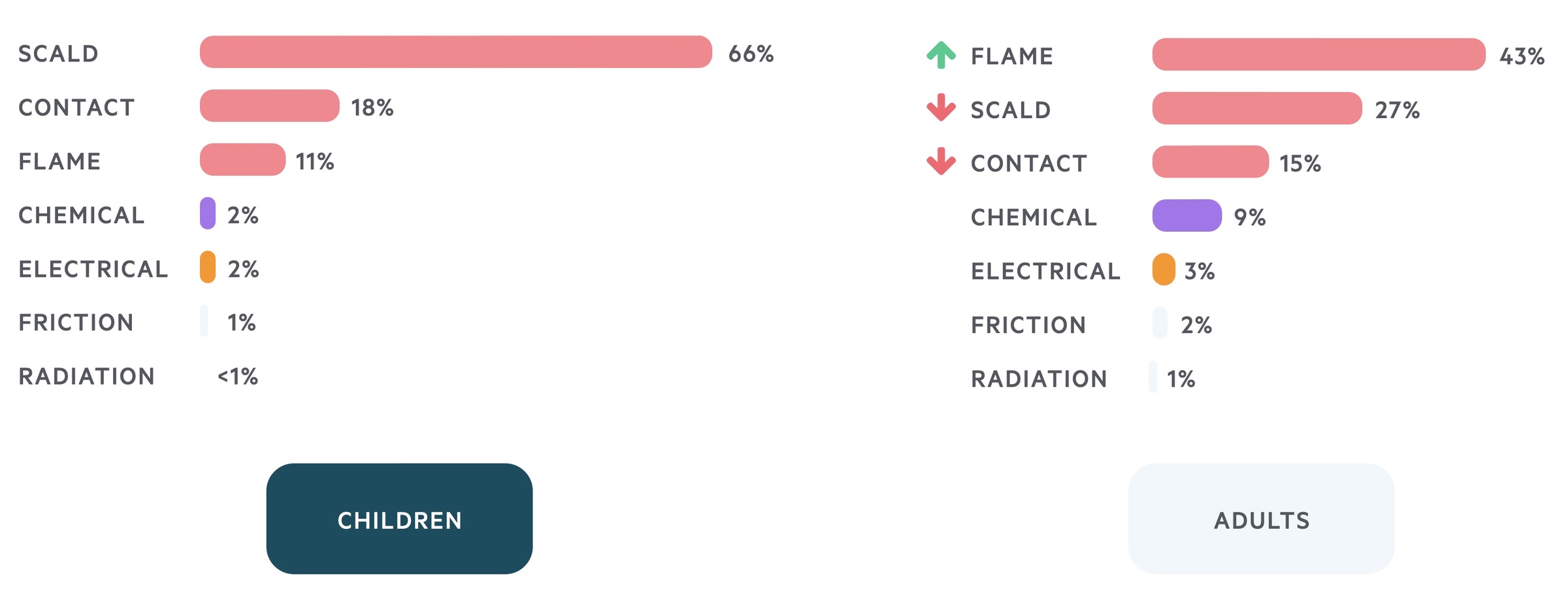

A common form of trauma, in both adults & children, the likeliest place to be burnt is the home.

In the UK, approximately 250,000 burns occur each year. Of these, roughly 10% (25,000) require hospitalisation and around 1% (2,500) are life-threatening, with roughly 300 deaths. The UK incidence is fairly representative of the developed world.

Burns are common in both children and adults, although different types of burn are prevalent in each group. The likeliest place to be burnt is in the home.

Burns are also a substantial problem in the developing world. Sadly, mortality in these countries is typically much higher.

Pathophysiology

Local response

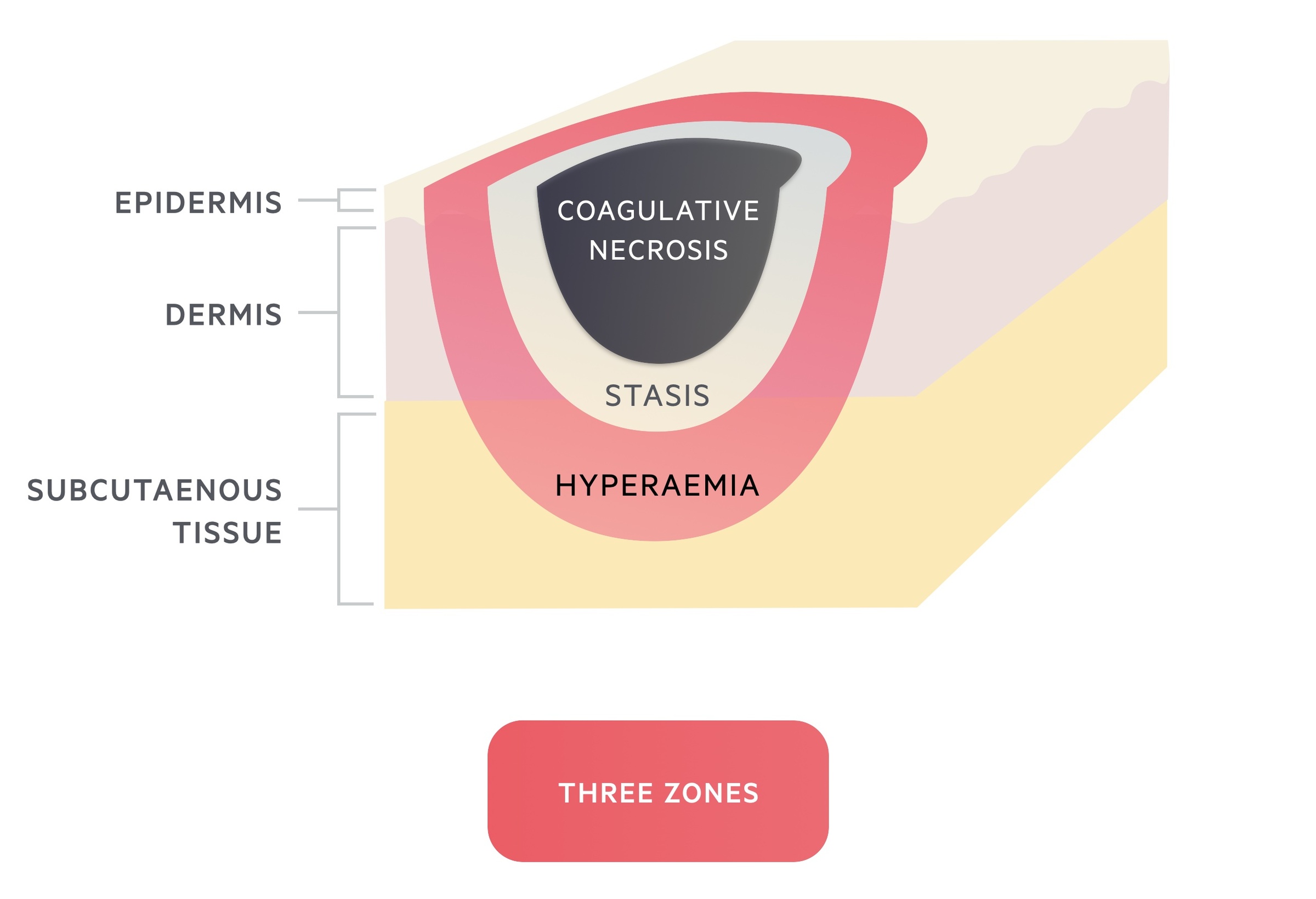

Jackson's burn wound model is a model for understanding the local response of burns wounds.

Three zones of a burn wound were described by Jackson in 1947:

- Zone of coagulative necrosis - Area nearest to the heat source (or other injuring agent). Results in immediate coagulation of proteins leading to irreversible cellular death.

- Zone of stasis - Damage in this area is less severe but there is compromised circulation. Untreated, this area undergoes necrosis as the injury progresses. Observed clinically as the progression of the depth of a burn over several days (3-5 days). The tissue in this zone is potentially salvageable.

- Zone of hyperaemia - In the outermost zone inflammatory mediators cause widespread dilatation of blood vessels. Provided there is resolution of hyper-dynamic response, tissues will recover.

Systemic response

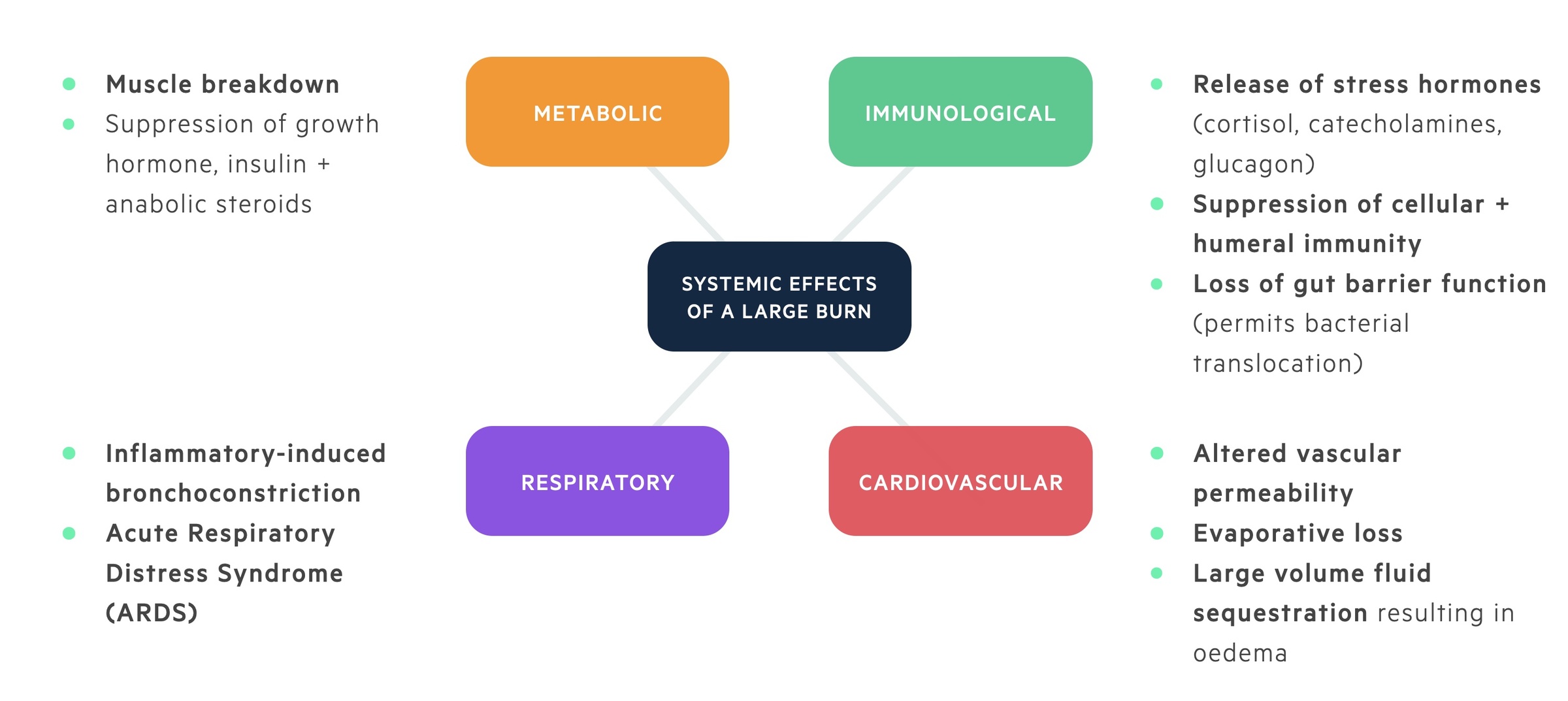

In a burn that covers >25-30% of total body surface area (TBSA), widespread release of inflammatory mediators results systemic effects.

In large burns, cytokines and inflammatory mediators result in a number of systemic effects:

- Cardiovascular - Altered vascular permeability results in leaky capillaries with the loss of intravascular proteins. Large volumes of fluid are lost through evaporation (loss of normal skin function) and fluid sequestration (third spacing). Result - systemic hypotension + reduced end organ perfusion.

- Respiratory - Inflammatory-induced bronchoconstriction. Severe burns can also result in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Result - impaired tissue oxygenation.

- Metabolic - Basal metabolic rate (BMR) increases up-to three times. Result - hyper-metabolism, breakdown in muscle protein.

- Immunological - Release of stress hormones (cortisol, catecholamines, glucagon) result in the suppression of both cellular and humeral immunity. Loss of normal gut barrier function can permit bacterial translocation resulting in sepsis. Result - immunosuppression, increased susceptibility to infection.

Assessment

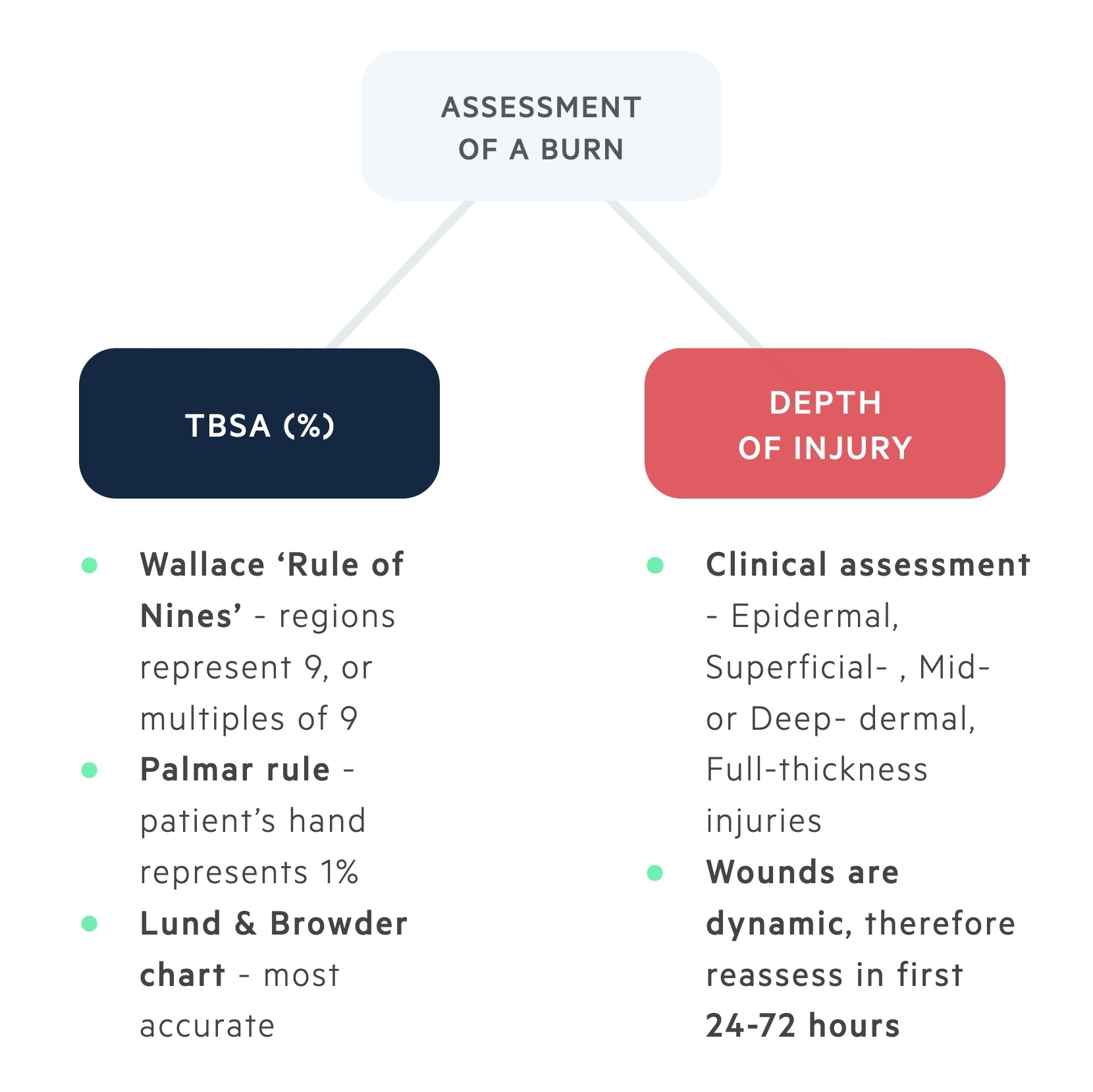

TBSA and depth of injury are vital in the initial assessment of a burn wound.

TBSA

Three common methods of estimating burn surface area

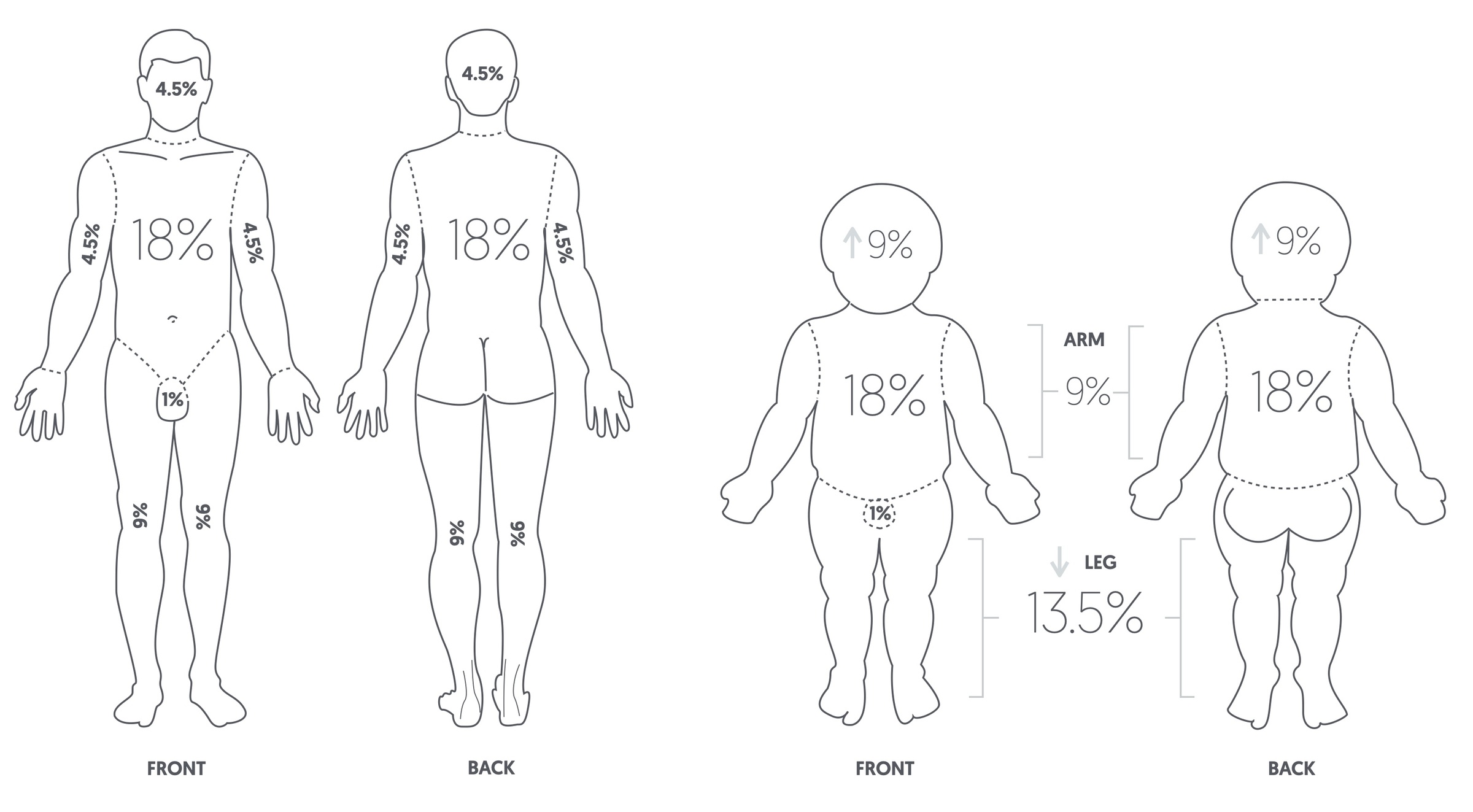

- Wallace ‘Rule of Nines’ - The adult body is divided into anatomical regions that represent 9, or multiples of 9. Therefore 9% for the head and each upper limb; 18% for each lower limb, the front of trunk and back. In children, the legs are smaller (13.5%) and the head is double the size (18%).

- Palmar rule - The palmar surface of the patient's hand (including the fingers) represents approximately 1% of the patient's body surface. Useful for small (<15%) non-confluent burns. Conversely, useful for very large (>85%) burns when the non-burnt area is counted.

- Lund & Browder chart - Most accurate method of estimation. Takes into account that children of differing ages have varying proportions to adults.

Wallace 'Rule of Nines' for adults and children

Depth of injury

Estimation of burn depth is difficult. Furthermore, the depth of a burn may transition over the first 3-5 days.

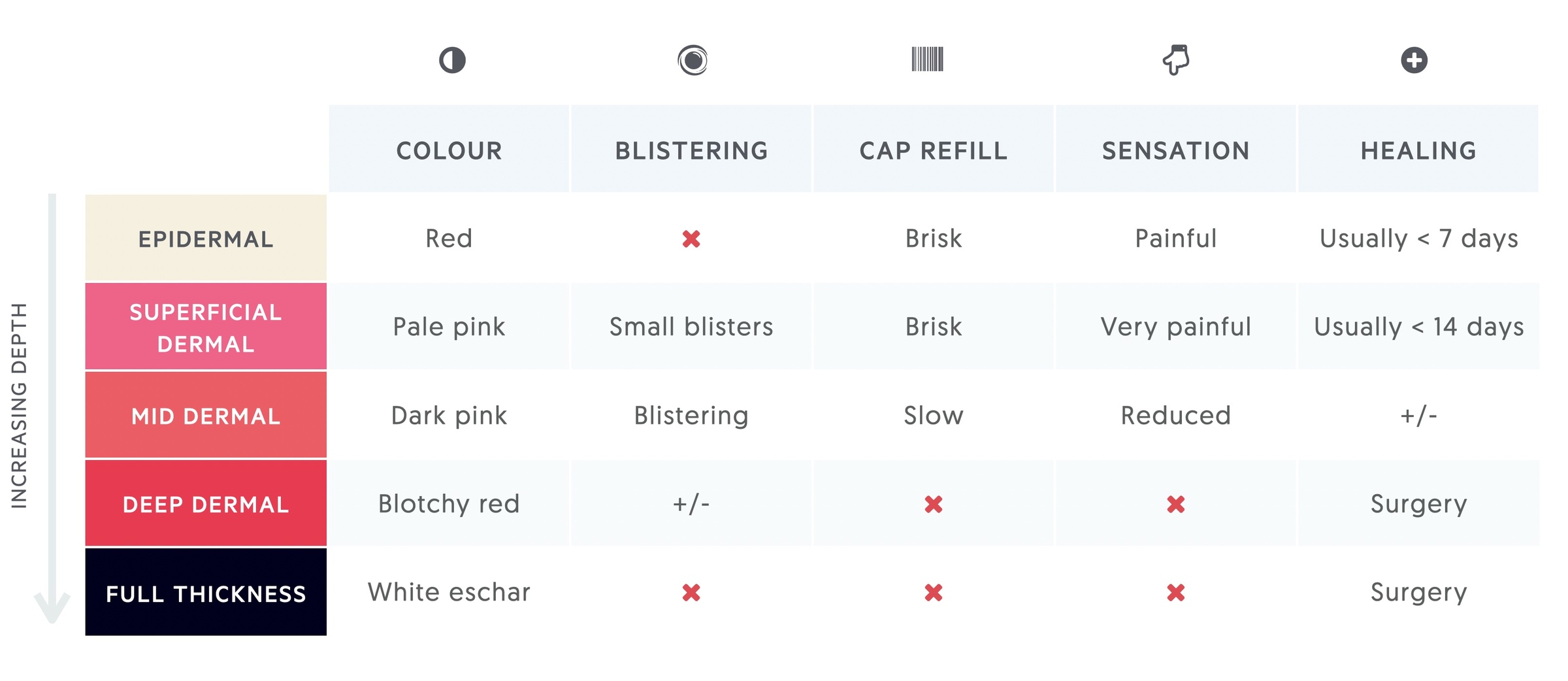

The depth is relative to the energy of the burn and the thickness of the skin. Burns are graded according to increasing depth (epidermal, superficial dermal, mid-dermal, deep-dermal, and full-thickness).

Burn wounds are assessed clinically using the following:

- Colour - Epidermal burns are red. Dermal burns transition from pale pink (superficial), to dark pink (mid-dermal), to blotchy red (deep-dermal), with increasing depth. Full-thickness burns have a thick white-eschar (dead-tissue).

- Blistering - Epidermal burns do not blister. However, blistering is typically seen in burns affecting the upper dermis (superficial- and mid-dermal burns). Once down to the deep-dermis, blistering does not occur.

- Capillary refill - Surface blood flow is increased in epidermal burns resulting in a brisk refill time (< 2 seconds). As the burn depth increases, capillary refill diminishes until it is non-existent (fixed staining). This is due to injury to the dermal blood vessels (dermal plexus).

- Sensation - Pain is observed in epidermal and superficial dermal burns. Deeper dermal or full-thickness burns may have reduced sensation or be insensate. This is due to damage of the cutaneous nerves.

- Healing - Spontaneous healing occurs with epidermal burns usually within 7 days. Superficial dermal burns may take unto 14 days and may heal with pigmentation changes. Mid-dermal burns can go either way. They may heal spontaneously (with increased risk of hypertrophic scarring or pigmentation changes) or they may need surgical debridement and reconstruction. Deep-dermal and full-thickness burns inevitably require surgical intervention.

In clinical practice, most burns are a mixture of different depths. Burn wounds are also dynamic and reassessment should be performed following resuscitation.

Acute management

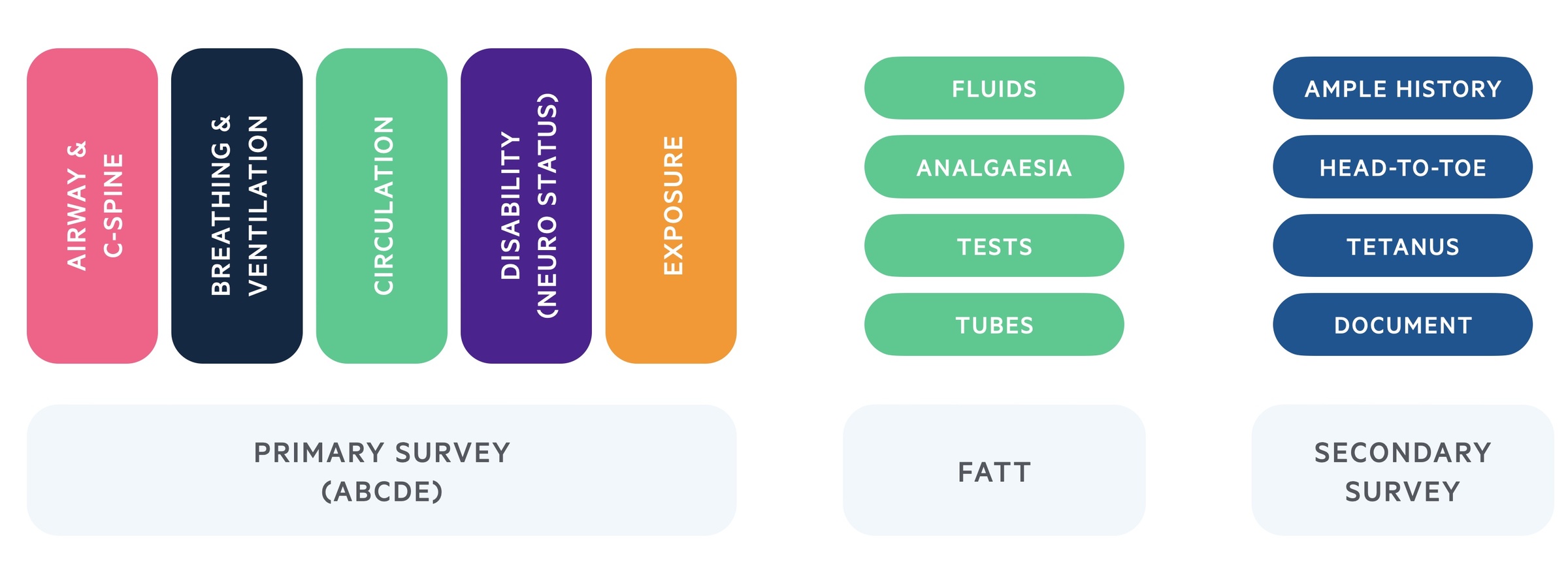

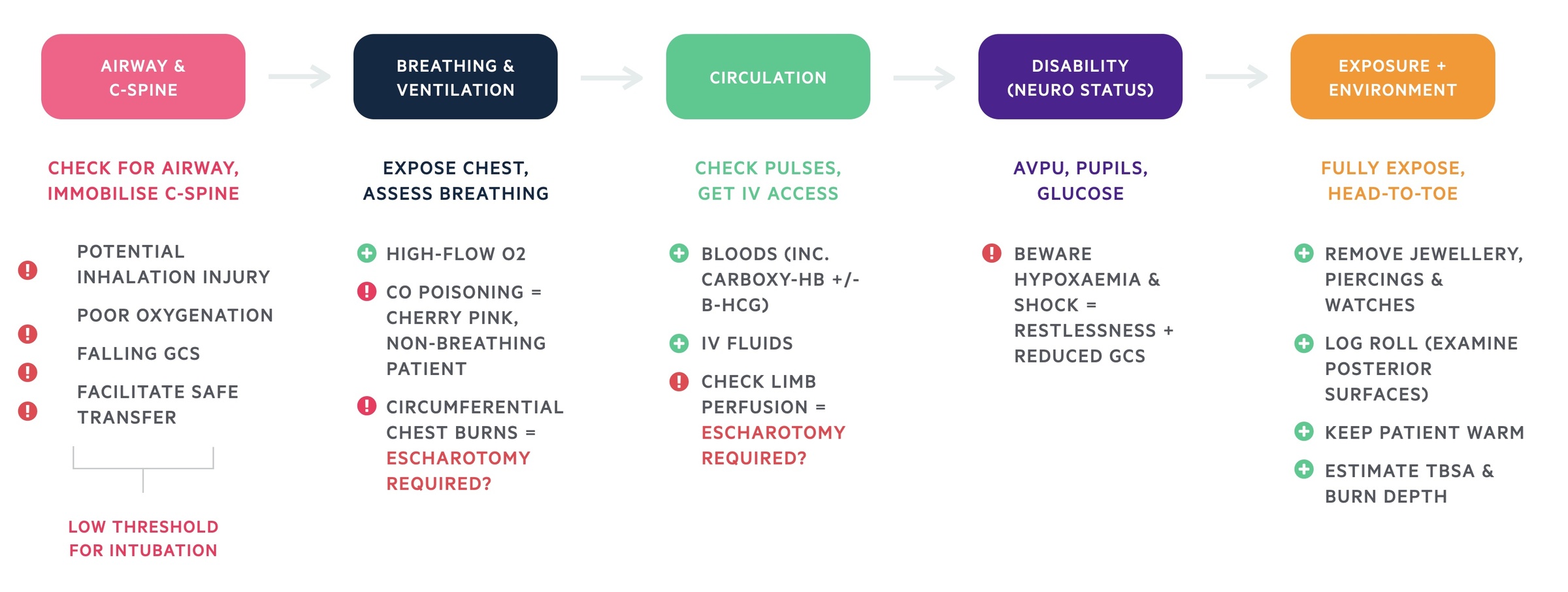

Acute severe burns are managed using a modified advanced trauma and life support (ATLS) algorithm.

This consists of three elements:

- Primary Survey (ABCDE)

- Fluid resuscitation, analgaesia, tests & tubes (FATT)

- Secondary Survey

Primary survey

A - Airway and C-spine immobilisation

Priority is to ensure the airway is patent and cervical-spine protected.

Although the airway may be patent on arrival, this may change, especially with the initiation of fluid resuscitation.

Inhalational injury may occur from the inhalation of hot gases or products of combustion resulting in oedema above the level of the vocal cords or direct injury to the respiratory tract. It is particularly associated with burns to the head and neck or burns sustained in an enclosed space (e.g. house fire).

Indications for intubation include:

- Potential inhalational injury

- Poor oxygenation

- Falling consciousness

- Facilitation of safe transfer

Essentially, if in doubt intubate.

B - Breathing and ventilation

Expose chest and assess breathing.

100% humidified oxygen should be administered via a non-rebreathe mask.

Breathing may be compromised by:

- Inhalational injury - direct injury to the respiratory tract or systemic toxicity (e.g. carbon monoxide poisoning).

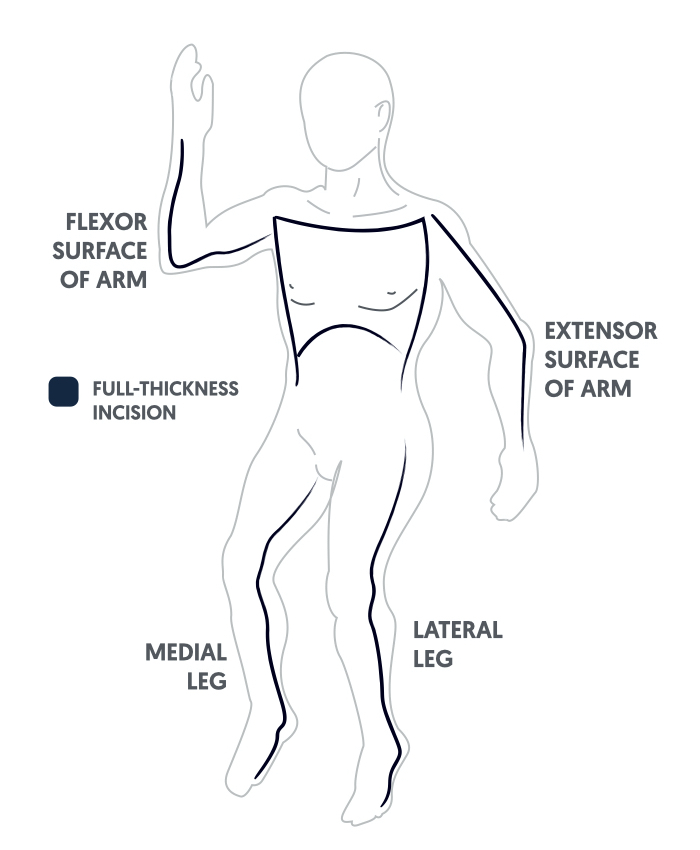

- Restrictive chest burns - circumferential or near-circumferential chest burns can severely restrict ventilation. If this is suspected, immediate escharotomy is indicated.

An escharotomy is an emergency procedure to incise burnt tissue in circumferential or near-circumferential deep-dermal or full-thickness burns in order to improve respiration and / or circulation to a limb.

C - Circulation

Check pulses and obtain intravenous (IV) access.

Bloods should be taken and IV fluid resuscitation initiated.

Limbs should be assessed to ensure they are adequately perfused. Circumferential or near-circumferential burns can severely restrict blood supply; with devitalised tissue acting as a tourniquet. Again, If this is suspected, immediate escharotomy is indicated.

D - Disability and neurological status

Assess patient’s consciousness with either AVPU or GCS, examine pupils and check blood glucose level.

Assess patient’s consciousness with either AVPU (alert, responsive to voice, pain or unresponsive) or using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Ensure pupils are equal and reactive, and check blood glucose level.

Beware that hypoxaemia and shock can cause restlessness and reduced GCS.

E - Exposure and environment

Fully expose the patient and examine head-to-toe.

Remove all jewellery, piercings and watches. Log roll the patient to examine the posterior surfaces. Assess burns and look for other injuries. Remember - patients with large burns lose heat rapidly, so cover and warm the patient as soon as the assessment is completed.

FATT

F - Fluid resuscitation

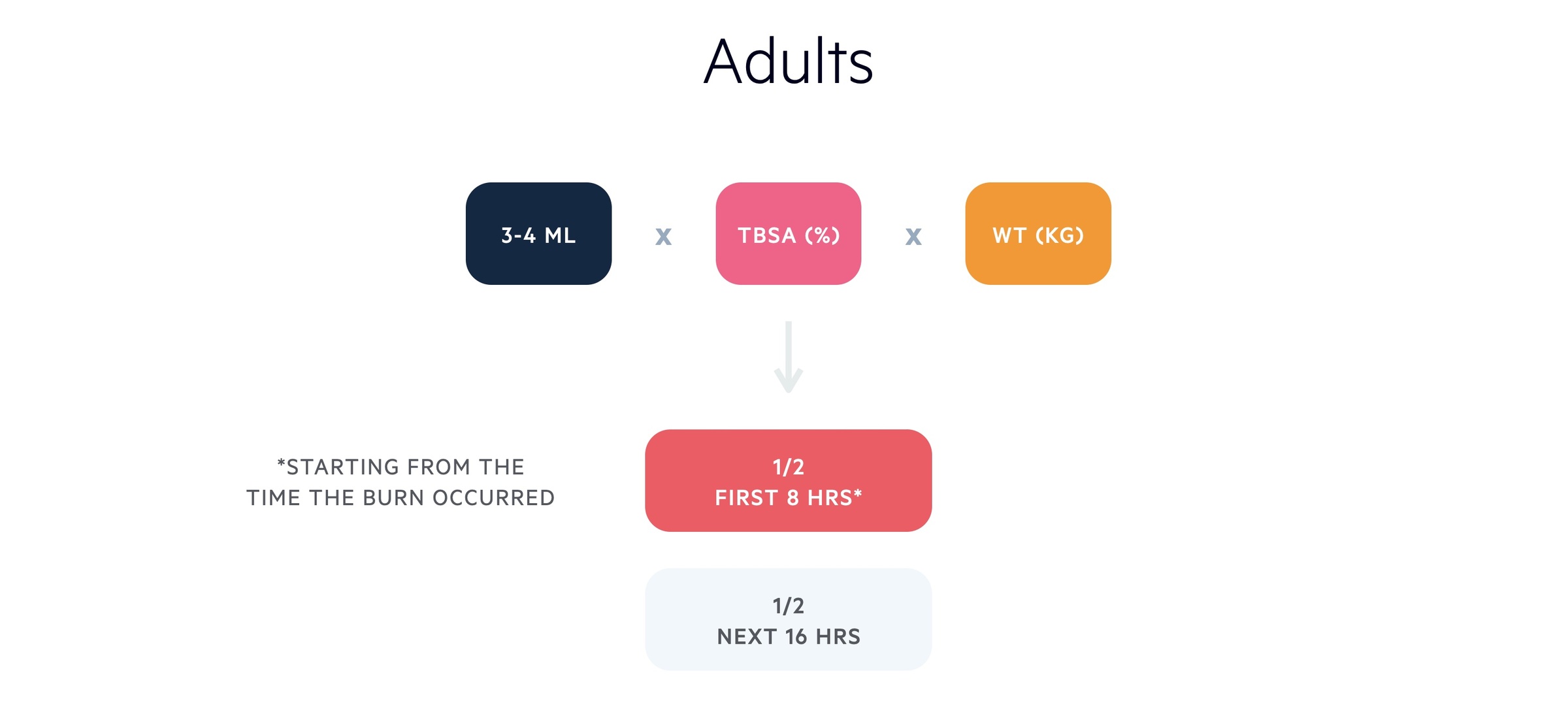

IV fluid resuscitation should be started in adult burns > 15% TBSA.

Patient’s should be resuscitated according to Parkland’s formula. Parkland’s formula takes into account the patients weight (Kg) and TBSA (%). Half of the total fluid calculated should be given in the first eight hours following the burn. The second half should be given in the subsequent 16 hours.

Remember - fluids should be calculated starting from the time the burn occurred and should take into account any fluid given enroute to hospital. For example, if presentation is delayed by three hours post burn, half the total amount is given over the remaining five hours.

The recommended fluid is Hartmann’s Solution.

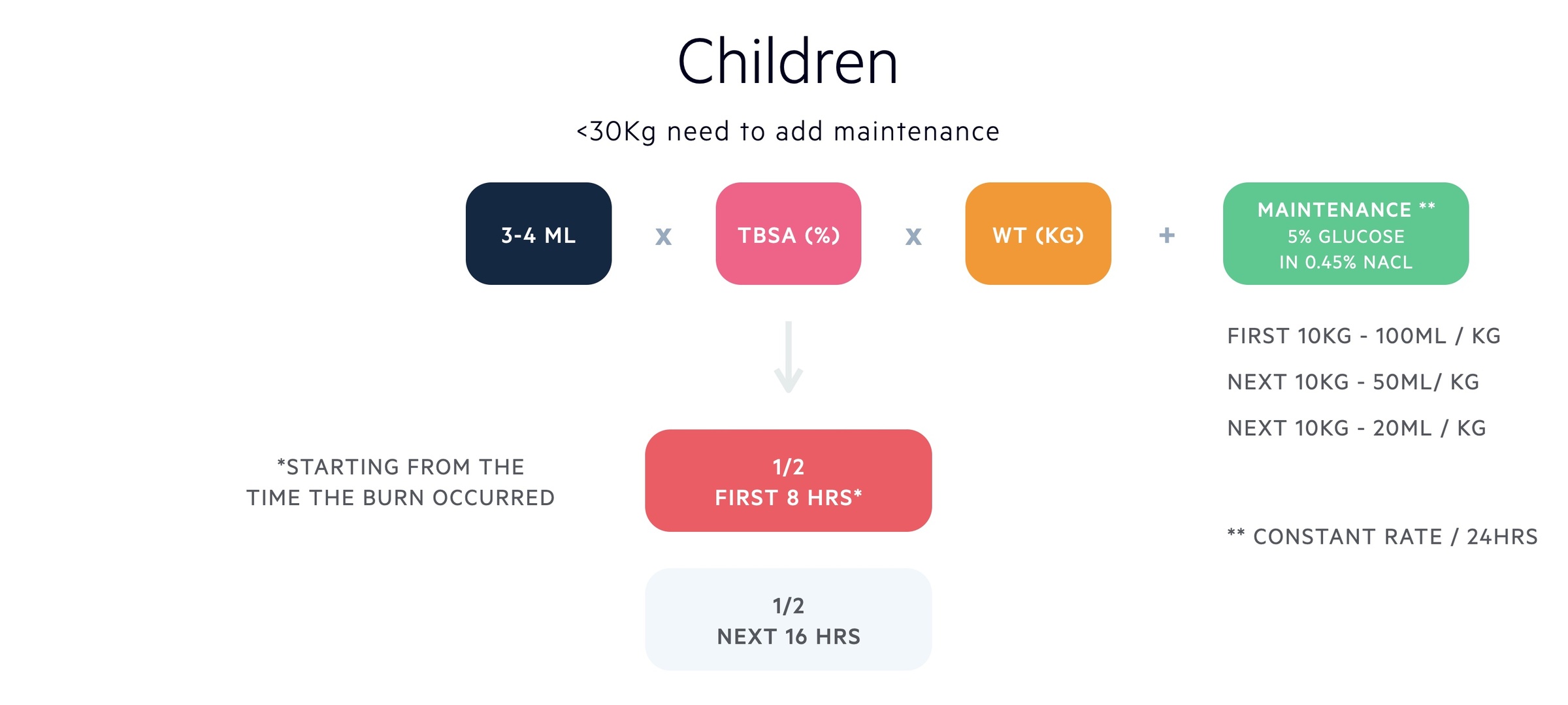

IV fluid resuscitation should be started in paediatric burns > 10% TBSA.

For children <30Kg, maintenance fluids need to be added. The recommended maintenance fluid is 5% glucose in 0.45% sodium chloride. Although some NHS trusts, particularly in Scotland, use human albumin solution (HAS). Maintenance fluid is given at a constant rate over 24 hours.

There are no level I or II publications to guide the choice of resuscitation fluid in either adults or children.

A - Analgaesia

Burns can be extremely painful. Appropriate analgaesia is paramount.

IV morphine (at a weight adjusted dose) should be administered to all patients with large burns and titrated against pain and respiratory depression. In children, intra-nasal diamorphine is also commonly used.

T - Tests

Investigations can be organised into bedside, bloods, imaging and special tests.

Bedside:

- Observations

- Blood pressure

- Urinalysis

- BM

- ECG (+/- monitored bed)

- Arterial blood gas (ABG)

Bloods:

- Full blood count (FBC)

- Urea & electrolytes (U&Es)

- Liver function tests (LFTs)

- Group & Save (G&S)

- Clotting screen

- Bone profile

- Creatine Kinase (CK)

- Cardiac enzymes

- Carboxyhaemoglobin

Imaging:

- Chest X-ray (CXR)

- Computed tomography (CT) - for example, a trauma CT may be indicated depending on the mechanism of burns (e.g. blast injury / electrocution with fall from height)

Special tests:

- Bronchoscopy

- Arterial line - invasive blood pressure monitoring

T - Tubes

An NG tube & urinary catheter should be placed in large burns (>20% TBSA in adults; >15% TBSA in children).

NG / NJ tube

Large burns have systemic effects, including immunosuppression and loss of normal gut barrier function. Gastric ileus is a potential complication and the stomach should be decompressed with the insertion of a nasogastric (NG) or nasojejunal (NJ) tube. Patients should be kept nil by mouth (NBM).

Urinary catheter

A Foley catheter should be placed to measure urine output.

Secondary survey

AMPLE history

- Allergies

- Medications

- Past medical history

- Last ate

- Events - mechanism of burn

Head-to-toe examination

Look for other injuries that may have been missed on the primary survey.

Tetanus

Burn sites are specifically susceptible to tetanus infection. Tetanus prophylaxis should be administered.

Documentation and Photography

Documentation should be meticulous and clinical photography should be performed. Photographs provide an objective description of the burn injuries at the time of admission.

Indications for referral to a specialised burns service:

- All burns ≥ 2% TBSA in children or ≥ 3% TBSA in adults

- All full-thickness burns

- All circumferential burns

- Any burn not healed in 2 weeks

- Any burn with suspicion of non-accidental injury (should be referred to burn unit / centre for assessment within 24 hours)

In addition, the following cases require discussion with a Burns Consultant:

- All burns to hands, feet, face, perineum or genitalia

- Any chemical, electrical or friction burn

- Any cold injury

- Any unwell / febrile child with a burn

- Any concerns regarding burn injuries and co-morbidities that may affect treatment or healing of the burn

Source: National Burn Care Referral Guidance, Feb 2012.

Last updated: November 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback