Acute limb ischaemia

Notes

Overview

Acute limb ischaemia (ALI) refers to a sudden decrease in blood supply resulting in ischaemic injury to the lower limbs.

ALI is caused by sudden obstruction to arterial flow (venous obstruction can cause ALI but is rare) most commonly secondary to embolism or thrombosis. In the setting of complete ischaemia, necrosis results after around 6 hours.

Non-viable limbs mandate amputation in around 10-15% of cases and the condition is associated with a high mortality of approximately 15-20% within one year of presentation. This mortality is related both to the condition itself and the age and co-morbid status of the patient group in which it most commonly occurs.

Smoking, diabetes and advancing age are all key risk factors. Treatment involves analgesia, heparin and revascularisation (e.g. thrombolysis, thrombectomy, bypass).

Aetiology

Acute limb ischaemia is most commonly caused by embolisation or thrombosis.

Thrombosis

Arterial thrombosis is a common cause of ALI. This normally occurs in a vessel with pre-existing atherosclerosis. The rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque occurs when the cap breaks off exposing a rough and thrombogenic surface resulting in further relatively rapid thrombus progression.

Thrombosis also commonly affects the walls of aneurysms due to the turbulent local flow. This is seen in popliteal artery (found at the back of the knee, a continuation of the superficial femoral artery) aneurysms. Thrombosis from these aneurysms can also break off as embolic bodies and cause distal blockages. Patients may also be predisposed to thrombosis due to inherited or acquired hypercoagulability.

Embolism

Embolisation refers to a solid deposit (typically a piece of thrombus) traveling from its source (typically central) and lodging in a distal vessel. This often occurs from a cardiac source of thrombus (e.g. secondary to AF or an MI) or one associated with a proximal aneurysm (e.g. AAA, popliteal).

Paradoxical embolisation refers to emboli from the venous circulation that cause arterial obstruction. They are termed 'paradoxical' as theoretically they should not occur, any venous embolism should travel to the heart before becoming lodged in the pulmonary circulation. However, in patients with cardiac defects (e.g. atrial septal defect), emboli can pass directly from the right side of the heart to the left. They commonly cause strokes but can also cause ALI.

Other

- Acute aortic dissection: can result in impaired blood supply to the limbs (as well as the rest of the body).

- Trauma: a traumatic arterial injury can impair blood supply.

- Phlegmasia cerulea dolen: a rare complication of a DVT in which venous congestion results in oedema and impaired blood supply to tissue.

Risk factors

Smoking and diabetes are the two most significant risk factors for developing PAD.

- Smoking

- Diabetes

- Age

- Hypertension

- Hyperlipidaemia

- Obesity

Clinical features

Classically the 6 P’s are used to describe the features of acute limb ischaemia.

In embolic disease, onset is sudden and the limb is more likely to be ‘white’ with a complete lack of peripheral blood flow beyond the point where the embolism settled. There is no time for collaterals (vessels that offer an alternative route for blood, they can develop due to narrowed or blocked vessels prompting new vessels to form) to have developed (collaterals may be present in patients with pre-existing arterial disease).

Where ischaemia occurs due to thrombosis, onset may be more gradual and collateral supply may have developed secondary to pre-exiting disease. They often present with acute worsening of underlying vascular disease.

The six P’s of acute limb ischaemia are:

- Pain

- Pulseless

- Pallor

- Paralysis

- Paraesthesia

- Perishingly cold

Most texts refer to pallor as a pale or white appearance. This will however appear differently depending on the patient's skin tone. It is important to note overall black individuals appear to be at an increased risk of limb ischaemia. Changes may be subtle or less apparent and as such a higher index of suspicion should be held.

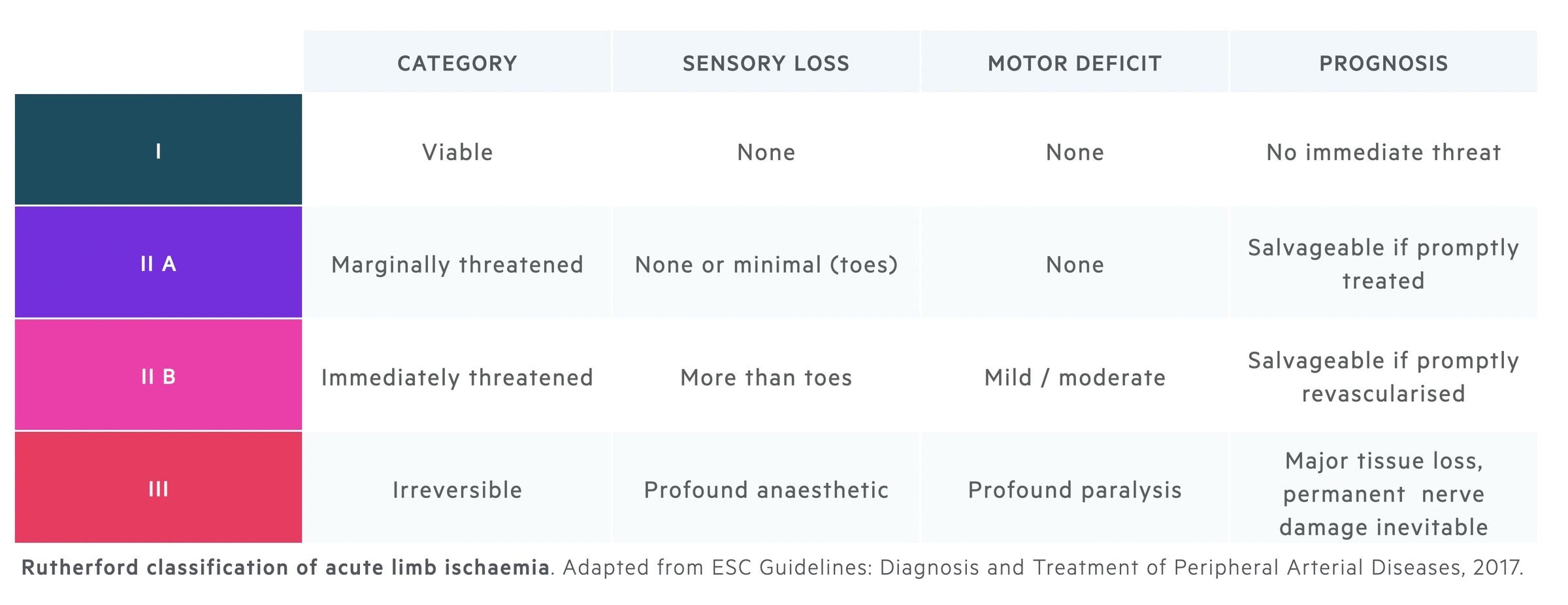

Rutherford classification

The Rutherford classification can be used to grade and guide management in acute limb ischaemia.

Investigations

Diagnostic imaging can be non-invasive (e.g. US, CT) or invasive (e.g. DSA).

Bedside

- Observations

- ECG (in particular lookout for arrhythmias like AF)

- BM (blood sugar)

Bloods

- FBC

- U&Es

- LFTs

- Clotting screen

- Group and save

- VBG/ABG (obtain a lactate measurement)

- Consider a thrombophilia screen

Imaging

Duplex ultrasound (DUS): a non-invasive technique that allows visualisation of the arteries and assessment of stenosis.

CT angiogram (CTA): a non-invasive technique that uses IV contrast to allow visualisation of the arteries and any narrowing/occlusion.

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA): an invasive technique that utilises catheter-guided contrast injection (into the vessel of interest) combined with fluoroscopy (a form X-ray imaging in which multiple pictures are taken over a short period of time). Digital subtraction removes the background image to isolate the contrast and vessels.

Other imaging may be obtained to identify the underlying cause of the ALI. An echocardiogram is helpful if a cardiac origin of embolism is suspected. This is not as urgent as other diagnostic imaging or revascularisation but can occur following appropriate treatment.

Management

The rate of amputation is linked to ‘time to reperfusion’, as such prompt recognition and management are key.

A variety of treatment modalities are available and choice should be guided by experienced specialists. The choice depends on the presentation, with the presence of a neurological deficit of particular importance.

Initial management involves symptomatic relief (analgesia for the pain) and heparin (an anticoagulant). Heparin improves patients symptoms and is thought to prevent proximal or distal propagation of thrombus.

Following this revascularisation is required - this refers to restoring adequate blood supply to the ischaemic tissue. The general treatment options and terms to be aware of are:

- Intra-arterial catheter thrombolysis: a percutaneous technique that involves obtaining vascular access with a catheter and injecting a thrombolytic (clot-busting) agent directly into the affected vessel. Alteplase is a commonly used agent. This is generally suitable for less severe cases without neurological deficit.

- Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy/thrombo-aspiration: these are percutaneous techniques that allow for the removal of the thrombus. They can be combined with catheter-directed thrombolysis.

- Surgical thrombectomy: open surgical techniques are still commonly required. One option is surgical thrombectomy in which the vessel is opened and thrombus removed.

- Surgical bypass: bypass involves placing a graft connecting the vessel proximal to the obstruction to the vessel distal to it.

Management is complex, here an outline of possible management options is shown. They are adapted from ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, 2017.

- Initial management: once recognised, if not at a specialist centre, you must liaise with and discuss transfer to your local vascular centre. Initial management typically consists of analgesia and heparin. Heparin is an anticoagulant that potentiates the action of antithrombin III.

- Rutherford I: there is generally time to arrange imaging workup (e.g. CTA, DUS). Revascularisation can be attempted with catheter-directed thrombolysis, thrombectomy or bypass.

- Rutherford II: urgent revascularisation is indicated and imaging should not delay this. It is typically achieved with a thrombectomy or bypass. If an underlying vascular lesion is present endovascular therapy or surgery should be attempted.

- Rutherford III: irreversible damage with dead, non-viable tissue mandates amputation of affected areas.

In some patients, surgical or percutaneous intervention can be felt to be inappropriate due to patient wishes or their co-morbid status. In these cases symptomatic relief and conservative measures (e.g. consider ongoing heparin infusion) should be implemented and palliative care input sought.

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback