Renal colic

Notes

Introduction

Renal colic classically refers to acute severe loin pain that occurs secondary to a urinary stone.

Urinary stones, also termed urolithiasis, refer to stone formation anywhere within the urinary tract. They may be asymptomatic or cause acute loin-to-groin pain due to ureteric obstruction.

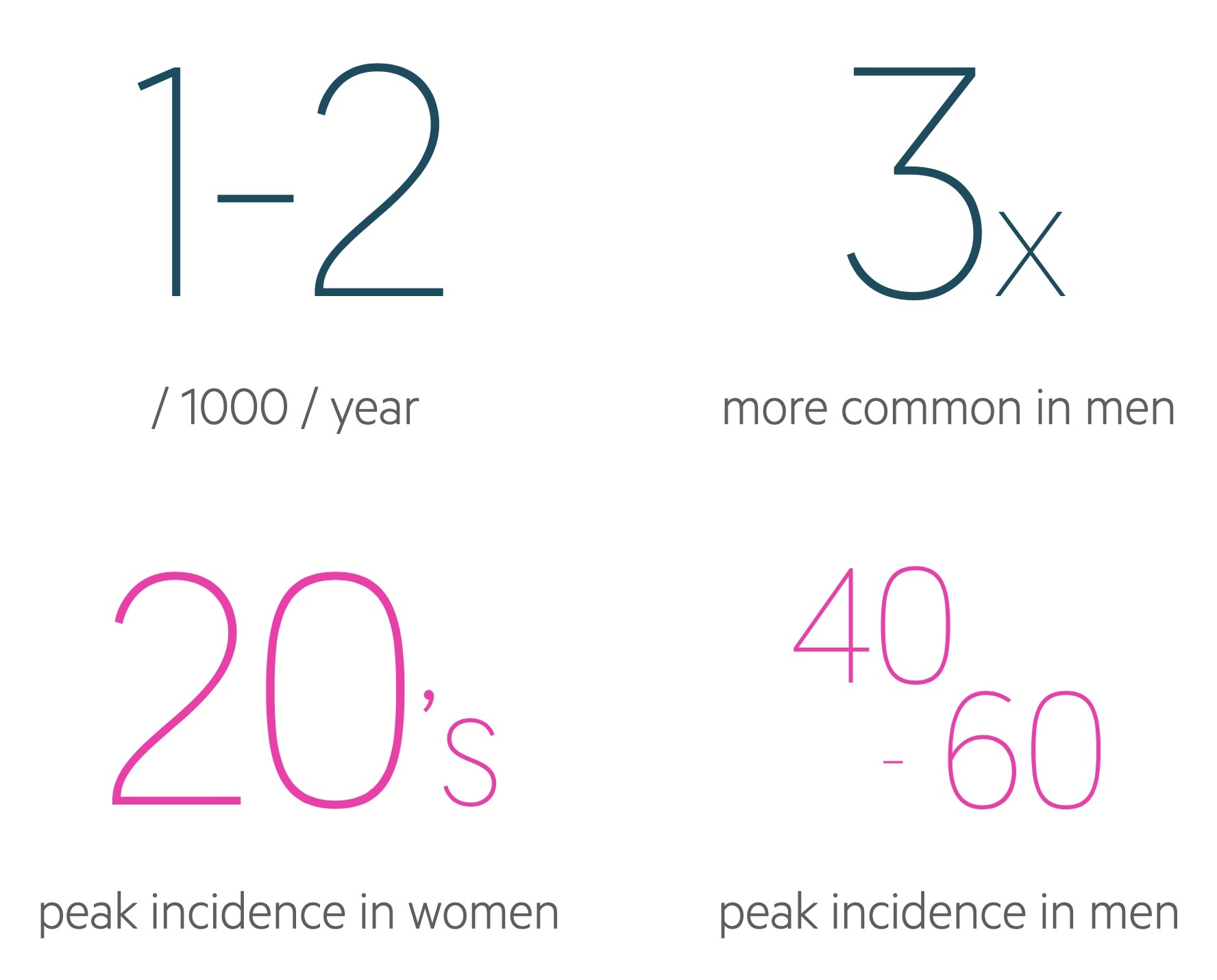

Urinary stones are extremely common, men are affected up to three times more than women. The peak incidence of symptomatic urinary stones is between 40-60 years in males and late 20’s in females.

Aetiology

Renal colic is caused by obstruction to urinary flow within the ureter that occurs secondary to urinary stones.

The majority of renal stones, approximately 80%, are composed of calcium. The most common being calcium oxalate, but calcium phosphate stones are also seen. Other types of stones include struvite (2-15%), uric acid (10%) and cystine (1-2%).

Calcium oxalate

Calcium oxalate is the most common type of stone and is thought to develop from the precipitation of calcium crystals within the interstitium. Accumulation of these crystals leads to the formation of ‘Randall's plaques’, which are subepithelial calcification of renal papillae. They are thought to act as a nidus for stone formation.

The development of calcium oxalate stones is associated with a number of factors. These include high concentrations of oxalate in the urine, loss of natural stone inhibitors (e.g. citrate, magnesium) and high urinary pH.

Struvite

Struvite stones are composed of magnesium, ammonium and phosphate. They may grow rapidly and can lead to the development of staghorn calculi - these are large stones that fill the entire intrarenal collecting system and cause renal dysfunction.

Struvite stones are associated with urease-producing microorganisms including Proteus and Klebsiella. These microorganisms are able to convert urea into ammonia which reacts with water increasing the pH of the urine. Collectively, the increased ammonia and alkaline urine promote stone formation.

Uric acid

The development of uric acid stones is strongly associated with a low urinary pH and a high urinary concentration of uric acid. The proportion of uric acid stones is higher in hot, dry climates because of the tendency to produce more acidic and low-volume urine.

Circumstances that increase the levels of uric acid predispose patients to the formation of uric acid stones. Classically, uric acid stones are seen in patients with gout who have hyperuricaemia and, therefore, hyperuricosuria. However, the likelihood of stone formation is still strongly related to urinary pH.

Cystine

Cystine is a homodimer of the amino acid cysteine. The development of cystine stones is usually secondary to the genetic disorder cystinuria in which there is impairment in the normal renal handling of cystine. This leads to failed reabsorption of cystine and precipitation within the renal tubules. Patients with cystinuria typically present with stones at a younger age.

Risk factors

A number of risk factors have been associated with stone formation.

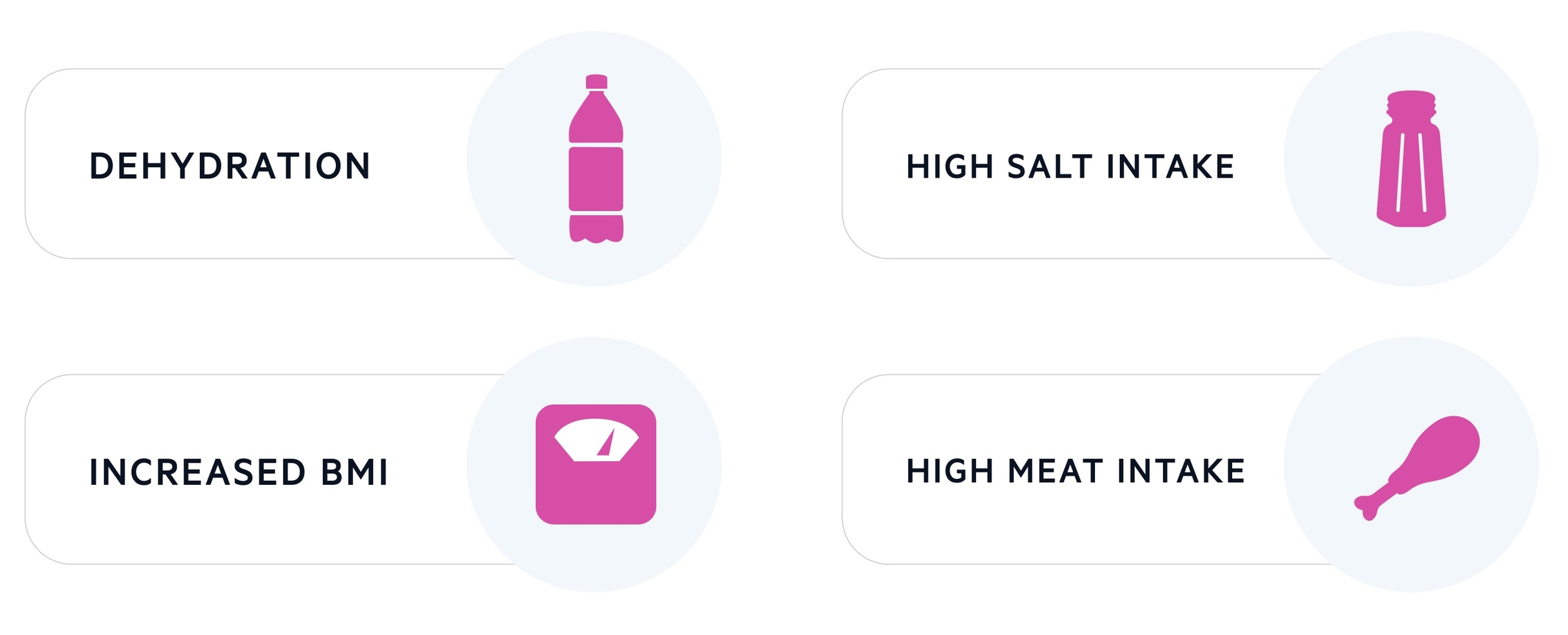

Modifiable

Modifiable risk factors are those that patients can change to help reduce the risk of calculi forming. Understanding these helps to form advice that can be given following the occurrence of a stone.

Certain medications may also be related to the development of renal calculi. These include protease inhibitors and diuretics - whether these can or cannot be adjusted depends on numerous factors.

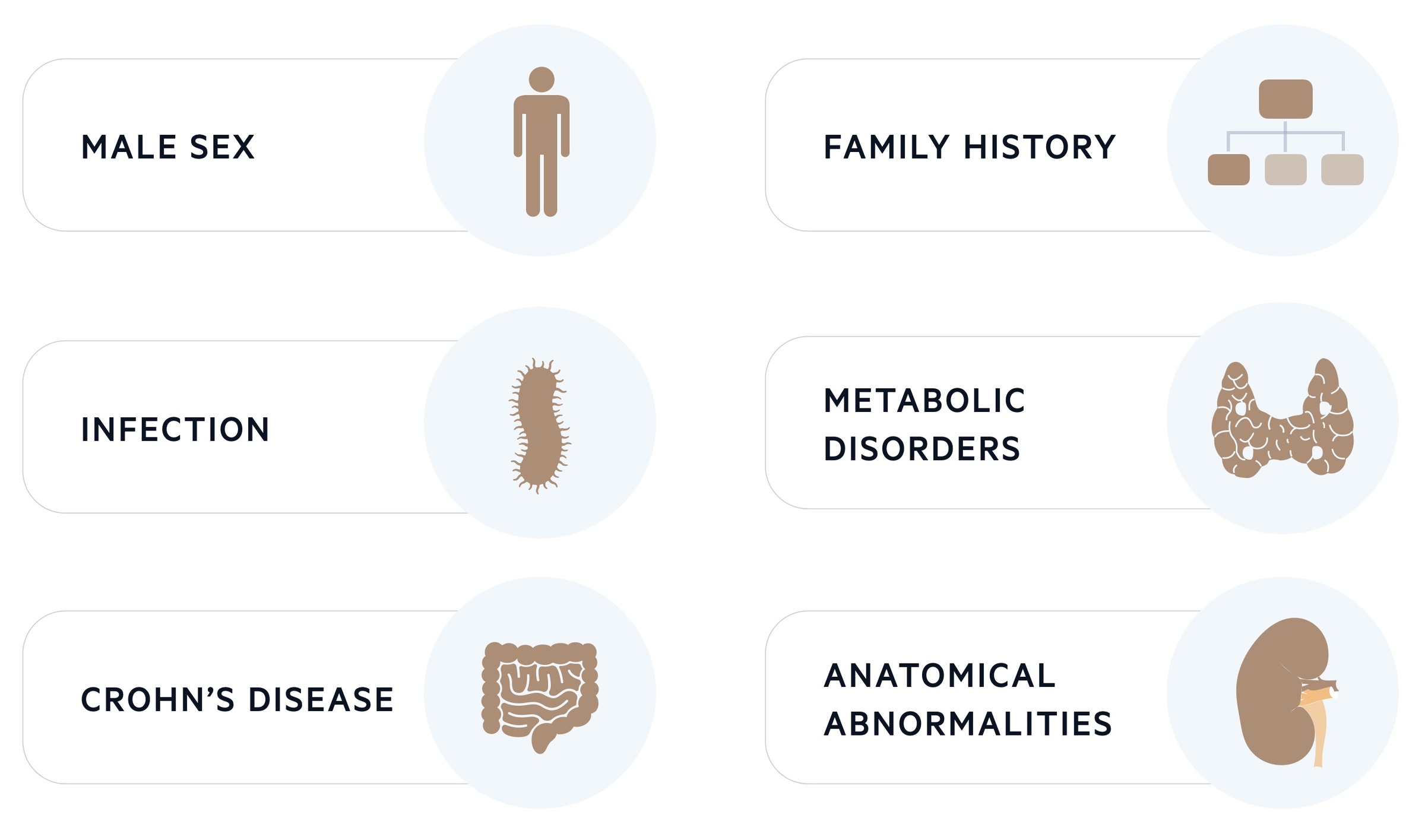

Non-modifiable risk factors

There are a number of factors that cannot be modified. Those with a family history of renal calculi, white ethnicity or male gender are at increased risk.

Pathophysiology

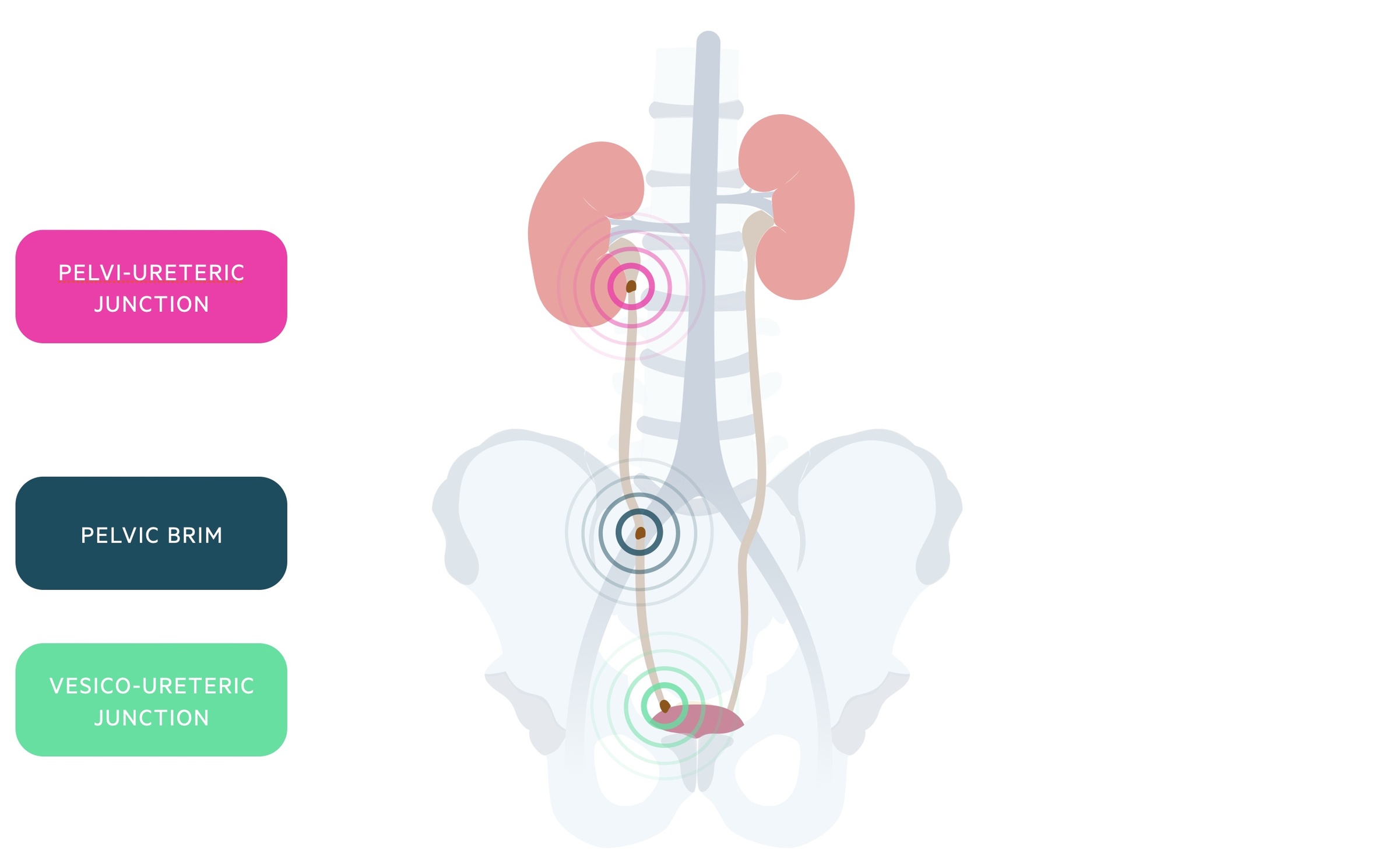

Urinary stones classically obstruct at one of three sites: the pelvi-ureteric junction (PUJ), the pelvic brim and the vesico-ureteric junction (VUJ).

The obstruction to flow within the ureter leads to the release of prostaglandins. Prostaglandins cause vasodilatation of surrounding vessels and stimulate ureteric smooth muscle spasm.

Blood vessel vasodilatation promotes a natural diuresis, which further places pressure on the kidney and can lead to distention of the renal capsule. Distention of this capsule causes the intense pain of renal colic, which is further exacerbated by ureteric smooth muscle spasm.

Renal colic occurs in paroxysms, 20-60 minutes long, that can be extremely intense. Renal colic pain usually settles quickly following relief of the obstruction (e.g. by a stent) or passage of the stone.

Clinical features

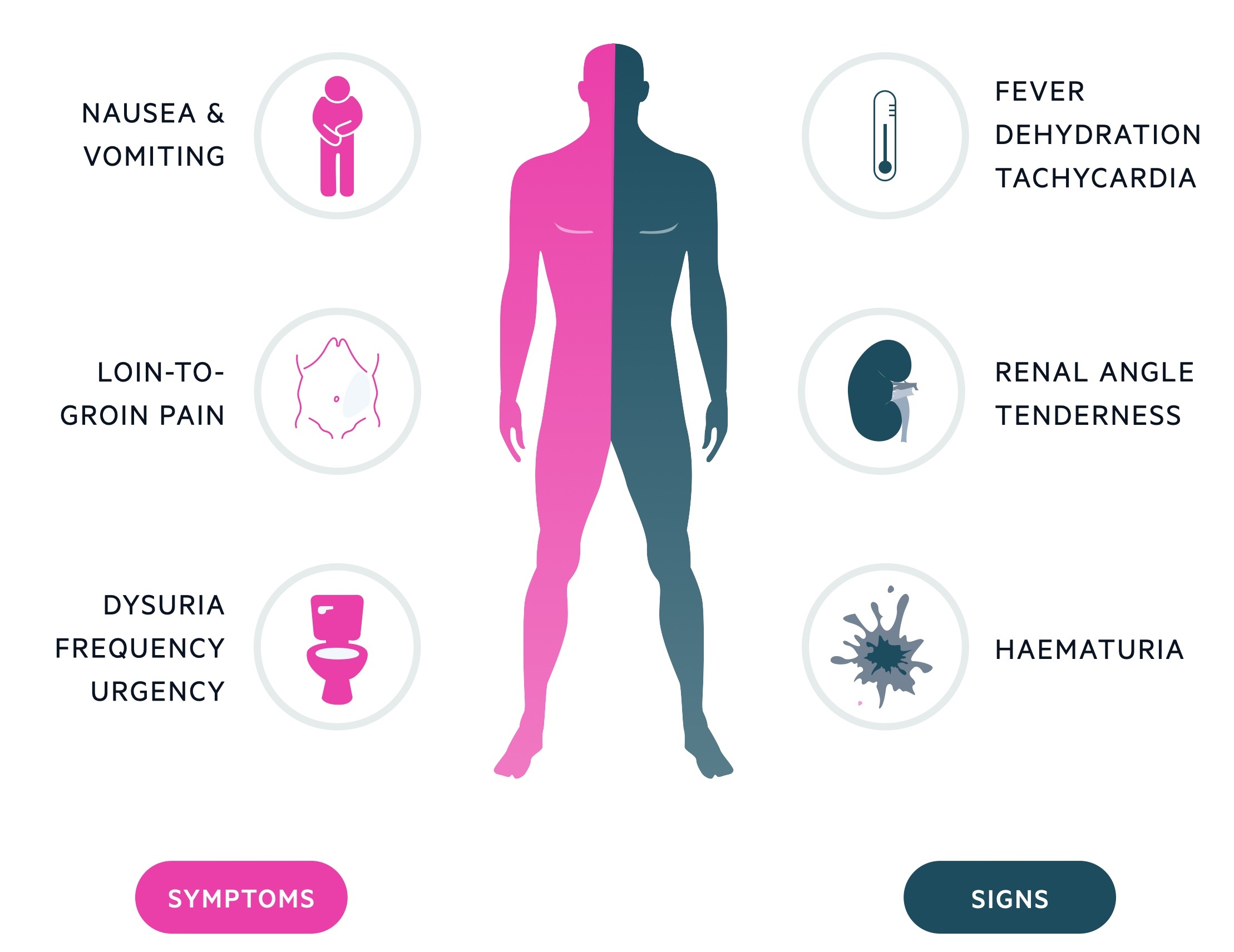

The classical presentation of renal colic is loin-to-groin pain.

The pain may occur in a colicky manner with waves of severe pain. Vomiting is common and normally associated with the pain.

Some patients may present with signs of infection - fever, tachycardia, malaise - and at times become frankly septic. An infected-obstructed urinary system is a urological emergency requiring urgent drainage.

Symptoms

- Loin-to-groin pain

- N&V

- Haematuria

- Dysuria

- Urgency

Signs

- Flank tenderness

- Haematuria (typically microscopic)

- Fever

- Rigors

It is important to monitor observations (e.g HR, BP, RR, Temp) and look for signs of infection as this could represent the development of urosepsis, which may require urgent urological management.

NOTE: It is always important to consider differentials such as an abdominal aorta aneurysm.

Diagnosis

The imaging of choice in the diagnosis of acute renal colic in non-pregnant adults is a non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan.

CT KUB

A CT KUB (kidneys-ureters-bladder) is a non-contrast scan that can be used to help identify both stones and urinary tract obstruction. It has a sensitivity in the high 90’s and has the benefit of being readily available and easily interpreted in a short space of time.

Importantly, non-contrast CT does not expose the patient to IV contrast which can be nephrotoxic. It is the first-line investigation in adult, non-pregnant, patients.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography tends to be reserved for patients where there is an increased risk of using ionising radiation. It is useful for the identification of hydronephrosis and may be used to look for stones and other gross abnormalities. It is the first-line investigation in:

- Pregnant women

- Children and young adults (i.e. people under 16 years)

Ultrasound is best suited for picking up large, proximal stones (e.g. > 5mm at the PUJ). It can be more difficult to visualise small, distal stones.

X-ray

Most urinary stones are composed of calcium which makes them radiopaque to plain radiograph. X-rays are inexpensive and typically quick to obtain. They are poor at picking up small stones and lack the sensitivity of CT KUB.

Although X-ray KUB’s have largely been superseded by non-contrast CT, they may play a role in the follow-up of radiopaque stones or to check stent placement.

A small number of stones (e.g. uric acid, indinavir-induced, cystine) are radiolucent and cannot be detected on X-ray.

NOTE: Interestingly, indinavir-induced renal calculi are not visualised on non-contrast CT and require the use of contrast-enhanced CT (i.e. CT urogram).

Investigations

Investigations are important for the basic workup of renal colic, assessment of complications and preparation for any surgical intervention.

Bedside

- Observations

- ECG

- Urinalysis (urine dipstick)

- Urine culture

Bloods

- FBC

- U&Es

- CRP

- LFTs

- Amylase

- Bone profile

- Uric acid

Imaging

See Diagnosis chapter.

Stone work-up

A metabolic stone workup can be completed in patients with significant stone disease. This involves:

- Stone analysis

- Serum calcium

Other tests may include uric acid levels and parathyroid hormone. Urinary collections may be arranged to look at oxalate, calcium, uric acid and citrate levels.

Management

In the majority of patients, renal colic can be managed conservatively with the use of analgesia and adequate hydration.

In general, the management of renal colic is dependent on the size and location of the stone. The larger (e.g. > 10mm) and more proximal (e.g. PUJ) the stone, the more likely intervention will be needed.

A stone that is < 4 mm in size will have an 80% chance of spontaneous passage whereas a stone > 8 mm in size only has a 20% chance of spontaneous passage.

In all patients, appropriate analgesia and hydration are important in the ongoing management. Urgent urological assessment should be considered in the following circumstances:

- Urosepsis

- Acute kidney injury/anuria

- Solitary functioning kidney

- Unresponsive pain

Analgesia & anti-emetics

NSAIDs are considered excellent for pain relief in renal colic as they help to reduce the ureteral spasm - particularly when given via the rectal route. They should be used with caution in patients with an AKI or with a history of gastritis or peptic ulcer disease.

Paracetamol may be given to aid or in place of NSAIDs whilst opioids are reserved for those whose pain is still uncontrolled.

Anti-emetics (e.g. ondansetron or cyclizine) can be used to help control nausea and vomiting.

Medical therapy

Medical expulsive therapy involves the use of medications, most commonly tamsulosin (an alpha-blocker) to help induce spontaneous passage of the stone.

This type of therapy can be considered in patients with small distal stones, controlled symptoms and no evidence of sepsis.

Patient's should receive follow-up in 'stone clinic' and be appropriately counselled on signs of potential complications.

NOTE: The SUSPEND trial found tamsulosin did not reduce the proportion of patients requiring further treatment for stone clearance at four weeks. It remains however an area of debate with some clinicians continuing to prescribe tamsulosin, pointing to studies indicative of benefit for stones 5-10mm in size.

Surgical/radiological interventions

Definitive management of urinary stones depends on the size of the stone, site of obstruction and the clinical presentation. It is normally required for ongoing pain associated with stones unlikely to pass naturally.

Therapeutic options for the management of urolithiasis include:

- Shockwave lithotripsy (SWL): a non-invasive procedure that uses shockwaves to break up stones. Normally indicated in those with stones less than 20mm in size.

- Ureteroscopy (URS) with laser lithotripsy: a urological procedure where energy devices are used to break up the stones, normally indicated in stones 10-20mm in size or less than 10mm where SWL fails or is contraindicated.

- Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL): a nephroscope is passed into the collecting system and used to break up stones. Tends to be reserved for larger stones (> 20mm) or in smaller stones where other measures have failed.

Patients who have uncontrolled symptoms or develop complications (e.g. urosepsis, AKI) may require initial relief of obstruction before more definite interventions can take place. The two main options for relieving obstruction include radiologically-guided insertion of a nephrostomy tube into the renal pelvis under local anaesthetic or insertion of a ureteric JJ stent under general anaesthetic.

Prevention

Measures may be taken to help prevent and reduce the risk of recurrence of renal calculi.

NICE CG 118 (2019 update) outlines measures that can be used in the prevention of calculi. These are summarised below.

Address modifiable risk factors

There are a number of changes patients can make (where relevant and appropriate) that can help to reduce the chance of recurrence:

- Avoiding excess salt

- Good oral hydration (and adding lemon juice to drinking water)

- Avoiding carbonated drinks

- A balanced diet

- Healthy weight loss

Potassium citrate

In addition to the above advice potassium citrate may be given to:

- Adults: with recurrent stones that are > 50% calcium oxalate.

- Children and young people: with recurrent stones that are > 50% calcium oxalate with either hypercalciuria or hypocitraturia.

Citrate acts as an inhibitor of crystallisation of calcium salts - hypocitraturia has been shown to be a risk factor for the development of calcium oxalate stones.

Thiazides

In addition to the advice regarding modifiable risk factors, thiazide diuretics may be given to adults with:

- Recurrence and

- Stones that are > 50% calcium oxalate and

- Hypercalciuria after

- Restricting salt intake to 6g / day

Thiazides are relatively inexpensive and reduce urinary calcium, reducing the risk of calcium-based stones.

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback